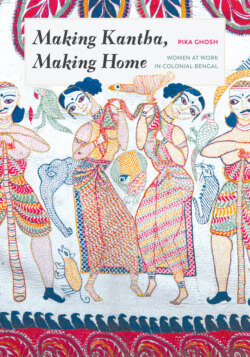

Читать книгу Making Kantha, Making Home - Pika Ghosh - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FABRICATING DOMESTICITY

ОглавлениеEven though kantha never quite made its presence felt in the textbooks that we use for teaching South Asian art today, it entered the deliberations among Calcutta’s intellectual elite about constructing the parameters for a narrative about Indian art relatively early. Sited for the most part in and around the capital of the vast British Empire in India, this dialog was inevitably tied to the shifting strands of nationalist thought and agendas from the late nineteenth to the first few decades of the twentieth century. The voices spearheading this endeavor were equally numerous, and included sympathetic Europeans, who brought their diverse intellectual backgrounds and ideological perspectives to the understanding of kantha and its deployment in the service of nationalist ideals. At the forefront was the notable Tagore family. The group also included Gurusaday Dutt, the colonial civil service officer and folklorist; Stella Kramrisch, the Czech-born Jewish art historian from the Vienna School, who came to Shantiniketan in 1922 at Rabindranath’s invitation to take up a teaching post at the newly established experimental Visva-Bharati University; Ernest Binfield Havell, founder of the Indian Society of Oriental Art and principal of the Government Art School from 1896 to 1905;42 Ananda Coomaraswamy, the geologist and art historian of English and Sri Lankan parentage; Okakura Kakuzo, the visiting Japanese scholar seeking to further a pan-Asian unity; the literary giants and educators Asutosh Mukherjee and Dinesh Chandra Sen; and folklorists, poets, novelists, storytellers, and artists such as Dakshinaranjan Mitra Majumdar, Jasimuddin, Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, and Jamini Roy. They followed the lead of an earlier generation of English-educated Bengali intellectuals such as Raja Rajendralala Mitra, who had challenged colonial assessments of Indian art as derivative and debauched in the era of suspicion and mistrust following the confrontations of 1857.43 Impelled by anticolonial agendas, these public intellectuals tested out a range of strategies to refute such allegations, which were critical to fueling nationalist thought further.44 Rehabilitating Sanskritic terms such as shilpa, they sought equivalence for Indian art vis-à-vis European art, while at the same time expanding the contours of “art” in its dominant European definition inherited from Hegel and Kant. Some turned to the range of everyday domestic practices, beyond the corruptions of the outside world of work and colonialism that had failed to fit in the purview of “art.” Their embrace of such artistic practices, including kantha, were inevitably deeply entangled with the Arts and Crafts project that had identified a goldmine in Indian designs and wares to alleviate the alienation and aridity of industrial modernity and its commercial products. Such endeavors thus contributed to reinscribing the anonymity and handicraft status of works of embroidery that bear the stitched names of their makers.

Many turned to rural Bengal in a search for origins, a quest unmistakably laced with longing and nostalgia for a pure Bengal, a golden Bengal (shonar Bangla), which they located beyond the contaminations of the colonial capital. Dinesh Chandra Sen, for example, located Bengal itself in richly multisensorial remembrances of things and their material qualities. Their participation in rural household rituals triggered deeply emotional responses that color his prose:

The sound of conch shells and bells every morning and evening, the sweet smell produced by burning of incense and sandalwood, the ever-emergent red color of lotus flowers—it was as if they all filled up Bengal villages, their marketplaces, fields, ghats, and pathways, with an atmosphere of devotion to God. I began to consider the dust of every village of my motherland sacred. This was nothing like the [new-fangled] emotion of nationalism or patriotism on my part. Nor was it a feeling produced by simply copying the English. Truly did every particle of dust of this land make my tears flow. An indescribable feeling of attraction made me fall in love with the land of Bengal.45

Not surprisingly, most of the Bengali men engaging in such conversations in Calcutta could relate to such effusive responses through shared familiarity with such experiences, as they traced their origins back to the countryside, to homes in Sylhet (Gurusaday Dutt), Bankura (Jamini Roy), Bardhaman (Nazrul Islam), Faridpur (Jasi-muddin), and Dhaka (Dinesh Chandra Sen). Others, such as the Tagores, maintained estates in rural areas (Kushtia), where they sought frequent refuge from the city.46 Positioning kantha in the dialogs committed to recovering and valorizing an authentic artistic tradition must be understood in this romantic conceptualization of rural Bengal, defined by its ritual practices, abundant natural resources, and agricultural plenty.47 Such ideological moves tend to abnegate the ordinary, everyday practices surrounding kantha, its making, distribution, and use, which accompanied the women of various classes who also settled in the capital city. Moreover, many of these women also traveled back and forth between rural and urban residences, despite the travails involved, as did kantha and kantha-making conventions and innovations.48

The civil service officer Gurusaday Dutt, who acquired the exquisite kantha gracing Mitter’s volume (fig. I.14), accumulated what is today recognized as the most important historical collection to have survived.49 During his administrative assignments in rural and remote areas of Bengal, Dutt indulged his love for local art forms and his passion for kantha, painted scrolls, wood carvings, and metal wares, among other material artifacts. However, he does not seem to have left detailed records about the particular circumstances of their acquisition beyond the names of their makers and sites of collection.50 Despite the inscription on the kantha bearing its maker’s name, Manadasundari Dasi, the sheer paucity of written information about Manadasundari of Mulghar surely aided in relegating her creation with other non-canonical ones. Ardent nationalists such as Dutt hailed kantha as an essentially unchanging, traditional, “living form” and a “spontaneous expression and inseparable part of the life of the people.”51 Yet they erased the specificity of the living experiences of makers and users, from whom they extricated and institutionalized the textiles.52 That obliteration, in turn, contributes significantly to consigning to kantha the status of handicraft rather than art. The discussion by Dutt and his compatriots is, instead, uncompromisingly swadeshi (of the homeland, homegrown), enmeshed in the sociopolitical upheavals leading up to and following from the British administration’s decision to partition the region.53

Such location of kantha in the recovery and preservation of cultural practices for the reconstruction of origins in the service of regional cohesiveness and patriotic sentiment coincided with the resurgence of folkloristic interest in “peasant art” in Europe. The multiple cosmopolitanisms embraced by Calcutta’s thriving intellectual community suggests that some participants were attentive to such movements as they looked to mainland Europe for models to counter British colonialism.54 They traveled through Europe and across Asia, engaging with contemporary ideologues, artists, and poets beyond Britain, from Germany, Austria, France, and Spain.55 As historian Sugata Bose has succinctly observed, “Anticolonialism as an ideology was both tethered by the idea of homeland while strengthened by extraterritorial affiliations.”56 The Tagores were equally invested in Okakura’s vision of a pan-Asian unity in their pursuit of alternate models of universalism. At the same time, they maintained close ties with Gandhi’s rally for swaraj (self-rule).

The recuperation of kantha, along with kirtan (devotional songs), alpana, and brata (vows), toward consolidating Bengali identity in the face of the region’s proposed partitioning, was inflected by such diverse agendas. Kantha became firmly ensconced in a romanticized, pure, rural imaginary, the foil to colonial modernity in the prodigious literary output of the first quarter of the twentieth century.57 And they became inseparable from Indian nationalism, from swadeshi as it was imagined in Calcutta. As with other local practices in imperial or colonial contact zones, the attention bequeathed to kantha highlights the politics of domination and subjugation.

At the same time, kantha became imbued with magical qualities. Long-standing associations of kantha with rags and poverty—and intertwined with it, the bodies of mystics (Bauls, fakirs, and bairagis) and their rejection of worldly ways—lent easily to such interpretation.58 Chaitanya, the Bengali saint who had come to be understood as the personified divine, is repeatedly imagined draped in a kantha, perhaps protecting his vulnerable body, which was famously prone to ecstatic fits.59 A well-known song of Lalan Fakir, the best known of the Baul (a marginal mystic-minstrel community), captures the elusiveness of the spiritual quest as one that is experienced bodily and transmitted through bodily contact through kantha: “Listening to Lalan Shah’s emotional state gives one a headache / But wrapping oneself in Lalan’s torn kantha keeps the cold away.”60 Rabindranath Tagore in particular was drawn to such poetic imagery in the search for local cultural practices to stage anticolonial resistance.61 The interest in practices such as kantha, shared by Hindu and Muslim Bengalis, coincides with investment in indigenous mystical expressions drawing conspicuously on shared imagery or denouncing the limitations of both.62 As the fissures between Hindus and Muslims threatened to take on ominous proportions, a shared textile practice in the domestic sphere offered a tangible body of material and symbolic power to espouse commonalities and mobilize public sentiment toward a “Bengali” identity. Kantha can thus be located in the intensified search to transcend communal investments and to test the limits of empire around the time of the first partitioning of the region that was proposed in 1903 and implemented in 1905.

But shrouding kantha in mysticism and bestowing a sacred genealogy also obscured locally understood distinctions between several related textile conventions across a region that was larger than France.63 Stella Kramrisch, for example, constructed a chronological narrative in 1939 about valuing rags to further her argument about restitution, wholeness, and cosmic integration:

In the Kanthā, the symbolic action is equally in the embroidery and its material. It is embodied in its texture by restoring wholeness to rags, by joining the torn bits and tatters and by reinforcing them with a design of such a kind that when a Kanthā is spread out, it unfolds the meaning on which life is embroidered.64

Through a strategic sequence of analogies from Rig Vedic visions of the universe as a fabric woven by the gods and the Buddha’s tattered robes, she sought to bequeath these domestic fabrics legitimacy in cosmopolitan artworlds, and by association, with a more widespread spirituality beyond the mundane spaces that the textiles typically inhabited.

The conflation of kantha with value and virtue percolated deeply through corpuses of children’s stories, gathered in printed form as the preoccupation with textbooks and education emerged to the forefront of nationalist thought. One of the best known, Abanindranath Tagore’s Kshirer Putul (1895), the miraculous tale of a boy modeled from condensed milk and animated by the goddess Shashthi, participates in such idealization of kantha.65 At the same time, the story underscores the potency of kantha as inseparable from women’s lives, their bodily and emotional solace, and from central concerns defining their social status such as fertility. In the tale, Duorani, the king’s first wife, whom he had abandoned for a younger, gorgeous, second wife, is banished from the palace. Implicit in such a scenario is the misfortunes of women who could not successfully bear children to secure the patrilineage. The older queen has little leverage in the social networks of the court as she did not have a son to confer stature upon her, and she is repeatedly portrayed lying on the floor of her hovel with a kantha for comfort, in marked contrast to the younger queen, who is draped in exotic gems, golden fabrics, and other luxuries. Meanwhile, the kantha, holding the tears of the abandoned first wife, witnesses her trials and tribulations. As the story unfolds, the besotted king realizes that he is unable to fulfill his younger wife’s insatiable greed and sees the error in his judgment and treatment of the loyal, elder queen. Duorani is finally rewarded in a tale that entwines kantha with poverty, hardship, and female virtues such as unswerving loyalty, resilience, compassion, and nurturance.66

The return to rags and the rhetoric of poverty as ethical and spiritual wealth was a strategic espousal on the part of an educated elite. The comparison between the good and evil queens surely alluded to the political disaffections on the ground and perceptions of a rapacious and capricious ruling elite, an impoverished and ostensibly helpless Bengali population, and the promise of restitution. Further, issues of infertility and inheritance were at the core of the first widespread challenge posed to British authority in 1857; the British refusal to acknowledge the rights of adopted heirs had incited several north Indian local kingdoms to mobilize their troops.

At the same time, however, these influential narrators acquired kantha collections that belie the romantic image of noble, or humble, rags. What survives from the collections of the Tagores, Gurusaday Dutt, Stella Kramrisch, Dinesh Chandra Sen, and Asutosh Mukherjee are exquisite embroideries, displaying concerted labor, skill, planning, and imagination. Today they form a significant majority of museum holdings across the world. Looking back, it is easy enough to recognize a notion of “taste” shared among this cosmopolitan urban elite.67 It was reaffirmed and replicated as these collections inspired the more institutionalized production of kantha that emerged hand in hand at centers such as Kala Bhavan, the school of arts of Tagore’s Visva-Bharati University at Shantiniketan, and the women’s samitis (associations) established by social reformer and educationist Saroj Nalini Dutt.

I.15. Kamala’s kantha. Attributed to nineteenth century. Collected by Stella Kramrisch. 95.2 × 95.3 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Stella Kramrisch, 1994-148-705.

Their narratives, moreover, elide the complex processes of acquiring textiles that once belonged in homes and families, often with the names of makers, recipients, and personal messages in visual and textual stitched form. As they laid the groundwork, creating awareness through collecting kantha, housing the material in newly established museums and curating exhibitions, ironically, the voice and valorization of kantha as a women’s spiritual practice was predominantly from an elite male intellectual cohort. As art historian Debashish Banerji has reminded us, Abanindranath Tagore acquired material for such work from the women of his intimate family circle in the Jorasanko household and through observation of the practices of its women.68 Likewise, the pioneering efforts of Saroj Nalini Dutt toward institutionalizing vocational training for women, including sewing, weaving, and embroidery, is hardly a footnote in studies of Bengali history;69 the enthusiasm of her husband, Gurusaday Dutt, on the other hand, is noted assiduously in analyses of women’s upliftment efforts. If the scholarship on the manifold collaborations between colonial anthropologist and native informant has been the subject of intense scholarly scrutiny, such intimate alliances equally complicate the prevailing picture of male scholars speaking on behalf of vast numbers of women, who remain unacknowledged, and often unnamed. Furthermore, if predominantly male-authored ideologies were projected on the body and sphere of influence of Bengali women, not all Bengali women were so privileged. Rather, it was unambiguously the woman who was married, bore children, and took care of the family and household.70 Younger girls, prostitutes, unmarried or widowed women, and other women who did not fit the dominant image of the Bengali woman as wife and mother were excluded from the idealization that was simultaneously under construction.71

Abanindranath’s tale points to the firm linkage established between kantha and feminine virtue, thrift, and homemaking skills that were also being elaborated across multiple genres as English-educated Bengalis, both men and women, were reevaluating their domestic lives and relationships to articulate their engagement with modernity and to participate in the transnational discourses on domestic practices of the nineteenth century. A near contemporary of Kshirer Putul is the household manual Ramanir Kartavya (Duties of Women), a work coauthored by Giribala Mitra and Jaykrishna Mitra. In a section for “Making Useless Things Useful,” kantha feature in the prescriptions toward establishing domestic order:

Many women make Kantha quilts from old fabrics. . . . If you heard how the housewife of a certain family uses her kantha quilts in winter, you would be astonished! She makes many kanthas, big and small, puts quilt covers on them, and stores them away. At the start of the cold weather she gives these kanthas out to the children of the family for their use. Then when it gets even colder, she washes the covers with soap or Fuller’s Earth, puts them back on the kanthas, stores those away and in their place gives out heavier, padded quilts (leps). When, again, the cold becomes less severe, she again washes the thick quilts’ covers, store the quilts away, and once again gives out kantha quilts for use. When the cold weather has ended, she washes the old quilt covers with soap or Fuller’s Earth, gets new quilt covers washed by the washerman, and stores the kanthas away for a year. All of this housewife’s work is commendable. She is extremely thrifty; there is no hardship in her household.72

The detailed instruction for making and maintaining kantha here may be expressions of the uncertainties encountered in the navigation of everyday life at the time, the choices between older and newer ideals, objects and ways of doing things. The values of cleanliness, efficiency, and economy, and new materials, bringing to kantha the English practice of using fuller’s earth, a clay that had been used to clean wool and absorb lanolin, perhaps signals the new order that was coming into being alongside the more publicly debated concerns such as education for women.73 As embroidery came to be associated with the civilizational skills of domesticity and the character of women, it entered the repertoire of women’s education in both England and the colonies.74

Making useless things useful, moreover, acquired a political valence in the years leading up to the Swadeshi movement, the nationalist economic strategy to boycott British goods in order to promote domestic production, and the resistance to the 1905 Partition of Bengal. By 1905, domestic rituals were claimed for the nationalist cause to encourage women across a wide spectrum of classes and regions to participate alongside their reformist spouses. Ramensundar Trivedi, for example, called for arandhan, the practice of eating uncooked foods rather than lighting the kitchen fire, usually associated with rituals, such as the observance of the first day of the monsoon. It was framed in terms of a vow (brata) associated with Lakshmi, the local goddess of prosperity (Bangalakshmir brata-katha), now in the service of the nation. The goddess had to be wooed through rituals of arandhan, rakhi-bandhan (tying thread bracelets on the wrists), and abstention from foreign goods, particularly machine-made cloth. The image of a golden Bengal was concurrently envisioned as vistas of ripe rice fields and identified with the body of the goddess to counter the reality of economic privation attributed to the exploitations of colonial rule. Kantha, created for the celebration of vows in rural areas of Bengal, were thus claimed to participate in fabricating a domesticity that was both modern and patriotic.

By 1928, Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay’s Pather Panchali, one of the most popular Bengali novels from the first half of the twentieth century, had placed kantha squarely in the making of homes and selves:

In the eastern part of Horihor’s compound there was a thatched hut, which had lain unrepaired for a long time. It was there that the old woman lived. On a bamboo peg hung two dirty garments, the torn ends of which she had knotted together. She did not sew nowadays because she could no longer see to thread her needle; so when her clothes tore she tied knots in them. To one side of the room there was a frayed grass mat and a few torn baby quilts, crude patchwork affairs. Some torn clothes, which were all she had, were tied up in a bundle. It may be that she was saving them to make into another baby’s quilt. But she had no need for quilts now and even if she had her eyes were not strong enough to stitch the rags together. Yet she kept them with great care; and whenever there was a sunny day during the monsoon she took them out and aired them in the sun.”75

The emphasis on taking care of kantha, not only making or using them, had clearly become naturalized as the work and lives of women by this time. Conversely, constructing her life and her shrinking world in this way gives Indir Thakurun purpose as she ages and becomes less useful to the household, unable to make kantha any more.

The histories assembled around the same time also reinforced the association of kantha with Bengal itself. Dinesh Chandra Sen mobilized kantha for the cause of swadeshi resistance, to attain self-sufficiency through the boycott of foreign goods, particularly machine-made textiles, the making of which was recognized as a disastrous economic drain. A prominent historian of Bengali literature and founder of the Bengali department of Calcutta University, Sen dexterously wove material from his reminiscences of travels through the region in his compilation of histories of various cultural practices with the prevailing nationalist ideologies.76 In his monumental historical account, Brihat Banga (Greater Bengal, undivided Bengal), Sen’s pronouncements are succinct:

Rich was the Bengali when he did not eat sweets from the bazaar or wander through shops to find exquisitely carved wood. To make a kantha usually took six months, but we have heard of kantha that grandmothers began stitching, mothers spent a lifetime working on and passed along to their daughters to complete. These invaluable works, which are no longer to be found, hardly cost a rupee or two. The money that we spend chasing German and Japanese shiny wares would have procured ten such kantha. We are a defeated nation, but it is not political defeat that I find as regrettable as the loss of values in the misplaced maze of foreign goods.77

The power of craft is inextricably interwoven with values—the labor of love, investment of time, and connection of generations within the multigenerational family of a joint family system. Such valorization carries forward the trajectories established in anticolonial nationalist scholarship from the second half of the nineteenth century. This construction is achieved by juxtaposition with machine production. A contrast is implicitly set up with the abundance of industrialization. A subdued aesthetic and shabby genteel culture of handmade goods is endorsed over vulgar consumption, as represented by the sheen of machine-made wares. Elaborately stitched kantha are thus strengthened with moral and ethical vigor. Yet as much as he locates domestic kantha within households and the hands of multiple generations of women, Sen’s reflections also testify to an aspect of commoditization; they could become available for purchase, an observation likely based on his own encounters with such material.

Two illustrations culling recognizable elements of kantha embroidery accompany Sen’s text.78 Each is a pastiche assembled from patterns and motifs, likely drawn from his personal kantha collection, which has not survived.79 They display a deep awareness of the compositional and organizational strategies visible on kantha surfaces. They also play with the aesthetic and rhetoric of patchwork visible on many kantha surviving from the nineteenth century, with the surface segmented by elaborate patterned grids that frame individual vegetal or figural compositions. Both anchor popular kantha motifs around a central lotus, the most popular of organizational devices. Figural vignettes such as an elephant and a horse rider fill the field, along with floral and kalka (paisley) borders. The drawings simulate the deliberately pastiche-like juxtapositions of many nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century kantha, while demonstrating a range of motifs and styles.

Sen’s collection was assembled to a significant extent by the acquisitions made by Jasimuddin (1903–1976), one of his favorite students at Calcutta University. Jasimuddin himself came from rural Faridpur, a subregion that has come to be recognized as the heartland of kantha making in the nineteenth century.80 Perhaps inspired by his mentor, Jasimuddin turned to depictions of rural life and nature in his creative work as a poet, dramatist, and songwriter.81 His best-known work, the narrative poem Nakshi Kanthar Math, translated into English as “The Field of the Embroidered Quilt: A Tale of Two Pakistani Villages,” carries forward the themes of these textiles making domestic spaces, and affirming emotional ties. He contemplates the potential of reading kantha as autobiography, and kantha making as constructing the self by imposing order on life experiences and emotions (see chapter 1). At the same time, Jasimuddin gestures toward the agency of these objects. He is also prescient in recognizing the needle as no less powerful than his own instrument of choice.82

The artist Jamini Roy (1887–1972) called attention to the distinctive features of kantha on canvas. An exuberant innovator, he turned to kantha along with alpana, pata (scrolls), terra-cotta relief panels, and other local practices from his home in rural Bankura in the western corner of modern West Bengal.83 In the concerted search for forms and styles to create a new Indian art, his experiments display familiarity with the kantha themselves and careful observation of their motifs, the distinctive ways of creating motifs, and those features that were celebrated in nationalist dialogs about kantha. To simulate a kantha fragment in The World of Kantha (fig. I.16), he rendered the distinctive placing and spacing of the running stitch in opaque watercolor on an off-white background the color of worn white cotton cloth, with stains and discolorations. He selected some of the most popular motifs that survive on the older kantha from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.84 Anchoring the lower corners are kalka motifs that were immensely popular on kantha (fig. I.14, I.32), where they may have found their way from embroidered jamavar shawls from Kashmir and from Scottish woven ones. Characteristic of the symmetrical organization of most kantha, two sets of riders, a pair on elephant back and a single rider on a leopard, complement each other on either side of a flowering shrub.85 Each form is inscribed within strong contour lines in bold colors, a convention that distinguishes kantha embroidery.86 The central plant arises from what appears to be another bush at its base, with floral configurations like those at the corners of the two kantha examined in chapters 2 and 3 (figs. I.14, I.15). The translation of embroidered petals in brushstrokes mimic the careful juxtaposition of running stitches to create the tapering form of each petal opening out from the center. Painted variations in texture suggest manipulations of thickness of ply and number of embroidery threads that could have been used to stitch the fullness of the flowers. The movement achieved through striations of colors of threads from one petal to another by kantha makers is also translated through brushstrokes of contrasting colors. The shifting effect of light on textile is suggested in the careful shading of the yellow flower at the base of the plant. If such close observation of kantha offered inspiration for painting, the endeavor surely also monumentalized the textiles themselves.

I.16. Jamini Roy, The World of Kantha (ca. 1950). Opaque Watercolor on Canvas. Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art, Gainsborough, FL. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas J. Needham, 1987.1.56. Photograph courtesy of the Harn Museum of Art.

Despite the varying nuances and complexity of their engagement, these political and intellectual giants made kantha synonymous with Bengal itself. Their convictions contributed also to a craft-oriented vision of an independent India, collecting its textiles for display and institutionalizing the production of things that had once been made at home. Although kantha never acquired the profile of khadi (handspun and handwoven cloth) and the charkha (spinning wheel) in representing the struggle for economic self-sufficiency and independence from “Manchester” cloth, they quickly entered the National Museum and the National Handloom and Handicrafts Museum in Delhi, and subsequently, the National Museum in Dhaka.87 Here, they came to play a critical role in fashioning the aspirations of nascent nations. As Bangladeshi nationalism championed kantha in the resistance to Pakistan, the textiles garnered far more international visibility. High-profile NGOs infused new energy into the production and commoditization of kantha, and an era of “boutique kantha” was inaugurated.88