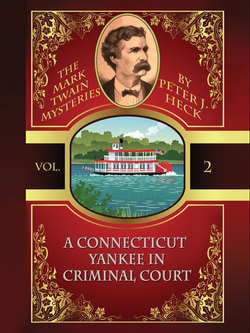

Читать книгу A Connecticut Yankee in Criminal Court: The Mark Twain Mysteries #2 - Peter J. Heck - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеMr. Clemens and I spent the rest of the morning walking about the French Quarter, with Mr. Cable acting as our native guide. He took a particular delight in pointing out details of the ornate wrought iron railings and colorful hanging plants that grace the second stories of so many otherwise ordinary buildings throughout the quarter. A common pattern in this district is for a building’s street level to be given over to commerce, while the higher stories are apartments. An eastern visitor, used to looking straight ahead of him, has constantly to be reminded to look up, else he would miss much of the charm of the city. Also, in many of the houses, elegant courtyards invisible from the street offer a cool refuge from the noise and dust of the outside world. Among the houses Mr. Cable pointed out with special affection were two on Dumaine Street and another on Royal Street that figured in his own stories.

As the oldest section of New Orleans, the French Quarter was at one time populated almost entirely by Louisiana Creoles. It was then a fashionable and affluent area of the growing city. But the Vieux Carré has in recent years fallen on hard times: many buildings showed signs of disrepair, and we heard as much Italian as French spoken in the streets. Walking down Decatur Street, not far from the riverfront, Mr. Cable told us with a wry grin that the local newspapers had renamed that section Vendetta Alley on account of the frequent assassinations in the vicinity. Only a few years before our visit, the Italian Mafia was accused of murdering the New Orleans chief of police. That had set off a terrible outbreak of violence, culminating in the lynching of nineteen Italians, who may or may not have been involved in the murder of the chief.

Still, as Mr. Cable pointed out, the majority of the new immigrants are honest people making their way by hard work, and they can soon be expected to add their characteristic national flavor to the life of the city. To judge by the bustling commerce I saw on the streets of the French Quarter, it may be only a matter of time before it is again a prosperous area. Certainly, it would be a shame for such a picturesque district to remain in neglect.

We ate lunch in a little restaurant on Chartres Street that I would hardly have noticed if Mr. Cable had not led us to it. When I asked for the bill of fare, the waiter said, “We don’t need no menu, I know what we got.” He proceeded to reel off a list of dishes, half of which I had never before heard of. Mr. Clemens noted my consternation and laughed. For his part, Mr. Cable said, “Young man, I can see you’re a newcomer to Creole cuisine. May I help you find something to your liking?”

I had been ready to order a plate of red beans and rice, that being the only item on the list of which I could guess the nature of the ingredients, but Mr. Cable’s offer opened up other possibilities. “Why, thank you,” I said. “What, pray tell, do all these odd names mean?”

“Well, a good bit of the local diet is based on seafood. We get excellent fresh fish from the Gulf, and the shellfish are mighty fine as well. For example, this place makes a very good seafood gumbo, which is a thick kind of soup.”

“Oh, it must be like chowder,” I said. “I think I’ll have a bowl of that, thank you.” And I settled back contentedly, thinking how long it had been since I’d tasted a good bowl of chowder. Mr. Cable and Mr. Clemens looked at each other with amused expressions, probably at my unadventurous choice. But I was more than satisfied, now that I had finally found one of my favorite dishes in a restaurant away from home. Of course, the local recipe would probably not be as good as the real thing from good old New England, but I was willing to take my chances. If the ingredients were as fresh as Mr. Cable said, it could hardly be that great a disappointment. The two older men placed their orders, and talk turned to other matters.

After an interval, the waiter returned with our food, placing a bowl of some outlandish concoction in front of me. “Excuse me, what is this?” I said.

The waiter gave me a puzzled look. “Why, sir, didn’t you say you wanted gumbo?”

“Well, yes, but this is nothing like what I expected. Mr. Cable said it was like chowder.”

“I don’t know nothing ’bout no chowder, but if that ain’t the best gumbo on Chartres Street, I’m quittin’ my job this very day. Go on and try it,” he said, and stood there waiting, with his arms folded across his chest. Mr. Cable and Mr. Clemens, for their parts, sat looking at me with unreadable expressions. Feeling as if I had suddenly been thrust out on a stage without a script, I picked up my spoon and dipped it in the bowl.

I could see good-sized bits of different kinds of seafood, as well as rice and chopped vegetables. And the aroma, while most unchowderlike, was not unpleasant. I took a tentative taste . . . and I think that only the three pairs of watching eyes kept me from spitting it out. Why, the cook must have spilled a whole pot of pepper into it!

Then the rich taste of crabmeat came through the spice. That was certainly good. Perhaps I could pick out the seafood from the rest of the soup, and not sear my palate beyond repair.

I was certainly hungry enough, after the morning’s walking. I dipped my spoon into the bowl again, and the waiter said, “There! Didn’t I tell you that’s some mighty fine gumbo? Plenty tasty, plenty hot. You tell me when you’re done, and I’ll bring you ’nother bowl.” And he turned and went back to the kitchen, satisfied that he had done his duty by me.

“Not much like chowder, is it?” asked Mr. Clemens, a gleam in his eye.

I took another taste and found another flavor of seafood, this one not familiar, although quite good. “That’s crawfish,” said Mr. Cable, watching me eat. I had seen crawfish, looking somewhat like miniature lobsters, in streams back in Connecticut, but never thought of them as food. They seemed right at home in this gumbo, nonetheless. If I could only get used to the excess of pepper, it might be quite palatable. Luckily, I had ordered a glass of the local beer, and it served admirably to wash down the thick soup. And I had worked up quite an appetite. I took another spoonful, and another, and before I knew it, the bowl was empty, and I began to wonder if the waiter really would bring me another serving.

Seeing me devour the gumbo, Mr. Cable waxed eloquent about the cuisine of his native city. (He had ordered another dish with some barbarous name, a mixture of rice, vegetables, chicken, and sausage.) “Why, the worst New Orleans food makes anything you can get in a New York restaurant taste bland, never mind what passes for food in the rest of the North. You’d have a hard time finding a bad meal in this city if you tried for a month,” he said in between forkfuls of his jambalaya.

His smug expression made me want to rise to the defense of my home region, although I knew little enough of the restaurants of New York. But just as I opened my mouth to reply, Mr. Clemens cut me off with a gesture. “Well, George,” he said in the slow, drawling manner that was his characteristic way of speaking, “I’ll have to call you on that. Back in my cub pilot days, I remember a New Orleans meal that nobody at the table could get past their noses. Once we realized it was unfit for human consumption, we tried to get the dog to eat it, and he wouldn’t have any part of it. And when we threw it in the garbage, every single rat in that alley pulled up stakes and headed for Texas. The bugs ate it, though. I know that for a fact, because we found a passel of ’em dead up to a week afterward.” He smiled and nodded, as if in confirmation of his own declaration.

Mr. Cable began to sputter at this slander on New Orleans cooking, but Mr. Clemens continued. “Yes indeed, worst meal I ever had. Cooked it myself. I never made that mistake again.” He took a sip of lager and patted his stomach. “What’s on the schedule this afternoon, George?”

Mr. Cable snorted and shook his head before succumbing to laughter. Finally, he said, “I thought we’d ride out to Lake Pontchartrain and have dinner near West End. It’s only a five-mile ride, but it’ll be much cooler than here in the city, and I know a place where the chef is superb. Half the city migrates out there in the warm season.”

Mr. Clemens nodded. “Fine. How do we get there?”

“The train’s the easiest way, although a carriage ride out the Shell Road is more picturesque. Mr. Cabot might enjoy the view, since he’s new to the city. And you can take the train back, if you’re in a hurry then.”

Mr. Clemens agreed to this proposal, and we settled our bill and walked out to Jackson Square to find a carriage out to Lake Pontchartrain. We soon engaged a smart-looking rig, driven by a wiry little Irishman with bushy chin whiskers and a crooked smile. He took us along the famous Shell Road, a toll road running alongside a canal through swampy land. I saw my first live alligator swimming in this canal; Mr. Clemens, who had told me several stories about these animals during our steamboat trip, kindly offered to have the driver stop so I could inspect the reptile more closely. As the driver seemed to be in a hurry, I was unwilling to interfere with his schedule out of mere curiosity. I prevailed upon Mr. Clemens and Mr. Cable to postpone the opportunity to some indefinite future.

To the landward side, there was a thick forest full of exotic foliage and dark shadows; an occasional path broke the wall of greenery, leading to some destination I could only guess at. Some of the plants could have been giant versions of the house plants I was used to seeing my mother grow, but here they grew—nay, flourished!—out of doors, all on their own. Mr. Cable told me that most of the inhabitants of this territory were poor Negroes who supported themselves by fishing and trapping. The canal itself seemed busy enough; twice we passed tugboats with barges of bricks or other building materials headed for the heart of the city. And the road itself was well-traveled, with a number of gentlemen driving their buggies past us at impressive speed.

Eventually, we broke out onto the lakeshore, a district much like the shore resorts I had seen in Rhode Island: large, lightly constructed hotels with broad verandas and expansive pavilions, close upon the blue waves of the broad lake. Gaily dressed vacationers seemed to be everywhere, enjoying themselves in the warm sunlight. From somewhere in the distance I heard music, a sprightly waltz tune. Small sailboats dotted the water, and a good number of people were taking advantage of the cool waters to escape the late afternoon heat. Mr. Cable told us that another, newer resort had been constructed a few miles away, at Spanish Fort, and that thousands of citizens would come out every evening to enjoy the view, the breeze, the food, the gambling houses, and the band concerts at the two resorts.

We stopped at a little café to wash the dust from our throats, Mr. Clemens and I with an excellent lager, and Mr. Cable (a teetotaler) with a glass of lemonade. Afterward, we strolled along the waterside a while, observing the sights and commenting idly on this or that. An occasional passerby would recognize Mr. Clemens and shout out a greeting, to which he would return some appropriate remark. Finally, at an intersection filled with happy vacationers, a newsboy’s cry seized our attention.

“Read all about it, an arrest in the Robinson murder! Read all about it!”

“An arrest at last!” said Mr. Cable. He reached in his pocket for a nickel. “Here, boy, give me a copy!” The grinning urchin took the coin and gave him the paper and his change, then raised his cry again, hoping to attract more customers.

“It looks as if the New Orleans police know their business,” said Mr. Clemens, as Mr. Cable scanned the front page. “The New York detective who came downriver with us took over a month to spot the man he was after and never did arrest him.”

Mr. Cable’s brow furrowed as his gaze moved down the column, and he finally slapped the paper against his leg. “Read that!” he said, abruptly throwing the paper in Mr. Clemens’s general direction. It hit my surprised employer in the chest and landed on the sidewalk, and I bent to pick it up.

“A travesty if ever I heard of one,” said Mr. Cable. He stamped away several paces, then whirled on his heel to face us again. “An absolute outrage!”

“What on earth is wrong, George?” said Mr. Clemens, looking at the little man with visible alarm.

“Read that story—that pack of lies,” said Mr. Cable, gesturing at the paper I held.

Mr. Clemens took the paper from me, and I crowded in behind him to look over his shoulder. “Here, Wentworth, give me some room,” he said after a moment. “Better yet, you take it and read it to me,” and he handed me back the paper.

I found the story and read aloud: “Police in Orleans Parish today announced they had arrested Leonard Galloway, a Negro cook, on suspicion of poisoning the late John David Robinson. Mr. Robinson, widely recognized as one of the leading lights of Crescent City society, was found dead by his wife, Eugenia Holt Robinson, on Friday the 11th of this month. Dr. Alphonse Soupape, the family physician, recognized the cause of death as poisoning and alerted the authorities. Police had learned that the deceased reprimanded the Negro for drunkenness a few days before his untimely death. Following his arrest at his home on First Street between Howard and Liberty, Galloway was arraigned before J. J. Fogarty, of the First Recorder’s Court, and remanded to Parish Prison to await trial.”

When I had finished, my employer looked at Mr. Cable expectantly. “On the face of it, I don’t see any reason to take issue. What do you know that makes you think otherwise?”

“I’ve known Leonard’s family for twenty-five years,” said Mr. Cable. “His aunt Tillie was my cook when I lived in the Garden District, and Leonard used to come into my own kitchen, watching her work and learning the trade, when he was just a boy. It wasn’t long before he was better than she was. I know that fellow, Clemens. He’s about as likely to commit murder as you are.” Cable’s face was white, and the little man trembled as if he could barely hold back his emotions. One or two of the passersby looked at him strangely, though no one said anything.

“Don’t say that, or they’ll hang him for sure,” said my employer, laughing. I could see that he was trying to cheer up his friend, who had obviously taken the news of the cook’s arrest very much to heart. “Now, if you’d compared him to Wentworth here”—he gestured in my direction—“I’d start raising funds for his defense this instant. But don’t hang a millstone around the poor cook’s neck by comparing him to an old reprobate like me.”

“It’s no joking matter, Sam,” said Mr. Cable earnestly. “The police are obviously at wits’ end, so they’ve arrested a defenseless black man and concocted a reason why he might have had some grudge against poor Robinson, may the Lord rest his soul. If the real killer doesn’t somehow stumble into their hands, they will hang Leonard Galloway, without taking a single further step to find out who really killed Robinson and without even a semblance of a fair trial.” He looked thoroughly dejected as well as angry.

“Well, I wouldn’t want to see the fellow hanged for a murder someone else committed,” said Mr. Clemens, a bit chastened by Mr. Cable’s indignant response. “If it came to that, I suppose I could scrape up some money—I’m not sure where, but I’m willing to try—to hire a good lawyer, if there’s such a critter to be found in this city.”

“There are ways to help a man besides giving him money,” said Mr. Cable thoughtfully. “Perhaps it would be easier for you to donate your time to the cause, instead. You said you thought you could be a detective; here’s your chance. I was joking before, but now I think it would be a good way for you to help poor Leonard.”

“Oh, George, that was just daydreaming,” said Mr. Clemens. “I don’t have any intention of going into the detective business. Besides, I’m way behind schedule on the book I’m supposed to be writing.”

Mr. Cable shook his head. “I know as well as you how much time and effort writing requires, but some things take precedence over ordinary business. This newspaper story will convince the whole city that poor Leonard Galloway is a murderer. Getting him a good lawyer will help, if the case comes to trial, but I’d rather not put my faith in a Louisiana jury. Better to find some way to clear him entirely.”

“That may not be as easy as it sounds,” said Mr. Clemens. “What makes you think he didn’t do it?”

“I’ve eaten Leonard’s cooking more than once. That man isn’t a cook, he’s an artist,” said Mr. Cable. “For him to poison something he’d prepared would be close to sacrilege. But more than that, I know Leonard. He practically grew up in my house. He’s no killer.”

“Maybe so,” said Mr. Clemens. “But that won’t get you very far in a court of law. And people do change, sometimes. Look here, George, you want me to jump into this thing head over heels just because you knew this fellow when he was a boy. But I’ve been bit a few too many times by taking on something when I didn’t know all the facts. If it’s that important to you, why don’t you look into it yourself? You know this city far better than I do: the laws, the customs, the politics, where all the bodies are buried. You’ve done more newspaper work than I ever did. And you know the people. That’s the single most important thing I had to draw on when I solved that riverboat murder. You know the people, and I don’t. Why don’t you do it, George?”

Mr. Cable lifted his head and returned Mr. Clemens’s challenging stare for a moment, then sighed. “I would do it myself, Sam. I’d love to make the pompous hypocrites who run this city quake in their boots. But it won’t wash. I know them, but they know me, as well. Half of them wouldn’t give me the time of day, let alone talk to me about a murder case. If I stuck my nose into what they consider their business, they’d be likely to hang poor Leonard just to teach me a lesson.”

He paced for a moment without saying a word, seemingly oblivious to the carefree vacationers around us. His serious expression was a strange contrast to those of the people walking and laughing as they passed by us. Down by the lake, I could see a group of children skipping stones, and the music of two bands came faintly from the distance. Then Mr. Cable turned and looked my employer in the eye again. “You don’t have enemies down here, Sam. You’re the best-liked writer in America, bar none. Your name will open any door in this city. On top of that, you just solved a murder case that probably had the police chiefs up and down the Mississippi singing your praises. They’d listen to you, even if you were telling them things they didn’t want to hear.”

Mr. Clemens’s face seemed to harden, then a strange glint came into his eye. “Well, I can see you might have a problem or two, George. Oh, hell, give me a chance to think about it a little bit and poke around to see what the facts are. If I’m convinced this fellow really needs help, I’ll do what I can for him. Is that good enough for you?”

“I suppose it’ll have to be,” said Mr. Cable, somewhat reluctantly, to my thinking. “I think you’ll be eager to help once you’ve looked into the case. Can you promise me you won’t shilly-shally around instead of making a decision?”

“First thing in the morning,” said Mr. Clemens. “Meanwhile, there’s important business to be looked into. It’s been twelve years since I had a taste of pompano, and it was as delicious as sin. Find me a restaurant that makes it right, and we’ll show Wentworth just how good New Orleans cooking can be.”

“You’ve come to the right place for that, and I’m just the man to show it to you,” said Mr. Cable. He pointed down the street, and the three of us began walking toward the noise and lights of one of the waterfront resorts. “I’ll tell you what. If we can get Leonard out of jail, I’ll do better than that. I guarantee he’ll cook up the best pompano you ever tasted, and you’ll be my guest to share it with me.”

“You’re trying to bribe me, George,” said Mr. Clemens, grinning. “You know my weaknesses all too well. But are you sure you want to offer me a sample of the man’s cooking before you’ve proven he’s not a poisoner?”

Mr. Cable smiled back at Mr. Clemens. “Once you’ve tasted Leonard’s cooking, poisoning will be the farthest thing from your mind. But come; I know just the place for a pompano, and until we have Leonard to cook for us, it’ll be an acceptable substitute.”

He led us to a garden restaurant from which we could hear the music from a nearby bandstand. As if by tacit agreement to leave the question of the murder case until a better time, the two writers spoke of old times, old friends, and of books still to be written. And the pompano, a tropical fish from the Gulf of Mexico, was every bit as delicious as promised.

* * *

We parted company with Mr. Cable after dinner: he took a carriage back to the Garden District, and we caught a train to the corner of Canal and Bourbon Streets, a short walk from our pension on Royal Street, in the French Quarter. (I had followed the advice of my Baedeker’s Guide and given the local hotels a miss in favor of a suite of furnished rooms.) We settled into a quiet corner of the smoking car and watched the lights of West End fade into the distance as Mr. Clemens puffed contemplatively on one of his corncob pipes.

After a brief silence, I asked, “Why is Mr. Cable so eager to involve you in exonerating this Negro cook? I am surprised at his vehemence on the issue.”

“I’m not,” said my employer. “There’s a lot of courage in that little man, whether you agree with everything he believes or not. And when he makes up his mind about something, he doesn’t give a damn what anybody else thinks. I found that out when we did our lecture tour together as the ’twins of genius.’ If he’d been more willing to bend to the prevailing wind when he lived down here, he might have had an easier time of it.”

“How do you mean?”

Mr. Clemens frowned. “George was a staunch advocate of a fair deal for the colored man long before I first met him. That has never been a popular position to take here in Louisiana, even a dozen years ago, and the tide has been running entirely against colored rights ever since.”

I was surprised. “Is the situation really that bad? The Negroes I’ve seen on the streets seem happy and prosperous enough.”

“You’ve still got a few things to learn, Wentworth,” said Mr. Clemens. “There are laws on the books in Louisiana that deny a colored man the right to sit on a streetcar or in a train, if a white man wants his seat. It doesn’t affect you, so of course you wouldn’t notice it, but the colored man has to live with it every day. He can’t eat in the same restaurant as you can, or shop in the same stores. Hell, it doesn’t matter if his skin’s as light as yours and mine, if the law can prove he had one black great-grandparent. That’s the way the good people of Louisiana want to run their state, and God help any man with the audacity to tell them they’re wrong. George may have been a native, and a Confederate veteran, and the best writer Louisiana has ever produced. That didn’t help his case at all. It just made him more a traitor in their eyes.” His voice took on considerable heat as he spoke, and I looked apprehensively around the car to see if anyone had overheard him, but the nearby seats were vacant, and none of the other passengers seemed to be paying us any mind.

“The ironic part of it is,” Mr. Clemens continued, “George fell out of favor with the Creoles, as well. He tried to portray them honestly and accurately in his writing, which is exactly what a writer is supposed to do.”

“Who exactly are the Creoles?” I asked. “I thought they were the descendants of the original French settlers.”

“They all speak the patois, but there’s Spanish blood in the mix, as well as French, and sometimes a touch of the African or Indian, too. George probably has as much real affection for them and their way of life as any man alive. But when he published his books about the old times in New Orleans, some of the leading Creoles thought he was mocking them—the stiff-necked fools! And so, between them and the damned lily-white bigots, George found himself surrounded by enemies in his own hometown. Finally, a few years ago, his friends convinced him to move to Massachusetts, where his opinions were less likely to bring armed men to his door.”

“Ah, I thought he still made his home in Louisiana. Why on Earth has he come back, then, if he has so many enemies here?”

“The same thing that brings me back: writing a book. A man can only trust his memory so far, Wentworth. There comes a time when you have to set foot on the ground you’re writing about, even if it costs you a certain amount of pain. Despite all that’s happened to him, George still loves this place. I can understand why. If you’d spent the first part of your life eating meals like that one tonight, could you live out your days in New England, knowing you were condemning yourself never to taste pompano again? For a plate of fish cooked like that, and an evening of talk like that, I’d make a dinner date with the devil himself, even if the table was set by the hottest furnace in Hell.”

I wasn’t certain I’d go to quite that length, but I had to admit that, barring the local predilection for excessive spice, I could easily grow accustomed to the food in New Orleans. And, after Mr. Cable’s extravagant praise of Leonard Galloway’s prowess in the kitchen, I found myself almost wishing that Mr. Clemens would decide to help the poor fellow, if only so I could sample his cooking.