Читать книгу Making Kantha, Making Home - Pika Ghosh - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CANONS, CONSTRAINTS, AND MISFITS

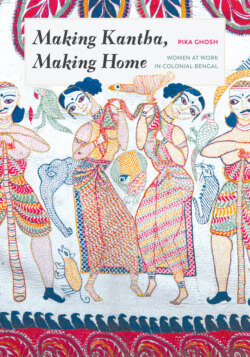

ОглавлениеA spectacular kantha found a place in Partha Mitter’s 2001 survey Indian Art, signaling the impact of the turn over the past few decades toward visual studies, material culture studies, recognition of our bodies as social and cultural constructions, and acknowledgment of alternate—particularly, gendered—perspectives, all of which have complicated art history’s canons (fig. I.14).27 The enormity of this move cannot be underestimated, and its methodological implications are immense. The attention lavished on this extraordinary embroidery in a full-page color spread, however, is somewhat undercut by the title of the book’s chapter, “The Non-Canonical Arts of Tribal Peoples, Women, and Artisans,” which points to some tentativeness in interpolating material that had previously been consigned to the interstices of the discipline, driven by the hierarchies in the prevailing categories of art and craft, classical and folk, high and low. The association with women, home, and everyday household rituals rather than the prestige of elite commissions and exhibitions, and the preoccupation with thrift and recycling rather than investment in visible grandeur and more permanent materials, thus impeded kantha from the privileged sphere of art. Although in Mitter’s volume the maker of the kantha is named and her intentions as laid out in an embroidered inscription are noted in the caption accompanying the image, the genre is not endowed with the kind of specificity and focus in the chapter’s text that we have come to expect in discussions about works of art. In general, the absence of written records to provide information about makers and the complexity and creativity in their construction undoubtedly contributed to such categorization. In Mitter’s chapter, the featured kantha fulfills the dual role of representing women’s practices and domestic art forms, along with alpana floor designs and madhubani wall painting, and serving as a segue into everyday arts and performance traditions. In turn, this assortment of material is tucked between chapters dedicated to Rajasthani and Pahari manuscript painting and British colonial art and architecture, the media and material that have come to be accepted unquestionably as art.

I.14. Manadasundari’s kantha, Attributed to mid-nineteenth century. Collected by Gurusaday Dutt between 1929 and 1939. Khulna region, in modern Bangladesh. 167 × 118 cm. Gurusaday Museum, Kolkata, (GM 1481). Photograph courtesy of Shubhodeep Chanda.

Latent in such frameworks for constructing a history of South Asian art remain the hierarchies of art and craft that had elevated painting, sculpture, and architecture, along with music and poetry, as the fine arts since at least the European Renaissance.28 These practices were estranged from “crafts,” which were related through prevailing values that included technical skill, utility, reliance upon traditional rather than innovative compositions, and more perishable media such as cloth, clay, feather, and wood.29 Over the past decades, sustained critiques of such prejudices have been mounted from the convergence of interest in these media among established artists and curators at venerable institutions, even as “craft” has become laden with additional layers of nostalgia in the explosion of digital media. Likewise, challenges have been levied across multiple disciplinary boundaries, including the anthropological scholarship on the colonial power dynamics at work in relegating craft or decorative status to particular productions30 and the imposition of hierarchies privileging vision;31 the increasing art historical commitment to more mass-produced, commercial, and popular visual and material culture;32 and decades of feminist interrogations.33 Yet the tenacity of the categories, as they resist dislocation, testifies to the power and authority at work in the global nodes and networks of artworlds to sustain particular investments. The marginal place of kantha, in fleeting displacements such as Mitter’s gesture, only affirms the hold of such stratifications.

A spate of recent exhibitions featuring Indian textiles at preeminent venues of the international art worlds, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s 2009 exhibition Kantha: The Embroidered Quilts of Bengal, the first international show dedicated exclusively to these textiles, began to put cloth and handcrafted textile traditions on the map.34 It was followed in quick succession by the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Interwoven Globe of 2013 and the Victoria and Albert Museum’s blockbuster The Fabric of India (2015). At the same time, scholarly interest in the key role of material goods and their consumption patterns in creating trade networks and imperial formations produced historical accounts that specifically examine the role of textiles in going global.35 This book engages such inquiry through a practice recognized as deeply meaningful in shaping Bengali identity—in all its heterogeneity—in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The products and practices were circumscribed by the exuberance and volatility of political ideologies in the outpouring across the literary, visual, performative, and verbal arts, as well as the rituals of everyday life. The value of these embroidered textiles as a tool for analysis thus lies in their very location, at the juncture of individual expression and social structures. The book engages the question of how kantha participate in negotiating gender, class, and urban/rural divides.36 Such repurposed fabric articles also invite reexamination of the multiple intersecting domains inhabited by textiles, thereby complicating their roles as exclusively domestic or commercial products.37

The common Bengali phrase for using a kantha, gaye deowa—to put a kantha, whether a shawl or blanket, on one’s body—alerts us to the integral and inseparable relationship of the physical body to the textile. That body, as much as the fabric, is shaped or disturbed in this relational dynamic. This is achieved through touch and texture, and sometimes through sound, smell, movement, and additional materials as well, not exclusively through sight, the physical sense that had received the undivided attention of art historians before the recent turn toward phenomenological approaches to material culture. Early scholarly writing on kantha did not entirely appreciate this vitally multisensory dimension, instead mapping a range of political agendas onto the material without taking sufficient pause to touch the cloth, feel the comfort, smell bodily odors, and hear the softest rustle of the kantha that gave rise to those qualities.38 My research returns to this critical facet of engagement with the textiles to better understand their role in the fabrication of worlds and selves. An emphasis on physical examination of the objects themselves—for clues about processes of construction, the visible choices made by makers, their use, and the perceptions about them—fleshes out and complements the earlier studies.

Their peculiar tactility and intimacy did nothing for kantha, or any other type of textiles, that would have helped it compete successfully with the prestige of painted manuscripts or sculpture. With the birth of museums as storehouses of artifacts accumulated hand in hand with the territorial expansion of British colonial power in South Asia, it was, not surprisingly, the expensive and durable materials such as stone, metal, and canvas that were more attractive. Kantha do not seem to have been coveted, at least in the early phase of conquest, even though textiles had clearly played a key role in colonial and imperial commercial interests and hence in anticolonial nationalism. The complexities of storage, restoration, and display of textiles as a medium surely deterred collecting and delayed their entry into the institutionalized spaces of display such as museums and galleries.39

Indian textiles began to garner attention as the Arts and Crafts movement gained momentum in Britain in the 1880s. Motifs and techniques of production from Britain’s colonies in South and Southeast Asia were embraced to rejuvenate the imperial center with “traditional” forms and techniques in the face of industrial production and its disaffections. They seemed to represent the security and stability of the unchanging at a time of rapid, disturbing change. They also served as repositories for the nostalgia for a pre-capitalist mode of production in which designer and executor were unified and production and consumption were not divorced.40 Ironically, the efforts of John Ruskin and Thomas Carlyle only reinforced the handicraft status of Indian textile production.41