Читать книгу Olonkho - P. A. Oyunsky - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеOlonkho – the Ancient Yakut Epic

Innokenty Pukhov

Dr of Philology

Honoured Worker of Science of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia)

The extensive collection of Olonkho – the heroic legends of Yakutia – is the pearl in the crown of the Yakut peoples’ literary art, indeed it is their favourite and most distinctive type of literary art.

Innokenty Pukhov

Olonkho is the general name for the entire Yakut heroic epic that consists of many long legends. While their average length runs from ten to fifteen thousand verses, some of the longer Olonkho legends extend to over twenty thousand verses. In the past, Yakut Olonkho-tellers created even larger pieces by blending different plots together; regrettably those pieces were never recorded.

In actual fact, there is no specific data as to how many pieces of Olonkho existed during the time when the epic flourished. We can certainly say that there was ‘a significant number’ of them. Furthermore, it is very difficult to estimate how many pieces of Olonkho co-existed at the same time. The fact is that a plot of any one Olonkho piece can be more or less freely transferred into another piece, or simply reduced, by leaving out entire plot lines, or specific details, episodes, and different descriptions. The main characteristic feature of the Yakut epic, and the reason for the legends’ similarity, lies in the scope for ‘interpenetration’ and the opportunity to reduce or enlarge the length of Olonkho without ruining its content and the logical sequence of the events’ development.

The Yakut Olonkho is an epic of a very ancient origin. The stories originate from the times when the Yakut people’s ancestors lived on their former homeland and closely communicated with the ancestors of the Turkic and Mongolian peoples living in the Altay and Sayan regions. This is proven by the fact that there are common features in the Olonkho plot and the other people’s epic plots, as well as some similarities in the language structure and vocabulary. There are general features in the heroes’ names (khan – khan, mergen, botur, etc.). The word kuo in the main heroine’s name that the modern Yakut people had forgotten about serves as a permanent element of the name in its modern form.

In the other Turkic people’s epics a similar word ko means ‘beautiful woman’. In Olonkho the story-tellers sometimes add the particle alip to the name of the evil character, thereby changing its meaning to ‘an evil sorcerer’ (Alyp Khara). Alp and alyp are known among the Turkic peoples as words denoting ‘a hero’. Consequently, the Turkic alp (alyp) is represented in Olonkho as an evil enemy. In Olonkho there is such a notion as yotugen (yotuget) tyordyo. It is a place where all the Under World creatures live, the synonym of the Under World, the place, where these creatures bring their captives from the human tribes and torture them. Meanwhile, the ancient Turks used the word otiikan (or utiikan) to denote highlands in modern Northern Mongolia. Clearly, the notions alyp and yotugen entered the Olonkho narratives as echoes of past battles between the ancient Turkic and Mongolian peoples. There are many similarities in the verse structure and also the character of the descriptive passages in different episodes of the Olonkho and the Altay and Sayan people’s epics.

These similarities help to provide an approximate estimate of the timeline when the first Olonkho piece was created. The similar features of Olonkho and the epic of the Turkic and Mongolian peoples of Siberia could only have occurred in the period when there was direct contact between the ancient Yakut people and the ancestors of the Turkic and Mongolian peoples. By the time they reached modern Yakutia, due to the great distances and roadless terrain, the Yakut people had completely lost their links with their former neighbours. Thus, the ancient epic featuring these tell-tale links or connections in language and legend became the only remaining evidence of the earlier contact and interaction.

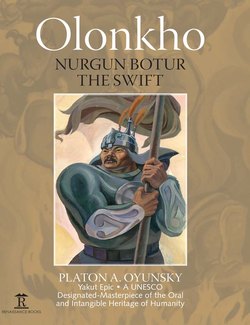

An Olonkho hero

As noted above, from the sixth to the eighth centuries, the Kurykans – the Yakut people’s ancestors – were in contact with the ancient Turkic peoples. The Yakut and Buryat legends show that the last Mongolian tribe with whom the Yakut had any contact (apparently in the North Baikal region) was the Buryat. This might have taken place some time before the fifteenth century. Possibly, it was during this time that the first Olonkho pieces begin to appear. On the other hand, given that the Olonkho has certain features that connect it with ancient Turks, it is quite possible that they originated at the end of the first millennium, approximately during the period from the eighth to the ninth centuries. According to its structure, the Yakut epic belongs to the later tribal period. There are some significant features, which prove that the Yakut epic belongs to the tribal period. These are: the Olonkho mythology, reflecting the patriarchal and tribal relations; the remnants of animistic views; the plots (battles with creatures); the remnants of the general tribal division of hunted goods (remaining in some pieces of Olonkho), and exogamous marriage.

Facts such as the ancient peoples using bows and arrows both as combat weapons and as working tools (during hunting) also prove the above statement. What proves conclusively that it is indeed an epic of the later tribal period, the time of ‘military democracy’ among the Turkic and Mongolian peoples of Siberia, is the type of cattle-breeding activity of the heroes – both developed forms of cattle-breeding, but especially horse-breeding predominates. A hero is always featured on a horse, the horse being his best friend and help-mate. His rival, on the contrary, is usually depicted on a bull in a sleigh team or astride a horrible creature. Fishing and hunting are in the background, they play a secondary role (the hero hunts only at the beginning of his life). Tribal society is practically divided into heroes (tribal aristocrats and chiefs) and their servants – house-workers that are considered to be lesser members of the family and society generally. The hero is the chief of his entire tribe, and, of course, the younger heroes obey him. There are some aspects of a fledgling division of labour; there is a blacksmith and smithy. Blacksmiths make ironwork tools and combat weapons. A well-developed and strict religious system also proves that the Olonkho is an epic of the later tribal period. There is an ‘Olympus’ – the home of all the good deities, led by Urung Aar Toyon (The Great White Lord). Evil Under World, or Hades, (the world of dual) evil chtonich creatures, led by Arsan Dolai, are opposed to the good deities. His people, Abaahy, do evil and harass others. Apart from the Upper World (the sky) and the Under World, there is a Middle World, i.e. the earth itself. The Middle World is inhabited by people, as well as by spirits of different objects, called echi. Every living being, every object in Olonkho has its echi spirit. Aan Alakhchyn Khotun, the goddess and the spirit of Earth plays a significant role. She lives in the tribal sacred tree called Aar-Luuk-Mas (‘Tree of Life’). The goddess of Earth helps the hero and his people, requests other gods to help the people, blesses the hero leaving on a long journey, and sustains his strength, by letting him drink milk from her breasts. During his journey the hero needs the sympathy of echi spirits of different locations – mountain ranges, rivers and seas. He has to give them gifts, so that they willingly let him pass through their territory, without causing him any trouble.

Olonkho describes a person’s life starting from his birth. Once the human being is born, he starts to organize his life, overcoming various obstacles that he meets along the way; the creators of Olonkho see these obstacles as creatures that pester the human being’s beautiful country. They destroy and demolish all that lives in this country. The human must clear the country of these creatures and create a rich, peaceful and happy life for all. These are the ultimate goals set before the first human; that is why he should be an unusual, wonderful, destined hero, sent specially from above:

To defend the sunny

Uluses,

To prevent the death of

People.

In all the Olonkho pieces the first man is a hero.

The hero and his tribe are heaven-born. That is why the hero’s tribe is called ‘Aiyy kin’ (the deity’s relatives). ‘Aiyy kin’ is the name of the Yakut ancestors, the creators of Olonkho. According to his important role, the hero is depicted not only as strong, but also as a handsome and well-built man.

The person’s physical appearance in Olonkho reflects his internal state. That is why the hero, Nurgun Botur the Swift:

Is as slender as a spear,

As swift as an arrow,

He was the best among all,

The strongest among all,

The most handsome among all,

And the bravest among all.

Nobody would stand a chance

In the hero world.

But the hero is, first of all, a mighty person, leading deathly battle. Therefore, he is also depicted as a majestic and threatening hero:

He is as big as a cliff,

His face is menacing,

His forehead is protruding,

Sharp and stubborn-like;

His thick veins

Stand out on his entire body;

They throb and heave

With the blood running through them.

His temple is sunken,

His nerves carefully quiver

Under the golden skin.

His nose is straight,

And he has quite a temper.

As a rule, the Olonkho characters are all different. If the main hero is a good defender of the people, who saves everyone in times of trouble, then the representatives of the ‘Abaahy kin’ tribe (literally, the demon’s relatives) are represented as evil and ugly creatures; they are one-armed and one-legged Cyclops. They represent all possible kinds of sin and evil, such as wrath, cruelty, bestiality and impurity. The Abaahy (evil) characters attack people, rob and destroy their lands, and kidnap women. In Olonkho, kidnapping a woman is a symbol of all possible insults, offences and humiliation towards the people. Having said that, the Abaahy characters have some human features. Their interpersonal relations are built on the principles of the humans’ tribal interrelationships. Thus, Arsan Dolai has the features of the patriarchal race’s chief. During the course of some events the main characters hold conversations with such evil characters. The nature of these conversations is similar to the conversations of two rival tribes’ representatives. The main heroes make various bargains with the evil characters and Abaahy shaman girls: they make peace for a time, and swear an oath not to attack during the period of truce. Sometimes the main characters do not kill the Abaahy characters that they defeated, but let them go peacefully, with a promise that they will not attack people anymore, or they turn them into servants. In this sense, there are interesting marriage bargains between the defeated Aiyy heroes and the Abaahy shaman girls. The Abaahy shaman girls are very lustful and strive hard to get married to an Aiyy hero. In order to do so, they can easily betray their own brother, the main character’s bitter rival. Using their weakness, the defeated Aiyy hero gives the Abaahy shaman girl a false promise to marry her and strikes different bargains with her, aimed against her brother. The Abaahy shaman girl does not violate this treaty, but the Aiyy hero does. Sometimes the Aiyy heroes and the Abaahy become sworn brothers, but only temporarily, because in Olonkho it is considered impossible for the Aiyy and the Abaahy to be close friends and sworn brothers forever. All this shows that in Olonkho to some extent there are somewhat mythological and fantastic features of real ancient tribes’ representatives that the ancestors of the modern Yakut people fought with.

All the other Olonkho characters, parents and relatives, good and evil deities and spirits, shamans and shaman girls, messengers, slaves, ‘guards’ of different places and other supporting characters are grouped around the main good and Abaahy characters.

Among all these characters there is one significant character, a woman-heroine, who is the bride, the wife, the sister or the mother of the hero or other Aiyy heroes. The heroine is idealized as a woman of beauty and is kindness personified. She can be a mighty heroine herself, leading battles and defending herself and others. A mighty heroine can lead battles not only with the Abaahy mighty heroes, but also with the Aiyy main heroes and other mighty Aiyy warriors. She fights with the Abaahy characters for the same reasons as the mighty Olonkho hero, i.e. to defend the people (especially in those Olonkho fragments, where the main character is a woman).

Of course, mighty heroines fight with mighty heroes for other reasons. These reasons can vary. There are common cases of the hero and heroine’s ‘marriage fights’, which are a part of the ‘heroic matchmaking’, the hero’s marriage as a result of a mighty battle. The mighty heroine is not willing to get married to a weak hero, who is not capable of defending his family and his people at the right moment. For this reason, she, first of all, tests the hero in battle, tests his might and courage.

Welcome ritual for a Sakha bride and groom

However, the heroine most often tests the hero by treacherously making him face the Abaahy mighty heroes. While doing this, she not only tests the mighty hero, her fiancé, but also defeats the creature with her hands before the marriage, because in Olonkho it is impossible to live a happy life without defeating evil creatures. The hero in Olonkho gets weaker after marriage and is not capable of defending his family from Abaahy; in this case the son of the family, a hero of the second generation saves the family. There are cases when the hero for some reason does not wish to marry the heroine. In such cases this is followed by long battles between them. Again the woman purposely makes the hero fight with the mighty Abaahy, causing their defeat. In all such cases the heroine asks the mighty Abaahy character to ‘save’ her from the character pursuing her, by promising to marry him. The mighty Abaahy that believe her, battle the mighty hero and perish. There are cases when the Aiyy shaman girl entangles the hero by using magic and carries him with her. From time to time she throws the mighty hero to the Abaahy as ‘a special treat’ for them to eat. In such cases, the hero breaks the bonds, then battles and conquers the mighty Abaahy that tries to eat him. The themes of the hero’s and heroine’s battles can be quite different. In all cases there is a happy ending to the hero and heroine’s conflict: finally, they get married, produce children and live peacefully and happily ever after.

In general, the heroine’s character is more finely defined than the hero’s character. The hero is first of all a warrior. The woman is shown not only in battle, but also at home. In the household she is a good housemaid and mother. In battle she is as good as the mighty hero. Being the mighty Abaahy’s captive, she shows her mind’s special inventive power and heroism. On the contrary (and in accordance with the Olonkho tradition), before being captured, living in her household she is represented as a weak, helpless and soft woman. But when she is a captive, she becomes transformed. In order to save her child (most commonly the foetus of the baby, because the creature also captures a pregnant woman) and herself she becomes exceptionally inventive and uses clever methods to save her child (the one the creature wants to eat) and vindicates her honour, and then gives the hero clever advice to help him save her.

Such characteristics of woman became ingrained in traditional Olonkho and represent the idealization of a heroine – a cause of struggle and contention between Olonkho heroes. During the pre-revolutionary period [the author means The Great October Socialist Revolution of 1917 in Russia], Yakut society was changing into a classist society where women were oppressed and had no rights (although the woman’s position in the family remained quite independent). In ancestral society faced with severe life conditions, the ancient cattle-breeding Yakuts had no notion of established religious views on a woman so within the family women generally held a considerable position of influence. They were required to do as much as men did. All of this complicated women’s characteristics and roles in Olonkho. While heroes of different Olonkho epics hardly differ from each other, the woman’s image is always personalized in some way. Such personalization is not fully representative since the Olonkho women differ not in individual characteristics, not in intelligence or mentality, but in the role they play: some women, for example, are just beauties, a hero’s aspiration, some of them show their mettle when captured, others are heroes, etc.

Several typical images function identically in all Olonkho epics and are represented almost equally, without any changes.

One such typical (and very important) image is of a blacksmith named Kytai Bakhsy the craftsman. This image is mythological and it is typical of such a symbolic craft. The blacksmith is one of the most powerful characters of Olonkho. He can smith not only weapons and armour for a hero (as well as for his enemy) but is also a hero himself. In D.M. Govorov’s Olonkho ‘Strong Surefooted Myuldju’ the blacksmith forges a hero into a self-moving iron pike to enable him to cross an ocean of fire. Then after crossing it (having negotiated his way through traps set by his enemy), the pike can become both a hero and his enemy (the second is to elude the vigilance of the enemy’s guards, using water of life or death for example).

Another interesting character is the wise man Serken Sehen. He has much in common with an image of old and wise elder-aqsaqals from the Turkic epic. It is specific that Serken Sehen is wise not only because he knows all about everything and can give a hero any advice but also (even most importantly) because he can show the way to the enemy: to tell where and when he came, where he is now and how to find him. He is a typical taiga way-wise man. This character is unique as it is created by taiga people. He is depicted as a small (tiny as a thimble) wizened elder: his body became a thing of wisdom. However, this wizened elder can be much stronger than any powerful hero can. Therefore, everyone fears and respects him.

Slaves in Olonkho do not have their own names. They are named after the work they do. They are inconsequential characters and nobody notices them. However, there are two characters that stand out among the slaves in Olonkho. They are the shepherd Soruk Bollur and an old woman known as Simekhsin who works in a cowshed. They are both comic, even caricature, characters with volcanic tempers, full of cheerfulness yet also firmness. The clever but mocking shepherd Soruk Bollur always laughs at and makes a fool of his arrogant masters. In addition, degraded and scorned old woman Simekhsin shows how clever she is in a difficult situation and saves the day when her masters are confused and helpless. Under the inexorable logic of events, even in conditions of patriarchal slavery, people’s power bursts the bonds that tie them and they become free. This idea is expressed through the images of the slaves Soruk Bollur and Simekhsin.

Olonkho expresses not only mythologized images of the remote past, but also of more recent times when a representative of a tribe was named after his tribe. For example, there is the character of a Tungus hero. In the majority of Olonkho epics, he acts as a hero’s rival in marriage and loses out in the struggle for a bride. Although the character of the Tungus hero (he is usually named Arjaman – Jarjaman, P.A. Oyunsky called him Bokhsogolloy Botur) is fantastic and mythologized, he has some features of a real man as well (he is a taiga man dealing with hunting and riding reindeer). The Tungus hero struggles only for a bride, there are no other conflicts involving him. He is depicted as a smart, cunning and artful hero. In the relationship between the main hero and the Tungus hero the pursuit for a peaceful relationship between the Yakuts and the Tungus (swapping, common festivities) is clearly evident. It is hard to determine the date of origin of the Tungus hero since the main hero’s rival in Olonkho. It could be on the Yakut’s present native land. (According to historical research, in the early days of their settling in Yakutia there were several conflicts between the Yakuts and indigenous tribes.) In addition, the Yakuts would have been able to meet the Tungus in the Baikal region. However, the heroic epic expresses these ancient relationships of the Yakut and the Tungus in the context of ‘heroics’ – fantastic heroic collisions.

In some Olonkho epics, the main hero and the Tungus hero are friends and allies; another epic shows the Tungus hero as the main hero. He struggles with Abaahy heroes and saves people. It is quite possible that the character of the Tungus hero in the role of the main hero is a result of late folk art, which suggests a higher plane of intelligence.

A significant role in Olonkho is taken by the hero’s talking and singing horse – a supporter, an adviser and an active participant at all the events in which the main hero is engaged. The horse not only gives advice to the main hero but also on occasion fights with an enemy horse and wins the battle. The heroic horse saves the defeated hero by carrying him away from the battlefield and by following his orders. Horse races are described as very exciting. The winner is the horse that comes first, so heroic horses go full speed and tear up hill and down dale, across the sky and under the ground. They are inbued with feelings – they rejoice in victory and regret defeat. The heroic horse is one of the most interesting characters of Olonkho. Olonkho-tellers describe it in detail, from point to point magnifying its strength, beauty and intelligence. Finally, this character more perfectly reflects the author of Olonkho – a genuine horse-breeder, a true horse devotee, a representative of his cattle-breeding culture.

As we have seen, Olonkho emphasizes a fantastic element as the means of expressing the heroic element. An Olonkho plot (which is both mythological and fantastic) shows the heroic nature of main heroes’ deeds which are not only related to the family. The Olonkho challenge is wider: it concerns the struggle for happiness and well-being of the whole tribe, which is the primary social entity. The main hero cherishes this idea of happiness, he struggles against evil, and he is always at the heart of events: the whole scene is focused on his life.

Therefore, biographical development of composition is typical of Olonkho: from the hero’s birth until his return home. His life is described as a chain of heroic deeds performed by him in order to achieve happiness for the whole world. The separate links of this chain of events form several episodes of Olonkho. The main story is sometimes interrupted by stories about misfortunes of other heroes of Aiyy kin attacked by monsters. Separate episodes and interwoven stories become a complete story only within a chain of all the events of Olonkho, and thus they are not inconsequential stories. They are elements of the whole story. In addition, here Yakut Olonkho-tellers show great imagination by inventing a huge number of stories and by weaving them into the fabric of the narrative. Such a composition is common to all Olonkho epics.

An olonkho warrior clubbing a demon

One of the main features of Olonkho as a genre is its specific historicism. Olonkho is created and represented as a history of humankind in the broad sense, indeed the history of the entire human society. Yet this story is unreal and fantastic and human society means only the epic tribe of Aiyy kin (ancestors of the Yakuts). The point is that any Olonkho epic describes the history of humankind since the origin of the universe, at least since ‘The Middle World’ settlement. Therefore, Olonkho describes thoroughly (in a fantastic and mythological manner) the life of the first people on Earth and their struggle for happiness, especially the life of the main Olonkho hero as his destiny is a reflection of the destiny of the whole tribe.

Olonkho is created in the lofty style in accordance with the significance of described events. At the beginning, the action gets off to a slow start but gradually events follow swiftly one after the other and turn into a flow of collisions. There are a number of symbols, archaic words as well as fantastic images in Olonkho. Its style is characterized by hyperbole, image contrast, parallel and complex constructions, traditional ancient poetical formulas – the ‘common places’, metaphors and figural expressions that move from one Olonkho epic to another. Olonkho is rich with different figures of speech especially with simile and epithets. Almost any broad description (Olonkho is full of descriptions as it is generally a descriptive work) includes not only separate similes but also complex simile constructions (several similes similar in form with many adjacent words with additional similes). Often epithets in Olonkho are complex as well. Sometimes similar syntactic constructions that enumerate objects are accompanied with characterizing epithets forming a common chain of epithets. All of this together creates a fascinating pattern, a sort of verbal arabesque. However, the elements of this pattern are not spread across but follow a strict inner system. Let us consider two examples to make the point. The first example describes the hero’s rising anger at having been insulted:

His hamstrings were strained,

Like a tough stem of a tree;

His legs were cramped,

Like a sash of a trap;

His large silver fingers,

Like ten grey weasels,

Pressed head to head,

His skin began to tear,

And his light clean blood

Sprinkled with convulsing trickles,

Like thin strands,

Of the horse with soft mane and tail,

His temple skin shrivelled,

Like bent bearskin bedding;

Lights of blue flame rose

Hissing from his temples;

Like a raked-up fire;

A flame large as a pot

Was dancing on top of the fire;

His eyes were scintillating with sparks,

Like sparks of a flint-stone;

When blood on his back

Boiled and roiled,

Approached his throat,

He spat and hawked

Splashes of scarlet blood.

This description is conditional (of course, Olonkho-tellers understand that such things are impossible). Its purpose is to extol the outstanding, fantastic, unique hero. The hero’s rising anger is depicted through changes to his appearance.

Similes make a deep impression although they are not impressive but simple: a trap, a weasel, strands of a horse’s mane, a bearskin bedding, fire, a pot, etc., i.e. those things that form part of the past life of the Yakuts (these similar similes create a parallelism of the whole phrase). Impression is deepened because all these simple things are compared with the fantastic events that happen to the hero in a tense moment. Such an effect is created by a contrast of scenes and the joining of ordinary and extraordinary things.

The same effect is created by epithets that describe a man’s condition and characterize objects offered for comparison. Let us look at this example:

(He) Built a winter dwelling

Along the endless southern ocean shore

Of the overflowing

Kys-Baigal-Khatyn ocean,

That throws out monstrous fish

As large as a three-year-old horse,

It emerged at the edge of the earth

And the snowy, white sky,

Dangling and touching (the ocean),

Like edges of sharp scissors,

Sowing a deep sprinkle of snow,

With buttons from bright stars,

With a whip of formidable lightning,

Accompanied with lumbering thunder,

Over-salted by crimson clouds,

Looking like spread wings and tail

Of the endless sky white crane

With a coloured beak,

And rings around the eyes.

It is the description of a winter dwelling constructed. Nevertheless, such a specific description is a basis for the whole picture creation: the space and the fantastic ocean that borders the sky and throws out monstrous fish.

An epic warrior flying on his horse

The thought that the seashore, where the winter road is built, borders the sky undoubtedly resulted from an observation of the horizon. This image serves to show the significant hyperbolic size of the ocean. In doing this, the authors not only show that the ocean borders the sky, but also give a description of the sky through the description of its ‘elements’. This approach is connected with the Olonkho tradition and the entire Yakut traditional song art: all the objects mentioned in traditional songs that play a significant role in the plot’s development are more or less intimately described; but in this case it is not only tradition that plays a role. The fact is that the first human on earth built the winter house; it was built in a wonderful land, the centre of the earth, created for a happy life, and thoroughly praised in the introduction of Olonkho. Thus, ‘the description’ of the sky connects the home and the land where the house is built with the entire universe; and it is a part of praising the land and the human who is predetermined by the gods to live on this land. The text starts with an epithet of a white crane, which is a part of the simile group together with the word ‘cloud’. It is an accepted tradition to portray an image of a white crane flying high up in the sky; it is the Yakut people’s most favourite bird, used in Yakut traditional songs as well as in Olonkho in order to characterize the broad sky. A large number of songs are dedicated to the white crane, described as follows:

The white crane of the endless sky

With a painted bill,

With rings around its eyes –

are the loci communes.

In the first example (the wrath of the mighty hero) everything was based on a chain of similes, but in this example a chain of epithets plays the main constructive role, characterizing separate ‘elements’ of the sky: clouds, snow, lightning, thunder and stars. Such a descriptive structure, taking the form of an enumeration and leading to parallel constructions with complex expressive means, is one of the main stylistic peculiarities of Olonkho.

In the example given, we have shown a typical tendency of Olonkho and of the entire folklore of the Yakut song tradition wherein the narrator gives a description of nature by describing an object (a home in this case) which does not refer to nature itself.

There are a great number of repetitions in Olonkho. Epithets are most frequently repeated with the names of the heroes, heroines, mighty Aiyy and Abaahy, as well as with the names of countries, worlds and the nicknames of the mighty heroes’ horses. They can be complex and contain an entire description. The epithets characterizing the mighty heroes’ horses are especially rich and complex, and also quite grotesque. This is due to the fact that the description of the mighty horse is an element of the hero’s description; thus, the more handsome and mighty the horse, the stronger and more majestic the mighty hero, its owner. A constant enumeration of epithets characterizing the horse every time the narrator mentions the hero’s name is a traditional feature of Olonkho.

There may be any number of pieces setting out the entire epic that are more than ten thousand verses long. These large repetitive fragments of text often contain the key parts of the epic: stories about various important events, about the story of the heroes’ rivalry, about the heroes’ origins. For this reason, such repetitions most often appear in the different characters’ long monologues, in which they express their attitude towards the events taking place, explain their actions, etc. While retelling the events in monologues, each character repeats word-by-word what the previous character (usually his rival) has just said about that event; sometimes the character tells something that we already know and that has already been mentioned a number of times before in previous events. What is most interesting is that the same events take on a completely different aspect in the speeches of the different characters.

Repetitions help with memorization of the text, which is quite important, owing to the length of Olonkho in oral performances. They also play an important compositional role. Repetitions play a supporting role for the epic, tying the various portions of its text together: they focus the listeners’ attention on the most important parts; link together events that take place at different times and are interrupted by other episodes; they also help to convey the characteristics ascribed to the main characters and events.

The long introductory descriptions of the main character’s land, of his homestead with its buildings, and of the house itself and its interior are a typical feature of Olonkho. Special emphasis is given to describing the land’s central point, a sacred tree called Aar-Luuk-Mas (‘Tree of Life’). These introductory descriptions can run to 1,500-2,000 verses. There are many descriptions found further on through the Olonkho plot as it unfolds. They include descriptions of other lands to or through which the main character travels; the physical appearance of friends and foes, the bride and her parents; Esekh (a Yakut traditional festival); and the mighty heroes’ battles, campaigns, etc.

The interpenetration of the plots gives them a special flow and the ability to freely reduce and expand. The same can be said of the descriptions. They can also be reduced or expanded. Olonkho-tellers often not only significantly reduce the introductory descriptions, but may also simply omit them, saying: ‘They inhabited the same land and the same country as in all Olonkho stories.’ Different portions of Olonkho existed independently in the vast land of Yakutia, separate parts of which were greatly disjoined in the past; this gave rise to different traditions in telling the entire Olonkho and its component parts – the introductory descriptions in particular. In the past, Olonkho was told by special master narrators without any supporting background music. The Olonkho characters’ monologues are sung, while the rest of the text is recited rapidly in a singsong voice, similar to a cantillation. One person performs the entire Olonkho: Olonkho, in fact, is a one-man performance. The performance of songs sung by different characters with different tone quality and tunes is a typical feature of Olonkho. The performers try to sing the mighty heroes’ parts with a bass voice, the young mighty heroes’ parts with a tenor voice, and the parts of the mighty Abaahy with a purposely untrained harsh voice. There are also the songs of heroines and elders: the hero and heroine’s parents; Serken Sehen, the wise man; the slave, who is also a horse wrangler; Simekhsin, a slave woman; the Aiyy shamans and the Abaahy shaman girls (their voices differ from those of the Aiyy shaman girls in their harshness and somewhat crazy dissoluteness) and so on. Imitation of animal sounds plays a noteworthy part in Olonkho songs: the horse laugh, the voices of different birds and animals. Outstanding Olonkho-tellers managed to express such a variety of sounds that it gave Olonkho an exceptionally bright, picturesque character, and the listeners were always impressed by the performance.

In the past, every Yakut person knew a great number of different Olonkho stories from childhood and would try to repeat them. There were always many professional Olonkho-tellers in the community. In autumn, winter and the hungry spring period, some of them travelled to different regions of Yakutia to sing Olonkho. What they received in payment was not particularly big, and they were usually paid in kind: a piece of meat, some butter or some grain. Singing Olonkho was a secondary job for them. All the Olonkho-tellers had a traditional household to look after, which, as a rule, was quite poor. Apart from social reasons, Olonkho-tellers were poor because they were competing with famous professional travelling artists and poets. Nevertheless, Olonkho-tellers were enthusiastic about their art: they devoted much of their time to it, learning the text by heart, listening to other Olonkho-tellers, memorizing their versions of Olonkho separately and as a whole, and linking them into their own version. In the same way, it took them a long time to practise singing and recounting the epic. It was therefore difficult for them to take care of their household and they often failed to do so and often enough abandoned it. The family of such a ‘professional’, rarely seeing its head, often lived in great poverty and hunger in winter. My friend, Dmitry M. Govorov (1847–1942), one of the most famous Yakut Olonkho-tellers, lived such a life. He was from the village of Oltektsy 2 in today’s Ust-Aldan region. He earned a living only at the end of his life, during the Soviet period, when he started to receive payments for his Olonkho recordings and publications and when he went into collective farming (kolkhoz). And yet these uneducated, poor Yakut Olonkho-tellers created and passed on the greatest epic creation of universal importance to our generation.

Recently, due to the widespread distribution of literature, theatre and radio, there has been a decrease in the number of live Olonkho performances, and it is even disappearing in some regions of the Republic. Nevertheless, the people still love and cherish it. Newborn children are named after favourite Olonkho characters – such as Nurgun and Tuyarima. Olonkho continues to be available and exists in new formats: books, radio broadcasts, and theatre and concert-hall performances. Olonkho performance falls within the domain of theatre and popular music.

Being the focus of the national art of the past, Olonkho had a great influence on the birth and development of Yakut literature and art.

Platon A. Oyunsky (10 November 1893–31 October 1939) was a famous poet, the founder of Soviet Yakut literature, a distinguished public and government figure, an active participant in the Revolution and the Civil War, and one of the first organizers and leaders of the Soviet government in Yakutia. He was the one who recorded the Olonkho story Nurgun Botur the Swift.

Platon A. Oyunsky

P.A. Oyunsky is one of the first Soviet Yakut researchers; he was a philologist, an ethnographer, a folklorist and a specialist in literature studies. He had an outstanding knowledge of Yakut folklore, especially mythology and Olonkho. He wrote many scientific works.

At the same time, P.A. Oyunsky was a great Olonkho-teller himself. Here it should be noted that all the early Yakut writers and poets (both revolutionary and Soviet) knew well, loved and cherished Olonkho. It is reasonable to say that they all must have known many plots and even entire Olonkho texts from their childhood; they sang and told them. Most of them became true Olonkho-tellers when they became writers, and told and sang Olonkho alongside their writing career. For example, Semen S. Yakovlev (Erelik Eristin), who lived at the same time as P.A. Oyunsky, and Mikhail F. Dogordurov, a writer, were also Olonkho-tellers. A modern national poet of the YASSR, Dmitry M. Novikov (Kunnyuk Urastyrov), is also an Olonkho-teller. Dmitry K. Sivtsev (Sorun Omollon), a national writer of the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (YASSR), is the author of a drama and opera based on the plot of Olonkho. The poet Sergey S. Vasilyev wrote a children’s version of Olonkho.

Traditional Sakha elders

It is not surprising that the first Yakut writers of the pre-Revolutionary and Soviet periods knew Olonkho well, loved it, and were even Olonkho-tellers themselves. As mentioned above, Olonkho played a significant role in the life of every Yakut person from childhood. Olonkho was one of the sources of Yakut literature.

As for P.A. Oyunsky, it is known that he had already become an Olonkho-teller in his youth. His childhood friend K.A. Sleptsov recalls the following:

Platon had a very serious childhood hobby which he managed to preserve throughout his entire life. It greatly influenced all his creative work. He adored listening to Olonkho songs and stories. The boy often went to his neighbour, Panteleymon Sleptsov, a great expert in Olonkho who was both entertaining and a singer. Platon would sit for long hours and listen to the wise old man performing his improvisations. Around the age of eight or nine, Platon started to tell and sing Olonkho to his friends. Later, the elders and the tent-dwelling nomads started inviting him to their homes with great pleasure. Everyone agreed that he had a great voice and a remarkable gift for speaking.

A distinguished artist of the YASSR, V.A. Savin, quotes a villager from the Churapcha village, who noted at a regional Revolutionary Committee meeting in 1920: ‘When Platon was very young he could already tell Olonkho well. I thought he would become a famous Olonkho-teller.’ There are some quotations of Platon Oyunsky himself: ‘In my childhood I had an exuberant, vivid imagination, I told the stories eloquently. Toyons invited me to perform and enjoyed listening to my stories in the long evenings while they were resting.’

All this was a part of the pre-revolutionary Yakut traditions: talented children would begin by listening to singers and Olonkho-tellers perform and would later retell the stories to their friends and to close neighbours or relatives. When the children grew up and became established, wealthy landowners would invite them to perform. The young Platon Oyunsky followed this path.

P.A. Oyunsky was born in the village of Zhuleysky, in the Tatta region (modern Alexeevsky region) into a family of limited means. There were famous singers and Olonkho-tellers in P.A. Oyunsky’s mother’s bloodline. This is what D.K. Sivtsev (Sorun Omollon) says about Zhuleysky: ‘The village of Zhuleysky is famous for its masters of traditional oral art: singers, Olonkho-tellers, and story-tellers.’ A famous Olonkho-teller, Tabakharov, also comes from Zhuleysky; a famous Yakut painter, I.V. Popov, once painted his portrait. Distinctively, the most famous Yakut singers and Olonkho-tellers came precisely from the Taatta region. The outstanding Yakut writers – A.E. Kulakovsky, A.I. Sofronov, S.R. Kulachikov (Ellay), I.E. Mordinov (Amma Achygyia), and D.K. Sivtsev (Sorun Omollon) – also came from the Taatta region.

When he became a famous poet and public figure, P.A. Oyunsky did not leave Olonkho behind (as is demonstrated by the foregoing); he continued cherishing it and singing it to his friends.

As mentioned above, Olonkho was not the only thing that P.A. Oyunsky knew and admired. He was knowledgeable about the entire Yakut folklore tradition. Folklore had a significant influence on his career, and it provided the native cultural grounding that he used to attain the summit of his creative achievements. The development of plots and themes in folklore led him to create wonderful literary works, which include a dramatic poem, ‘The Red Shaman’ (1917–1925), and the narratives ‘The Great Kudangsa’ (1929) and ‘Nikolay Dorogunov – the Hawk of the Lena’ (1935).

The play ‘Tuyarima Kuo’ (1930) is a noteworthy work in his writing career; it is a drama based on the Olonkho story Nurgun Botur the Swift and titled after the main heroine of that story. In the drama ‘Tuyarima Kuo’, P.A. Oyunsky is inspired by the main Olonkho theme relating to Nurgun, the hero’s battle with the creature called Uot Uhutaki (literally: ‘fire-breathing’). He preserves the main idea of the plot: the hero saves the people in trouble.

‘Tuyarima Kuo’ was something of a prelude to P.A. Oyunsky’s great work recording Nurgun Botur the Swift and is a model of successful Olonkho dramatization. It may be that it led P.A. Oyunsky to the fulfilment of a long-cherished idea to record the whole Olonkho. P.A. Oyunsky, of course, understood that no editing, no dramatization could give a complete and accurate picture of the great Yakut epic. Hence the idea to record the whole Olonkho as it is...

In the 1930s, ‘Tuyarima Kuo’ was staged at the Yakutsk National Theatre and was a great success. Later it became one of the sources for the creation of the libretto for the first Yakut opera, ‘Nurgun Botur’ by the writer D.K. Sivtsev (Sorun Omollon). P.A. Oyunsky’s principle works have been published in Russian more than once.

Nurgun Botur the Swift is one of the best and most popular Yakut Olonkho. P.A. Oyunsky reproduced it in its full length.

He appears to have recorded it very quickly. It is not possible to determine when the work started. The first song (out of a total of nine) was completed and published in 1930, and he wrote down the date when he finished working at the end of the ninth song: ‘1932, August 31. Moscow’. Overall, he spent no more than two-and-a-half calendar years on this Olonkho. In the years he was writing it, he worked (in Yakutsk), studying at a postgraduate school (in Moscow), and was intensively involved with the socialist Party and creative work. This left him little time for recording Olonkho. Perhaps, being an Olonkho-teller, he knew Olonkho by heart, which helped him to record them quickly.

Everything said above about the Yakut Olonkho applies to P.A. Oyunsky’s Olonkho Nurgun Botur the Swift. P.A. Oyunsky made no changes to verse, style, the traditional means of expression, archaic language, mythology and characters, conveying it in full, as it was sung. But a recorded folk Olonkho often combined rhyme with rhythmic prose – small prose inserts (e.g. in conversational turns). P.A. Oyunsky put it into verse.

P.A. Oyunsky’s Olonkho is almost twice the length of the longest of the recorded Olonkho (more than 36,000 lines of verse), although there were longer Olonkho. Previously, Olonkho were determined not by the number of lines, as is done now, but by the duration of the performance. To measure the wordage of Olonkho, a single night’s performance was used. An Olonkho performed in a single night was considered to be short (or rather, one might say, abridged); in two nights, medium; and in three nights or more, long. D.M. Govorov’s neighbours say that, depending on the circumstances (his own fatigue and that of his audience, whether he had to work the next day, etc.), he used to sing the Olonkho ‘Sure-Footed Myuldju the Strong’ over two or three nights. This Olonkho, as mentioned above, has over 19,000 lines of poetry. According to Olonkho-tellers, the longest Olonkho would be sung over seven nights.

Olonkho-tellers could extend the length of Olonkho. There were many ways of doing this. One was to add descriptions (scenery, surroundings of yurts, heroic battles and campaigns, etc.). For this purpose, Olonkho-tellers could bring in details and sophisticated visual means (e.g. additional simile) – in sum, they used to endlessly string together ‘embellishment’ techniques. This required from Olonkho-tellers not only virtuosity (P.A. Oyunsky was a virtuoso himself) and an excellent memory (and that he possessed too), but also a colossal amount of training and continuous practice in singing Olonkho (but this is exactly what P.A. Oyunsky did not do often enough). The reality is that all these ‘embellishment’ techniques and different descriptions were not merely contrived by the Olonkho-tellers (though improvisational skills were required and were inherent in the Yakut Olonkho-tellers), but were in ‘the Olonkho air’ in abundance and ready to be sung. The artist who was experienced and trained in the process of singing and recitation inserted them into his text, ‘glued’ them in so that they were naturally included in the text of the Olonkho.

There were amazing masters of such ‘improvised’ endless descriptions. This was known, for example, of Ivan Okhlopkov, an Olonkho-teller from the village of Bert-Uus nicknamed ‘Chochoyboh’. There is a story about how he once sang Olonkho in Yakutsk for the local rich family. He sang an introductory description which was not even finished by midnight. In other words, in five to six hours Ohlopkov recited only about three-quarters of an introductory description and did not sing a single song, did not tell any story.

Another way to extend Olonkho practised by Olonkho-tellers was through a contamination of plots. They would bring parts of other Olonkho into the main plot. They practised this only when the Olonkho-tellers and the audience had plenty of time.

P.A. Oyunsky apparently preferred the second way, as his descriptions in the complete Olonkho were not more than in other Olonkho. This does not mean that it had little in the way of description. On the contrary, it is possible to say that it contained a complete set of various descriptions, but they were not as sophisticated as, say, those in Olonkho by D.M. Govorov or (it is said) Ivan Okhlopkov. Among the recorded Olonkho there is one which can be considered as a basis for P.A.Oyunsky’s Nurgun Botur the Swift. This is also Nurgun Botur the Swift, recorded by an illiterate Yakut man, K.G. Orosin, in 1895 at the request of a political exile, E.K. Pekarsky, later a famous researcher.

Sakha lady in national costume

E.K. Pekarsky did much textual analysis on K.G. Orosin’s manuscript and included it in his ‘Obraztsy’. Interestingly, none of the other Olonkho recorded under the title ‘Nurgun Botur’ bears any relation to the plot of the Olonkho of the same name by K.G. Orosin and P.A. Oyunsky.

In Soviet times, a well-known folklorist, G.U. Ergis, released a separate publication, breaking the text into verses (but not touching the basis of E.K. Pekarsky’s textual analysis) and supplying it with a parallel translation into Russian with scholarly notes.

First of all, there is the interesting evidence of E.K. Pekarsky that K.G. Orosin learned this Olonkho from one of the Olonkho-tellers from Zhuleysky (the native village of P.A. Oyunsky). This means that Olonkho written by K.G. Orosin and P.A. Oyunsky have the same source. Comparison of the Olonkho texts shows that they are indeed variants of the same Olonkho.

I will not address all the similarities and differences between these two Olonkho. I will discuss the main one: The descriptions of the descent of Nurgun Botur from heaven to earth to protect people, the battle between Nurgun Botur, his brother Urung Uolan and the monster Uot Uhutaki, the salvation of warriors, captives and imprisoned in the Under World, and the occurrence and descriptions of many other events as well as many songs of heroes are basically identical. This can occur only with an Olonkho existing in one singing environment which is used as a source text by a number of Olonkho-tellers from one village or several adjacent villages.

But P.A. Oyunsky’s variant has many stories, personal details and descriptions that are missing in the version by K.G. Orosin. I will point out the main ones. In Orosin’s Olonkho, for example, there are no stories related to the battle against the hero Uot Usumu, and there are none related to the birth, upbringing and battle of the young hero Ogo Tulayakh, a son of Urung Uolan and Tuyarima Kuo. In K.G. Orosin’s Olonkho, there are no episodes associated with the Tungus hero Bokhsogolloy Botur.

It is difficult to say whether these stories were originally from Nurgun Botur the Swift or whether P.A. Oyunsky got them from other Olonkho. In any case, we must bear in mind that in the introduction to his Olonkho, he wrote that Nurgun Botur the Swift was created ‘out of thirty Olonkho’. When he said that he had created his Olonkho ‘out of the thirty Olonkho’, he was using poetic hyperbole, and the number ‘thirty’ was an ‘epic’ figure. Incidentally, in the past a love of hyperbole was common among Olonkho-tellers. To show how great their Olonkho was, Olonkho-tellers would say: ‘I created it by combining thirty Olonkho.’ Even so, it must be admitted that P.A. Oyunsky introduced stories into his Olonkho from other Olonkho. As mentioned above, this was a typical, traditional practice of Yakut Olonkho-tellers.

We can say with a high probability that P.A. Oyunsky took the plot about a slave called Sodalba from the Olonkho ‘The Shaman Women Uolumar and Aygyr’. Moreover, in this Olonkho, Sodalba is uncle of the young heroes, but in Oyunsky’s Olonkho he is a warrior-servant and Nurgun Botur turns to him. Usually, the hero, coming to his bride, because of whom a battle is to take place, masks and turns to a slave boy, the son of an old woman, Simekhsin. He does this so that the enemies who come to the bride before him will not notice him at first and will not take any decisive action.

In the Olonkho ‘The Shaman Women Uolumar and Aygyr’ the character of Sodalba is associated with avunculate, reverence for the maternal uncle and his assistance to his relatives. Interestingly, the avuncular Sodalba in the Olonkho about shaman women was transformed into a slave not only taking care of his nephews and fighting for them, but also obediently carrying out all their whims. Only at the end of the Olonkho does the slave Sodalba rise against and leave his young nephew-masters. P.A. Oyunsky (and perhaps his predecessors from Zhuleysky and neighbouring villages) included this remarkable image of the mighty slave in his Olonkho. The character of Sodalba in Nurgun Botur the Swift was introduced from another Olonkho, and it can be said with confidence that the transformation of the hero in the boy-servant was an age-old theme in all Olonkho presenting this situation.

But what is typical: the character of Sodalba in ‘Nurgun Botur’ somehow does not give the impression of having been imported. It is merged with the whole context of the Olonkho. These are the distinctive features of Olonkho and of the exclusive ingenuity of the Yakut Olonkho-tellers.

In P.A. Oyunsky’s version, the introduction contains a striking piece on the war among the gods and how they divided the three worlds. This pattern is absent not only in the version by K.G. Orosin, but also in all other Olonkho known to me. Apparently, this episode was once in the Olonkho, was forgotten and was then restored by P.A. Oyunsky, who used to listen to the great Olonkho-tellers like Tabakharov and Malgin.

All of this suggests that P.A. Oyunsky recorded his own version of ‘Nurgun Botur’ (as practised by him in live performance and perceived in a live performance), that it was not just a version ‘compiled’ or borrowed from others. These are some of the most significant features of P.A. Oyunsky’s Nurgun Botur the Swift. They show that this Olonkho, in its entirety, is within the tradition of Yakut Olonkho-tellers and represents one of the versions of people’s Olonkho, and that it is not just a ‘consolidated text’ arranged by a poet at a table.

Nurgun Botur the Swift was translated into Russian by V.V. Derzhavin – an outstanding poet and translator. He undertook this work after translating many works of classical poetry of the peoples of Central Asia, Iran and the Caucasus (Navoi, Ferdowsi, Nizami, Khagani, Khayyam, Rumi, Saadi and Hafiz). The works of these classics of the East in the translation of V.V. Derzhavin were published repeatedly. Widely known translations of ‘David of Sassoun’, ‘Kalevipoeg’, ‘Lacplesis’, ‘Raushan’ and other works of epic poetry were made by V.V. Derzhavin. The Uzbek writer and academician Camille Yashen said about V.V. Derzhavin’s works as a poet and translator: ‘The ingenuity of the translation skills of V.V. Derzhavin stands solely on faithfulness to the manuscript, careful and meticulous study of the culture of the people to whom belongs this literary masterpiece, and the ability to penetrate into the essence of the historical perspective of the author, to recreate the original tone and unique colours of his poetic world – in other words, the ability to make the Russian reader feel the flavour of poetry born in a different language.’

The same can be attributed to V.V. Derzhavin’s translation of the Yakut Olonkho; he worked on it for many years. Throughout that time he consulted with me continually about the translation of ‘Nurgun Botur the Swift’, and I would like to note his extremely attentive attitude towards this monumental epic.

Before translating, V.V. Derzhavin read books on the history, ethnography and mythology of the Yakuts, carried out a detailed study of all translations of the epic and folklore, as well as works on Yakut folklore. He consulted with me in detail on all manner of questions, seeking to deepen his understanding of the epic, as yet unknown to Russian and European readers. During all these years V.V. Derzhavin repeatedly met with me (and often with writers from Yakutia) and discussed all aspects and details of the Yakut epic and its translation and the difficulties encountered in the process.

His translation is fair and true and conveys the spirit and imaginative system of the Olonkho and its plots. Preserving the original style, he has recreated a parallel system in tune with the poetic system of Olonkho.

It is my deep conviction that V.V. Derzhavin’s translation of Nurgun Botur the Swift is a wonderful (I would say, a classic) example of poetic translation of the ancient epic of the Turkic-Mongol peoples.

1975

Translated by Nadezhda Noeva,

Yakutsk. 2012