Читать книгу Canaletto - Octave Uzanne - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Venice during the Eighteenth Century

The Nobility

ОглавлениеThese patricians, however, jealously guarded the secret to their nobility, the oldest in all of Europe. Certain families could still boastfully count among their ancestors those who had elected the first doge in the seventh century. One of his successors, Gradenigo, attained a truly revolutionary success for the aristocracy by abolishing, in 1297, the custom of annually renewing the Grand Council. He then declared as irremovable all those who had been a part of the Council for four years and granted the male descendents the right to sit in the same role as their fathers. This was the origin of the famous libro d’oro,[4] in which the names of permanently noble families appeared. Failure to register meant the forfeit of nobility. Plebeians and foreigners could likewise be registered after they proved, through their actions, their allegiance to the State. Following the Chioggia War (1378–1381), thirty families in the nation were given noble status in this way. The registry was then reopened in 1775 to remedy the impoverishment of an entire caste, adding commoners who had the most assets.

However, this oligarchy was rather mismanaged by the government, whose behaviour caused fewer problems for the general population. The doge himself was closely watched. The example of his predecessors, many of whom had died a violent death, and the tragic stories about the Foscaris and the Marino Falieros, even more so than the shape of the corno ducal, which was quite similar to a Phyrgian cap, reminded him that he was nothing more than the Republic’s first subject. Always fearful of conspiracies, the government intervened in the private affairs of the nobles, prohibiting any involvement with representatives of foreign powers. This way it could prevent large fortunes from accumulating within the same household. Was not a patrician executed for having done nothing more than going on a mission without telling anyone about it? Was not one of the Pisanis, in the middle of the eighteenth century, who had inherited 150,000 ducats, forced to give up the man she had chosen for marriage because he was too wealthy and to give her hand to a suitor with no fortune? Likewise, the patricians, who were forever being thwarted by sumptuary laws, were not permitted to wear, except on holidays and carnival days, any gems or colourful outfits after their novitiate, that is to say, after the first two years of their marriage.

Noble pride, and an awareness of its vitality, which had made the nation so powerful during the “grand age”, no longer survived. Mores, as they weakened, became imbued with sentimentality and people delighted in taking part in petty intrigues or issues of etiquette. To use only the third person was considered polite and the art of bowing was very complicated: one had to make them very low even though one might not be aware of whether or not “a good half foot of one’s wig was dragging on the ground”. And what’s more, lords had been seen punishing passers-by who had not shown them enough respect by pushing them into the lagoons. The most humble way of submitting a request was to go to Broglio, where high-ranking citizens gathered every day, and kiss the sleeve of one’s protector. Whenever a patrician was promoted, there were never-ending compliments and congratulations that seemed almost comical. Charles de Brosses, witnessing the election of a general for the galleys, was amused by the prostrations of the new official and the maternal kisses lavished upon him as he exited the Grand Council: “They rang the bell so that they could be heard in the middle of the square”. The practices of courtesy at this time were truly exquisite, even on the part of the courtesans, and the general character had become quite peaceable. De Brosses affirmed that “Venetian blood is so sweet that, despite the ease given by masks, the allures of the night, the narrow streets and especially the bridges without guard rails, from which one can push an unsuspecting man into the sea without worry, there are less than four such accidents each year, even those arrive only amongst foreigners”.

16. The Bacino looking West on Ascension Day, c. 1734.

Pencil and dark ink, 27 × 37.5 cm.

The Royal Collection, London.

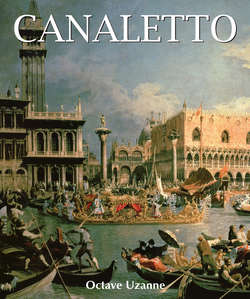

17. The Bacino di San Marco on Ascension Day, c. 1733–1734.

Oil on canvas, 76.8 × 125.4 cm.

The Royal Collection, London.

Nobles lived in places like the Grimani, Pesaro, Vendramin, Loredano and Pisani palaces, which, for the most part, were situated along the Grand Canal. These splendid dwellings where true treasures of art had often been accumulated were often no less impractical than they were sumptuous. At the Labais Palace, the lady of the house showed Charles de Brosses four pieces of jewellery made with emeralds, sapphires, pearls and diamonds that were truly of royal luxury, but with which she could not adorn herself. The Foscari Palace, from which there was a unique view, and which sheltered Henry III, was famous for its magnificence. It contained two hundred luxuriously furnished rooms that were decorated with priceless paintings. On the other hand, de Brosses found there neither any corner “nor any armchair where one can sit down and chat, because of the fragility of the sculptures”. Moreover, many of these impressive and ornamented exteriors served to hide veritable miseries, such as when the entire Gozzi family occupied the house together. While his father was paralyzed, Gaspard, the oldest of the children, with a pensive and misdirected character, remained lost in his literary endeavours. Neglecting his household responsibilities, he left all power in this domain to his wife, the famous Luisa Bergalli, who depleted the family fortune and nearly caused them to sell the palace. Upon the death of their grandfather, and after six years of discussion among his children, it was necessary to take a loan in order to give him a decent funeral. For many, negligence went hand in hand with levity: some fled stressful matters by travelling, others lived shamelessly at the expense of café owners, and still others were completely idle, spending most of the day in bed. It was not easy for foreigners to penetrate palaces and be welcome at events hosted by patricians, who preferred to discuss their conspiracies and intrigues free from the presence of outsiders. The adviser de Brosses related the following: “My good nobles are all coming to the café this evening, where they will talk with us in the spirit of good friendship. But for us to enter their homes, that’s another matter. As far as that’s concerned, there are not all that many homes that host gatherings in Venice, and these gatherings are neither numerous nor entertaining for foreigners. One cannot even turn to the refuge of a game of cards, for one must be a wizard to understand their cards, which have neither the same name nor the same pictures as ours. The Venetians, in spite of all their prosperity and palaces, will not even serve a roast chicken to their guests. I went several times for conversation to the home of a procuress named Foscarini, a very friendly woman with an immensely rich mansion. Despite the luxury, around three o’clock, which would be eleven o’clock at night in France, twenty valets brought in, on a large silver platter, an enormous pumpkin that they call a watermelon cut into quarters, a detestable alimentation if there ever were one. A pile of silver plates came along with it. Each of us pounced on a piece, afterwards washed it down with a small cup of coffee and finally returned home at midnight for dinner, with a clear head and a hollow stomach”.

That is what Venetians, whom the inhabitants of Florence describe as grossolani (uncouth), were like. As far as our traveller was concerned, he appreciated the Canary and Burgundy wines of Marshal Schulembourg and the feasts where ambassadors pampered him, especially one from Naples, “the most frank of fools one could ever see, a really honest man, unaffected and good company”. In effect, the members of the diplomatic corps were very glad that they were allowed to enjoy themselves with foreigners because their office prohibited any access to patricians.

Nevertheless, with these people, whose defects and bizarre manners suggest a cultural decline, a taste for the arts and curiosity about intellectual matters continued to live on. It seems indeed that, as a last privilege, nations that have achieved an elevated felicity conserve, even in moments of agony, a small ray of their brilliant imaginations, saving their vicious decrepitude at least from ridicule and shame.

18. Carnival. Oil on canvas.

The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle.

19. The Return of the Bucintoro, on the Day of the Ascension.

Aldo Crespi Collection, Milan.

20. The Molo, looking towards the West, c. 1727.

Oil on copperplate, 43 × 58.5 cm.

Private Collection.

4

The libro d’oro was destroyed in 1797 during the wars of the Republic, but some copies still exist. Like Venice, several other Italian cities had nobility registries.