Читать книгу Making Kantha, Making Home - Pika Ghosh - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

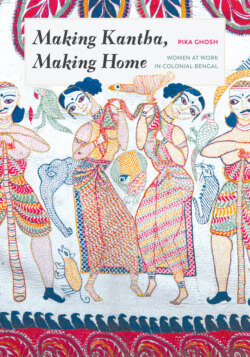

Introduction Kantha, Comfort, and Canon

ОглавлениеIREAD THE VELVETEEN RABBIT AND STORIES LIKE IT OVER THE YEARS AS I snuggled under the covers with my children at bedtime.1

The Skin Horse had lived longer in the nursery than any of the others. He was so old that his brown coat was bald in patches and showed the seams underneath, and most of the hairs in his tail had been pulled out to string bead necklaces. He was wise, for he had seen a long succession of mechanical toys arrive to boast and swagger, and by-and-by break their mainsprings and pass away, and he knew that they were only toys, and would never turn into anything else. For nursery magic is very strange and wonderful, and only those playthings that are old and wise and experienced like the Skin Horse understand all about it.

“What is REAL?” asked the Rabbit one day, when they were lying side by side near the nursery fender, before Nana came to tidy the room. “Does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?”

“Real isn’t how you are made,” said the Skin Horse. “It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real.”

“Does it hurt?” asked the Rabbit.

“Sometimes,” said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. “When you are Real you don’t mind being hurt.”

“Does it happen all at once, like being wound up,” he asked, “or bit by bit?”

“It doesn’t happen all at once,” said the Skin Horse. “You become. It takes a long time.

This wasn’t a story from my own childhood, but it could easily have been, as I grew up in an era quite different from the glittering worlds of post-liberalization India. It was a time when signs of generations of wear and respectability were apparent on the shabby, genteel facades of houses and on white school uniforms that remained obstinately off-white, when potato peels were carefully saved to be cooked into a delicacy with a sprinkling of poppy seeds, and old, yellow-gray cloth was mended and stitched into something new by grandmothers and mothers. In hindsight, I realize that part of me became real through these ordinary, everyday intimacies.

All of that is changing now in Kolkata/Calcutta, and I too have moved on, but kantha that are created from old cloth carry that peculiar thickness of touch and wear, emotions, experiences, and memories—like worn stuffed toys—among the people I have encountered and worked with over the past decade of living with this book.2 Kantha blankets and mats become real as children wiggle in their warmth, extending their presence with sighs and sniffles, the drool of deep sleep, or the consternation of “accidents” (fig. I.1). Kantha embody their human companions, participating in the rituals that construct ordinary lives (figs. I.2, I.3, I.4). They constitute the most intimate everyday realities not only of their users, but also of those who take care of kantha, those who take pride in their family’s distinctive practices, and those who pause to revel occasionally in their remembrances. Kantha, in anecdotes, can meander from the quotidian to the heirloom, with various valences in between. And all kantha, of course, are malleable, potentially moving with ease and subtlety, often unremarked, across these registers of everyday life and perception. They share in the slipperiness, even capriciousness, of ordinary things that are so often taken for granted, much like stuffed bunnies.

Such ephemeral qualities inevitably make these objects obdurate as well. They cohabit multiple temporalities, from the cloth that soaks up tears to the memories that cause more to well up. They can be multigenerational, used for one baby and then put away, sometimes until the next generation arrives (figs. I.2, I.3, 1.11). They refuse to be confined to bedroom interiors or home altars. They can move inside and out with the weather (figs. I.4, I.5, I.6). Some undertake ceremonial journeys from one home to another (fig. 1.11). And sometimes they travel unceremoniously in hand luggage. Some move beyond these confines in memories, feelings, conversations, and writings. They seem to elude my efforts to home in on any stable definition for all the different kinds of things I have encountered. For the most part, though, kantha continue to be understood in common parlance as textiles created from layers of used, worn, even frayed fabric, usually extracted from garments such as women’s saris and men’s dhotis. They have been closely associated with the work of women and domestic environments. The repurposed-cloth shawls or wraps, blankets, bedspreads, seating mats, infant receiving sheets, and diapers are integrated into the everyday lives of Bengali families, into household rituals and more formal ceremonies (figs. I.2, I.3, I.4, 1.6).

I.1. Srinjan Das as a two-day old infant, lying on a rectangular baby kantha for everyday use. The baby’s bottom is wrapped in old cloth from a worn sari, believed to be soft enough for his new skin. Kolkata, June 2008.

I.2. Tito Basu sits on a floral kantha during the celebration of annaprashan (ceremony marking an infant’s first taste of solid food). The red and gold patterned border of an old sari was attached to give a ruffled edge to this kantha after the base layers of cloth were secured to create the rectangular field. Chapel Hill, NC, June 2013.

I.3. Kantha are multigenerational. This infant kantha features an embroidered poem. Both this kantha and the poem were created by my paternal grandmother, Preeti Ghosh, at the time of my birth. In the poem, she weaves the three generations together through wordplay on names. Here, it is reused during a ceremonial blessing of my son. Chapel Hill, NC, June 2013.

I.4. Chandra Basu spreads one of a set of small, square kantha seating mats (asana, ashon) for a ceremonial meal in the courtyard of her family estate on the occasion of Durga Puja. Memari, Bardhaman district, West Bengal, October 2007.

I.5. Kantha cut across class. Below, a homeless woman dries her tattered kantha on a roadside wall. Above, wealthier homeowners dry theirs on rooftop clotheslines. Bishnupur, West Bengal, fall 2007.

I.6. Square seating mats made by Malati Das are spread on the rooftop to dry and disinfect in the sun. Bishnupur, West Bengal, 2007.

I.7. Short, dense, white running stitches secure the base white cloth of this kantha, while looser running stitches in colored threads of embroidery secure the woven border. Detail. Attributed to early twentieth century. Bengal. Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection, 2009-250-3.

Such traditional kantha are associated with a distinctive process of making. It starts with retrieving soft, white, much-washed cotton cloth from discarded articles.3 This base fabric is prepared by darning, patching, layering, smoothing free of wrinkles, and securing at the corners and across the field with long, loose, running stitches in white thread.4 The same basic running stitch may be manipulated intricately, along with a few other stitch types, by extraordinarily skillful hands to create exquisite patterns and pictures in colored thread. Something ordinary that has lost its utility is thus transformed into a new, useful, often precious and beautiful thing.5

Variations on the running stitch range from long, loose stitches spaced wide apart to create a fluffy softness comfortable for babies’ bottoms, to more uniform, short, evenly spaced, parallel rows, creating a dense and durable surface for blankets, bedspreads, and seating mats (ashon, asana). Rows of running stitches may be worked into shapes and patterns and a rippling or swirling texture that is mesmerizing to behold (figs. I.7, 1.7, 1.14, 3.19).6 However, kantha have also been made without the use of the white running stitch to fill the background, most often when the foundation layers of cloth are not heavily worn and so do not require stabilizing, or when the embroidery is so dense that it serves the purpose (figs. I.9, I.11, I.12, I.15). Moreover, the white running stitch can also be used primarily for design rather than restoration or repair (fig. I.8).7

I.8. The short, dense, white running stitches are used discerningly, integrated into the ornament of this kantha rather than used exclusively to fill the background. Detail. Attributed to second half of the nineteenth century. Bengal. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Stella Kramrisch Collection, 1994-148-686.

As in most everyday art forms, there are myriad variations of the practice, contingent, for the most part, on the particular materials selected, the purpose intended, and the skill and creativity of the maker. Colored threads for the embroidery may be extricated from the ornamental woven border patterns of the original or other reused fabric by deft and thrifty makers for surface embroidery. The self-referentiality can be intensified when embroidery on kantha borders replicate the woven patterns on sari borders (paar) (fig. I.9). And a long tradition of adorning kantha exclusively by filling the surface densely with stitched rows of woven border patterns continues into the present (fig. 1.4), examples of which may be displayed by skilled embroiderers to demonstrate their knowledge and expertise in local conventions.8

These recycled textiles have been imbued with extraordinary potency, entangled with the intimacy of touch and its transfer from one set of hands to another.9 Through such contact and transmission, they can embody relationships spanning great distances and over several generations. Stains, patterns of wear, and darning layer their physical traces and sometimes intensify emotional bonds (figs. 1.13, 1.14, 2.1, 3.7). Kantha are endowed with the ability to help make houses into homes, usher new life into the world, give comfort in faraway places, connect individuals to families, and renew relationships. They ease and embrace seasonal change, from soft balmy summer nights to the crisp chilly air of late autumn (hemanta) evenings when blankets bring coziness, warmth, comfort, and security (aram) (fig. 1.16). Such associations, which span class, gender, urban and rural communities, Hindu and Muslim, West Bengali and Bangladeshi, powerfully connect kantha to what it means to be Bengali. One of the aims of this book is to gain insight into the social, political, historical, and familial processes whereby kantha accrued such force in fashioning lives, relationships, and social worlds from nineteenth-century written accounts to popular perception today. It attempts to shed light on the processes and the shifting contours of what constitutes a kantha, focusing on the earliest objects surviving from the middle decades of the nineteenth century.

I.9. With its horizontal repeated motifs and thread colors, this embroidered kantha border simulates a woven sari border. Detail of kantha. Attributed to second half of the nineteenth century. Bengal. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Stella Kramrisch, 1968-184-13.

Herein also lies a potent resource for seeking out the women who were making these kantha. Their handiwork indicates that they were putting down their ideas with needle and thread, sometimes signing their names in stitches at about the time when the first few Bengali women were beginning to write and publish their memoirs and autobiographies. They are the forerunners, in some ways, of the women who became visible at the forefront of the nationalist movement in the last decades of the century. Kantha, often embroidered with vivid and provocative images and supplemented by a range of inscriptions, offer us avenues to probe how women understood their work and how they found ways to express their creativity, sometimes despite the scrutiny from Bengali men and European reformers. Their kantha invite us to ponder how these women may have contemplated their worlds and the wars waged at the time, how momentous events outside impacted their households, how they held their ground, asserted themselves, explored the possibilities of restrained yet resolute dissent or discontent and even toyed with alternative visions. The enormous potential for textile as archive for complicating some of the images that were constructed for Bengali women as hapless, mired in meaningless ritual, seems to have gone neglected. If colonial discourse endorsed such passive images to justify subjugation as moral reform, the modernist project of enlightened Bengali elite men celebrated women within households, primarily as repositories of tradition and authenticity.10

More recently, historians have drawn attention to a handful of the women from the middle decades of the nineteenth century. They have been celebrated for their activism, for the most part encouraged by male mentors within family circles. More exceptional is the stage actress Binodini Dasi, who rose to prominence from the ranks of prostitutes, albeit with a prominent male patron.11 Yet the opportunities for everyday critiques and hints of alternate visions also lurk in expressions that were familiar, safe, and integrated into everyday life and ritual.12 Analysis of kantha embroidery suggests that we might usefully begin to recognize the women who wrote their accounts as a much smaller subset among those who pondered the issues across a range of media.

To listen for their voices also requires situating their works in the couple of hundred years of kantha making that is documented by surviving material. The diversity of creative and pragmatic innovations in the move toward commoditization and institutionalized production of kantha teaches us to look for similar responsiveness in older textiles from the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Such changes, visible in the objects, and my own observation of processes of making and use today, alerted me to heed shifts in nomenclature in my conversations with practitioners over the course of a decade of fieldwork trips. Fundamental among these are qualifications such as “ashol kantha” (real kantha) or “nakshi kantha” (elaborately designed ones, embellished with embroidery) that explicitly differentiate the older continuous practices from more recent interventions, including the factory-like production environments across Bangladesh and West Bengal that have been spearheaded by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and sold at exclusive boutiques and international outlets.13 In other conversations, I noticed that by designating the latter “modern kantha,” the unqualified term “kantha” was implicitly conferred on the older, traditional practices.14 Such adaptations in vocabulary acknowledge the elasticity in practice and have undoubtedly played a key role in the endurance of kantha, witnessed in multiple “revivals” over the twentieth century. Through these terminological distinctions runs a preoccupation with distinguishing the range of continuous innovation in domestic practice, accommodated within the ideals of “kantha” as it is embodied at particular historical moments, from the commercialized spheres of production—while at the same time recognizing that the two are mutually constitutive and continually interactive.15 Although differentiating old from new kantha betrays values and anxieties about tradition versus modernity, the categories do not always correspond in straightforward ways.

I.10. Anima and Banasree Nag Chaudhuri display a quilt made by Banasree constructed of small square patches of cloth left over from other projects. Kolkata, October 2007.

Despite the tendency to speak of domestic kantha making as unchanging, the works from the past fifty years reveal as much experimentation as commercial production. Innovations have incorporated new stitches, techniques, tools, and materials, from jute sacks, plastic sheets, and wool, to raffia and beads.16 Iconographic experiments draw from long-standing favorites as well as whimsies. Humpty Dumpty, Donald Duck, Goldilocks, Shrek, and Tuntuni (the tailorbird who outwitted the king) have all debuted on baby kantha (figs. 1.13, 1.14).17 Likewise, ruffles, pleats, fringes, and tassels (figs. I.2, I.6), the replication of particular sari border patterns and motifs to different effects (fig. I.9), and embroidered paisleys in imitation of the jamavar shawls from Kashmir (fig. I.14) indicate fondness for the familiar and flirtations with the trendy. They point to the flexibility and mutability that always inhered in everyday practices; their choices indicate that women recognized these surfaces as a suitable venue for their vision and aspirations.

Kantha from the later decades of the nineteenth century equally display figures and events that caught the attention of their makers. They range from sensational events discussed and visualized across many media, such as the Tarakeshwar temple scandal that rocked the region in 1873 (fig. I.11) and the rising excitement at the first hot-air balloons displayed in circus acts some years later (fig. I.19).18 Bindhabashini, for example, stitched the Tarakeshwar affair in a sequence of three pairs of figures on a kantha two years after the event. Her embroidery may shed light on processes of making sense of near-contemporary events, and perhaps, too, on her observations about newspaper accounts, journal articles, street songs, theater, cheap printed images, and watercolors. Further, in partaking of the visual vocabulary in vogue at a particular moment across various visual, textual, and performative genres, her embroidery yields clues to the compositional arrangements and juxtaposition of motifs on nineteenth-century kantha as to what could have been deemed appropriate to visualize in embroidery at the time. A sensational murder case at the Hoogly Sessions Court in Serampore (Srirampur) brought to the forefront of public awareness the complications navigated by young women, specifically the abuse of power by religious leaders, the discourses surrounding rape, chastity, and femininity, and the anxieties about official intervention.

In this case, Madhavchandra Giri, the mahanta (guru and manager) of the popular Shiva Temple and pilgrimage center at Tarakeshwar, was accused of seducing and raping Elokeshi while her husband, Nabinchandra Banerji, was away working in the city, an act that culminated in her brutal murder with a boti (a curve-bladed kitchen knife) by Nabin.19 Bindhabashini has juxtaposed two dramatic scenes from the narrative, which was visualized both in single scenes and as larger sets in other media such as Kalighat watercolors and Battala prints (fig. I.12). As in some of these versions, Bindhabashini identifies the figures with brief captions. However, her adaptations from such popular compositions in describing the interactions among the three characters suggests her interests. For the interactions between the mahanta and Elokeshi, she elected to depict his aggressive advance—his grabbing her by the hand—rather than a scene of seduction and enticement such as offering her condiments or intoxicants in the form of paan (betel) or hookah as visualized in other media. Bindhabashini complements this assault with a second violence. Nabin approaches her with fish knife in hand, as Elokeshi crouches, begging forgiveness and mercy.20 Contemporary viewers likely knew the outcome.

Not embroidered here are some of the intermediary scenes in painted and printed sets that include Nabin forgiving his wife when she first confessed and the resolution of the case with the imprisonment of the mahanta. Distinct from the brutality of these two stitched scenes, a third one features Shiva and Parvati, the gods who are worshipped at the Tarakeshwar temple. Here, the divine couple are presented somewhat unusually with hands clasped, the intimacy pronounced by their raised arms. Bindha-bashini’s version of these deities thus marks a departure from the lingam, the black stone pillar-like form of Shiva preferred for worship in Bengali temples.21 It also strays from the typical watercolor and print iterations that present the Tarakeshwar lingam with three bel leaves upon it, signifying ritual worship, with the mahanta and Elokeshi on either side of the icon (fig. I.12).22 Instead, she interprets the deities as images of conjugal harmony. This divergence signals a choice, particularly because Bindhabashini demonstrates familiarity with the visual vocabulary of the Tarakeshwar scandal that was emerging in other media in the two previous vignettes. She thus invites us to pause and linger on the drama she contemplates, to look for her position on this disturbing event that women were surely mulling over and on contemporary discussions of appropriate behavior, conjugality, and chastity.

I.11. Vignettes from the Tarakeshwar scandal: the rape of Elokeshi (left); Nabin killing Elokeshi (center); and a temple with Shiva and Parvati holding hands (right). Detail of kantha. The inscription around the central lotus identifies the maker as Bindhabashini, who dedicates her work to the goddess Durga. It also offers a location and date: Sangpecharoi, completed in 1875. K. C. Aryan Home of Folk Art, Gurgaon. Photograph courtesy of Shubhodeep Chanda.

Kantha imagery from the late nineteenth century also engaged in the visualization of the emergent nation as goddess, a central preoccupation of these decades in Bengal. On some textiles, she is identified with Durga, through stitched and printed captions; in others, her identity is assumed. She appears in Durga’s martial posture, frontally oriented astride her lion, her hands directing weapons toward the enemy to her left (fig. I.13). She fights men on horseback, who are often depicted wearing hats and shoes and brandishing muskets or swords in the imagery of the colonial period. On Bindhabashini’s kantha, these riders are identified as Shumbha and Nishumbha, a set of demons that Durga destroys in the popular tale of her emergence to power.23 However, their attire and appearance, together with the addition of a third figure, marks a shift from the typical battleground with strewn corpses. The composition of three overlapping riders here instead resembles the Kalighat watercolor of three jockeys at the horse races. Their similar attire is distinguished by alternating colors. Sleek horses gallop at full stretch with outstretched necks and wind in their tails.24 Instead of a finish line marked by a flag, her embroidered riders confront the goddess. Such innovations give contemporary face to these Puranic demons, perhaps as Europeans engaging in their favorite pastimes in the city. Bindhabashini’s interpretation is contemporaneous with Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s iconic novel Anandamath, with its rallying cry for a more active nationalism, Bande Mataram, hailing the goddess as mother of the nation.25 Bindhabashini dedicated her work to the goddess in the kantha’s central circular inscription, a move that also resonates with similar gestures in the literary genres. Such embroidered images alert us to the active engagement of women in imagining and giving this new form to the deity, and with it, the nation. These stitched figures are material evidence of their participation in the political debates of the day, alongside the better-known ones taking place mostly among upper- and middle-class Bengali men in the outer formal reception areas (baithak khana, bahir mahal) of elite residences.26

I.12 A pair of scenes from the Tarakeshwar scandal: Elokeshi is presented to the mahanta (head priest) Madhav Giri (left); Nabin attacking Elokeshi with a kitchen knife. Probably last quarter of nineteenth century. Battala woodcut print. Kolkata. 46.8 × 27.8 cm. Private collection. Photograph courtesy of Ashit Paul.

I.13. Durga astride her lion, destroying the demons Shumbha and Nishumbha (variant spellings of their names are embroidered below the lion), is recast here as a confrontation with three riders in European outfits. This innovative interpretation of the goddess’s feat suggests the conflation of Durga as slayer of demons with Bharat Mata, the goddess embodying the emergent nation, who appears as a major literary figure at just this time. Detail of kantha. 1875. Sangpecharoi. K. C. Aryan Home of Folk Art, Gurgaon.

This imagery also reiterates that we recognize the permeability of the homes where women embroidered. If we know that where there were walls, there were also screens and swing doors punctuating them, giving access to those who were walled off, embroidered images suggest that women availed themselves of such porousness. Just as they viewed dances and other entertainment in the outer reception halls through screens and slats and observed the happenings in the streets outside, not surprisingly, women’s visualized thought indicates that they grappled with the political debates raging through the region. These complications belie binary constructions of the andarmahal (inner recesses, living quarters) at a remove from areas of public reception, which were used to map interior spheres of female purity and male outward and worldly orientation toward jobs (chakri), the commercial engagements of Bengalis in the making of British colonialism.

Such visible traces from the past suggest that women claimed kantha as a safe site for their thoughts and outlet for their creative energy. Women who may not have had the luxury to choose other media for self-expression due to lack of economic resources, social access, or particular kinds of literacy and training found their space here. They have left us their perceptions of their worlds in layers of used cotton cloth, secured with running stitches and adorned with images created in colored threads. Their needlework is often the only trace of their presence to have survived. Therefore, the significance of these textiles as glimpses into the creativity and agency of women through their handiwork, alongside their written accounts, cannot be overstated.

This book endeavors to listen for these voices from the textiles by considering what women have chosen to depict and how they have done so, while remaining mindful of what they may have ignored or dismissed. From these visual archives, which have not previously been examined for such purposes, I reflect on the distinction between the valorization of kantha in the nationalist idealizations of home and the world, insides and outsides, and the visualizations by nineteenth-century embroiderers that inhere in the objects themselves. The book thus reevaluates the fundamental question “What is a kantha?” through a patchwork of perspectives and approaches. In so doing, it draws attention to the vast spatial reach of textile practices alongside the intensely individual and local preoccupations visualized in the imagery, the play of touch and emotion, and the generation of memory intrinsic to such fabrics. If they were imaginatively deployed in the mobilization of anticolonial nationalisms, such potent, portable objects continue to engage diasporic reorientations of territorially based nationalisms and patriotisms. In their extraordinary malleability, kantha carry the comfort of home and family in their sojourns with those who have settled into communities that have coalesced in Singapore, Malaysia, Sydney, London, Paris, New York, and San Francisco.