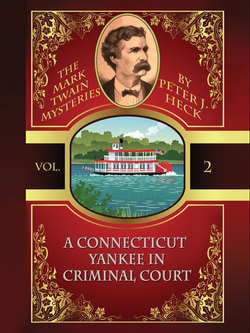

Читать книгу A Connecticut Yankee in Criminal Court: The Mark Twain Mysteries #2 - Peter J. Heck - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

ОглавлениеMy instructors at Yale always spoke confidently of preparing their students for life. I believe that, in general, they did their job well. Upon my graduation, I felt I had learned many things, both practical and theoretical, and had gone out to confront the world confident of my abilities and my training. But as I soon realized, nothing could have prepared me for the position of traveling secretary to Mr. Samuel L. Clemens—or, to use the name by which most of the world appeared to know him and his writings, Mark Twain.

What could have prepared me for a lecture tour that began with a murder in New York City and reached its climax (although not its conclusion) with the recovery of ten thousand dollars in buried gold? Along the way, I had survived a dunking in the Mississippi, tested my wits and skill against riverboat gamblers, and fought two strenuous battles with a backwoods bully. Somehow, through it all, I had also managed to perform my secretarial duties to Mr. Clemens’s satisfaction, and after traveling nearly the whole length of the river, we came at last to New Orleans.

Mr. Clemens had known New Orleans well in his days as a steamboat pilot but, since then, the great national upheavals of the Civil War and Reconstruction had altered many things in the city. He himself was now a world-famous author, lecturer, and traveler who had seen the great cities of Europe as well as traveled extensively throughout America, and his face was apparently as familiar to the man in the street as that of the President of the United States. But despite these far-reaching alterations in himself and in New Orleans, Mr. Clemens claimed that it remained the most singular city in the world.

It was our first morning in the city. We were waiting in the Café du Monde, an establishment that sits open to the sidewalk in the old section of the city, also known as the French Quarter. Our waiter had just brought us a plate of beignets (a sweet local pastry), and I was sipping one of the best cups of coffee I had ever tasted. George Washington Cable, a local writer with whom Mr. Clemens had shared a lecture tour some years before, was to join us for breakfast and an informal tour of the city.

Mr. Clemens puffed on a cigar and scanned the bustling crowds in nearby Jackson Square, beyond which I could see the impressive Roman Catholic cathedral. I sat there in silence, trying to absorb the sights, sounds, and smells of a city that might as well have been on some other continent. Even the light seemed to have a different quality from that of my hometown of New London, Connecticut. From down the way came the sounds of a thriving market, with vendors calling out their wares in French patois, Italian, and an English more melodious and liquid than any I had encountered in my travels thus far.

Finally Mr. Clemens said, “Here he comes.” I looked up to see a diminutive fellow, with a full dark beard and a suit of somewhat old-fashioned cut, bustling across the street. “George, you old humbug, it’s good to see you. I’d like to introduce my secretary, Wentworth Cabot. He went to Yale and played football, but it doesn’t seem to have hurt him any.”

The little man laughed and reached up to shake my hand, with a bright smile that was a marked contrast to his sober dress and demeanor, then sat down at the table. After ordering his own café au lait and another portion of beignets, Mr. Cable inquired about our trip downriver. With no further urging, Mr. Clemens embarked on a highly colored account of the voyage we had just undertaken. With considerable relish, he recounted how he had unraveled two murders, ending with our finding ten thousand dollars in hidden gold in an abandoned livery stable. “You should have been there, George,” he said. “There’s no feeling in the world like sticking your hand into a dark hole, not knowing what’s waiting for you—maybe a snake, maybe nothing at all—and pulling it out, full of double eagles. Although standing up on a stage in front of a whole boatload of people and pointing my finger at a murderer was a pretty close second. That came close to trumping anything I’ve ever done on a stage.”

“Having seen you in front of an audience, I call that a remarkable statement,” said Mr. Cable. His voice was soft, with the distinctive accent of New Orleans. “But from what you’ve said, solving the murder couldn’t have been very hard. There were only a few people on board who could have been guilty, and it must have been more or less obvious once you looked in the right place.”

Mr. Clemens blew a ring of cigar smoke before replying to the other writer. “Obvious enough once it’s explained, but I’m the only one who saw it, George, and there were plenty of other people looking for the answer. I was under considerable pressure because I had pretty good reason to think the killer was going to come after me, once we got to the place where the treasure was hidden. Some people say that personal danger helps focus a man’s mind, but in my experience, it’s a lot more likely to scare him out of his wits. So, all things taken into account, I think I did a pretty good job as a detective.” He took a bite of his beignet, carefully brushed the powdered sugar off his mustache, and then continued.

“I’ve always scoffed at these Pinkertons and would-be Sherlocks, but that was before I tried my own hand at it. There’s a knack to detection that not everybody has. I’ve always said that piloting taught me how to look at a set of facts and see what’s behind them, and of course, being a writer gives you a pretty good sense of people’s character. If I were setting up in life again and had to pick a career, I could see myself trying out the detective business, with someone like Wentworth here to do the legwork for me.”

“Perhaps you could make a career of it,” said our host. He sipped his coffee, a contemplative look on his face. “But you have to admit that the affair on the riverboat was very unusual. You had a limited number of suspects and a clear motive—child’s play, compared to the usual run of unsolved murders. Besides, you were practically born on a riverboat. You’d have a much harder time of it in a city like New York or New Orleans, where you don’t know the lay of the land so well.”

“Harder still would be making a living at it,” said Mr. Clemens. “I saw my share of murder investigations when I was writing for the newspapers. Nineteen times out of twenty, there’s nothing mysterious about a murder: it’s a couple of drunken bullies arguing over a woman or a domestic quarrel that gets out of hand. Everybody knows who did it. All the police have to do is arrest him. Half the time, the murderer confesses right on the spot. Not much work for a detective there.”

Mr. Cable put down his coffee cup and leaned back in his chair. “That’s true enough,” he said, after a pause. “And the unsolved ones are usually where some poor fellow tried to resist an armed robber, or where a hardened criminal eliminated a business rival, as it were. Unless there’s an eyewitness, the police have no place to start. Again, there’s not much chance anyone will hire a detective to help solve it.”

“That doesn’t leave much room for the Sherlock to make a living, does it?” said Mr. Clemens, shaking his head. “Either the answer is obvious from the beginning, or there’s no evidence and no incentive for the police to go digging for the answers. It’s only when the victim has important friends that they do much more than go through the motions of investigating. If that’s one case out of five hundred, I’d be surprised.”

“Curiously enough, there’s just such a case right here in New Orleans,” said Mr. Cable. “I’ve been following it in the local newspapers. John David Robinson, who was being talked about as a candidate for mayor next election, was found dead in his bed almost two weeks ago. Robinson was in the pink of health, so the family doctor asked the coroner to do an autopsy, and it turned out he’d been poisoned. If he’d been some no-account fellow off the street, they’d probably have written it off as stroke or maybe bad whisky and put him in Lafayette Cemetery without a second thought.”

“Have the police arrested anyone?” Mr. Clemens leaned forward, his eyes lighting up.

“No,” said Mr. Cable, shaking his head. “No arrests so far, although the police claim they’re closing in on a suspect. But I think that’s just the usual blarney, meant to make them look as if they’re making progress on the case. Reading between the lines of the newspaper stories, I think they’re baffled.”

“Poison’s supposed to be a woman’s weapon,” I said, recalling something I’d read in a history book. “Wasn’t it one of the Medicis who used it so much?”

“All of the Medicis, if you can believe the stories,” said Mr. Clemens. “I doubt we can blame them for this one, though.”

Mr. Cable made a wry face. “Not that the police wouldn’t jump at a chance to blame them, if there were any to be found. When the New Orleans police can’t find anybody else to arrest, they’re likely to claim the Mafia is involved and arrest some convenient Italian.”

“Failing that, they’ll blame some mysterious outsider that nobody ever manages to locate,” said Mr. Clemens. “Of course, there’s a skeleton or two in everybody’s closet, and they’re likely to come tumbling out in a murder investigation.”

“Yes, and there’s many a juicy story hidden behind those stately doors out in the Garden District,” said Mr. Cable. “Now, here’s your opportunity to play detective, Clemens. A genuine mystery, the police at an impasse, and a wealthy family to make it worth your while. It’s exactly the kind of case where you could prove you have the knack.” The little man’s eyes twinkled over the rim of his coffee cup as he took another sip.

“Well, so it appears,” said Mr. Clemens, “but I suspect the answer’s easier to find than the newspapers make it out to be. You were a reporter, George. You know as well as I do that the point of the job is to sell newspapers, and the best way to do that is to create a sensation. And nothing’s more sensational than murder in high places. I’d lay you odds that when the dust settles, this’ll turn out to be a household accident—the poor fellow mistook rat poison for headache powder, or something of the sort. Next most likely is that his wife learned that he was seeing another woman and put arsenic in his soup.”

“That would be quite a surprise,” said Mr. Cable. “John David Robinson was the epitome of respectable New Orleans society, spoken of very highly by everyone who knew him. Which makes it even more an enigma why anyone would want to kill him. Doesn’t that pique your interest, Sam? Here you were, telling me how you’d solved two murders and recovered a hidden treasure on your boat ride down here, and talking as if solving mysteries was the easiest thing in the world. Why don’t you tackle this one, then? Are you worried that you’ll fall short of your boasting?”

“Now, George, stop pulling my leg,” said Mr. Clemens. “Even if I were in the detective business, which I’m not, I’d never get my foot in the door without the family’s help. Unless someone in the family thinks the police aren’t doing their job, why would they let some outsider paw through their dirty linen? And you can be sure the police will make this case a top priority. They know which side their bread is buttered on. I’ll grant you the story is interesting enough, but I can’t see any profit in poking my nose into it. Besides, I’m here on important business of my own. No time for me to go hunting for mysteries to solve.”

Mr. Cable smiled. “I should have known you’d find some excuse to squirm out of it, Sam. Don’t tell me about setting up as a detective anymore! Here I bring you a delicious murder case, full of dark secrets and whimsical characters, and you won’t even rise to the bait.”

Mr. Clemens shook his head stubbornly, and Mr. Cable continued. “But if you’re not inclined to take the case, I suppose we’ll have to read about it in the newspapers and speculate about the parts they can’t print.”

“I’ll content myself with that,” said Mr. Clemens agreeably. “I have a book to write and plenty of good stories to fill it with. The police can go about their business with no fear of competition from Mark Twain.”

“But we poor authors have to sit, quaking in our boots, knowing that our next book will be in competition with Mark Twain,” said Mr. Cable with a chuckle. “Perhaps I should persuade you to go unravel this murder and rush to get my next book to press while you’re preoccupied!”

“Well, if you’re writing a novel, you needn’t worry,” said Mr. Clemens. He waved his hand dismissively, although I could see that he was pleased by his fellow writer’s compliment. “I’m up to my ears just writing down the story of this latest trip down the river. The truth has always done better for me than anything I can dream up.”

“Do you expect anyone who knows you to believe that?” said Mr. Cable, laughing. “Your books may not always be strictly fiction, but that says nothing whatsoever about their relation to the truth. Why, there are more lies in your nonfiction than in all your novels put together.”

“That’s the way it should be,” said Mr. Clemens. “Why should a man go to all the trouble of writing a novel if he was just going to fill it up with lies?”