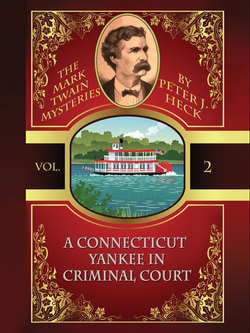

Читать книгу A Connecticut Yankee in Criminal Court: The Mark Twain Mysteries #2 - Peter J. Heck - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4

Оглавление“Do you really intend to embroil yourself in this murder case?” I asked Mr. Clemens. He was strolling at his usual leisurely pace (as I forced myself not to rush ahead) along Orleans Street, away from the river in the direction of the Parish Prison.

Detective LeJeune had arranged for my employer to visit the Parish Prison that afternoon, and to spend half an hour talking to a certain prisoner: Leonard Galloway, the cook accused of murdering John David Robinson. Somewhat to my surprise, Mr. Clemens had accepted the invitation without hesitation.

Mr. Cable, obviously pleased at how quickly events were moving, offered to accompany us to see the prison. At that, Mr. Clemens shook his head. “No, George, I have to do this one by myself—well, I’ll want Wentworth to come along. But the point is for me to make up my own mind. It’ll be hard enough to keep the cook from saying what he thinks I want to hear, without having somebody there he’s known since he was a boy to complicate things. I promise I’ll tell you everything when I get back.” Mr. Cable reluctantly admitted that Mr. Clemens’s objections were well-founded, and we left him and LeJeune sitting over their coffee.

“I still haven’t decided what I’m going to do, Wentworth,” said Mr. Clemens now. “George Cable believes that Galloway is an innocent man; it’s damned near an article of faith with him. But George has been away from New Orleans for ten years, and a man can change a lot in that much time, especially if you figure that the cook couldn’t have been much older than twenty then. And that’s ten years of being told over and over again that he’s less than a real man, and having his nose rubbed in it by every white man he meets.” We paused a moment at the corner of Bourbon Street as a fully laden beer wagon rumbled past, the big horses straining at the traces, headed for some saloon.

We crossed the dusty street and Mr. Clemens continued. “That’s why I don’t want to jump into the case just on Cable’s say-so, Wentworth. Is Leonard Galloway a convenient victim chosen to appease the public, or is he a poisoner? If he really is a murderer, and I lend my name to the battle to defend him, who does it help? It doesn’t help the blacks, it doesn’t help Cable, it doesn’t help the people of New Orleans, and it sure doesn’t help me. So I want to be sure I know what kind of man Galloway is, and the best way I know to decide that is to talk to him. I can tell more about a man in five minutes of talking to him, face-to-face, than in a year of hearing what other people say about him. So here’s a chance to talk to him and see what I can learn.

“Besides, this is as good a chance as I’ll ever have to get a look around the old Parish Prison. It’s a New Orleans landmark in a dismal sort of way, on the order of the Bastille. It dates from before I was born, and there are a lot of strange stories about it. They’ve finally decided to build a new prison up on Tulane Avenue, and tear the old one down. So this is probably my last chance to see the inside of the place. I imagine I’m unlikely to see it as an overnight guest, now that I’m supposedly an honest citizen.”

“I should hope not!” I said, shocked at the notion of my employer spending a night in prison. Perhaps respected authors of mature years were still imprisoned in Russia, or other barbaric places with no constitution, but I could not imagine Mr. Clemens being jailed. Well, perhaps it might have happened in the bygone era of debtor’s prisons—but hardly in these enlightened times.

We walked up Orleans Street to the corner of Tremé, where we found a grim-looking structure, three stories high and covering an entire city block. We presented ourselves at the entrance, where the policeman on duty instantly recognized “Mark Twain,” and waved us through the doors where many wretches undoubtedly met a much less congenial welcome and entered with far less hope of a timely exit than we experienced.

Even at first glance it was clear that the building sadly needed repair—better yet, replacement. One of the senior keepers, Mr. DeBusschere, appointed himself our guide and led us into the heart of the ancient dungeon.

Mr. DeBusschere was a thick, muscular man with a full white mustache and a clean-shaven head. He wore a blue uniform with a holstered pistol at the waist, along with a large ring of keys. He was obviously impressed at the chance to escort a world-famous author, and so he took us on a roundabout route, giving us a full commentary on all the sights and history of the Parish Prison, smiling broadly all the time, although the smile stopped short of his eyes. Mr. Clemens looked at everything with lively interest, and so I refrained from expressing my annoyance that we were not taken directly to see the cook.

Mr. DeBusschere put great emphasis on the lynching of the Italians accused of shooting the police chief a few years earlier; his theme appeared to be the valiant but unsuccessful efforts of the guards (himself prominent among them) to protect the prisoners. “Here’s Cell Number Two, where six of the Italians hid the night the lynch mob came,” he said. “We left the dagos free to run inside the prison, hoping they’d have a chance to save themselves, but the citizens followed them down that way into the courtyard—we’ll see that in a little while—and shot them down.”

I peered into the gloomy cell, lit by a single gas flame from the hall where we stood. Several prisoners stared back, with no sign of recognizing their distinguished visitor. “What a terrible place! It must be a very hotbed of vermin and disease,” I said.

“Well, we have the very answer for that,” said Mr. DeBusschere, proudly. He pointed to the ceiling with a sweeping gesture. “We let the bats nest in the rafters undisturbed so they can kill off the flies and mosquitos. That’s a sure preventative to yellow fever, you know.” I peered into the dark, but could not make out anything. Still, the notion of bats swooping down over the poor souls in the cells sent a chill up my back.

“Yes, and Cable tells me they fumigated the place back in ’82,” said Mr. Clemens, conversationally. “They took out over a hundred barrels full of dead rats.”

“Well, that’s what the newspapers claimed, but it’s an exaggeration,” said the keeper. “I was here at the time, and I doubt there were more than ninety-five barrels. But good riddance to the filthy vermin, says I.” He rattled his keys self-importantly and led us on to the next section of the prison. I resisted the temptation to ask whether the place had been given a proper cleaning since.

Mr. DeBusschere took us through several different sections of the prison, pointing out places he thought we might find interesting: a doghouse where two of the arrested Italians had hidden and escaped the mob; bullet holes in the wall where two others had been found and shot to death; and the infamous sweatbox that, until very recently, had been used to coerce recalcitrant prisoners to confess. At every turn, prisoners crowded forward, some of them pleading pathetically, asking for their lawyers, for food, for their wives or mothers. A few of them tried to beckon me over to the bars, but Mr. DeBusschere had warned me not to listen to such invitations. “I can’t guarantee your safety,” he said. Still, my indignation grew to see such inhumane and uncivilized treatment, even of murderers and thieves, let alone the unfortunates whose only crimes were mental deficiency or lunacy, but who were indiscriminately thrown in with the worst kind of hardened criminal.

I think our guide must have detected my revulsion at the barbaric conditions prevailing within the prison, for at last he took us up a stairway to a different section of the building. “Now, I don’t want you to think we don’t know how to treat decent folks who somehow fall afoul of the law,” he said. Much to my surprise, we found ourselves surrounded by cells far cleaner and more roomy than those we had just seen.

We entered a large common room with comfortable chairs and writing tables and curtains concealing the bars on the windows. A couple of guards stood casually by the door, conversing with the prisoners as if they were the best of friends. The inmates here were far better fed and dressed than their fellows in the cells we had just left. Mr. DeBusschere told us that they were even allowed to order dinner sent in from restaurants in the neighboring community. One fellow was being measured for a suit of clothes, and another, a stout man with long stringy hair combed upward across his skull in a futile attempt to cover a large bald spot, recognized Mr. Clemens and had the audacity to walk over and offer him a cigar. “You’ll find this as good a smoke as you’ll get this side of Cuba,” he told him. Mr. Clemens stared at the fellow, but took the cigar and put it in his breast pocket, politely thanking the prisoner.

After a short while in this comparatively comfortable section of the prison, we headed for the courtyard where we would meet Leonard Galloway, the cook arrested for Robinson’s murder. “Who was that rascal who gave me the cigar?” asked Mr. Clemens, as we came down the stairs.

“Adolf Mueller,” said Mr. DeBusschere. “He’s a precinct worker in the Fourth Ward. He beat up a policeman who went to question him about extorting money from a house over on Customhouse Street, and the cop pressed charges. The madam and the girls were too scared to testify, but the cop wouldn’t be scared off or bought off, and neither would the judge. Now Adolf’s doing ninety days in the Orleans Hotel,” the prison guard concluded, chuckling. Upon hearing this, Mr. Clemens took the cigar out of his pocket and sniffed the wrapper with an expression that combined evident relish and profound regret. Then, as we passed an open window, he flung it through the bars.

“Waste of a good cigar,” said Mr. DeBusschere, with a surprised look on his face.

“Damned good cigar, unless my nose has failed me in my old age,” said Mr. Clemens. “But somebody else is bound to find it before it gets rained on, and I hope he’ll enjoy it more than I ever could have, once I knew what kind of son of a bitch gave it to me.”

Mr. DeBusschere brought us down a rickety flight of stairs to a large courtyard, surrounded on all sides by the prison buildings and walls. Along one side, three tiers of rounded arches created a pleasant contrast to the stark purpose of the building. Prisoners of all races and nationalities filled the courtyard, although they tended to stay in groups with their own kind. Some chatted animatedly with their fellows, while others simply paced or sat dejectedly against a wall, out of the direct rays of the hot afternoon sun. Among the latter was a dark-skinned man who did not even look up at our approach, until Mr. DeBusschere prodded him and said, “Leonard, there’s a man here to see you.”

The man looked up, squinting into the sun, and rose quickly to his feet. “Excuse me, mister, but aren’t you Mr. Mark Twain?” he said to my employer. His voice was a deep baritone with the soft inflections I’d come to associate with the New Orleans accent.

“That’s who he is, and he wants to ask you some questions, so mind your manners,” said the keeper, in a gruffer voice than he’d used speaking to Mr. Clemens or me.

“That’s who I am, and this is my secretary, Wentworth Cabot,” said Mr. Clemens, extending his hand. “George Cable heard about your case, and asked me to come see you. Is there any chance Leonard and I can speak some in private?” he asked, turning to Mr. DeBusschere.

The keeper grumbled a bit about regulations, but the complaints were evidently strictly pro forma. Mr. Clemens took something out of his pocket and slipped it into DeBusschere’s hand, and the smile returned to the keeper’s face. He quickly ushered us into an unoccupied cell just off the courtyard. “I can let you talk for twenty minutes. There’ll be a keeper in earshot if the boy causes any trouble,” he told Mr. Clemens. “But I think Leonard knows that he’ll get back any trouble he starts, with compound interest. Ain’t that right, Leonard?”

“Yessir, Mr. DeBusschere,” said the Negro with a frightened look. Evidently satisfied, the keeper nodded to Mr. Clemens and left, pulling the barred door shut behind him.

I looked around and saw that we were in a clean, sparsely furnished room, perhaps six by eight feet, with a small, high, barred window that let in the bright southern sun from the courtyard. There was a small bench bolted to the wall beneath the window. “Sit down and relax, if you can,” said Mr. Clemens, waving in the direction of the bench. The Negro took the seat, still looking warily toward the door through which the keeper had left. There was nobody within sight, but anyone could have stood around the nearest corner and overheard all we said.

I took the opportunity to observe Galloway more closely: he was a bit over average height, possibly five feet eleven inches, and solidly built, although not with the kind of bulky muscle that comes from heavy manual labor. His skin was a rich chocolate color, and his hair was cut short. His clothes were not expensive, but they were relatively new and clean, despite his overnight stay in prison. I guessed his age at about thirty, judging by his unlined face and trim waist. At present, he looked thoroughly miserable.

“I remember you, now that I can get a look at you,” said Mr. Clemens. “I saw you in the kitchen a couple of times when I last visited George Cable in New Orleans. Ten, maybe twelve years ago, if I’m not mistaken.”

“Yessir, that’s right,” said Galloway. “I ’member you, too. ’Course, I was just a boy, and you was a writer, a friend of Mr. George’s.”

“Well, there’s the difference between us. I’m still a writer, but you’re hardly a boy these days. Cable tells me you’ve become a mighty good cook.”

Galloway gave a little smile. “Thank Mr. George for saying that about me. I learnt how to cook from my old Aunt Tillie, right in his kitchen. I sure do miss them days.” And then, the memory of where he was seemed to strike home, and he slumped forward and his gaze dropped to the floor. I felt immediate sympathy for his plight. But was I looking at an innocent man or a cold-blooded killer? I couldn’t tell, and I wondered how Mr. Clemens meant to spot the difference.

“We’ve all seen better days, Leonard. But I’ve come here on business, and that keeper will be back soon enough, so let’s get down to it while we have the time. The police say you murdered Robinson, and Cable says you couldn’t have. I know Cable, and I put a lot of faith in his word. So I’d like to believe you’re innocent, and see you back in your own home. But I’m not the judge, and not about to become one. What can you tell me that might help me get you out of this place?” He leaned casually against the wall, his eyes fixed on the prisoner.

“I don’t know,” said Galloway, wringing his hands. “I told the police everything, ’cause I don’t have nothing to hide. I told ’em all I didn’t put poison in Mr. Robinson’s food. I’d be crazy to try that. I’d be the first man they come looking for. If I done it, you know I’d have gone and lit out for Texas. I sure wouldn’t be catching a nap on my front porch when they come looking for me. Not after it was in all the newspapers he was poisoned.”

Mr. Clemens pointed his finger at the prisoner. “They say he yelled at you because you were drunk on the job. Fined you a day’s pay and sent you home.”

Galloway hung his head. “He did, and I deserved it. Me and a few other people on the block was at a funeral the day before, and stayed up late consoling the widow—and joining in the singing, and having a few drinks. The next day I had a bad headache, so I figured a little hair of the dog that bit me was the answer. And I ’spect I had a little too much of that hair, ’cause I fell asleep in the kitchen. Mr. Robinson found me and cussed me out and sent me home to sober up without my pay.” He paused, as if gathering his thoughts, then shook his head and looked up with a rueful expression.

“Yeah, I was mad when I went home, even though I knew better. But Mr. Robinson came out to the kitchen looking for me the next day, and he acted as if he was the one that done something wrong. Said he shouldn’t have yelled at me in front of the others, I was the best cook he ever had, and I had a job with him as long as I wanted. And he gave me the pay for the day before, even though he sent me home! I didn’t want to take it, Mr. Twain. I didn’t earn it, and I didn’t want it. But he made me take it. What kind of fool would want to go and kill a man that treated him like that?” I could see tears on his face.

Mr. Clemens sat down next to Galloway, putting his hand on his shoulder. “A bigger fool than anybody in this room,” he said. “Or a worse monster. You’ve convinced me, Leonard. I’m going to do my best to get you out of here. But to do that, I’m afraid I’ll have to prove that somebody else is the real killer.” He stood and looked up at the window. “Do you have any idea who that could be?”

“None of the other servants, anyhow,” said the cook. “The only one in the family they didn’t like is Miz Eugenia. She’s got a real temper. It wasn’t like Mr. Robinson to yell at folks or order ’em around. That’s why I was so flabbergasted when he cussed me out. I figured it was ’cause Miz Eugenia wasn’t there, and he felt he had to do something. Maybe he was mad over something else and took it out on me, although that wasn’t his way, either.” There was the beginning of hope on Galloway’s face.

“What about the family? Visitors to the house? Were there any that you know of that day?” Mr. Clemens stopped and looked at him.

The Negro clasped his hands and lifted them to his chin, thinking deeply. At last he shrugged. “If there was, I didn’t see them. But out in the kitchen, I wouldn’t have known it, anyway, unless they called for some kind of refreshments. It was a weekday, so the mailman would have come by twice, and we got a delivery of ice just before lunchtime. But Mr. Robinson was out a good bit of the afternoon, doing business in town. After dinner, Miz Eugenia’s brother, Mr. Reynold Holt, came by as I was packing up to leave. I don’t know how late he stayed, though, or if anybody else came later on. Arthur, the butler, might could tell you.”

“Write down those names, Wentworth, the butler and the brother-in-law,” said Mr. Clemens. He paced a few steps across the cell, and I took out my notebook. “I’ll have to see if I can talk to the butler. But think, Leonard. Did you hear any talk among the servants that might suggest why someone would want Robinson dead? Did he have any enemies?” Mr. Clemens’s mind seemed to be moving at high speed, although as usual he spoke and walked as if there were all the time in the world.

Galloway shook his head. “If he had any enemies, they sure never came to dinner at the house. But he was always talking politics, always politics—who going to run for mayor, how to clean up the Quarter, what to do about the Mafia—this and that and the other thing. There was loud arguments sometimes, ’cause I could hear ’em from the kitchen, but they didn’t sound like the kind of thing to kill a man for. They’d laugh as much as they argued.”

“Who’s they?” said Mr. Clemens. “Was it family, businesspeople, old friends? Think hard, Leonard, this could be important.”

“Mostly the same few folks. Mr. Reynold Holt, old Dr. Soupape, Mr. Dupree the lawyer, Mr. Percy Staunton, Professor Maddox, and their wives . . . some family, some friends from way back. Mr. Robinson was in the army with some of ’em, during the war. They weren’t the only guests, but they were the regulars.” Galloway moved forward on the bench, arching his back as if to stretch sore muscles.

But Mr. Clemens was not done yet. He leaned over him and continued with his questions. “Were there any family quarrels you heard about?”

“Sure, that’s what family’s like, ain’t it? But nothing really hot or nasty, that I heard. Me and my brother Charley get into worse fights all the time. Some of the live-in servants might know more, though. You ought to talk to them. Go and see Arthur. Or that girl Theresa, Miz Eugenia’s maid. Tell ’em I said to tell you what they know. They’ll talk to you.”

“Get those names, too, Wentworth,” said Mr. Clemens, but I was already scribbling them into my notebook. I finished the list and had my pencil poised for Mr. Clemens’s next question, when a knock at the door announced the return of Mr. DeBusschere.

“Well,” said the keeper, “looks like y’all had a nice little talk. Sorry to rush you, but Leonard’s got to get back to his own cell.” His hands were on his hips, and the keys dangled by his waist. Behind him, I could see the sunlit courtyard and the other prisoners.

The hope I’d seen on Leonard Galloway’s face had disappeared again. The cook rose from the bench and, without being ordered, walked toward the door. But as he passed Mr. Clemens, he paused for a moment and said in a low voice, “I sure do ’predate you coming to see me, Mr. Twain. It do mean a lot to me, even if nothing comes of it.”

“Come along, now,” said Mr. DeBusschere. “You know you shouldn’t waste Mr. Twain’s time.”

“Just one thing more, can I please, Mr. Keeper?” said Galloway. DeBusschere nodded, and the cook said, “Get word to my Aunt Tillie, over at my place on First Street. Tell her you saw me, and I’m all right. That you’re gonna help me, if you can.”

“I will,” said Mr. Clemens, and Galloway nodded, evidently satisfied. I put my notebook in my pocket and stepped out into the sun. Mr. Clemens and the cook were right behind me. My employer turned and shook hands with our guide. “Thank you for the tour, Mr. DeBusschere,” he said. “You’ve given me a lot of good stories to put in my new book, and I’ll make sure to give you credit for them.”

DeBusschere beamed, and it was clear he was already planning how he would tell his family and friends about escorting the famous author around the old prison house, and maybe even getting into a book. As he escorted us to the front door, Mr. Clemens turned and said, as if in an afterthought, “I’m glad you were able to let us talk to Galloway awhile. Take good care of him, now. I think he’ll be going home sooner than you expect.”

“We try to take good care of all our guests,” said the keeper with a chuckle that wasn’t entirely pleasant to my ears. “Y’all come back sometime, and we’ll do the same for you.”

Mr. Clemens laughed heartily at this sally, although I myself saw nothing humorous about it. “There are some who might think I belong here,” he said, “but I reckon I’ll just have to disappoint them. Good day, Mr. DeBusschere.” Thus we took our leave of the Parish Prison. I can think of very few places I have been gladder to walk away from.