Читать книгу Canaletto - Octave Uzanne - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Venice during the Eighteenth Century

Il Carnavale

ОглавлениеOver a period of six months, the carnival attracted throngs of close to thirty thousand foreigners to Venice. Its theme: down with serious matters, long live freedom and folly! Yokels and patricians alike seemed to be overtaken by the same vertiginous activities, consumed by parades of people dressed up as astrologers, doctors, lawyers and gondoliers. Among the clowns, who wore huge cone-shaped hats, the most nimble of the bunch advanced on their hands, others danced about while playing barrel organs and the whole group whirled about to the sound of lively music. The people, free to loudly express their condemnation or approval, followed each group with shouts, catcalls, applause and jeers. At Saint Mark’s Square, the major neighbourhood for masks, one wandered about without advancing through the dense crowd. The seven theatres reserved for the carnival proving to be inadequate for the festivities, harlequins performed their tomfoolery in the open air and comedic improvisers amused spectators with their buffoonery. At the smaller intersections, feats of strength and sleight of hand were organized. At the end of the carnival, there remained nothing but a few scattered passers-by appropriately armed with axes and cutlasses to defend themselves against the bulls that were led through the streets, fighting in certain places.

On Fat Thursday, the butchers’ festival, a bull was beheaded with a single blow of the sword, a barbaric amusement established to commemorate an old victory over the Patriarch of Aquileia. The latter, accompanied by twelve clergymen captured at the same time, was to be beheaded in Saint Mark’s Square, but, for some reason, this public execution did not take place, and twelve pigs and a bull were substituted for the condemned in order to appease the public. That same Thursday, the doge watched the Strengths of Hercules,[2] a game consisting of the construction of a human pyramid with a base of eight men locked arm in arm and capped with a child. In addition, an acrobat equipped with wings glided down a rope stretched between the top of the bell tower and the Doges’ Palace balcony. Taking this aerial route, he arrived in front of the doge, offered him compliments and flowers, and then showered poetry and sonnets upon the crowd, enjoyed even by the least literate. A war of fists was another gift of lively amusement for the spectators. In this bizarre jousting match, two sides advanced atop a narrow bridge with no parapet, namely the Saint Barnabas bridge, and each forced his way through, knocking his adversaries into the water. Seeing the fighters fall like grapes into the water, the spectators beat their hands together as wildly as possible.

The whole of Venice was consumed in this rejoicing, in the enthusiasm of the crowd, in this emulation of which paintings and engravings give us a rather sketchy idea, in the joyful stamping of feet and cheering for the conqueror, in the freedom reigning sovereign over the city, encouraged by the incognito mask that, for the moment, suppressed all decorum and social inequality! The mask was a constant custom in Venetian mores. A mask was required to enter the gaming rooms, or ridotti, densely crowded with men and women. It was not unusual to see costumed nobles walk into the Doges’ Palace, removing their domino in the Grand Council’s antechamber. No one considered it scandalous to run into masked visitors in convent reception rooms or at gala dinners where the doge would bestow purple robes on the magistrates. Once promised in marriage, a young noblewoman might conceal her features under a velvet hood, and no one would see her face uncovered except for her fiancé and those privileged people to whom this rare favour was accorded.

9. The Grand Canal in the Vicinity of Santa Maria della Carita, 1726.

Oil on canvas, 90 × 132 cm.

Private Collection.

Though these young women lived like prisoners inside palaces with barred windows, somewhat like Oriental women, occupying themselves with embroidery and making the marvellous lace on which Venice prided itself, they were suddenly emancipated through marriage and never again knew such crippling restraints on their freedom to be alluring. Those whose behaviour remained irreproachable drew from their devotion a self-restraint imposed neither by a family-oriented mindset nor the opinion of a libertine society. Since marriage was considered a formality importing little gravity, this forgetting of all duty led naturally to an abandonment of family life. They would spend the entire day out in the open air. Casinos served as a rendezvous point. There was something for the ladies, as well as for their husbands. Their children were like pretty dolls, dressed in rich outfits and prepared with good manners. As for the adolescents, they shocked travellers with the rowdiness that Venetians found amusing.

Discipline having lost its authority in schools, total capriciousness reigned in education. That of the writer Goldoni can serve as an example. In Rimini, bored with philosophical subtleties and passionate about ancient clowns and the theatre, he found a troupe of comedians made up almost entirely of his own countrymen. Under the pretext of going to Chioggia to kiss and greet his mother, he boarded their gondola and embarked on their journey. After that jaunt, having received a scholarship to a theological school in Pavia, he took up wearing the cloth with other worldly and stylish young abbots. But instead of applying himself to canon or civil law, he concentrated on fencing and the pleasurable arts, that is to say, all the games of society that a perfect gentleman could not ignore. Nevertheless, this life of extravagance did not prevent him, when in Chioggia, from composing a sermon that conferred on him a reputation for eloquence.

As far as convents were concerned, the cloister did not prove to be an adequate barrier between the recluses and the outside world. One of Longhi’s most interesting canvases at the Correr Museum is precisely a representation of a visit by patricians to a nunnery. The impression is entirely profane. Through the barred windows, the nuns and boarders appear to lend a self-satisfied ear to the sounds from outside. For the amusement of this attractive company, whose cuffs and garments bear typically Venetian floral embroidery, a small stage has been set up in a corner, while a beggar asks alms from a group of noble lords.

10. Capriccio: the Rialto Bridge and the Church of San Giorgio Maggiore, c. 1750.

Oil on canvas, 167.6 × 114.3 cm.

The North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh.

11. The Rialto Bridge from the South-west, c. 1740–1745.

Pencil and ink, 26.6 × 36.7 cm.

The Royal Collection, London.

12. The Grand Canal and the Rialto Bridge, looking from the South, c. 1727.

Oil on copperplate, 45.5 × 62.5 cm.

Private Collection.

13. Molo and Riva degli Schiavoni, c. 1727.

Oil on copperplate, 43 × 58.5 cm.

Private Collection.

Hardly interested in mysticism, the Venetians loved the ecstasy of religious ceremonies, the processions dazzling with priestly ornamentations, the golden dais, the unfurled banners, the doge and the patriarch, the throng of clergymen, and the six companies from the Scuole Grande.[3] For them, religion was equivalent to patriotism. Hadn’t Saint Mark’s body, which was spirited away from Alexandria, become a holy relic, a kind of Palladium? Just as the people shouted, “Siamo Venzian! e poi cristiani” (Venetian first, then Christian!), the clergy itself did not always kindly receive instructions from the Holy See. Moreover, men of the cloth had been overtaken by mistrust for the government. From the moment that a man enjoyed any benefit from the Church, be it a diploma or priesthood, he was immediately excluded from any public office and debarred from any positions he could have held. Likewise, every minister of the Republic was prohibited from appealing to the pope for a red hat, or for any prelacy.

The Inquisition still existed in Venice during the eighteenth century, but the Roman legal representatives never resembled the sinister delegates of Philip II in Spain. Moreover, three lay nobles, designated by the Senate, who had the power to annul any sentence handed down by the Holy Office, were assistants to ecclesiastical advisers. More fearsome in name than in act, this tribunal limited itself to a right to censorship only in relation to literary and artistic works. It was under this authority that Veronese was summoned to explain the presence of useless characters and improper details in his religious paintings. He used the following defence: “All of us painters are something akin to madmen and poets, acting according to the fancy and whims of our imaginations”. For his nominal “sentence”, he was forced to incorporate certain changes to the vast compositions he had painted for the refectory of the convent of Saint John and Saint Paul. One can easily foresee just how much this law of censure had become illusory during Canaletto’s time.

Trade relations brought Jews, Greeks, Muslims, and, later, Reformists, into the Piazza. The majority of European nations had a neighbourhood and a consul in Venice. For example, Jews and Greeks were stationed north of the city. However, while the Venetians wisely employed a freedom of belief in their hospitality, they rejected any doctrines. Thus, neither Luther nor Calvin counted a single one of Saint Mark’s children among their new followers. However, certain Epicurean theories, which had newly been brought to light through Cesare Cremonini’s brilliant commentaries, found more credit with them. This famous interpreter of the philosophers of Antiquity at Padua University had no fear of teaching that the soul was transmissible like the body, and thus was not immortal. Many nobles, having accepted this materialist and atheistic system, applied its conclusions to their lives. In this way, a veritable paganism was introduced not only into minds, but also into mores. This total absence of scruples had already appeared two centuries before in the influence that Aretino enjoyed. Was not his insolent pretence of posing as the arbiter of destinies tolerated? Showered with pensions and gold chains from nobles, he lived like a great lord among his contemporaries who flattered him and shuddered to see his stairs sullied by the feet of visitors who came to hear and admire him.

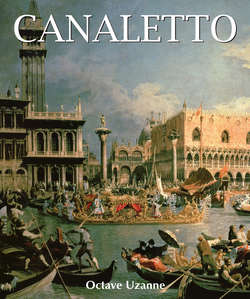

14. The Bucintoro returning to the Molo.

Oil on canvas. The Bowes Museum,

Barnard Castle.

15. A Regatta on the Grand Canal, c. 1733–1734.

Oil on canvas, 77.2 × 125.7 cm.

The Royal Collection, London.

2

See Guardi’s painting in the Louvre.

3

See Guardi’s painting in the Louvre that depicts the Corpus Christi procession at Saint Mark’s Square.