Читать книгу Olonkho - P. A. Oyunsky - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

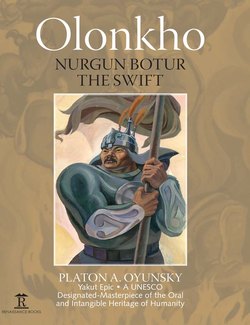

ОглавлениеForeword

by

Anna Dybo

Russian Academy of Sciences

The Yakut epic poems known as the Olonkho, along with the Mongolian Gesar, the Kyrghyz Manas and the Bashkir Ural-Batyr, which are typologically and genetically related, were quite rightly included by UNESCO in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

An Olonkho-teller (olonkhosut) describing a hero’s welcome

Huge poetical texts (rhythmically organized as alliterative stanzas) with an average of 15,000 lines of poetry are performed by the Olonkho-tellers (olonkhosut), in a similar way to the bards of Ancient Ireland or the aoidos of ancient Greece. It is spoken as a recitative or chanted as a song. The Olonkho is the quintessence of Yakut traditional culture.

For the translation into the English language Olonkho: Nurgun Botur the Swift has been chosen, partly because it is the most voluminous and partly because it is the one closest to the literary text. This is a heroic epic recorded, and to some extent re-created (as far as one may say that epic songs have authors), by the outstanding Yakut writer, scientist and visionary Platon A. Oyunsky. This year (2013) is Oyunsky’s 120th anniversary and this publication is devoted to his jubilee. To the Sakha people Platon A. Oyunsky is what Chaucer is to the English people: he is the founder of the modern Yakut literary language, as well as the author of a number of works of modern Yakut literature. He was also an olonkhosut, who collected into one work more than 30,000 lines of poetry. In his scientific works devoted to the Olonkho, Oyunsky has established both cosmogenic and cosmological myths, which form the background to the epic texts, giving a detailed description of the mythological picture of the world of the bearers of the Sakha (originally unwritten) epic poetry (epos). It is no accident that Nurgun Botur the Swift is in a significantly clearer form than any other epic text – revealing this particular Olonkho story before the eyes of the readers (and of course traditional listeners). According to Oyunsky, ‘Olonkho determined the world outlook of the ancient Sakha, it throws light onto the ancient period of life of the Sakha, their pre-history’.

It is difficult to establish precisely the time of creation of the Olonkho. As with any work of oral folklore, the text of Olonkho evolved through the Olonkho-tellers, enriched over time with new information about the life of the people. In the Olonkho texts one may find traces of history – thus they resonate with recollections of the great Mongolian emperor Genghis Khan and also reminiscences of more recent battles of the Sakha with the Tungus people, and, possibly, considerably earlier ones reflecting the fall of the Xiongnu empire. In Manas, for example, we also find mention of the Junghar state (17th-18th centuries.), of Genghis Khan (13th century), and of the conflicts with the Rouran Khaganate – one of the people which came onto the historic arena after the Xiongnu (3rd century BC to the 3rd century AD). Of course, all this can be used for dating but one cannot expect to do so with any great precision. It is frivolous, in my opinion, to try to establish the relevant periods (the folklorists tend to get preoccupied with it). Realistically, what we see in Olonkho are (a) references to the Junghar wars are not there – which means that in the 17th century, the olonkhosuts lived far away from the Junghar khanate; (b) references to the expansion of the Genghis Khan empire are abundant – which means that the olonkhosuts lived not too far from all the paths on which the Mongolians travelled (thereby contradicting the idea that the ancient Sakha settled on the banks of the Upper Lena in the 10th to the 11th centuries); (c) references to the second Turkic Khaganate are there, e.g. Etuken/Utuken etc. – from this we can infer that in the 8th to the 10th centuries, the olonkhosuts were settled not far from those places (and possibly already composed some proto-Olonkho); (d) the fact that many Olonkho have common plots with Mongolian epics shows that, above all else, there were contacts and we know from other sources that there were indeed contacts. V. Rassadin on the one hand, and S. Kałużiński and M. Stachowski on the other, divide these contacts into two distinct periods – one in the ancient Turkic epoque, approximately the same 10th-11th centuries with the dialects of the Daghur type, the other – with the Buryat around the 16th century. To ascertain the date of the earlier periods is hard, but the similarities of all the Turkic epics makes you think of the epoch of the disintegration of the proto-Turkic ethnos, that being – Xiongnu, the Han dynasty in China, i.e. from the 3rd century BC to the 3rd century AD. As for the struggle between tribal and feudal systems, this is not a guideline for dating because for the nomads feudalism came and went many times, eventually automatically collapsing into a tribal form in the countryside.

In the research works of the renowned folklorists and historians that are included in this publication some suppositions are made about the origin of the Olonkho; partially they are connected with outdated historic theories; but in general we should agree with the fact that the Olonkho epic shows considerably closer ties with other Turkic and Mongolian epics than with those of the Extreme North and, therefore, has been carried by the Yakut to their modern territory from the South.

The translators and editors have made an enormous effort, trying to adequately convey the poetic peculiarities of the Olonkho text into English – principally the poetic imagery directly connected with the vast landscapes of the North, and the ornate rhythmical text with an abundance of alliterations. The language of Olonkho is archaic, many words that are present in the text are no longer in use, one can only guess at their meanings. This language is waiting for its researcher(s).

It is very important that, finally, the English readership can acquaint themselves with yet another ancient and complex culture, comprising a huge territory, and up to now serving as a spiritual support to a whole nation. We should also hope that the appearance of this translation will stimulate new researches into the Olonkho in Yakutia itself as well as throughout the world.

Those who wish to acquaint themselves more widely with the texts of Olonkho and access the current scientific works on it should visit the Olonkho site created by the researchers: http://olonkho.info. The site functions in Russian, Sakha and English.