Читать книгу Olonkho - P. A. Oyunsky - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTranslating the Olonkho

‘A MASTERPIECE OF ORAL AND INTANGIBLE

HERITAGE OF HUMANITY’

Alina Nakhodkina

Dr of Philology, Project Coordinator,

M. K. Ammosov North-Eastern Federal University, Russian Federation

INTRODUCTION

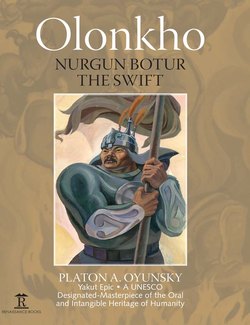

The Yakut folklore tradition is represented by a powerful and picturesque genre – the heroic epic known as the Olonkho. In 2005, UNESCO proclaimed the Olonkho ‘a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity’. This highly significant new status prompted a series of important events in the Sakha Republic, including the implementation of the State Programme on Preservation, the Study and Dissemination of the Yakut Heroic Epic Olonkho, the establishment of the NEFU Research Institute of Olonkho, the Olonkho Theatre, the Olonkho Land, the Olonkho Portal and many others. In 2007, at the M.K. Ammosov North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk, UNESCO’s proclamation also prompted the start of the Yakut-English translation project of the greatest of the Olonkho stories known as Nurgun Botur the Swift, first recorded by Platon Oyunsky.

An Olonkho hero

THE WORKSHOP IN 2007

The idea of translating Platon Oyunsky’s Yakut epic of Nurgun Botur the Swift, the first written, the most popular and longest – and certainly almost sacred – text into English first crossed my mind in 2003, but when I discussed the proposal with various specialists and friends everyone tried to discourage me, immediately pointing out the complexity of such a project. I nevertheless held a workshop on the Yakut epic for future translators, in which leading researchers of the M. K. Ammosov North-Eastern Federal University took part, including Professor Vasily Illarionov, Professor Louiza Gabysheva, Professor Nadezhda Pokatilova, Dr Vasily Vinokurov, Dr Ekaterina Romanova and Dr Svetlana Mukhopleva of the Institute on Humanitarian Research and Problems of Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences. By that time the first song of Oyunsky’s Olonkho had already been translated into French and English. It was for this reason, given their experience in Olonkho translation, that the workshop was also attended by the faculty of the Department of French Studies, represented by Dr Lina Sabaraikina, Dr Lyudmila Zamorshikova, and Assistant Professor Valentina Shaposhnikova.

The workshop turned out to be very worthwhile, since our gathering provided a platform for communicating my plan to the scientific and translators’ society in the Republic, which predictably prompted a debate in which both our supporters and opponents participated. Our opponents had stated that we did not know the Yakut language of the Olonkho, but they totally ignored the fact that Otto Boetlingk, Yankel Karro, Douglas Lindsay and Kang Duck Soo were not Yakut native speakers and had translated various pieces of Olonkho into German, French, American English and Korean respectively. I suggested that we, modern Sakha scholars, knew the Yakut language better than non-native speakers and therefore through our superior command of vocabulary and idiom we could produce a far better translation than theirs.

THE TEAM OF TRANSLATORS

I then came to realize that our old Yakut was not that sophisticated and so decided first to translate the Olonkho from the Russian version. It seemed to be a good idea because the translation was intended for English-speaking readers for whom the main priorities were a plot and characters. However, I soon discovered omissions and mistakes in the Russian translation which was disappointing, and at the same time I became more and more captivated by the richness of the Yakut language of Olonkho. Certainly, we lost some time on the Russian-English translation but we still found the strength, will and enthusiasm to start again – this time translating the epic from Yakut into English. At this point, I turned to Albina Skryabina, a former university professor and my teacher, who once had translated the first song of Nurgun Botur the Swift into English for some translation contest, and asked her to join our team of translators. Now her translation opens the English version.

I also had the idea that we could use selected students’ translations for this project but then it quickly became clear that Yakut was not our only weak point, but it was the standard of our English as well. We were a team of non-native speakers in which the students were the weakest part. Consequently, I had to reject the idea, but still appreciate those students who worked on the translation, and I sincerely hope it was a precious experience for them. Some fragments of their translation in Songs 5 anf 6 made by Agrafena Ivanova, Zoya Kolmogorova, Irina Popova are included in the present edition. Time flew by and some former students became our colleagues. Only three of them kept the desire to translate: my post-graduate student Zoya Tarasova, who translated the second song, Lyudmila Shadrina, who translated the fourth song, and my assistant, Varvara Alekseeva who revised and translated Songs 5 and 6, and with whom I translated Songs 7-9. An experienced translator, Sofia Kholmogorova, also joined our team and translated the third song. While revising all nine songs of the Olonkho Dr Svetlana Yegorova-Johnstone, the British member of our team, proposed her own translation of some fragments of the text and together, working closely on the editing of the text, we shared many thrills and hardships of the creative process.

Our job would never have been completed were it not for the great contributions made by our proofreaders: Paul Norbury (Publisher, Renaissance Books, Folkestone, Kent, UK); and Geneviève Perreault (MA in Linguistics, translator, Laval University, Canada).

ABOUT THE OLONKHO

‘Olonkho’ is a general term referring to the entire Yakut heroic epic that consists of many myths and legends. Epic forms of folklore are created during the early stages of ethnos (cf. Russian bylinas [bi`li:na(s)]: tale with an epic plot) and in the case of the Russians it becomes clear that an ethnos appeared during the later stages of their development when such massive oral forms of folklore as epics were forgotten. There are famous world epics such as the Mesopotamian Gilgamesh, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, the Finnish Kalevala, the Buryat Geser, the Kirghiz Manas, the Armenian David of Sasun, and many others. And among them our Yakut epic Olonkho takes its own place.

A warrior fighting a demon

A warrior with a bow

As the Yakut epic researcher Innokenty Pukhov states elsewhere in this volume, the Olonkho is an epic of ancient origin; by name, it is directly related to the Buryat-Mongol epic, the ontkho. The epic originates from the times when the Yakut ancestors lived on their former homeland in the South and had a close connection with the ancestors of the Turkic and Mongolian tribes living in the Altay and Sayan regions.

The Olonkho is written in an archaic language enriched by symbols and fantastic images, parallel and complex constructions, traditional poetical forms and figural expressions (‘picturesque words’ or ‘kartinniye slova’ in Russian – a term used by A.E. Kulakovsky, a famous Yakut writer and philosopher). The language of the Olonkho is rich in various figures of speech, especially metaphors, similes, epithets and hyperboles. The Olonkho is full of descriptions, as it is generally a descriptive work.

Thus, constant epithets are linked to the names of characters thereby connecting various fragments of the narration:

Mighty Nurgun Botur the Swift,

Who rides a fleet of foot black horse,

Born standing on the border

Of the clear, white sky (Song 5)

Fair-faced Tuyarima Kuo

With the nine-bylas-long braid (Song 1)

Born in the age of enmity

Ehekh Kharbir, Three Shadows,

The night stalker,

The deceiving twister

Whose whirlwind turns everything upside down,

Mighty Timir Jigistei,

The famous Ajarai. (Song 3)

The Olonkho’s bright artistic images and stylistic devices, elaborate poetic language and metaphors are close to the linguistic consciousness of the English-speaking readers knowing the poetic tradition of world epics.

TRANSLATION ISSUES

The most difficult aspects of translation are traditionally phonetics, syntax and lexical and cultural gaps.

Phonetic problems started with the transliteration of diphthongs. There are four diphthongs in the Yakut language that are as frequent as monophthongs: уо [uo], иэ [ie], ыа [ϊɜ], үө [уɛ]. The diphthong consists of two elements – a nucleus and a glide – and the nucleus has priority in pronunciation. I used this phonetic peculiarity in the translation to make Yakut names and nouns shorter and more readable, for instance ‘Суодалба’ [suodal`ba] became ‘Sodalba’; ‘Иэйэхсит’ [iejeh`sit] – ‘Ekhsit’; ‘ыhыах’ [i`hieh] – ‘Esekh’; ‘Күөгэлдьин’ [kjuegel`jin] – ‘Kegeljin’. I made an exception for diphthongs in one-syllable names and nouns such as ‘уот’ [uot], which was translated either as ‘Uot’ as part of a name, or as ‘Fiery’ as part of a constant epithet attached to the name.

I transliterated some exotic monophthongs based on their phonetic environment and the context, e.g. the Yakut letter ‘ы’ [i] is transliterated either as ‘y’, which is more traditional, or ‘i’. In general, while translating the epic, I ignored almost all the rules of transliteration, since it seemed to me that words transliterated according to these rules would be cumbersome or at best slow down the reading. My goal was not to put off the English-speaking readers but to inspire them to go on reading this long poem.

Another phonetic obstacle was long vowels, for which I used the same strategy: I shortened long vowels in polysyllabic words and transliterated their approximate pronunciation, e.g. ‘Туйаарыма’ [tuja:ri`ma] was translated as ‘Tuyarima’; but kept to similar graphic forms in short words, e.g. ‘өлүү’ [e`lju:] – ‘Eluu’, ‘Айыы’ [aj`i:] – ‘Aiyy’, ‘алаас’ [a`la:s] – ‘alaas’, etc. Some words are spelt with ‘h’ in order to show their length or different pronunciation: ‘илгэ’ [il`ge] – ‘ilgeh’, ‘сэргэ’ [ser`ge] – ‘sergeh’.

A breast-feeding woman sitting under the tree of life

Consonants were also a challenge. Thus, Ҕ [ǥ] does not have a direct counterpart in English and may be interpreted as both [kh] and [g]. I chose the last variant as the closest equivalent, e.g. ‘Бохсоҕоллой’ – ‘Bo(k)hsogolloi’; ‘оҔо’ [o`g(kh)o] – ‘ogo’. This choice was motivated by a word ‘удаҔан’ translated as ‘udagan’ (shamaness) in earlier translations. Sometimes I used data from Russian translations, e.g. the words ‘ыhыах’ and ‘уда5ан’ in Russian have the following graphic forms ‘ысыах’ [i`sieh] and ‘удаганка’ [uda`ganka]. That is why I used ‘s’ in the English translation ‘Esekh’ instead of ‘Ehekh’ – besides, there is a demon in the Olonkho who has a similar name ‘Ehekh’ spelt with ‘h’.

Structural differences in the Yakut and English languages make it impossible to achieve an accurate transmission of phonetic means such as alliteration, assonance, consonance and rhyme involving equal rhythm, length and number of lines. But these phenomena can be compensated in translation by other linguistic means to transfer phonetic and syntactic features approximately. Fortunately, English poetry – as well as Yakut poetry – is based on alliteration. Of course, nowadays alliteration is almost transformed into a non-functional supplement to the modern English verse and becomes an ornamental element of it. However, alliteration is a traditional part of old German poetry (Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian). In many cases only alliteration gives a structural certainty to old English poems that are not free from some monotony and colourless rhythm. Therefore we see that alliteration is a key element of the old English verse and in this respect to use alliteration in the Yakut-English translation of an ancient epic poem is relevant.

Black horse lost,

Broil broke out…

Bride was contested,

Battle commenced,

Blood was shed,

Bayonetted eyes,

Broken skulls –

Brouhaha brewed (Song 7)

The fire burned

As big as a birch-bark barrel. (Song 6)

His strong muscles

Swelled and strained; (Song 5)

Where a fantastic sorcerous storm swirls and plays (Song 8)

We use compensation as the most efficient means to transform Yakut parallelism typical of the epic language into English parallel constructions:

Buhra Dokhsun oburgu,

Who has never been tamed,

Whose father is Sung Jahin,

Who has the thunder chariot,

Who flashes lightning! (Song 7)

Compensation also helped much in our attempts to transfer so-called ‘parnyie slova’ – a rhymed couple of words where the second component does not have any meaning and is added only for rhyming purposes but in our version both components have meanings:

The eight-rimmed, eight-brimmed,

Full of discord-discontent,

Our Primordial Motherland

Was created-consecrated, they say…

So, we do our best to tell the story… (Song 1)

A Sakha mountainscape

As mentioned above, some Yakut turcologists felt suspicious of the quality of the English translation of the Yakut epic because they believed that it was impossible to transfer all the richness and depth of the Yakut language into another language, especially an unrelated one. In response to this view, it is appropriate to cite the words of Roman Jakobson: ‘All cognitive experience and its classification is conveyable in any existing language. Whenever there is deficiency, terminology may be qualified and amplified by loan words and loan translations, neologisms or semantic shifts, and finally, by circumlocutions.’ [R. Jacobson, ‘On the Linguistic Aspect of Translation’, 1959.] This implies that in order to convey the same notion expressed in the Yakut language by a single term, a speaker of English must resort to employing different lexical strategies, such as circumlocution, neologisms and/or loanwords. Our English translation keeps some exotic words where there were lexical gaps -- for example, when expressing units of measures (kes, bylas). To avoid transcribing too many Yakut words we add their English equivalents, e.g. ‘илии’ [i’li:] is translated as ‘finger-sized’; ‘тутум’ [tu’tum] is translated as ‘fist-sized’, a hitching post for horses, is represented in two versions – both ‘sergeh’ and ‘tethering post’; the dwelling is either translated as ‘uraha’ and sometimes as ‘yurt’, being a more familiar word to English-speaking readers; the utensils ‘чорон’, ‘хамыйах’ and ‘кытыйа’ are represented by their English analogues ‘(wooden or silver) cup’, ‘bowl’ or ‘flat bowl’. The Yakut ‘кымыс’ [ki`mis] is also translated as one of the more traditional English forms ‘kumis’. All fire-spitting, many-legged and many-headed monsters translated in previous Olonkho translations as ‘serpent’ and/or ‘snake’ I translated as ‘dragon’, which is closer to the real nature of these creatures. All such transformations were necessary to concentrate the reader’s attention on the unfolding plot, which is already overwhelmed with bright unusual images and metaphors.

Onomatopoeic words and interjections brought their contribution to complicate the English translation: ‘Uhun-tusku!’; ‘Urui-aikhal!’; ‘Ker-bu! Ker-bu!’; ‘Buia-buia, buiakam!’; ‘Buo-buo! Je-buo!’; ‘Anyaha-anyaha!’; ‘Art-tatai!’; etc. The only exception we made was for the interjection ‘Хы-хык! Хы-хык! ([hi-`hik])’, transferred as ‘Ha-ha!’. In some cases we used explanations translating the meaning of interjections: ‘Look here’, ‘Listen to me’, etc.

The following example, taken from a draft translation of the Olonkho, shows how we tried to keep imagery and metaphors, i.e. the so-called ‘picturesque words’ in the translation:

| Орто дойду улуу дуоланаАан ийэ дайдытыттанАрахсан барда,Аабылааҥҥа тиийдэ,Күнүн сириттэнКүрэнэн истэ,Туналҕаннаах толооноТуoһахта курдукТуналыйан хаалла... | The great giant of the Middle WorldHad leftHis primordial Motherland,And come to the thicket,He was running awayFrom the sunny land,The bright surface of whichWas shining far behindLike a white patch on a cow’s head… |

This fragment describes Nurgun Botur’s journey to the Under World, while the sunny Middle World is left behind shining brightly as a white patch on a cow’s forehead. The picturesque word ‘туналый’ means ‘whiten/shine’, ‘lighten/glisten’, ‘radiate/beam’, and as such its semantic structure consists of the components ‘glisten, shine’ and ‘white colour’. The translation of the verb keeps only the component ‘shine’, but its second component is compensated in the word combination ‘Like a white patch on a cow’s head’.

Another one of the serious issues was the translation of polysemantic words which are used profusely in the Olonkho. For example, the word ‘түhүлгэ’ [tjuhjul`ge] – ‘tuhulgeh’ has a few meanings that hamper the choice of the right word: 1) a place where a festival is celebrated, or where people dance their round dance ohokai, which also refers to the name of the dancing circle, or a place for wrestling, or an Olonkho performance, etc.; 2) the festival itself, i.e. it can be a synonym for the summer solstice festival Esekh or any other fest (wedding party, etc.). Thus, in Song 9 the word has all the meanings simultaneously but I had to choose a concrete one and it was the festival Esekh:

They made

A wide and vast,

Joyful and bright

Esekh festival – tuhulgeh

On a beautiful copper surface

Of their blessed Motherland…

In conclusion, the Olonkho is a text with a high percentage of national-cultural components that make the process of translation extremely difficult.

An Olonkho hero