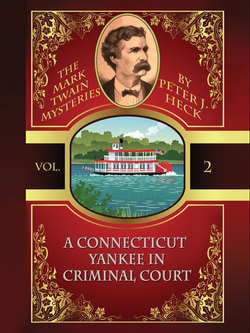

Читать книгу A Connecticut Yankee in Criminal Court: The Mark Twain Mysteries #2 - Peter J. Heck - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

7

ОглавлениеThe next morning was Saturday. Despite our having eaten a late and rather rich supper after our arrival back in the French Quarter, Mr. Clemens was up and about bright and early, full of enthusiasm about his chosen task of clearing Leonard Galloway of an apparently unjust murder charge. After his usual hearty breakfast—beefsteak, fried eggs, and strong coffee, not to forget the morning dram of whisky he took “on general principles”—we returned to our rooms. There we found a message from Mr. Cable, who had evidently made good use of his time after parting from us the previous evening.

“George has gone right to work,” said Mr. Clemens. He tore open the envelope and nodded as he read, then turned to me. “The Lafayette Literary Society is giving a literary luncheon this very afternoon, and they’ve just learned of my visit to this fair city—thanks to George, no doubt—and would be honored and delighted to have me as their guest, blah blah blah. Of course, they’ll expect me to say a few words after the meal, but that’s no great imposition. The important thing, from our point of view, is that Mrs. Maria Staunton—the sister of Mrs. Robinson—will be present.”

“Capital!” I said. “With any luck, we may even be seated at the same table with her.”

Mr. Clemens shook his head. “The invitation is for me, I’m afraid. I could probably push them to find room for you, but what’s the point? You’ll have to stay here in any case, to get the message we’re expecting from the hoodoo woman.”

“Yes, I’d forgotten about that,” I said, sinking into a chair. “Bolden will be coming to see us, so I suppose I have to stay here.”

My disappointment must have shown in my face, for Mr. Clemens put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Don’t feel slighted, Wentworth. It’ll be a deadly dull literary luncheon, like hundreds of others I’ve been to: soporific speeches and self-congratulating literary talk by people who have less right than an Arkansas mule to an opinion on literature. I suppose the food will be good enough—this is New Orleans, after all—although the company will probably take the edge off my appetite. But I doubt I’ll learn one thing of consequence about our murder case. All I can really hope to accomplish today is to wangle an invitation to Mrs. Staunton’s home, and I’ll be certain to get you included on that. I’ll want you along when we meet the whole family, since they’re our main suspects.”

“I suppose I’ll have to settle for that,” I said. “What answer shall I give to the hoodoo woman—what was her name again?”

“Eulalie Echo,” said Mr. Clemens. “Assuming that’s her real name, not that it matters. Bolden says that everyone in the Garden District confides in her, so she could be our ace in the hole if she’s willing to help us. Tell Bolden, or whoever comes to speak for her, that I’m out. You’ll give me the message, and I’ll answer directly when I’m back, although I can’t say how long that’ll be. George may want to talk about the case for a while after our luncheon. If Eulalie wants to talk with me, find out when’s a good time for her. I can’t think what else she might say. As long as she wants to help us free Leonard, I’m willing to work with her on any reasonable terms. Use your judgment, but don’t put me out on a limb.”

“Very well,” I said. “I won’t make any promises for you. I assume even a hoodoo woman can be reasonable.”

“I certainly hope so,” said Mr. Clemens. “It’s not what people usually want from witches and fortune-tellers, but I’m sure she’s capable of it when it’s to her advantage.”

Around 10:30, Mr. Clemens left for the Garden District, where he would meet Mr. Cable and go with him to the literary luncheon. I spent some time on his business correspondence, then wrote a long letter to my parents back in New London. I walked out to post the letters, then lunched at a little gumbo shop just down the street from our pension, having left word where I was to be found in case someone came looking for me. Strange as the local cooking had seemed to me at first, with its unpredictable mixture of ingredients and hot seasoning, I was becoming accustomed to it—nay, actually taking a liking to it. Besides, a cool glass of lager went a long way to counteract the red-hot pepper.

After lunch, I was feeling lazy after the morning’s work, and so, upon returning to our pension, I went down to the breezy courtyard with a cool drink and a book of stories by an English writer Mr. Clemens had recommended, a fellow named Kipling who wrote about India. The time passed pleasantly, in a tropical setting of potted ferns and a tall palm tree silhouetted against a square of bright blue sky, much as I imagined the skies of the Mediterranean to appear. Thus I spent the better part of the afternoon until our landlady (Mme. Bechet, a diminutive Creole woman reputedly of ancient family and impeccable pedigree) appeared to announce a visitor for Mr. Clemens. I looked at my watch and was surprised to see that it was nearly four o’clock.

“Well, Mr. Clemens is out, but I can talk to the fellow,” I said. “Did he give his name?”

“Ah, m’sieur, he had no card. It is a colored boy with a suitcase. I told him to wait at the back door,” she said. “Do you wish to receive him ’ere?”

“Why, it must be Buddy Bolden,” I said. “Mr. Clemens and I are expecting him. Send him in, if you please.”

The visitor was indeed Buddy Bolden, dressed in a good suit and carrying what looked like a miniature piece of luggage; I wondered where he might be traveling. “Hello, Buddy,” I said. “Mr. Clemens had an unexpected appointment and won’t be back until later—possibly not until after dinner. But come, sit down, tell me what the news is. Mme. Bechet will bring you something to drink. I could use another one, too.”

Buddy looked over at Mme. Bechet, who gave an audible sniff. “M’sieur, I can bring you a drink, but I am not in the habit of waiting on servants and messengers.”

“It don’t matter,” Bolden said, with a shrug of his shoulders. “I just have a message to give, and then I’ll go.”

“Oh, bother,” I said, remembering what part of the country I was in. “At least come on up to my room, so we can talk in private. After you’ve gone, Mme. Bechet can decide whether she wants to fumigate.” We climbed two flights of stairs and closed the door behind us. There were two chairs in the little room, and I waved toward them. Bolden put his case on the floor and sat in the one nearer the window. “It may be beneath the landlady’s dignity to fix you a drink, but if you’d like to wet your throat, Mr. Clemens won’t miss a drop or two of his whisky, and I don’t mind pouring it,” I said.

“That sounds good,” he said, smiling for the first time.

I went through the connecting door to Mr. Clemens’s rooms, and returned with the whisky and soda bottle and poured us two drinks. When I’d given him his glass, and we’d both taken a sip, he said, “You got to understand about these Creole ladies. She’s got her pride, and she’s got her French name. Her grandma may have been as black as mine, but that don’t count, in her mind.”

“I suppose you’re right,” I said. “But I don’t have to like it.”

“What the hell, mister, I like it a lot less than you do, but ain’t nothing I can do about it, ’cept maybe have a drink and laugh about it.”

“I suppose you’re right,” I said. As boorish as Mme. Bechet had been, I had to admit that some of my friends at Yale were little better in their treatment of the lower classes. But there was nothing to be gained by harping on it, and so I brought the subject back to our business. “What news do you have for us? What does Eulalie Echo have to say?”

Bolden looked me in the eye, sizing me up with disconcerting frankness. After a moment, he said, “She won’t say nothing without she sees you. You and Mr. Twain, both.”

“That’s no surprise, although I can’t see what she needs to talk to me for. I’m just Mr. Clemens’s secretary, after all. But I’ll give him your message. Did she tell you a time that would be convenient? Should we make an appointment?”

“No, man,” said Bolden. “You don’t need no appointment. Miz ’Lalie don’t pay no mind to the time, least not clock time. Just go see her. She lives out at Fourth and Howard, real close to Miz Galloway.”

“That’s a curious way to arrange things,” I said. “What if we go to her place and she’s not in? Doesn’t she go out shopping or have other engagements?”

His face changed, and he glanced around him, although only the two of us were in the room, and the sky outside the windows was bright and clear. He picked up his glass and took a deep sip of the whisky. “I’ll tell you something,” he continued in a lower voice. “When me and Charley Galloway showed up at her house, it was like she knew we was coming and what we wanted. She was answering our questions before we finished asking them. I don’t put a lot of stock in spirits, but ’Lalie Echo is scary, man. There’s stuff goes on in that house of hers I don’t understand at all. You and Mr. Twain go see her, and you’ll see what I mean. And then she’ll say whatever she has to say.”

I was surprised by Bolden’s response, but I decided to reserve judgment until I had met the woman in question. “Do you think she means to help us?”

He laughed nervously. “If she didn’t, you think she’d bother to talk to you? I don’t know what she has in mind, but I don’t think she’d be wasting people’s time if she wasn’t going to help out Leonard. And that’s all any of us want, ain’t it?”

“I suppose so,” I said. “Well, I’ll tell Mr. Clemens, and he’ll decide what to do.” Then, seeing that he still appeared somewhat anxious, I changed the subject, pointing to his little suitcase sitting on the floor. “Are you traveling somewhere?”

He grinned. “No, man, that’s my comet case. There’s a dance at Odd Fellows Hall tonight, and I’m in the band.”

“Oh, that’s right. Charley Galloway said something about your comet yesterday. I thought it was a joke.”

“Well, it was, but it ain’t no joke when I play it. Charley’s in the band, too—guitar player and singer.”

“I see. Well, it sounds like good fun,” I said.

He laughed again, this time without a trace of nervousness or self-consciousness. “That ain’t the half of it. By the time the dance is over, I’ll have four or five pretty girls want to help me carry that little comet case home.” He finished his drink in one gulp, picked up the case, and stood. “Thank Mr. Twain for me. I sure do appreciate the taste of his whisky. Now I got to go. We been working on a couple of new tunes, and Charley’s having trouble learning them, so we set up an extra rehearsal before the dance. You tell Mr. Twain what I said, and go see ’Lalie. I guarantee you, we’ll get Leonard out of that jail if it takes all next week and a couple more days, too.”

“I hope it doesn’t take that long,” I said, and shook his hand. “I’m sure Leonard doesn’t want to stay there another day if he can help it.”

“Amen to that,” said Bolden, and I walked him down the stairs. As I let him out through the wrought iron door leading from the courtyard to the street, I had the feeling that unseen eyes were boring into my back. I closed the gate behind him and turned to find Mme. Bechet peering out at me through the curtains of her apartment, disapproval plainly written on her face.

Sometime after six o’clock, I went out to eat, Mr. Clemens not yet being back from the Garden District. Having seen a number of little restaurants in our walk down Decatur Street, I resolved to give them a try. The first place I walked into was full of Italians, and recalling Mr. Cable’s stories of the Mafia and knife fights, I was about to leave, but the aroma of the food changed my mind. I ended up having a succulent chicken dish, cooked with tomato sauce and herbs, with thin noodles in the same sauce on the side, and a quite passable bottle of red wine. A pair of young men, with a guitar and a mandolin, began playing about halfway through my meal, and so I was fed and entertained quite adequately. It was nearly dark by the time I returned to Royal Street to find Mr. Clemens just alighting from a carriage, driven, much to my astonishment, by none other than Henry Dodds, who tipped his hat and sang out, “How d’ye do, Sherlock!” when he spotted me.

“Good evening, Wentworth,” said my employer. “I reckon you’ve eaten. Have you heard from our friends out on First Street?”

“Yes, we have,” I said, returning the coachman’s salute. “Come on inside, and I’ll tell you the whole story.”

“Good. I have news of my own; we can swap stories,” said Mr. Clemens. He tossed the fare up to Henry Dodds, and we went upstairs.

Up in Mr. Clemens’s room, he insisted on my pouring us each a glass of whisky and soda, although I could have done without and I suspect he could have as well. Then he listened as I told him Bolden’s message from Eulalie Echo. He only interrupted once, to say “Good man!” when I mentioned giving Galloway’s neighbor a drink of whisky. When I had finished, he said, “Well, I guess we’ll have to pay Eulalie a visit. We may be spending more time out in the Garden District than here, by the time this is done. If I’d known that, I’d have had you get us rooms out there instead of down here by the river.”

“You may have to,” I said. “From the look Mme. Bechet gave me when I let Bolden out, she appears to consider me some sort of carpetbagger, or worse.”

“Sticking her nose into our business is the quickest way for her to lose it,” said Mr. Clemens. Then, seeing my expression: “Our business, Wentworth, not her nose. But let me tell you what I learned today. The Lafayette Literary Society luncheon was midway between a bore and a farce, as these things usually are. Why people who’ve never been to the moon insist on writing poetry about it is beyond me, but the woods are full of ’em. I suppose it would be too much of a challenge to them to write about something down-to-earth.

“Anyway, I met our pigeon, Mrs. Maria Holt Staunton, and a cute little bird she is, if a bit flighty. If her sister’s anything like her, I doubt she can concentrate on one thing long enough to be a credible murder suspect. One minute she’d be talking about literature, the next about spiritualism, the next about the terrible murder in her family, and the next about who knows what? I think she almost welcomed the death, in a sense, because it gives her an excuse to dress up in black and go about with a mournful expression, which becomes her more than most, although it was never my taste.

“But I screwed my courage up, and sat next to her for the better part of an hour, playing the eminent literary gentleman and managing not to laugh inappropriately. For that alone I deserve this drink, Wentworth. And by careful attention, and not especially broad hints, I managed to get us a dinner invitation for Monday night. I had to represent you as a learned gentleman and a budding literary lion in your own right, but she’ll never know the difference.”

“Excellent,” I said. “With any luck, we can parlay this into a chance to meet the entire family.”

“Oh, I expect they’ll be there,” said Mr. Clemens, taking a cigar out of his pocket. “I’ve never known a literary lady who could pass up a chance to impress her whole family when she hooks a genuine author as a dinner guest. Maria Staunton has probably spent half her life being mocked as a bookworm and bluestocking. This is her chance to prove she was right all along, Wentworth.”

“I suppose you’re right,” I said. “Meanwhile, when shall we plan on visiting Eulalie Echo?”

“We can decide that in the morning,” he said. He snipped the end of the cigar and fished around in his pockets for a match. “Aunt Tillie may have spoken to the Robinson’s butler, Arthur, by then. Possibly we can kill three birds with one stone and see them all on the same day. If not, perhaps we’ll go out and visit Eulalie Echo tomorrow.”

“There’s something strange about visiting a hoodoo woman on the sabbath, don’t you think?” I said.

Mr. Clemens found a match and struck it, then held the flame to the cigar until the pungent smoke came. When it was lit to his satisfaction, he looked up at me. “If you ask me, Wentworth, there’s something mighty strange about visiting her at all. But anybody who can get Cable’s back up the way it was the other night is someone worth meeting. If nothing else, I’ll be able to pull his leg with hoodoo stories for as long as he lives. George is one of the best writers alive, and a fine man to sit at the dinner table with, but sometimes he needs the wind taken out of his sails.” My employer chuckled. “I get the feeling that solving this murder case will be rewarding in more ways than one.”