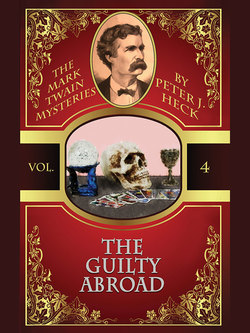

Читать книгу The Guilty Abroad: The Mark Twain Mysteries #4 - Peter J. Heck - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3

ОглавлениеThe next day, Mr. Clemens remembered some correspondence he needed to attend to, and so my plans to go back into the city had to be postponed. I briefly wondered whether I was being punished for bringing home McPhee and his wife, but if so, Mr. Clemens was punishing himself as well, since he spent the entire morning away from his beloved family, dictating letters. After luncheon, his wife handed him a thick sheaf of typewriter paper—chapters from his latest book, marked with her comments and emendations—for him to revise. We sat together the whole afternoon in his little office at the head of the stairs, he working at the typewriter (which he had brought all the way from America) and I turning my hastily scribbled notes into finished letters for him to sign and dispatch to various parties all over the world.

It was perhaps four o’clock when Mr. Clemens tore a sheet of paper out of the typewriter, put it on the growing pile of finished copy, and pushed back his chair with the air of a man who has finished his work for the day. I kept on writing—I needed only a few lines to complete the letter I was working on. He watched me for perhaps two minutes until he saw me reach for the blotter, and then he said, “Well, Wentworth, what do you make of McPhee’s séance? Is it just one more of his damned swindles?”

I looked over to try to read his expression, but he was concentrating on loading one of his pipes. “I can’t judge for certain,” I said. “I suppose we’ll all know better tonight, after we’ve seen it.”

“Oh, I wouldn’t be so sure of that,” said Mr. Clemens. “Do you remember how Slippery Ed took your money at three-card monte? You knew there was some kind of trick to it, and you were keeping your eyes on him the whole time, and he still managed to sneak in the stinger. That old rascal has about as many principles as a snapping turtle. He’d cheat himself if he could figure out a way to make a profit on it. Hell, he’d probably do it anyway, just to stay in practice.”

“I suppose you’re right,” I admitted, blushing at the memory of how easily McPhee had deceived me. “But he’s not charging us admission, and he has given his promise not to use your name in publicity. I don’t see how he gains any advantage.”

Mr. Clemens snorted and waved his hand, strewing the rug with a small spray of loose tobacco from the still unlit pipe. “You don’t think he’s likely to keep that promise for five minutes, do you?”

“You don’t?” I asked, surprised. “Then why did you accept it?”

My employer finished tamping down the remaining tobacco and looked for a match. “Because Livy and Susy want to see the damned séance. Did you see that little girl’s face light up? What kind of father could tell her no? Mark my words, though: if McPhee tries anything crooked, I’ll lambaste him as a fraud and an outrage, and publish it for the whole world to see. And if he’s lied to me, it’ll give me the moral high ground. If you want to get a reader on your side, there’s nothing that’ll do it faster than the righteous indignation of an innocent, trusting man who’s been lied to. But if people think you go around looking for trouble, they pay you a lot less mind.”

“I can understand that,” I said, nodding. Then a thought occurred to me. “Do you mean to say you’re not going to McPhee’s séance with the intention of exposing him?”

He chuckled. “Even if I did, do you think it would make much difference? Old Barnum was right, you know. It doesn’t matter how many suckers you wise up—the swindler just has to walk down to the next corner, and there’ll be another one along by the time he plants his feet. No, I just think of it as gathering material I might be able to use sometime. And there’s always the tiny chance that some of what goes on won’t be a sham—that’s the part I’m really curious about—though it’s the last thing I’d expect.”

“I’d have thought that voodoo ceremony we saw in New Orleans would be enough to convince you,” I said, remembering a hot night on the shores of Bayou St. John, with Eulalie Echo dancing to wild drum music, and spine-tingling voices echoing in the dark.

“Nobody who’s met Eulalie Echo is likely to call her a sham,” said Mr. Clemens. The pipe was finally lit, and the aromatic fumes began to fill the room as he puffed on it. “For one thing, I think she’s absolutely sincere in what she believes. I’d guess the ceremony we saw that night was made up—not the real thing at all. The point was to scare the murderer into confessing, not to get in touch with the voodoo spirits. But if there’s any case to be made for supernatural powers, I’d pick Eulalie Echo as the best evidence I’ve seen for it.”

“Then why couldn’t Martha McPhee have genuine powers?” I asked.

“Ah, now we get to the nub of it,” said Mr. Clemens. “You still want to believe in that girl, don’t you? Even after you found out she’d lured you into Ed’s game—even after you found out she was secretly married to him.”

“I wouldn’t put it quite that way—” I began, but he cut me off with a wave of his hand.

“We could argue about that all day long and get nowhere,” he said. “She is pretty—and that smile of hers is mighty persuasive. But best we both go in tonight with open eyes and as few preconceptions as we can manage—we’ll have plenty of time afterwards to argue about what we see. Promise me you’ll keep a sharp lookout, and do your best to remember everything you see and hear—not just the parts meant to impress you. I know you’ve got a good memory, Wentworth, and I’ll trust you to use it to full advantage. Between the two of us—and Livy and Susy, too; they’ve both got good heads on their shoulders—we’ve got a respectable chance of spotting any shenanigans. After we get home, we’ll compare notes and find out what we think happened.”

“Fair enough,” I said.

Mr. Clemens rose to his feet. “Good, then let’s go have a drink before dinner. I’ve gotten as much done as I’m likely to, and you look like you’re ready for a break, too.”

Neither Mr. Clemens nor I said any more about the séance, but inevitably, the subject came up over dinner. Clara, the Clemenses’ second daughter, had been in something of a sulk all through the meal, shoving her food around her plate, and saying very little, even when directly addressed. Finally her father put down his coffee cup with a loud rattle and said to her point-blank, “Clara, what the blazes is the matter with you? I know the English can’t cook worth beans, but there’s something else bothering you, or I’m a half-shaved monkey.”

“Nothing’s wrong, Papa,” muttered Clara, peering down at her half-eaten beefsteak with a martyred expression.

“She wants to go to the séance, and so do I!” said little Jean, at twelve years old the youngest of the three Clemens sisters. “It’s not fair that Susy gets to go and we don’t!”

“Why, Mr. McPhee only offered us four admissions,” said their mother, in a reasonable tone.

“He’d have let all of us in if you’d asked,” insisted Jean. “I bet he’d let us in even if we just showed up, without asking.”

“I’m certain it’s not suitable for young ladies of your age,” said Mrs. Clemens. “We’ll tell you everything that happens, you know. You and Clara can play games and have much more fun than we will, sitting in the dark in a cold English house.”

“Besides, there’ll be nothing to see,” said Mr. Clemens, gruffly. “It’s all a sham—everything Slippery Ed does is a sham and an imposition.”

“You took us to see Barnum’s circus, and you said that was a sham, and we had a good time,” said Jean, shaking her finger at her father. She turned and shot an accusing look at me, sitting next to Clara. “Mr. Cabot is going, and he’s not even part of the family.”

“Wentworth is going because I think a strong young fellow with a level head is good to have around when you’re dealing with a perpetual fraud like McPhee,” said Mr. Clemens. “I’ve heard tell of séances where the spooks tried to steal the ladies’ purses, and something like that is right in McPhee’s line. If I’d had the last word, we wouldn’t be going at all. I’ve never heard of a spirit that could tell you anything worth the trouble of walking across the street to hear.”

“Mama doesn’t think it’s a fraud,” said Clara, quietly. This caused an awkward moment, for it was true—and a significant bone of contention between her parents.

“I have not made up my mind yet, Clara,” said Mrs. Clemens. “Mr. McPhee may be questionable, but his wife appears to be an intelligent woman of some culture, and I think she may be sincere. It would be wonderful if they could really help us communicate with the spirits of those who have gone before us. If Mrs. McPhee is genuine, I should think everyone would want to know what she has to bring us. And if she and her husband are the frauds your father believes them to be, perhaps we will learn what their tricks are—and then expose them so that others won’t be injured by them.”

“It’s still not fair,” said Jean, sinking back into her chair.

“I’ll tell you what,” said Mr. Clemens, resting his chin on his steepled fingertips. “If you and Clara have questions you want to ask the spooks—”

“Why do you keep calling them spooks?” demanded Jean. “You wouldn’t call them that if you took them seriously.”

“Papa doesn’t take anything seriously,” said Susy Clemens, drawing a chuckle from her father and knowing smiles from her sisters. “Nonetheless, I think he has a good idea,” she continued. “You and Clara can tell me your questions, and I’ll be sure to ask them—and bring you the answers. And that way Papa can spend his time watching out for Slippery Ed’s tricks, instead of trying to remember your questions—or what the spirits say.”

“It won’t be the same as going ourselves,” said Clara.

“No, but it’s the best offer you’re going to get,” said Mrs. Clemens, in a tone that made it clear that there was nothing more to be gained by arguing the point. She looked up at the clock on the mantelpiece. “We’ve got just over an hour before we have to leave, so you girls decide what you want Susy to ask. We don’t want your father to keep the spirits waiting—it would be terrible if they were cross at him, and wouldn’t say anything!” At that we all laughed, and went off to ready ourselves for the evening.

We arrived at the address McPhee had given us a little before the hour of nine. It was a chilly, damp evening, and there was a fine mist beginning to descend, diffusing the glow of the gaslights along the way. Exactly the sort of evening one should be going to see ghosts, I thought to myself. A large, well-appointed brougham was in front of the building just as our driver pulled his horses over. A sharp-featured man stood on the curb beside it, reaching up his hand to assist a lady out. Another woman stood beside him, holding an umbrella. “Well, it looks like the rest of the suckers are on time,” said Mr. Clemens, in a loud voice.

“Hush, Youth!” said Mrs. Clemens, jabbing him with an elbow. “I can’t change what you believe, but I wish you would be careful what you say in front of the others. Some of the people here tonight may be grieving over a recent loss.”

“All the more reason to warn them before Slippery Ed starts his swindle rolling,” growled Mr. Clemens, but I could see that he was chastened—at least for the moment.

I alighted from the carriage and helped the two ladies out. The trio that had arrived before us had already gone up the step to knock at the door, and so just as Mr. Clemens came out of the carriage, the door to the building flew open, and McPhee’s hearty voice rang out. “Welcome, folks! Come right in.” Then, after a brief pause: “Hey, Sam—glad you could make it. Welcome, ladies—I guess that’s the whole crew here, now.”

Inside, McPhee led us and the other fresh arrivals up a flight of stairs to a second-floor apartment, where a tough-looking fellow with his cap tilted over one eye stood beside the door, as if on guard. McPhee clapped him on the shoulder and said, “I reckon this is the whole bunch, Terry. If anybody else shows up, don’t let ’em in without my say-so.”

“Right-o, Mr. McPhee,” said Terry, with a heavy Irish brogue.

“Mr. McPhee, is it? You’re coming up in the world, Ed,” said Mr. Clemens.

McPhee turned and laughed. “Good ol’ Sam—always ready with a joke! Come on inside, folks, and Miss Martha will introduce you all to each other.”

“Don’t give your right name,” Mr. Clemens said to me in an exaggerated stage whisper that brought a glare from his wife and a giggle from Susy.

McPhee steered us into a modestly furnished foyer, where he helped us hang our coats and hats in the closet. We then went through an inner door into a roomy, very decently appointed parlor dominated by a large round table. The gaslights above the fireplace were burning brightly, and there were watercolors of rural landscapes hanging on the wall. The room seemed warm and pleasant, even though there was no fire burning. The curtains were drawn closed.

In one corner was a large wooden table with several chairs around it, and several objects on its bare surface: three silver candlesticks, metal-rimmed spectacles, a large brooch, and several books—presumably objects belonging to loved ones whose spirits might be summoned. But on the whole, I thought the room looked far too ordinary to become a sort of annex to the next world. Had I come there for a social call instead of for a séance, I would have considered it a cheerful place indeed, though not really an elegant one. Martha McPhee was already there, of course, along with four others—two gentlemen and two ladies.

“Good evening, Mr. Clemens—I’m so pleased you were able to join us,” said Mrs. McPhee, coming forward to greet us. She was wearing a very plain white dress that effectively set off her dark hair and bright eyes.

“Mrs. McPhee, you’ve found a very pleasant place,” said Mrs. Clemens, leaning on her husband’s arm. She suffered from a weak heart, and I knew it had taken an effort for her to climb the stairs, but she managed a bright smile. “Do you and your husband live here, or is this just your business address?”

“Oh, this is our home for the time being,” said Martha. “We were lucky to find such a comfortable place, and in what we hear is a very good neighborhood. I’ll show you around, later, if you wish. But please, have a seat.”

She turned to the others who had arrived with us. “You must be Dr. Parkhurst,” she said to the sharp-featured gentleman, who replied with a nod and a grunt, and then she turned to face the rest of us. “Let me introduce you all—I assume no one objects? Very well, as you all know, I am Martha McPhee . . .”

Dr. Oliver Parkhurst was evidently a distinguished London physician, and looked every bit the part—respectably dressed, with dark hair just beginning to go gray, and the sort of face that suggested insight and intelligence despite his gruff manner. He had come with his wife, Cornelia, a stout middle-aged woman with an anxious expression. The other lady with them was her younger sister, Ophelia Donning, a spinster. Her hair was golden blonde, and she carried herself like a born aristocrat. I would have guessed her age at no more than thirty-five. Either she was considerably younger than Mrs. Parkhurst, or one of the sisters did not look her age. All three of them were dressed in conservative good taste, in keeping with their stations in life.

Sir Denis DeCoursey was a tall, white-haired gentleman with broad shoulders and piercing blue eyes. He wore a small, immaculately trimmed tuft of beard under his lower lip, and his well-worn blazer was a shocking bright red. He spoke with an almost incomprehensible drawl. He was the baronet of whom McPhee had spoken, and he evidently had inherited very substantial properties somewhere in Kent. His wife, Lady Alice, was a tiny little white-haired thing with a high-pitched voice, full of energy. She was wearing a shoddy nondescript dress and a hat that must have been new at some point, though perhaps not in my lifetime. Had I passed her on the street, I might have taken her for a poor parson’s wife. I was surprised—here were a real English baronet and his lady, and they were far less fastidious in their dress and appearance than a London doctor and his family!

The other man—pale, thin, and elegantly dressed, with a pale blue flower on his lapel—introduced himself as Cedric Villiers: poet, sculptor, musician, and all-around genius, to hear him describe himself. His hair was somewhat longer than the fashion, and swept straight back from his bulging forehead. He seemed only a few years older than I, and I wondered how he had managed to accumulate so many accomplishments in such a short time—if indeed he had! He sat toying with a thin ebony cane, its head carved to resemble some sort of fantastic serpent. He gazed out at the world with an annoyed expression, and barely condescended to glance up to greet us.

The last member of the group was Hannah Boulton, a woman just past middle age, dressed in heavy mourning; as we later learned, her husband had died not quite a year since. Her face was partly concealed by her veil, but it showed evidence that she must have been quite a beauty in her youth. Both the material and the cut of her dress were of the highest quality.

Of course, once Mr. Clemens introduced himself, he was the object of everyone else’s curiosity. As always with a new group, he spent a few minutes “in character” as Mark Twain, entertaining the others with a few amusing remarks. It seemed to be a sort of professional obligation, though he never acted as if he minded it. The others seemed pleased to have such a famous man among them—with the possible exception of Cedric Villiers, who merely looked bored. That was apparently all the current fashion among British geniuses, since he did his best to maintain that appearance for most of the evening.

Perhaps inevitably, after Mr. Clemens had made a few remarks on general subjects, Sir Denis leaned forward and said, “I say, Clemens, it’s quite a surprise to see you here. I’ve read some of your books, and I’d have thought you’d not be all that keen on spirits and the other world, eh?”

“Well, I can keep an open mind about the spirits,” said Mr. Clemens, leaning against the mantelpiece. “I can’t say I’ve ever heard anything about the other world that made it sound very appealing. If the spirits are talking to us from Heaven, I reckon I’ll see what I can do to get to the other place.”

“Papa!” said Susy, feigning shock, and Mrs. Boulton appeared genuinely shocked. But Sir Denis gave a deep chuckle, and even Villiers’s face betrayed a brief flicker of interest.

“There you go with your jokes, Sam,” said McPhee, who had been bustling about the room, arranging chairs while Martha handled the introductions. I had tried to watch what he was doing, but it was difficult to keep an eye on him and still pay polite attention to the others as they introduced themselves. McPhee continued with a smile that seemed a bit forced. “Just you wait till you hear Miss Martha’s spirits. I reckon they’ll change your mind, if anything can.”

“I’m from Missouri, Ed,” said Mr. Clemens, shoving his hands into his pockets. “But I’ll tell you before we start, I took all my money out of my wallet before we came here, so there’s no point trying to steal it.”

McPhee laughed again, and Mrs. Clemens gave her husband an icy stare, which he pretended not to notice—though he evidently decided not to pursue the subject any further. As for Martha McPhee, her expression of wounded dignity spoke volumes. Slippery Ed’s nervous laughter faded into an uncomfortable silence.

Stepping forward, Martha McPhee said, “Now that we all know one another, why don’t we begin our sitting?” She walked over to the large round table and rested her hand lightly on the back of one of the chairs. “Please take any seat you wish—it doesn’t seem to make any difference to the spirits.”

“What if I wanted that one?” asked Mr. Clemens, pointing to the chair Mrs. McPhee had her hand on.

She smiled patiently, like a teacher confronting a stubborn schoolboy, and stepped away from the chair. “Why, of course, Mr. Clemens. Would you like to search under the table or have me roll up my sleeves, as well?”

Mr. Clemens had clearly not expected this response, for he muttered, “Oh, I reckon any old chair will do,” and took the one nearest to him.

Martha McPhee smiled again, and stepped forward to the same chair as before. “Come, now, I believe we are all ready. Edward, when everyone is seated, will you see to the lights? And then I’ll ask you to retire to the outer room to guard the door. We have exactly twelve in our circle, and anyone else would bring the total to thirteen. So please make certain no one intrudes until we are done here.”

“It figures Ed would be the unlucky thirteenth,” said Mr. Clemens, under his breath. But he took his place at the table, and the rest of the group seated themselves, as well. His wife sat to his left, Susy on his right, and I chose the seat between Susy and Martha. After a few moments of shuffling chairs, everyone was in their places, and McPhee began to turn off the gas. As the last flame went out, we found ourselves in darkness, and we heard McPhee cross the room and open the door; a brief shaft of light came in from the foyer, and then he closed the door behind him, leaving us in the dark—waiting for whatever spirits chose to come.