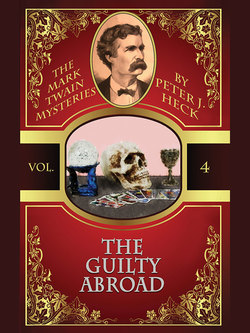

Читать книгу The Guilty Abroad: The Mark Twain Mysteries #4 - Peter J. Heck - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

5

ОглавлениеThere was a chorus of gasps and shrieks at Sir Denis DeCoursey’s announcement that Dr. Parkhurst was bleeding—and then, even as we watched, the doctor fell slowly sideways out of his chair onto the floor. Several of us were already on our feet, Mrs. Parkhurst was still in her seat, leaning sideways and imploring her husband to say something. Her sister, Miss Donning, recoiled as if in honor at the limp form on the carpet. I turned up the gas and lit it, then hurried back to the table to see what else I could do.

“Shot?” said Cedric Villiers, for once not looking bored. “How the devil could he be shot? I didn’t hear any gun go off.”

“With all that knocking and bell ringing, who could have heard it?” said Mr. Clemens, who had sat back down and put his arms around his wife and his staring daughter. He turned to look at Sir Denis DeCoursey, who was kneeling over the limp form. “Is he dead?”

“Youth!” said Mrs. Clemens, plainly shocked—at what, I wasn’t quite certain, but her use of her habitual pet name for her husband struck an incongruous note to my ears. Then, after a moment, she said quietly, “Oh. I suppose it is an appropriate question, in the circumstances.”

“He’s just barely breathing. We must try to find a doctor, though there’s not much hope with a head wound like that,” said Sir Denis, and even from across the room I was inclined to agree with his grim prognosis. With the lights up, I could see quite clearly. Too clearly; I wanted to turn my eyes away from the grisly spectacle.

“Someone help me move him to the sofa,” said Sir Denis. Cedric Villiers was closest, but he made a face, and so I stepped around the table to help. I took the legs while Sir Denis grasped the wounded man under the armpits, and between the two of us, we managed to get the limp bundle over to the nearby sofa. He was surprisingly heavy—Dr. Parkhurst had not looked that large when he had been standing on his feet. Sir Denis knelt down next to him, then looked up and said, “Someone fetch some water, and some cloths we can use as bandages. We must do whatever we can to give the poor devil a chance to live.”

Lady Alice, who had stood up almost as soon as the lights came on, nodded and went off with a purposeful look on her face, Most of the others, I noticed, were doing their best to look away. Mrs. Parkhurst had now fallen on her sister Ophelia’s shoulder and was sobbing loudly. She reached out toward her husband and cried, “Oh, help him! Someone please help him! Dear Oliver, don’t die! Don’t leave me alone!”

After a moment, Lady Alice returned with a basin of water and some towels, which Sir Denis used to swab off Dr. Parkhurst’s forehead, then to try to stanch the bleeding. After getting a closer look at the wound, he frowned and put his ear against the doctor’s chest, listening intently for a moment. His expression was grim as he straightened up and said, “I’m afraid there’s no heartbeat. May the Lord have mercy on him.”

At that, Mrs. Parkhurst began to shriek, “No, no!” Her sister wrapped her arms tighter around her, and now Hannah Boulton began to sob loudly. Mrs. Clemens and her daughter Susy both had shocked expressions, but neither seemed quite as stunned as the other ladies—of course, they had not known the victim.

Lady Alice’s face was grim, but she went and touched Martha on the shoulder. “Mrs. McPhee, is there another room where we can take Mrs. Parkhurst and the other ladies? This is a rather terrible scene, I’m afraid.”

Martha was still in her seat, blinking like a person just awakened from sound sleep. At Lady Alice’s words, she started and rose to her feet. “Yes, of course, what am I thinking of? Please, ladies, come with me. Mrs. Parkhurst, may I take your arm?”

Still sobbing loudly, Mrs. Parkhurst let herself be led through a door, apparently into a bedroom, supported by Martha on one side and by her sister, Miss Donning, on the other. The other women followed them—although Susy Clemens seemed reluctant to leave. I almost would have traded places with her, had I any good excuse to remove myself from the grisly scene. When the door closed quietly behind them, Sir Denis said, “Now we must call in a doctor—though I fear there’s little the fellow can do. And we need to inform the police.”

“Good thinking,” said Mr. Clemens. “Is there a telephone in the building?”

“I certainly wouldn’t know,” said Cedric Villiers, with a surprisingly indifferent shrug. “Ask that fellow out in the foyer—he’s the one renting the flat.”

Mr. Clemens was closest to the door; he stepped over and opened it. “Ed, you better come inside. We’re in trouble.”

“What, is the show over already?” said McPhee, getting up quickly from the red velvet-covered couch where he’d been sitting. I could see a deck of playing cards spread out on a small table in front of him—some sort of game. Apparently he had not given up cardplaying quite as completely as Martha had suggested. He took out his watch and glanced at the time. “Martha usually keeps things going a bit longer than this.”

“The show’s all over, Ed,” said Mr. Clemens, in a weary tone. “Or maybe it’s just gotten started. Somebody shot Dr. Parkhurst while the lights were out, and it looks like he’s done for. We’re going to need the police. And we might as well have a doctor, just in case.”

“Shot? Police?” McPhee’s jaw fell. “Sam, you wouldn’t pull my leg about something like that, would you? It ain’t a bit funny, and that’s the truth.” His voice had nothing of its usual jovial tone.

“I fear he’s got right of it, Mr. McPhee,” said Sir Denis, and his sober expression emphasized the truth of his words. “Here’s the poor fellow on the couch.”

McPhee stepped inside the door and took in the scene at a glance. His face turned white as he saw Dr. Parkhurst’s body on the sofa. “Jesus, it looks like he got in front of a cannon.”

“Yes, I’d say he took at least a forty-caliber round,” said Sir Denis. “Now we need to fetch the constable.”

A cagey look crossed McPhee’s face. “Look here, I don’t think we need to go bothering the cops about this little thing,” he said, trying his best to regain his usual poker face. “Poor man’s dead and gone, and can’t nobody help him, right? Seems to me we can settle things up without any big fuss.”

“It’s way too thick for that, Ed,” said Mr. Clemens, taking McPhee’s elbow. “Here’s a respectable citizen shot dead, and that’s murder in anybody’s book. You can’t just throw around a couple of bucks and make it right, as if you were caught with loaded dice in your pocket. We’re in a foreign country, and the police play by different rules. Now, is there a telephone in this building, or don’t you know the answer?”

McPhee wrinkled his brow for a moment, then brightened up and said, “Well, there ain’t no phone in here, but I seem to remember there’s one at the tobacco shop two streets over—owner lives right upstairs from the shop. I reckon he’d let me use it if I tell him how it’s an emergency. Why don’t I just go do that? I’ll only be a few minutes . . .”

“Let’s not be so hasty,” said Cedric Villiers, holding up his hand. “I don’t at all like the way this fellow acts. If we let him go, who’s to say we’ll ever lay eyes on him again?”

Mr. Clemens nodded. “I guess you’ve got a point, Villiers. If we let Ed out the door, he’s as likely to skedaddle as to go find a bobby.”

“Sam, you ought to know me better than that,” said McPhee, puffing himself up like a rooster. “Ed McPhee ain’t so low as to run off and leave little Miss Martha all by herself when trouble starts. ’Sides, I’m the only one that knows his way around this here neighborhood, It’d take anybody else twice as long as me, with all these misty dark streets.”

“What, are you daft? A yank know Chelsea as well as I?” said Cedric Villiers, sneering. “I’ll wager I could walk blindfold to this tobacconist, or anywhere else within a mile of here. But I hardly think it’s necessary to knock up the shopkeeper. There’ll be a constable out on the streets, most likely over at the corner of King’s Road.”

“I don’t doubt it,” said Sir Denis. “But consider this—we’ve got a murder on our hands, and every man in this room will undoubtedly be considered a suspect. In fact, Mr. McPhee may be the only one of us with a sound alibi—at least we know he was out of the room when the shot was fired.”

Mr. Clemens looked around at the rest of the company, his eyebrow raised in questioning, then shrugged. “Well, then, I guess Ed’s the one that has to go. But just to be on the safe side, I say we send somebody to keep an eye on him. How about Wentworth, here? He used to play football—if that old potbellied card shark tries to give him the slip, I reckon my man can run him down and put a hammerlock on him.”

“And how do we know they won’t both abscond?” said Cedric Villiers. “As Sir Denis points out, everyone in the room is a suspect. Your man has as much reason as Mr. McPhee to run away.”

“You can’t be serious,” I said. “I never saw that poor man before this evening. What reason would I have to kill him?”

“That’s for the police to determine, isn’t it?” said Villiers, fixing me with his gaze. “Your employer wanted to discredit the medium—it was obvious the minute you came in the room that you were not believers. Mr. Clemens has evidently had dealings with Mr. McPhee before, and it’s plain they are not friends.”

“That’s preposterous,” I began, but Mr. Clemens raised his hand, and I deferred to him.

“Fair enough, Villiers,” said my employer. “I know Wentworth, and I know Slippery Ed, and I know damn well which one I’d trust in a pinch. That don’t cut ice with you, and there’s no reason it should. But the sooner we get the police in here, the sooner we can all get out—the ladies in particular. My wife and daughter won’t stay the night next to a cadaver—not if I can help it, they won’t. So we’ve got to send somebody. I say we send ’em both, and get it over with.”

Neither Sir Denis nor Cedric Villiers could think of any further objection, and so McPhee and I put on our coats and hats and went down the stairs to look for a policeman, or failing that, a telephone. As we came out on the street, something occurred to me. “Where’s the other fellow who was here when we arrived—the Irishman? Did you send him home already?”

“Oh, Terry?” said McPhee. “Why, once Martha started her show, he wanted to go wet his throat. There wasn’t nothing I needed him for, so I told him to go ahead, long as he came back to straighten up when things were over. Martha usually runs just two hours, so Terry knew how much time he had. You can bet he’ll be surprised when he gets back and finds that fellow dead, and cops all over the place.” McPhee chuckled, as if amused at his assistant’s probable discomfiture. He himself seemed to have accepted the necessity of informing the police of the shooting.

“I should imagine so,” I said. “Well, if he can prove his whereabouts during the séance, he shouldn’t have much trouble with the police.” I looked around me, trying to see through the thick mist that now shrouded the streets in every direction, reducing the flickering gaslights to a nebulous glow and chilling me despite my coat and hat. It had been an eerie scene an hour earlier, when we were merely on our way to the séance, without any notion of what was about to happen. But the fog had thickened, and there was a definite sharpness in the air. After having heard the spirits’ voices, I found the atmosphere downright macabre. Add to that the shock of knowing that a man had died violently, not ten feet away from me . . . I shuddered, in spite of myself.

Then I snapped out of my reverie; action was the best antidote to this sudden fit of apprehension. “Which way are we going?”

“Let’s go thataway,” said McPhee, pointing down the street to our left. “Like that fancy boy said, the coppers usually lurk around over on King’s Road, which is the next big street. If we don’t find ’em there, we can cut back over to that tobacco shop for the telephone. And if they ain’t home, we’ll figure out which way to jump next.”

“Very well, Mr. McPhee, lead the way,” I said. After we’d gone a few paces I added, “I hope you’ll remember what you said about not leaving your wife to face the police alone.”

“Don’t worry, sonny,” said McPhee. “The days is long gone since ol’ Ed could outrun a young sprat like you. ’Sides, you know I went right out of that room after I doused the lights, so there ain’t nothing the law can pin on me, this time. I might have had something to worry about, back in my rowdy days, but I’m a reformed man. And you can go to the bank with that.”

“I certainly hope so,” I said. I meant it, too. I was undoubtedly a faster runner than McPhee, but in a fog this dense, he probably would not have much trouble if he wanted to evade me—especially if I let my attention wander. I made up my mind to keep a close eye on him. I thought the fog had gotten thicker even in the few moments we had been outdoors, and the air had certainly become colder. I buttoned up my collar, wishing I had brought a scarf with me tonight.

We came to a larger cross street, and McPhee said, “There’s usually a cop over that way”—he pointed to the left—“at least in the daytime when the shops are open, so they can confiscate an apple or a piece of cheese when they’re in the mood.” He chuckled. “I reckon that’s the first place to look.”

“Let’s hope we find him quickly,” I said. “I’m freezing out here.”

“Ah, that’s the way it always goes with the police,” said McPhee. “Smack-dab in your face when you don’t want ’em, and never there when you could use a helping hand. It’s downright aggravatin’, either way. Enough to make a fellow lose faith in the government.”

“I had no idea you had faith in government to begin with,” I said as we walked down the cobbled street. I would have preferred going a bit faster, but there was no hurrying McPhee—and I certainly did not want to get ahead of him.

McPhee laughed, with what seemed false heartiness. “That’s a good one, sonny. I guess if you hang around with ol’ Sam long enough, some of his jokes are like to rub off on you. We’ll make you into a reg’lar fellow, yet.”

I wasn’t entirely sure what sort of man McPhee considered to be a “reg’lar fellow,” let alone whether I wished to be included in that class of humanity. However, I saw no advantage in contradicting him. We walked onward through the lowering fog. At last, in the diffuse light of a street lamp, I discerned a dark-clad figure with the characteristic rounded helmet of a London bobby. “There’s our policeman,” I said, then raising my voice, “Good evening, Constable.”

“And the same to you,” said a deep voice. Under the light, I could see the figure turn to face in our direction. “ ’Ow can I ’elp you?”

“Let me do the talking,” whispered McPhee, then before I could agree or disagree, he called out in a louder voice, “Everything’s fine, just fine. But we got us a little problem we sure could use some help with.”

That hardly seemed an adequate way to characterize a murdered man in his apartment, but I said nothing for the time being. However, I made up my mind to challenge any outright misstatements of fact McPhee might make.

The policeman had walked forward to meet us, and by now we were close enough to make out his features. He was solidly built, a bit above average height, with a square, clean-shaven jaw and large dark eyes. I would have guessed his age somewhere in his thirties. “What’s the problem, then?” he said, eyeing us both up and down. “You two are Yanks, are you not?”

“You got that one right,” said McPhee, adopting the hearty manner he employed when greeting strangers. “Ed McPhee’s the name, and this here’s Mr. Wentworth, works for my old partner Mark Twain—I reckon you’ve heard of him, even in these parts.”

“Aye, that I ’ave,” said the policeman, not obviously impressed. He pointedly ignored McPhee’s proffered handshake. “Now, what can I ’elp you with? Are you two staying ’ere in Chelsea?”

McPhee rubbed his hands together. “So we are, so we are, but that ain’t the problem—in fact, that ain’t no kind of problem at all. Awful nice place, as far as I can see, and I been all over the world, to Mexico and everyplace. But the problem is, I have some folks up to my place for a sort of meeting, quality folks, you understand, Mr. Mark Twain and Sir Denis DeCoursey and all. Well, one of ’ems took mighty sick. I reckon you ought to come take a look.”

“Sick, eh? Well, I’d think you’d want a doctor for that, not a constable.”

“Why, the fellow’s a doctor himself—or was one, I guess is the right way to put it,” said McPhee. I wondered how long it was going to take him to admit that Dr. Parkhurst was dead, let alone that he’d apparently been murdered.

“Was one?” said the policeman, lifting his eyebrows. “Just what is that supposed to mean, now?”

“Well, it seems as if the fellow had a little accident . . .” McPhee began. I could stand his equivocation no longer.

“The doctor is dead,” I said bluntly. “In fact, we believe he’s been murdered.”

“Murdered, is it?” Now the policeman took a definite interest. “Now, I expect we’ll go and ’ave a look at that. Just where did you say this murder was?”

“The place is right off Old Church Street there,” said McPhee, pointing back the way we’d come. He gave me an exasperated look, as if to reprimand me for telling the truth before he was ready to let it all out, but I paid him no heed. The policeman needed to know what he was getting into.

“You wait right ’ere,” said the policeman, in a voice that made it clear he was not issuing an idle request. He grasped the whistle hanging on a lanyard around his neck and blew three sharp blasts. From some distance away came a response—two whistle blasts, a pause, and then two more. The policeman nodded and said, “Right, then. There’ll be one of the lads along in short order. We’ll wait ’ere for ’im.”

Sure enough, in perhaps two minutes, another policeman came into view, walking briskly and swinging his truncheon. “What’s the word, Albert?” he said as he saw his fellow.

“ ’Ullo, Charles. These two tell me there’s a dead man in Old Church Street, apt to be a murder,” said the first policeman. “What address did you say?”

Before McPhee could answer I gave him the number. “The second-story flat, in the back.”

“There you ’ave it. Tell the station I’m going with these two American gentlemen to see what’s ’appened,” said Albert, indicating us with his hand. “ ’Ave ’em send me a lad or two to ’elp sort it all out. They’ll want to send over a doctor, too, in case the bloke’s still breathing.”

“Aye, that they will,” said Charles. “I’ll report straightaway. Best be sharp, lad—if it’s murder, like as not you’ll be seeing the chief inspector this night.” He nodded, turned, and walked off into the fog.

“Well, gentlemen, that’s done. Now, let’s go see what the story’s all about,” said the policeman. We turned and started the short trek back to McPhee’s apartment through the chilly fog.

McPhee kept up a line of irrelevant banter the entire way. “I’m mighty glad we found you as quick as we did,” he said to the policeman. “Sir Denis and his lady, and Mark Twain—he’s my old pal from the river, known him for years—they said, ‘Ed, we’re in a heap of trouble, and no doubt about it.’ And I told ’em, ‘Don’t you worry, boys, I’ll fetch a bobby in and he’ll get straight to the bottom of this mess.’ And so I done it, just like I said I would. Any help you need to figure things out, Ed McPhee’s your man.” For his part, the policeman greeted this obvious attempt to curry favor with the silence it deserved.

We reached our destination soon enough. Cold and damp as it was, I almost wished I could stay outside rather than go back into that room and look at the lifeless body sprawled upon the sofa. But, to judge by my previous encounters with the police, we were in for a long interrogation. Probably even the ladies would be put to the question—even if none of them were suspects, they were certainly witnesses. Although none of us could have seen much in the pitch darkness of that sitting . . .

I wondered how long it would be before I could get back to my warm bed, and whether I would have any luck getting to sleep at all that night. Then I remembered that one of the group who had begun the sitting would not be sleeping in his own bed tonight. Poor Dr. Parkhurst was well beyond any thoughts of warmth and comfort, and I suddenly felt guilty wanting them for myself.