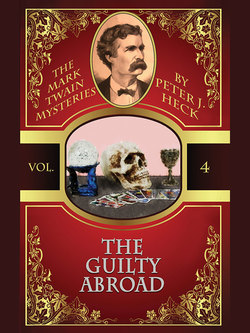

Читать книгу The Guilty Abroad: The Mark Twain Mysteries #4 - Peter J. Heck - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

6

ОглавлениеMcPhee and I led the policeman up the stairs to the apartment where the séance had been held. McPhee opened the door, and we were greeted by a cloud of tobacco smoke almost as thick as the fog outside. Mr. Clemens and Sir Denis DeCoursey had pipes burning briskly, and Cedric Villiers was smoking a sweet-smelling cigarette in a long amber holder. I suppose that to tobacco addicts, the chance to smoke was comforting. The three of them had (very understandably) decided that the little anteroom where McPhee had waited during the séance was a more pleasant spot to sit than the larger room with the doctor’s body. Villiers had taken up the deck of cards McPhee had been playing with, and was dealing them out in some sort of crisscross pattern on the table.

“Thank goodness,” said Sir Denis, rising to his feet. “It’s good to see you, Constable. We’ve got rather a sticky affair here.”

“I’ll do what I can, sir,” said the policeman. “But I’m afraid you’ll all ’ave to wait until someone comes from the station—the inspector or ’oever takes ’is place. If we’ve really got a murdered man ’ere, that is to say—might I see the body?” His manner was deferential, but quite firm.

“Yes, of course—right in here,” said Sir Denis. He opened the door to the séance room.

The lights were even brighter than when I’d left—there were several candles now burning in addition to the gas, and Dr. Parkhurst’s body was clearly illuminated. Someone had poked up the fire, as well, and added a few lumps of coal to the grate. The policeman walked over to the body and looked closely at it, not touching it, then looked up at us. “ ’E’s been shot, all right. There won’t be much work for the doctor. ’As ’e been moved at all?”

“Yes, he was over at that table when it happened,” said Mr. Clemens. “We all were.”

“Aye,” said the policeman, turning around. He saw the drying blood on the carpet and nodded. “And where did the shot come from?”

“Damned if I know,” said Mr. Clemens, scowling. “I was sitting right at the table with him, and I didn’t hear any gun go off. Didn’t see a flash, either. I’m getting up in years, but I didn’t think I was going deaf and blind, yet.”

“But there was an absolute racket of knocking and banging,” said Sir Denis. “Whoever did the shooting must have picked his time for the noise to cover up the report. Still, I’m surprised I didn’t notice it—I’ve been shooting since I was a lad, and I’d wager I’ve heard every kind of firearm made.”

“Perhaps the shot was from a distance,” I suggested. “Then it wouldn’t have been as loud, would it?”

“How could it have been fired from any kind of distance, in a room no more than fifteen feet across?” said Mr. Clemens, raising his eyebrows. “Besides, the whole place was darker than the inside of a black cat—you couldn’t see your hand before your face in here, let alone pick out one man to shoot at.”

“Well, dark or not, the gentleman’s got a bullet wound in ’is ’ead,” said the constable. “You’ll all ’ave to remain ’ere until the inspector comes to take your statements. Until then, I’ll ask you please not to touch anything so as not to muddle up the evidence. And it ’ud be best not to discuss what you saw or ’eard so as not to confuse your stories.”

“I don’t have no story,” said Slippery Ed McPhee. “I wasn’t even in the room when the shot went off—didn’t even know about it till it was over. I wish you’d let me say a word to my little lady, though. She ain’t used to rough stuff or gunplay, and I reckon she’s mighty disturbed by all this happening right in front of her eyes.”

“I don’t know about that—” began the policeman, but he was interrupted.

“Yes, by all means let the poor fellow speak to his wife,” said Sir Denis, putting a hand on the policeman’s arm. “The rest of us are clearly suspects, but Mr. McPhee could hardly have known what was happening in here, what with being in the other room. And he’s not spoken to his wife since the—er, unfortunate incident. It would be unnecessarily cruel not to allow him a word or two to comfort her.”

“I suppose there’s no ’arm in it, then,” said the policeman, nodding. “But I’ll ask you not to discuss what ’appened ’ere until the inspector’s come. Is that understood?”

“Sure, sure,” said McPhee, waving his hand dismissively. “Like I said, I didn’t see none of what went on anyways, so you can stop worrying. I just want to make sure Miss Martha’s all right.”

Sir Denis went and tapped gently on the door to the room where the ladies had retreated, and after a moment his wife, Lady Alice, peered out. “Mr. McPhee wishes to speak to his wife,” said Sir Denis. “Would she rather see him inside, or come out to meet him?”

“Best she come out, I think,” said Lady Alice. “Mrs. Parkhurst is still quite distressed. Wisest not to disturb her further. Just wait a moment and I’ll call Mrs. McPhee out.”

The door closed; we waited perhaps a minute, then it opened and Martha McPhee emerged. She seemed to have regained most of her aplomb since the violent termination of the séance, although I detected a touch of dismay as she glanced at the doctor’s body. “Edward,” she said. “I’m glad to see you. Are the police here yet?”

“I reckon so—that big lug over there ain’t a steamboat captain,” said McPhee, indicating the constable with a nod. “We’re just waiting for his boss to get here. Let’s go set down someplace a bit more comfortable.”

McPhee took her by the arm and led her into the little outer room, where they sat down next to each other. The rest of us followed, not so much to eavesdrop on their conversation as to get out of the room with the dead body. When they were seated, McPhee said, “How are you holding up, Martha? Are you all right?” That surprised me; it seemed out of character for McPhee to show concern for another person.

“I’m a bit shaken, I’m afraid,” she said quietly. “I wish I knew what happened—everything is a blur.”

“Well, I know even less than you, for once,” said McPhee. “Ain’t much a man can see through solid walls, you know. I guess the cops will sort it all out, and then we can go about our business.”

“Not if the cops figure out what your business really is,” growled Mr. Clemens. “More likely, they’ll put you on the first steamer headed west, and none too soon.”

“Sam, this ain’t hardly a time for jokes,” said McPhee, puffing up his chest. “I’ll ask you to respect this here young lady’s tender feelings, if nothing else.” Whatever he was going to say next, a firm knock on the outer door interrupted, and the policeman went to answer it.

A thin-faced young man entered, dressed in civilian clothes—a heavy topcoat over a brown tweed suit, with a bowler hat. His fair skin and light brown hair made him look very young, but I thought he might be a year or so older than I. Even so, it was evident from the constable’s deferential posture that this young man was of superior rank. “Hello, Wilkins,” he said to the constable. “What’s the matter here?”

“We’ve got a dead body in the next room, Sergeant,” said the constable. “Bullet wound in the ’ead, but these gentlemen say they never ’eard a shot.”

“Well, we’ll have to see about that,” said the detective, stepping through the door into the séance room. The rest of us began trooping after him, but he stopped abruptly a couple of paces into the room and turned around to face us—as it happened, Mr. Clemens was directly in front of him. “The body’s been moved,” said the young detective, waving an admonitory finger. From his expression, it might have been a crime equal to the actual shooting.

“Of course we moved him,” said Sir Denis, who had just cleared the doorway. “There was a chance he might live, and we wanted to get him into a more comfortable position. I fail to see the harm in that.”

The detective looked Sir Denis up and down, then wrinkled his nose fastidiously. “Don’t see any harm, do you? For your information, you’ve just addled any clues about how he fell, or which way he was facing when he was hit. And the lot of you have been smoking those stinking pipes in here, as well.”

“You’re damn right,” said Mr. Clemens, bristling. “Didn’t know there was a law against an American smoking his pipe anywhere he damn well pleased. And who the hell are you?”

“Detective Sergeant Peter Coleman of the Criminal Investigation Division, New Scotland Yard,” said the man, glowering at my employer. “There may be no law against smoking your pipe, but I wish there were. Now we’ve no way to tell which room the gun was fired from. Half the evidence is already gone, no thanks to you. The chief inspector won’t like this one bit when he arrives—which should be any moment, now. Can anyone tell me how long it has been since the shooting?”

“Not quite an hour,” said Sir Denis, stepping forward. “See here, Mr. Coleman, I know the smell of gunpowder as well as any man in England, and I can tell you without a shadow of a doubt that there was no odor—and no report, and no flash, either.”

“So you say,” said Coleman, looking down his nose at Sir Denis. “You may even be right, but I’d rather trust the scientific evidence—which you lot have gone and obliterated without a thought. Or, just possibly, you might have done it on purpose.”

“Young man, I resent your implication,” said Sir Denis. “Do you know to whom you are speaking?”

“To a homicide suspect,” said the detective. “Has anyone left the premises since the shooting?”

“No one’s left since I arrived,” said Constable Wilkins. “I can’t say what ’appened before that, Sergeant.”

“Mr. McPhee and I went out to notify the constable,” I volunteered. “Other than that, I believe everyone has stayed here the entire time.”

“McPhee, eh?” The detective turned to the constable. “I assume you’ve noted down everyone’s name, Wilkins.”

The constable swallowed. “No, sir, I’ve ’ardly ’ad the chance. You got ’ere so quick, I’d just begun—”

“I see,” said the detective, tight-mouthed. He pulled a small notebook and a pencil out of his pocket. “Well, we’ll just have to start at the beginning and do everything properly. You there, what’s your name and place of residence?” He addressed this question to my employer.

“Samuel Langhorne Clemens, of Hartford, Connecticut,” said my employer. “That’s in America, or was the last time I checked.”

“Are you attempting to be facetious?” said the detective. His expression was stony. “I don’t advise it—this is a very serious matter you’re involved in, I’ll have you know. Anything you say can be held against you.”

“Really? I hardly noticed how serious it was, I was paying so much attention to that dead man over there,” said Mr. Clemens, puffing vigorously on his pipe. “But I hope you won’t hold it against me if I try to be facetious. It’s what I do for a living, and they tell me I’m pretty good at it, by and large. Of course, being English, you might not be able to tell the difference.”

“Exactly what do you mean by that?” the detective began, but he was interrupted by a knock on the outer door. “That’ll be the doctor, likely enough, or maybe the chief,” he said. “Be a good fellow, Wilkins, and see who it is.”

“Aye, Sergeant,” said the constable, moving to the door. After a moment, I heard the door open and the constable said, “ ’Ullo, Chief Inspector. We’ve got quite a puzzle ’ere.”

“It won’t be such a great puzzle, once I’ve had a look at it,” said the new arrival, striding energetically into the apartment. He was a short, athletically built man—something in his face reminded me of a ferret, but his manner was all bulldog. He didn’t stop to remove his hat or overcoat, but came straight into the inner room where we were all standing.

“I’m glad you’re here, Chief Inspector,” said Sergeant Coleman, deferentially, although I noticed he looked askance at the new arrival’s pipe, which gave off a particularly noxious odor. “I’ve begun interviewing the suspects, sir.”

“Good man, good man,” said the new arrival. “I’ll just have a look around, and we’ll soon know what’s what.” He walked over to the sofa where the body lay, knelt down, and grasped it by the chin to turn the face toward him. He looked intently at the wound. “This man’s been shot,” he said, accusingly.

“Yes, sir, so we believe,” said Sergeant Coleman.

“Well, then, where’s the gun?” asked the chief inspector, standing up and peering round the room. “I can’t say I’ve ever yet seen a man shot without a gun, and I am no spring chicken.”

“We haven’t found the weapon yet,” Coleman replied.

“Well, then, either it’s hidden or it’s been spirited away,” said the chief inspector. “Where have you looked?”

“Well, sir, I’d just arrived, and I thought it better to get the suspects’ names and—”

“Aye, so you told me. Well, you go ahead with that business.” He stopped and looked at the rest of us for the first time. “Here now, I know that face,” he said, staring at my employer. “Haven’t I seen you before?”

“I reckon you might have,” said Mr. Clemens. “I’ve been to London a couple of times before, and sometimes they put my picture in the newspapers and magazines.”

“Do they, now? And what have you done to merit that?” asked the chief inspector. He was still wearing his coat and hat, and his pipe was filling the room with fumes even stronger than those coming from the other gentlemen’s pipes.

“Oh, a couple of things,” said Mr. Clemens. “Told the truth about kings and queens, and stood up against injustice, and took some people down a peg when I thought they needed it. Nothing anybody else couldn’t have done, if they took a mind to.”

“Now I’ve got it,” said the chief inspector, brightly. “I did see you in one of the magazines. You’re that American writer fellow, Train, Twain, something like that. Pleased to meet you—Lestrade’s the name, Chief Inspector Lestrade.” He pronounced it to rhyme with played.

“Always a pleasure to meet an admirer,” said Mr. Clemens, shaking Lestrade’s proffered hand. Then his expression turned serious as he continued: “But tell me, Inspector; my wife and daughter and some other ladies—including that poor fellow’s widow—are in the next room, there. I reckon they’d be a lot better off in their own homes. How soon do you think they’ll be able to go?”

“Ladies, eh?” said Lestrade, following Mr. Clemens’s gesture toward the closed door. “Well, we certainly don’t want to keep them here any longer than we need to, Mr. Train. This is an ugly bit of business, and no doubt about it. No place for a lady at all, really. But you see, we’ve got a murder on our hands.”

“Yes, I’d noticed that,” said my employer. “That’s why we sent for a policeman. We didn’t have much need for one before that.”

“Good, I’m glad you understand, then,” said Lestrade. “What we’ll have to do is get everyone’s name, along with a domicile or place of lodging, and statements from anyone who was present when this fellow was shot . . .”

“Well, that lets me clean off, sure as fire,” said McPhee. “I wasn’t in this here room at all when the hammer fell, and there’s a dozen witnesses can swear to that.”

“A dozen witnesses?” Lestrade’s eyebrows rose. “What, were there that many of you in the place?”

“An even dozen including the dead man, yes—though he won’t be much good as a witness,” said Mr. Clemens. “In fact, it was dark enough that none of us really counts for much as a witness.”

“Dark, you say?” asked Lestrade. He took off his hat and fanned himself with it. “Do you mean to tell me this fellow was shot while the lights were out?”

“Maybe we ought to begin at the beginning,” said Sergeant Coleman, timidly.

“Yes, I think we had best do that,” said Lestrade. He tossed his hat onto the table, and began to unbutton his overcoat. “This is a rum business,” he said. “As much as I’d like to let the ladies go, I’m afraid we’ve got to get some answers before we can let anyone leave the scene. Now, I’m going to have Coleman take your statements out in that room while I have a look around for clues in here.”

“Yes, sir,” said the younger detective. He turned and pointed to Mr. Clemens. “I’d just begun talking to this gentleman, and I think we’ll just continue with him. Come along, please.”

Mr. Clemens and I began to follow Coleman into the anteroom when Lestrade turned and said to me, “Hello, young fellow, where do you think you’re going?”

“I am Mr. Clemens’s secretary,” I said. “He may need my assistance.”

“I’m terribly sorry, but that’s just the kind of thing we can’t allow in the midst of a murder investigation,” said Lestrade. “The sergeant will interview you one at a time, and I’ll ask the rest of you to wait in the room with the ladies. Constable, will you see to it?”

“Yes, Chief Inspector,” said Constable Wilkins. “Gentlemen, if you’ll be so kind? You, too, ma’am.”

Politely but very efficiently, the constable herded us into the room with Mrs. Clemens, Susy, and the three other ladies, to wait our turn. Noting her husband’s absence, Mrs. Clemens turned a searching look toward me. “Where is Samuel?” she asked.

“They’re taking his statement,” I said. “I don’t think he’s in any trouble; they’re going to ask us all to give statements.”

“Well, I can give you my statement right now,” said McPhee. “I wasn’t even in the room, and I didn’t do nothing. They can’t find any flies on Ed McPhee, this time.”

“I’ll ask you to wait until you see Sergeant Coleman to speak of the case, sir,” said the constable. “You’ll all have your chance to talk, but until then, I must ask you to be patient.”

I did my best, but patience is hard to conjure up when one is waiting to be quizzed about a murder. At least, I was glad that they had taken Mr. Clemens first. He would have been extremely awkward company if he’d been forced to wait, and I was uncomfortable enough already—especially since I had every reason to believe that one of the people in the room with me was a cold-blooded murderer.