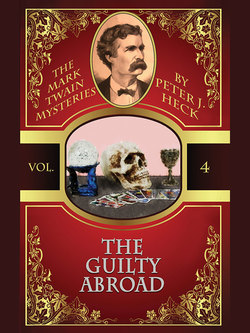

Читать книгу The Guilty Abroad: The Mark Twain Mysteries #4 - Peter J. Heck - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Historical Note and Acknowledgments

ОглавлениеThe historical Samuel L. Clemens, on whom my fictional detective is broadly modeled, lost his fortune in the early 1890s. After a series of bad investments—capped by the failure of the Paige typesetting machine, an unsuccessful rival of the Linotype—he was nearly bankrupt. He moved his family to Europe to economize, and spent much of the latter part of his life abroad, earning money to repay his debts by touring and lecturing. Thus it seems natural to take him to Europe for an adventure or two. I have chosen 23 Tedworth Square, in which he lived a few years after the nominal date of this adventure, as the home base for his London visit.

I also wanted to show him in the context of his family, from whom his financial troubles in later years forced him to be absent more than he would have liked. I have brought the whole family together to give the girls a chance to become characters in their own right. (Those interested in Twain’s family life would be well advised to seek out Clara’s book, My Father Mark Twain, which includes many letters and photographs illuminating this part of his personality.)

Twain is viewed as one of the prototypes of modern skepticism, and many of his remarks and writings on spiritualism and other supernatural phenomena amply support this image. The account of his visit to a medium in Life on the Mississippi is characteristic of his reaction to his own time’s equivalent of “New Age” beliefs. However, at Livy’s urging, he did attend séances after Susy’s death in 1896, in hopes of communicating with her spirit. The experience seems to have done nothing to change his mind concerning supernatural claims.

Gaslight London is of course the home turf of one of the greatest of all fictional detectives, Sherlock Holmes. Twain himself was no admirer of A. Conan Doyle’s stories, going so far as to lampoon Holmes in “A Double-Barrelled Detective Story.” Still, it seemed appropriate to pay some homage to the Holmes canon in a book set not only in London, but touching one of Doyle’s own obsessions, the spiritual world. So I have borrowed Inspector Lestrade (whom I have promoted to chief inspector, in accordance with the Peter Principle). I hope his performance here is in harmony with his character as drawn by his creator.

Researching these books is always enjoyable. As before, I have borrowed many of Mark Twain’s own stories and sayings, which readers familiar with his work will recognize. The serendipity of research always turns up something amusing; this time it was the Hartford air-gun factory, which was later converted to bicycle production and may well have built the bicycle that Twain attempted to tame in his Hartford days. And I found Clara’s description of her father as a “bad, spitting gray kitten” an irresistible image.

Of course, Mark Twain never became a detective (although his skeptical attitude and sharp mind would undoubtedly have made him a good one). But, given that fictional assumption, I have tried to make his character as authentic as I can. In the process, I have accumulated far too many debts to previous Twain scholars to acknowledge in this brief space. As always, any errors or distortions of fact are my own fault. But I hope I have been able in part to capture the spirit of a writer who was one of the key influences on my own growth and outlook on the world.

Finally, special thanks are due to my wife, Jane Jewell, my first and most demanding reader, who has contributed to the improvement of this book (and of its author) at every stage.