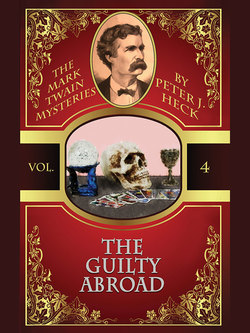

Читать книгу The Guilty Abroad: The Mark Twain Mysteries #4 - Peter J. Heck - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

7

ОглавлениеWaiting is hard in the best of circumstances. Standing in a small room waiting to be questioned by the police about a violent crime that took place in one’s presence would disconcert a saint.

With eleven of us in a small bedroom, there was not space for everyone to sit, even with a couple of chairs brought in from the outer room. And there was no room at all to pace. Cedric Villiers, McPhee, and I remained standing. I pulled out my watch for perhaps the third time to see how long Mr. Clemens had been talking to Detective Coleman. Half an hour. At that rate, it would be nearly four in the morning before the last of us had been questioned. Would they insist on interrogating the entire group before letting any of us go home?

At last, Mr. Clemens came stomping in the door, followed by Constable Wilkins, who looked round the room and asked, “Mrs. Parkhurst, would you be so kind as to come with me? And bring your purse, please. We’ll be needing to search it.”

The doctor’s widow stood up from the edge of the bed, where she had been sitting. Her sister, who had sat consoling her, stood and threw her arms around her. “Be brave, dearest Cornelia,” she said.

Mrs. Parkhurst nodded and squeezed her sister’s hand. “This will not be hard, Ophelia,” she said. “Believe me, the hard part is already over.” She smiled bravely and followed the constable out of the room. The door closed behind her, and the rest of us turned instinctively to Mr. Clemens.

He looked around the room at ten anxious faces and spread his hands. “Well, the good news is that I convinced that brass monkey of a detective to interview the ladies first, and to let each of us go home once we’ve answered his silly questions. So at least some of us will be able to get to bed at a sensible hour. The bad news is that he intends to go through the whole list tonight, so the rest of us will have to wait until he’s ready for us. Oh, and one more piece of news—a doctor came to look at the body while they were talking to me, and now it’s official, Parkhurst’s dead, shot by a person or persons unknown.”

“That’s hardly news,” said Sir Denis. “Nobody could have lasted long with that head wound.”

“Sure, but Scotland Yard can’t settle for something that obvious,” said Mr. Clemens. “That chief inspector’s out there going over the place on his hands and knees, tapping on floorboards and picking up specks of dust. If there’s been an ashtray spilled in that room anytime in the last week, I reckon he’ll know the make of every cigar that was smoked there, and whether it was lit with a match or off the gas. That don’t mean he’ll catch the shooter, but if they give medals for diligence, I’d bet he’s already got a bushelful.”

“That’s really brilliant,” said Cedric Villiers, his voice dripping sarcasm. “The fellow putters about looking for clues, when he’s got near a dozen eyewitnesses sitting here. Why doesn’t he send out for another interrogator so as to speed things up? Or better yet, do some real work himself? I’ll wager I’m not the only one who had other plans for the evening.”

“Don’t sell the police short,” said Sir Denis. He sat next to his wife on the windowsill, which had been fashioned into a comfortable-looking bench, just wide enough for the two of them. I could have seen it as a pleasant spot for reading or conversation, in other circumstances. “I’ve heard of this Lestrade from my friends in the Home Secretary’s office,” he continued. “They call him one of the best men in Scotland Yard, an absolute terrier. Once he gets his teeth into a clue, he’ll not let go until he’s followed it home.”

Cedric Villiers snorted. “That’s not what I’ve heard. Word is, Lestrade’s too bullheaded to be any use. He might have been a good man once, but he’s let success and promotion go to his head. I can believe it, after what I’ve seen tonight.”

“We’ll find out soon enough how good he is,” said Mr. Clemens. “Lestrade came in and listened some while that young puppy was trying to pry me open. He seemed to think it was important that nobody heard the gun go off. I reckon he’s right, although I’m not so sure he has to look very far for the explanation. All that other noise—”

“Never mind the other noise,” said Sir Denis. “I know the sound of gunfire, and I’ll swear there wasn’t a weapon fired within yards of me tonight.”

“That ain’t the half of it,” said Mr. Clemens. “Lestrade’s right about one thing, if nothing else—if a man’s been shot, there’s got to be a gun somewhere. Where the hell is it?”

“I wonder . . .” It was Hannah Boulton who spoke, her voice tremulous. She was sitting on the foot of the bed, wringing her hands. She looked to Sir Denis, as if asking permission to speak, and he nodded to her.

“Could it be possible that the shot was not fired in this world?” she asked, her eyes wide. “That would explain why we neither heard nor saw the weapon, and why it cannot now be found.”

“Good Lord!” exclaimed Sir Denis, slapping his forehead. “I’ve never heard of such a thing, but yes, it might account for the missing gun. Do you think it’s possible, Clemens?”

“I wouldn’t waste time on that idea,” said Mr. Clemens, shaking his head. “It’s against all common sense, not that common sense is all that common anymore.”

“The spirits you heard tonight are real,” said Martha McPhee, quietly. “I know that as well as I know anything.”

“Maybe so, but that ain’t the question on the floor,” said Mr. Clemens, pointing downward. “Even if there is a spirit world, and even if we heard voices from it tonight, you’re going to have a pile of convincing to do if you want me to believe that some spook took a potshot at the doctor.”

“I’m surprised at your lack of imagination,” said Cedric Villiers. “Surely, Clemens, you aren’t going to rule out the possibility of a supernatural agency without due consideration.”

“You’re the ones who ought to be ashamed at your lack of imagination,” said Mr. Clemens. “You haven’t even begun to look at all the perfectly natural explanations for what happened there tonight. Why, there must be dozens of ways it could have been done.”

“Name one,” said Villiers, with a smile that conveyed no warmth at all. “Will you be so kind as to elucidate the matter with one of your perfectly natural explanations, Mr. Clemens?”

“That’s the police’s job, not mine,” said Mr. Clemens. “If you’re promoting the theory that Dr. Parkhurst was murdered by a spook, go right ahead. There’s no law I know against spreading damn-fool ideas. But don’t waste your breath on me—tell it to that Detective Coleman, when it’s your turn to talk. I guess he’ll give it all the consideration it deserves.”

“There, so much for his natural explanations. He as much as admits that he doesn’t have one,” said Villiers, turning to the rest of the room with a superior smirk.

“Now, I wouldn’t sell ol’ Sam short—” McPhee began, but he was interrupted by the door opening to admit Chief Inspector Lestrade, followed by Constable Wilkins.

“Where’s the fellow who says he was in the other room when the shot was fired?” said Lestrade, looking at the group.

“That’s me, sure enough,” said McPhee. “But I didn’t hear no shot, no more than any of the others.”

“And I suppose you knew nothing about the peephole in the wall, did you now?” Lestrade shook his finger under McPhee’s nose.

“Peephole? Why, no, nothing at all about it,” said McPhee, doing a creditable job of appearing surprised.

“How long have you occupied this flat?” Lestrade continued. His gaze was fixed intently on McPhee’s face.

“Five or six weeks, I reckon,” said McPhee, shrugging. “Something just over a month.”

“And you’ve been giving these spiritualist parties the whole time, have you not?”

“Well, off and on, you know. A nonstop party would get pretty tiresome, with all the goings-on—”

“Yes, the goings on must have been quite impressive,” said Lestrade. “Did you install the apparatus, or was it all here already?”

“Apparatus? What in the world do you mean?” said McPhee, his face all innocence. I’d seen exactly the same expression when he’d claimed to have cheated me in order to teach me a lesson.

“I thought it was rather peculiar to find three bellpulls in the foyer of a little flat like this, and none anywhere else,” said the chief inspector, a feral grin on his face. “What do you think happens when you pull them? Or perhaps you already know, don’t you, Mr. McPhee?”

“I reckon a bell rings somewhere, is all,” said McPhee, shrugging. “We’re just regular folks, can’t afford no servants, so we hardly even gave ’em a look, did we, Martha?”

“Why, no, we’re not at all used to that sort of luxury,” said Martha McPhee. “What exactly are you intimating, sir?”

“Why don’t I just show you?” Lestrade said. “These people ought to know exactly what kind of chicanery you were up to so they can make up their own minds about your spiritualist rubbish.”

“Inspector Lestrade, I am sorry to learn that you are so closed-minded,” said Hannah Boulton, disapproval plain on her face. “I would have hoped that the police might have some concern for things beyond this earth.”

“Rubbish I said, and rubbish I meant,” said Lestrade. “Come into the next room, the lot of you, and I’ll show you something to open your eyes.”

Not knowing quite what to expect, I looked at Mr. Clemens, who shrugged. He took his wife on one arm and his daughter Susy on the other, and followed the chief inspector, who had spun on his heel and marched out into the main room. Along with the rest of those in the bedroom, I went with him, curious to see what the detective had discovered. I noticed, though, that McPhee and his wife exchanged a glance that to my eyes suggested quiet resignation to whatever the search had turned up.

Coming into the main room, I found it impossible not to glance at the couch where Dr. Parkhurst’s body lay. To my relief, someone had found a large bedspread and draped it over the body. Even so, I found a macabre urge to peek at the huddled mass under the covering, imagining its posture and terrible expression . . .

“Now, the lot of you stand here while I go into that outer room for a moment,” said Chief Inspector Lestrade, once we were all there in the main room. “Only this time, you’ll have the lights on and the door open.”

He strode through the door, and a moment later we heard a distinct rap from the vicinity of the table. “How’s that?” crowed Lestrade. “Here’s another!” And sure enough, there came another rap, just as predicted, from a different corner of the room.

Mr. Clemens strolled over to the doorway and looked through at the policeman. Behind him, I could see the faces of Detective Coleman and Mrs. Parkhurst, looking out at us. “Do that again, if you don’t mind,” my employer said. A pair of loud raps followed. Mr. Clemens turned and looked back at us, a mischievous smile on his face. “Well, Ed, I think I know why you had to leave the room after the lights went out,” he said.

“Let’s see what this one does,” came Lestrade’s voice, followed by the muffled ringing of a bell. “Oho, a regular orchestra we have here. But that’s not even the best part of it. Watch here, ladies and gentlemen.”

I was not quite certain where he meant, but it quickly became evident as a small oval picture on the wall swung quietly to one side, and Lestrade’s face could be plainly seen peering out the opening. “Here’s where your shot was fired from,” said Lestrade. “You’ll notice it’s in a direct line with the chair the victim sat in. An easy shot, especially if you’ve lined it up in advance.”

“That’s all well and good,” said Slippery Ed, who stepped forward, ignoring Martha McPhee’s hand on his elbow. “But I was in that room the whole time, and didn’t nobody come in and shoot that fellow. I’d have seen him, sure as you’re born.”

“Perhaps you should look in a mirror,” said Lestrade. “By your own admission, you were in this room when the shots had to have been fired. What’s more, you were in a perfect position to make loud noises just at the right time to prevent the shot’s being heard.”

“Hey, I didn’t shoot nobody,” said McPhee, a hurt expression on his face. “I never even seen the poor man before this very evening, ain’t that right, Martha?”

“What I’d like to know is, where did he put the gun?” demanded Cedric Villiers, strutting over to Lestrade. “There lies Dr. Parkhurst with a bullet through his head, so there must have been a gun. And yet, after searching the place from top to bottom, you’ve found no murder weapon. You haven’t a notion where it is, do you?”

“Not yet,” Lestrade admitted. “That’s a detail, but we’re good at piecing together details. This scoundrel may have had time to take the gun outside for disposal. Or—”

Whatever he was going to propose, he was interrupted by the opening of the outer door to admit a man I recognized as the one who’d been with McPhee on the doorstep when we’d arrived. “Hello, where’s Mr. McPhee?” he asked, his voice somewhat slurred. Then his eyes took in the constable’s uniform, and they opened wide for a brief moment before he turned and we heard his boots pounding as he beat a hasty retreat down the stairway. Constable Wilkins was after him in a flash, and I heard the constable’s whistle blow as he thundered down the stairs.

“There’s your answer, Villiers,” crowed Lestrade, turning to the astonished dandy. “McPhee’s accomplice took his gun away right after the shooting—by now, he’s pitched it in the Thames, or stowed it somewhere for future devilment, just as like.”

“A smashing bit of luck, what?” said Sir Denis DeCoursey, rubbing his hands. “You practically called your shot!”

“There’s still something I don’t understand,” said Mr. Clemens. “Why the hell would that man come back here, if he’d just taken away the murder weapon?”

“Your common criminal is a pitiful sort, at best,” said Lestrade, with an air of confidence. “Low mentality—you could see it written all over that man’s face. That’s why the criminal always returns to the scene of his crime, like a moth to a burning candle.”

“Maybe so, but you’ve missed the point,” said Mr. Clemens. “If he’s the one that ditched the gun, he knew what it was used for, and he’d make himself scarce around here. If he absolutely had to come back afterwards, he’d have been ready for the cops to be here. He’d have had a bulletproof alibi all ready, and a face as innocent as any choirboy. But the way he bolted just now, he didn’t have the faintest glimmer that he’d be walking into a roomful of constables and detectives—if he did, I’ll buy every man in Scotland Yard a drink.”

The chief inspector grimaced. “You’d lose that bet, or my name’s not Lestrade,” he said. “We’ll learn the whole story when Wilkins fetches him back for questioning. But I don’t think there’s any more reason to detain you all—Coleman will note down your names and addresses, and we can come by tomorrow or next day to record your statements. It’s as plain as the nose on your face, this fellow here pulled the trigger.” He pointed triumphantly at Slippery Ed McPhee.

There was a stunned silence. Every eye in the room turned toward McPhee, and those nearest him took a step back—so that where we had all been bunched together, there was now an open circle around Mr. and Mrs. McPhee.

“You wait a cotton-pickin’ minute, Mr. Scotland Yard,” said McPhee. He took a step toward Lestrade, his fist raised. Then Martha, her face grim, touched her husband on the arm, and he regained his composure. “I ain’t never pulled the trigger on a living soul,” he said firmly, “and you can take that to the bank. You ask Sam here—killin’ ain’t Ed McPhee’s style, no sir, and any man who says different is a bald-faced liar.”

Mr. Clemens rubbed his chin, then nodded. “I’ll grant him that much, Lestrade. Don’t get me wrong, now—I wouldn’t lend Ed two cents if he gave me the keys to the mint for collateral. But I don’t believe he’s got it in him to shoot a man.”

“If you’d spent as many years as I have at the Yard, you’d not be so quick to think you know what a man’s got in him,” said Lestrade, shaking his head.

“That may be true,” said McPhee, “but I never laid eyes on that poor doctor before this very night. I swear, I never shot him.” Suddenly I realized that as he spoke he had been edging closer to the half-open door out of the apartment.

Lestrade stepped forward and laid a hand on McPhee’s shoulder. “You’ll need to do better than that, Mr. McPhee. You had the means and the opportunity, and if you didn’t pull the trigger yourself, I wager you know the man who did.”

McPhee shook off the hand and turned suddenly toward the exit, but Sergeant Coleman had taken up a position between him and the door, and he seized McPhee unceremoniously by the arm, twisting it behind his back. “Be still now,” he said. “I must advise you that anything you say may be taken down and used against you in court.”

“You go ahead and do that, see if I care,” said McPhee, struggling. “You won’t find a single thing that’ll stick to me. As for Terry, he was just out having a couple of drinks, is all. He’s no more the accomplice than I am the killer.”

“His running away would seem to argue otherwise,” said Cedric Villiers. “Why flee so precipitously if he had nothing to worry about?”

“Well, from what I hear tell, over in this country an Irishman starts off with one foot in the hole,” said McPhee, staring Villiers in the eye. “Same as the colored back home. I guess Terry figured it was smarter to find out what the cops were after before he let ’em get their paws on him. I might have done the same, in his shoes.” McPhee sounded defiant, but it was easy to see that he was shaken.

“A lot of good it’ll do him,” said Lestrade. “Wilkins will fetch him back forthwith, and he’ll have the worse time of it for his efforts. Aha, I’ll wager that’s them now.”

Sure enough, the sound of footsteps came from the stairway. We all turned to look, but even before they reached the landing, we could tell that only one person was climbing the stairs. “I’m right sorry, sir. The rogue gave me the slip in the fog,” said a sour-faced Constable Wilkins, coming through the door. “I went over to the station to start the hue and cry, and then came back to lend an ’and ’ere.”

“I knew Terry was a spry one,” said McPhee, with something like pride in his voice. “Much as I wish he was here to back me up, I’m glad he’s still free. He’ll have a chance to get his wits about him before he tells his tale.”

“We’ll have the hue and cry on him before he’s gone a mile,” said Lestrade, his jaw jutting out. “Meanwhile, Constable, I’ll ask you to place Mr. McPhee under guard. We’ll take the names and addresses of these other ladies and gentlemen, and then we can let them go to their homes. We’ve got our murderer, or his right-hand man. We’ll know which it is once we’ve had a little talk down at the station.”

“You ain’t got nobody!” bawled McPhee. “I’m an innocent man, for once!”

“So say you,” said the chief inspector, with a superior smile. “So say they all. But the Detective Branch will learn the truth, or my name’s not Lestrade!”