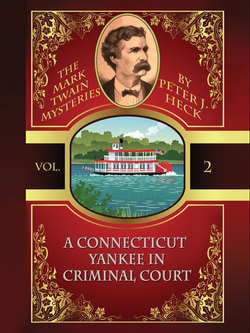

Читать книгу A Connecticut Yankee in Criminal Court: The Mark Twain Mysteries #2 - Peter J. Heck - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

6

ОглавлениеThere was a moment of silence, and then Buddy Bolden laughed. “Well, if we was going to try and bust Leonard out of jail with guns and ladders, we wouldn’t need Mr. Mark Twain to help us. Plenty of folks have ladders, and there ain’t no shortage of guns, if it came right down to that. But I reckon you could count me out, if that’s what you was planning, ’cause all you’d end up with is a bunch of colored folks being shot instead of just one being hanged. Still, I do have an idea that might work, if you don’t mind listening.”

“I sure don’t mind listening,” said Mr. Clemens. “There might be plenty of ladders around, but good ideas are in short supply just now.”

“Well,” said the young man, “we all know Leonard didn’t kill this Mr. Robinson. But that don’t seem to hold no water with the police. So what we need to do is prove who did kill him, and then getting Leonard out of prison is no problem at all. That make sense?”

“Makes plenty of sense to me,” said Mr. Clemens, nodding his head. “Keep on talking.”

“I reckon whoever killed Mr. Robinson, it has to be somebody he knew,” said Bolden. “It don’t make no sense any other way. Strangers don’t go around putting poison in each other’s food, ’specially not in big houses down in the Garden District. So whoever killed him, it was somebody he knew and trusted enough to eat or drink with.”

“Yes, we’ve been thinking the same thing ourselves,” said Mr. Cable. “A family member, or close friend, or a trusted servant would be my guess.”

Charley Galloway shook his head. “Maybe family or a friend,” he said, “but unless I miss my guess, it wasn’t no servant.” He paused, looking from Mr. Clemens to Mr. Cable, and finally at me; then, as if satisfied with what he saw in our faces, he continued. “I think the murderer has got to be a white person.”

There was a silence; then, “Charley! Watch what you say!” said Aunt Tillie, clearly apprehensive at her nephew’s statement.

“He doesn’t have to hold his tongue for my sake, Aunt Tillie,” said Mr. Clemens. “I’ve already come to pretty much that same conclusion, and I think George agrees with me. The police talk like they’ve solved the case, but I think they’re going in the face of the facts. The important question is, which one of Robinson’s friends and family is the killer?”

“Well, there’s where my idea comes in,” said Bolden. “One thing you learn pretty early, living this close to all those rich folks’ houses, is that they’ll go talking about anything in the world in front of the butler or cleaning maid, just as if there weren’t nobody listening at all. They may think they’ve got secrets, but every one of them has got a houseful of servants that know more about their secrets than they do. You know that, Miz Galloway.” He looked at the elderly woman who sat in her rocking chair, fanning herself and shaking her head. Outside the single window, the sky was turning darker, but it was still warm inside the little house.

“Well, I suppose it’s true,” said Aunt Tillie, after a pause. “But it’s one thing to hear something, and another to tell about it. One thing for sure, if you work in the white folks’ house, you best know how to keep what you hear to yourself. Maybe somebody in Mr. Robinson’s house does know who killed him, but even if they do, how you goin’ to get them to tell Mr. Twain about it?”

Bolden smiled. “That’s where my plan comes in, Miz Galloway. Maybe they won’t tell Mr. Twain about it, and maybe they won’t even tell you or me, but I reckon I know somebody they will tell. All we got to do is convince her to help us find out what we need to know, and then we can use that to help get Leonard out.”

Aunt Tillie looked at Bolden with a suspicious expression. “Who you talking about, boy? Who’s this her everybody talks to?”

“You know who he means, Aunt Tillie,” said Charley Galloway, his face lighting up with sudden comprehension. “He’s talking about Eulalie Echo.”

Aunt Tillie dropped her fan and clasped her arms over her bosom. “Lord have mercy!” she said, shaking her head. “Poor Leonard ain’t in enough trouble already that now you want to go talking to a hoodoo woman!” She picked up her fan and began to ply it vigorously.

Bolden and Charley Galloway stood there with sheepish grins, but Mr. Cable acted as if a poisonous snake had come into the room. “What a ridiculous suggestion! I know the kind of superstitious nonsense these voodooists believe. I witnessed some of their heathen rituals, back when I was writing for the Picayune. How can you expect anything useful from them?” He stood up abruptly, as if ready to bring the interview to an end.

“Hold your horses, George,” said Mr. Clemens, furrowing his brows and motioning Cable back toward his seat. “One man’s superstition is another’s simon-pure gospel. We’ve had this argument before. Let me hear Buddy’s idea before you try to convince me it’s no good. We want to prove Leonard is innocent and get him out of prison. And as long as we accomplish that, I for one don’t especially care how we do it—short of murdering somebody on our own, I suppose. Who is this hoodoo woman, and how do you think she can help us?”

The two colored men looked at each other, as if deciding who was willing to risk Mr. Cable’s wrath. At last, Charley Galloway swallowed, looking at Aunt Tillie, then turning to Mr. Clemens. “Her name’s Eulalie Echo, and she lives at Fourth and Howard, right close by. A lot of folks know her—I mean a lot of folks that works in the white people’s houses. She tells fortunes, and she gives advice, and they say she talks to spirits—”

“You mean to devils!” said Cable, with an agitated expression. I was somewhat surprised at how much the subject disturbed him. One of my friends at Yale had dabbled in spiritualism, and after dutifully attending a couple of his séances, I had no doubt that some people could talk to spirits. Whether the spirits ever said anything of interest back to them was another question entirely.

But Mr. Clemens cut Mr. Cable off with a wave of his hand and a look that threatened thunderbolts. “Let the fellow tell us what he has in mind, George. You can say your say when he’s finished, but I’m not about to have you cutting him off after every three words. And if you want to argue religion, argue it with me, on our own time. How do you think this fortune-teller can help us, Charley?”

With hooded eyes, Charley Galloway looked back and forth between Mr. Cable and my employer, as if deciding which of them it was more dangerous to displease. Mr. Clemens’s impatient expression apparently decided him, for he turned to face him and continued his explanation. “Like I explained to you, a lot of folks talks to her, and sometimes they tell her things they won’t tell anybody else. And I reckon if she asks ’em questions, they’ll give her answers they won’t give anybody else. If she knows it’s to help Leonard, maybe she’ll ask some questions about what goes on in the Robinson house—and I bet she knows somebody who’ll tell her what she wants to know.”

Mr. Clemens nodded. “That’s straightforward enough. No deals with the devil, no human sacrifices, no black magic—just asking the right questions of the right people. Do you find anything objectionable in that, George?”

Mr. Cable still looked somewhat uncomfortable, although I wasn’t sure whether it was more at the notion of dealing with a hoodoo woman or at being chastised by Mr. Clemens. But he nodded his head and said, “I suppose not, if that’s as far as it goes. The object is to help Leonard, after all.”

“That’s right,” said Mr. Clemens. “What about you, Aunt Tillie? Do you think Eulalie Echo can help us?”

Aunt Tillie rocked slowly back and forth. “Maybe,” she said, grudgingly. “Maybe she can, and maybe she can’t, and maybe she will, and maybe she won’t. What I want to know is what she’s goin’ to want us to do for her. I never did hear that she was any special friend of Leonard, to be doing him favors. And I sure can’t see her doing us no favors for free.” She began rocking harder, as if to emphasize her opinion.

“That’s a good question,” said Mr. Clemens. “We probably need to know the answer to it before we start counting on this Eulalie Echo. Buddy, you’re the one who suggested talking to her. Can you find out whether she’ll help us, and what she might want in return?”

“Sure, I’ll go see her tonight,” said Bolden.

“I’ll go with him,” said Charley Galloway. He looked at Aunt Tillie and at Mr. Cable. “And maybe some folks ought to think about just how much Leonard’s neck is worth. All I know is, if it was me sittin’ there in Parish Prison, instead of my brother, I’d be mighty unhappy to find out my friends and family was letting me go hang because they didn’t want to do business with Eulalie Echo.”

“That’s settled, then,” said Mr. Clemens, slapping his hand down on the arm of the couch. “Can one of you bring me the answer at Royal Street tomorrow?”

Charley Galloway and Bolden looked at each other, and then Bolden said, “I’ll do it. I don’t got to work until tomorrow evening, anyway. Charley’s got his barbershop to look after.”

“Good,” said Mr. Clemens. “Now, what else can we do to try to clear Leonard? Aunt Tillie, do you know the servants in the Robinson home well enough to talk to them?”

Aunt Tillie thought a moment. “Only one I know to talk to is Arthur, the butler; he goes to our church, and Leonard brought him over a few times on his day off, when they was going to go out to the lake or to the park together. Arthur acted little bit stuck up at first, but he was friendly enough by the second or third time he came by. Now he nods his head and says hello when he sees me.”

“You say you see him in church,” said Mr. Clemens. He leaned forward, closer to Aunt Tillie. “I’d appreciate it if you asked him if he’d be willing to talk to me, somewhere away from the Robinson house. Do you think he’d do that?”

“He always acted friendly with Leonard, so I think maybe he’d talk to you if he thought it could help the boy—seeing as how it’s Leonard’s own family asking,” said the woman. “Day after tomorrow’s Sunday, so I’ll see him then and ask him.”

“Good. Ask him if he’s free to come down to Royal Street to talk, the sooner the better. One more thing you may be able to help with, and then I’m out of ideas. I think Charley and Buddy are right that the killer is a white person. I think it’s even more likely that it’s one of Robinson’s family or close friends, if that’s the right word for somebody that poisoned him.”

“Poisoned him and let the poor colored man go to jail for it,” said Charley Galloway. “There’s lots of words for somebody like that, but I ain’t going to say them in Aunt Tillie’s house, ’cause she’d never let me in the door again.”

“I’ll say ’em, if you want!” said Buddy Bolden, with a sly glance toward Aunt Tillie.

“I’d wash your mouth out with soap, Charles Bolden,” said Aunt Tillie. Her voice was loud and stem, but she had a little smile on her face as she said it.

“That wouldn’t do,” said Charley Galloway, laughing. “Next thing you know, he’d be blowing bubbles through that comet of his, and wouldn’t that sound awful?” Everyone laughed, and some of the tension that had built up in the room began to dissipate.

“Maybe it wouldn’t be so loud,” said Aunt Tillie, and now her smile was bigger. “But Mr. Twain was saying something, and it ain’t polite to go talking on without letting him finish.”

Mr. Clemens was smiling at the exchange, but now his expression became serious again. “I think the murderer is one of Robinson’s acquaintances, and so it would help me solve the case if I can talk to the people he was close to: his family, his close friends, maybe his business partners, if he had any. Now, Cable says to tell them I’m writing a book. He thinks that’ll open the door and get them to talk to me. But Wentworth here thinks they’ll be shy of the publicity, especially if one of them has something to hide. Leonard must have talked to you about them. How would you suggest going about getting in to see Robinson’s family and getting them to talk to a stranger?”

“You want to go see Miz Maria Staunton, the widow Robinson’s sister,” said Aunt Tillie without even a pause for thought. “She can’t hardly walk across the room without stopping to read a book halfway, or so says Leonard. He told me he heard her sister make fun of her for reading books right at the dinner table, ’fore she married Mr. Staunton. If she won’t talk to two gentlemen writers, I’ll be mighty surprised. And if you get her on your side, she’s your way in to talk to the rest of the family.”

“That’s right; I hear she’s active in the Lafayette Literary Society,” said Mr. Cable. He jumped up from his seat and paced, evidently excited. “She writes a bit of poetry, holds literary salons, and wants to be a patron of the arts. Yes, I think she’s our ticket, Clemens. Thank you, Aunt Tillie, I should have thought of that myself.” He turned around and bowed to our hostess.

“Nothing to thank me for,” said the woman, with a serious look. “It’s Leonard’s life we’re trying to save, and anything I can do to make it easier is the least I can do.” Then her expression changed, and she pointed to the place Mr. Cable had vacated on the couch. “We been talking serious business so much I like to forgot my manners! Now, you set right back down and make yourself comfortable, Mr. Cable. Is that glass empty? Charley, get that pitcher and pour the gentlemen some more lemonade.”

When we were ready to leave, Buddy Bolden ran down to the corner to fetch our cabdriver, Henry Dodds, who drove up a few minutes later with Bolden on the seat beside him and a twinkle in his eye. “So, you wasn’t foolin’ when you said you was Mark Twain,” he said to Mr. Clemens as young Bolden jumped deftly down to the brick sidewalk. “Maybe this other gen’leman’s George Washington, after all.”

“Yes, and the tall fellow’s Abe Lincoln,” said Mr. Clemens, climbing up to the passenger seat. “With two presidents on board, you ought to give us a free ride back to the French Quarter.”

“Well, leastways I can see you ain’t George Washington,” said Henry Dodds. “Last I heard, he never told a lie, and that’s more’n I can say about somebody else here.”

“That’s not a lie, that’s artistic license,” said Mr. Cable, hoisting himself up next to Mr. Clemens. “But you’ll only have to take the two of them back to the Quarter. I’m staying down on Eighth Street, just below Coliseum. You can drop me there, then take these two gentlemen back to Royal Street.”

“Eighth and Coliseum—sho ’nuff, Mr. Washington,” said the driver, and I barely had time to seat myself before he snapped the reins and off we went, with Charley Galloway and Buddy Bolden standing on the sidewalk laughing.

We went past more of the double shotgun houses, but within a few blocks, the faces of the children playing on the street began to be predominantly white instead of the mixture of races in the neighborhood we had just left. The houses became larger and more affluent as we neared Saint Charles Avenue, and when we crossed it, we had clearly entered a very different realm. Even the children were better dressed, and the only colored faces to be seen were obviously those of servants.

Mr. Cable was staying with old friends—close to his former residence, as he told us—and there was still a fair amount of light when our driver dropped him off. Mr. Cable tossed Henry Dodds a twenty-five cent tip and suggested, “You might drive back along Prytania and point out the Robinson house—it’s at the corner of Washington. I think Mr. Clemens would be very interested in that.”

“Oho,” said Dodds, as we turned and started down the street. “Now I’m beginning to see what you folks is up to. I thought it was mighty strange you had business up where I dropped you off. That ain’t a neighborhood where a lot of white folks from out of town is likely to go visiting, if you get my meaning. But the boys down at the corner told me that was Leonard Galloway’s house you went to, and ain’t nobody in N’Orlins that ain’t heard all about how he’s in Parish Prison for poisoning Mr. Robinson.”

“You’re almost right, Henry,” said Mr. Clemens. “Leonard Galloway’s in jail, all right, but being arrested doesn’t mean he’s guilty. Never judge a man until you have all the facts.” He paused for a moment, then added, “Just maybe, we have a few facts that the police don’t have.”

“Well, I’ll be doggone!” said Henry Dodds, turning to look back at us. “I’ve been driving this old hack for twenty years, and I’ve seen just about everything you can think of, and a couple you probably can’t, but this ’bout beats it all. You sure this here tall fellow ain’t Sherlock Holmes, instead of old Abe Lincoln like you said?”

Mr. Clemens laughed. “Wentworth is a lot of things,” he said, “and a few of them have surprised even me when I found out about them. But one thing I can absolutely assure you—he isn’t Sherlock Holmes.”

I wasn’t certain how to take that statement, but just then Henry Dodds slowed his horse and pointed to our left. “That’s the Robinson house coming up, right there on the corner.”

The house in question was situated on a large corner plot and surrounded by a tall wrought iron fence. The grounds were attractively landscaped, and the house spoke of considerable affluence even for this neighborhood, where the evidence of wealth and power was plain to see. Although the sun was beginning to drop below the horizon, I could make out a two-story portico of wrought iron lacework, which stood out clearly against the pale color of the house—a light pink, or perhaps even lavender, if I could trust my sense of color in the fading light. It went entirely against all my instincts of the proper color for a home, yet somehow it was remarkably tasteful. “What a pleasant place to live!” I said.

“And just a short distance from the cemetery,” said Mr. Clemens, pointing to the stone wall we had just passed. “Very convenient, don’t you think?”