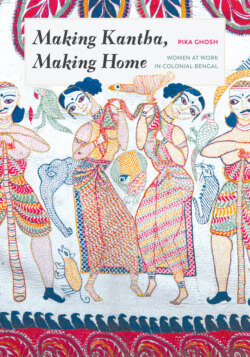

Читать книгу Making Kantha, Making Home - Pika Ghosh - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

LISTENING FOR WOMEN’S VOICES

ОглавлениеKantha have not been subjected to sustained visual analysis, nor have they been culled as material sources for women’s creativity and the rhythms of their domestic lives. This book approaches the textiles as rich visual archives for complicating our perceptions about a vibrant, tumultuous, and minutely scrutinized period in Bengali history. The project also seeks to understand the processes whereby such resonances have become steeped physically within the textiles that survive, how they have coagulated in memories and perceptions of individual fabric articles as these have been handed down, along with the objects themselves. The study thereby nuances the broad sweep of earlier writing that celebrated kantha as the fabric of nation building and the scholarly literature that constructed a canon for South Asian art.

In my earlier work on these textiles for the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s exhibition and accompanying catalog, Kantha: The Embroidered Quilts of Bengal, I encountered a range of material across homes, both rural and urban, elite and impoverished, that allowed me to appreciate the embeddedness of ordinary things in people’s perceptions of their lives and selves. I heard women say, “This is what we do.” Such pithy, matter-of-fact observations underscore how making and using kantha is so deeply ingrained in their lives that it requires no deliberation. Ordinary kantha, repurposed from discarded clothing, are used, repaired, and then recycled into cleaning rags and diapers until the base cotton fabric disintegrates beyond repair.102 These glimpses into the everyday lives of such textiles somewhat destabilized my understanding of kantha based on the examination of colonial-period material in museum storage vaults. For the most part, the latter are beautifully designed and dexterously embroidered, far removed from the patterns of mundane domesticity, if indeed they had ever participated in such daily use. Such extraordinary textiles had survived over a century either as heirlooms that anchor families, or had changed hands along the way and entered collections. As my research developed, I began to understand how the acquisition of exceptional textiles into collections, together with the practices, perceptions, and the language of the everyday, had undergirded the ideological quest for nationalist ideals in kantha from the turn of the nineteenth century. This book is, in part, an attempt to probe the relationships between the different kinds of textiles and the narratives I heard in homes to those emerging from nineteenth-century debates around art, craft, and the nation.

This study focuses on the earliest kantha that survive from the middle decades of the nineteenth century, although in my attempts to make sense of this older material, I have turned to many others created over the twentieth century that reside in homes as cherished heirlooms and in collections. For the most part, the parameters of this study are also restricted to household practices of kantha, conceived broadly. More specifically, this study turns around two objects that display some of the finest technical execution and conceptual sophistication. Yet they testify to the domestic lives of cloth articles in their imagery, inscriptions, and marks of wear and tear. They are therefore useful for pondering a particular intersection of the two ends of the divide between “high” and “low” (or “folk”) that still pervades art historical practice and the worlds of art museums and collecting despite the numerous interventions to disturb such hierarchies in the past few decades. Manadasundari’s kantha was collected by the Indian Civil Service officer Gurusaday Dutt during his travels through the Khulna region of southern Bengal (fig. I.14). It now enjoys pride of place in the museum devoted to his collection at the outskirts of Kolkata. The second, Kamala’s kantha, was acquired by the historian of South Asian art Stella Kramrisch during her time in Kolkata in the first half of the twentieth century. It came with her to America, where it graced her homes prior to its current residence in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (fig. I.15).

Although both kantha have embroidered inscriptions, neither includes a date. Manadasundari’s kantha displays carefully delineated motifs such as the official imagery on colonial-period coins and stamp paper as well as jewelry, and architectural elements that together allow us to locate it in the middle decades of the nineteenth century, as discussed further in chapter 2. Kamala’s kantha, despite its very different subject matter, reveals some fundamental compositional similarities to that of Manadasundari that suggest it was likely also created during this time. A comparison of the elaborate lotuses centering the embroidered surface of each kantha discloses that these floral forms were similarly conceptualized and executed. They indicate that the two textiles belong in a corpus of early kantha that share these elements (figs. I.29, I.30, I.31, 3.7). The lotus on each kantha consists of two overlapping rings of petals around the seedpod at the center. The inner row is comprised of smaller petals, and every two are framed by one larger outer petal. The petals, moreover, share a similar silhouette, one that is distinct from petal profiles on other dated kantha from the second half of the nineteenth century that are more angular and geometric for example, imparting a star-like shape to the flower.103 Each petal on Kamala’s kantha, and each of the outer row of petals on Manadasundari’s kantha, consists of three zones of color, contained within a bold, dark outline rendered in backstitch. Where the tips taper to a point, densely packed red stitches creates a rosy hue, which has since faded and lightened on Kamala’s kantha. The two textiles share the same approach to filling this triangular shape in backstitch, moving in concentric lines along the outer periphery of the three sides toward the center.104 The innermost section of each petal is white, rendered by the absence of embroidery stitches on Kamala’s kantha, while filled with small running stitches on Manadasundari’s. Striations composed of delicate lines of red backstitch create an intermediary zone from the red tip to white base of each petal. Beyond the outer row of petals, three rows of patterns bridge the distance to the paisleys at the periphery of the central medallion. In addition, the paisleys are also comprised similarly on the two kantha (compare figures I.32 and 3.7). Both alternate contrasting colors of threads for filling and outlining each paisley. Further, each leaf-like shape inside the paisley is embroidered in backstitch from periphery to center as in the case of the petal tips. On Manadasundari’s kantha, each paisley is supported on three prongs and filled with a stem with pairs of leaves. Kamala’s kantha elaborates on this base. These fundamental similarities, despite the divergences in each woman’s interpretation visible in the distinctive qualities of her stitchwork, indicate the likelihood that the textiles shared in the conventions circulating among Bengali embroiderers in the middle decades of the nineteenth century in the Khulna-Jessore-Faridpur area, today’s Khulna Division in southern Bangladesh.105

The two kantha also share in the practice of elegantly composed and rendered inscriptions, in marked distinction to others that do not carry any text or that bear only brief signatures stitched by original makers or added later (figs. I.32, 2.1, 3.1).106 These texts give us the name of a primary maker, even though the work must have involved some collaboration because aspects such as layering the base cloth smoothly requires more than a single set of hands, as discussed further in chapter 1. The inscriptions also hint at the conditions of making the textile. Manadasundari seems to have adhered to a common practice of making a kantha with a person or occasion in mind, although these highly malleable and mobile objects can reveal complicated perceptions of ownership and histories of use in the long run. Kamala, on the other hand, does not disclose any singular recipient or event; rather, she meditates on her relationship with her god, allowing us to locate her work in a devotional milieu of deep historical significance in the region.

These textiles have received the most scholarly scrutiny afforded to individual works of this genre, scant as that may be. The iconography of women’s work was typically not given the attention that was lavished on painting, sculpture, or architecture, the genres identified as art. Instead, embroidery, relegated to craft, was addressed predominantly in terms of style and technique. Only a rare handful of textiles, such as the Bayeux Tapestry or sumptuous Byzantine attire, have been so indulged, but the recent spurt of textile scholarship encourages such work beyond Europe. The technical dexterity and creativity displayed on these kantha make them worthy of the kind of careful visual scrutiny that characterizes art historical practice. I take the direction from their inscriptions to interpret the exquisitely detailed imagery, while recognizing that such an approach inevitably has its own problems, reifying the traditional hierarchies associated with medium rather than dismantling them.

I use the textiles to ask how far these objects can give us access to their makers, Manadasundari and Kamala, and to the particular conditions of their making and possibilities of use. Manadasundari and Kamala were like most women who stitched kantha at home, typically for use in extended household networks; if they were literate and therefore the composers of their embroidered inscriptions, they probably did not create substantial written texts, or what they did write—perhaps letters or domestic ledgers—was not deemed significant enough to save. Nor do the material worlds that these needleworkers inhabited endure to give us clues to reconstruct the worlds of their activity. Little is known of the household spaces where they worked and lived, their needles, scissors, and the boxes or containers in which they stored their tools. Yet such absences only reiterate the importance of their finished work as historical documents, as elusive conduits to their mostly unrecorded lives and aspirations.

I.29. Line drawing, central lotus medallion of Mana-sundari’s kantha (figure I.14). Prashanta Bhat, The Landscape Company.

I.30. Line drawing, central lotus medallion of Kamala’s kantha (figure I.15). Prashanta Bhat, The Landscape Company.

I.31 Central lotus blossom. Detail of Manadasundari’s kantha (figure I.14). Gurusaday Museum, Kolkata (GM 1481). Photograph courtesy of Shubhodeep Chanda.

I.32 Paisleys (kalka) around central lotus. Detail of Manadasundari’s kantha (figure I.14). Gurusaday Museum, Kolkata (GM 1481). Photograph courtesy of Shubhodeep Chanda.

This concern also takes on particular significance if we recall that these stitched accounts come from about the time when other Bengali women were writing the earliest memoirs and autobiographical accounts that survive. Juxtaposing the textiles with these texts nuances the range of women’s expressions to insert their voices into the historical record. However, the difficulties of trying to listen for such voices of women from bygone days are many. For one, a generation of scholars has cautioned us to heed the domination of the subaltern studies project in their brilliant attempts to recover experiences and identities that had previously been obscured by a historiography enamored of elite cultures.107 They paved the way for scholarly focus on gender issues and more intricate entanglements, including women’s interactions across class and race, such as the impact of European women navigating between the colonial state and local populations in India in the nineteenth century, the differentiated roles of women in addressing issues such as child marriage, for example, and oppression of one group of women by another.108

Most women who make kantha in their homes seem to agree that kantha pata— spreading the layers of fabric to smooth them with precision to the right degree of tautness to create an even surface for dense stitchwork—is one of the most difficult aspects of kantha making. To spread the finished textiles that I encountered was no less of a challenge. I had to start with the most basic decision of how to orient myself bodily in relation to objects that now reside in museum collections. Of the two kantha that are the centerpieces of this book, one is displayed vertically behind glass in Kolkata (fig. I.14), and the other is now rolled between sheets of tissue in a storage drawer in Philadelphia, retired after the 2009–10 exhibition (fig. I.15). To imagine how they could have been opened up, viewed, and used in domestic environments previously, I turned to the generations of scholars before me, the accounts left by collectors such as Dutt and Kramrisch, as well as to patterns of use today. Through such endeavors, I learned to listen for the voices of women who have left only their names and tantalizing glimmers of their ambitions in their layering of fabric, secured by embroidered images, and pithy epigraphs (kantha atkano).

I began to understand that kantha are highly dynamic, sharing the improvisational quality of the conversations themselves and embodying individual agency and relational value. They can become repositories of memories of particular makers, givers, recipients, and owners, of the specific occasions when they were made, given, used, repaired, and preserved, and of the intricate networks of relationships initiated, activated, transmuted, or even challenged in the particular contexts of giving and using. The same kantha can thus carry a host of meanings—shared, divergent, or even conflicting—for the people who encountered or engaged with it. The accrual of associations is also an ongoing process, sometimes shifting subtly or even changing more dramatically over the course of the lifetime of the kantha. Observation of these intricacies, perceptions, proprieties, and variations in living communities informs the interpretation of the two kantha, in some ways more directly, while also reminding of the many dimensions of their ephemerality and tangibility that cannot be recovered with much specificity.

The theme of negotiating the proprieties and reciprocities associated with giving gifts sheds light on Manadasundari’s kantha in chapter 2 and provides useful direction for approaching the imagery through the lead offered in the stitched inscription. The imagery and inscription further offer the opportunity to ask how these objects participate in the articulation and mediation of gender roles and expectations in gift bestowal and reception. Such considerations also yield the possibility that its maker, Manadasundari, may have sought to make her presence felt through her handiwork in ways that we are only just beginning to discern.109 Such rich textiles thus allow for a convergence of multiple approaches to the study of material culture.

Ethnographic research also helped me to home in on the reflections of several older women who have made multiple elaborate kantha over their lifetime. Mulling on their personal processes and internal rhythms in making kantha, much like the introspections of women artists from other parts of the world, indicated the need to recognize the textiles as the externalization or visualization of a process of interiorization.110 They cherished the work of their hands (hater kaj) as meditative and therapeutic. It allowed them to return to their bodies, to reintegrate themselves, to cope with losses, and to gather strength through their hands into their bodies. Such musings have inflected my examination of Kamala’s kantha in chapter 3. I employ their observations to interpret Kamala’s claim about finding her place at the feet of the gods in her inscription in concert with her choice of religious imagery. Moreover, as visualized prayers lavished by Kamala, the embroidery holds the promise of protecting beholders in their embrace. In emphasizing interiority and embodiment in my reading of this kantha, I exploit the two case studies to suggest divergent directions, although in reality, both inevitably embody both inward and outward engagements.

The significance of touch in constituting their meanings, persistent across class and region in the conversations I recorded about kantha, shapes my interpretation of these textiles in specific ways. Touch insists on the corporeal. It relies on contiguity to function, keeping an embroiderer physically and psychically connected to herself through her materials and hands while at the same time expanding her sense of self beyond. Touch can mediate between her body and the textile and what transcends it, which can be understood as a yearning for divine contact. If the gift of a kantha must have been, to some extent, a desire for proximity, for conferring emotions, it would have renewed connection and contact through touch and a world of sensation that invoked the bodies of makers and recipients. Since skin and fabric are permeable interfaces between the inside and outside of a maker’s body, Manadasundari’s touch and feelings might have been communicated through the kantha as conduit as well as through her words and choice of imagery. Likewise, the layers of cloth would have been thickened by the bodies of recipients, through contact with another set of cutaneous boundaries that are also receptive to the malleability and textures of the kantha.

In textiles of such extraordinary visual coherence, it seems safe enough to assume that individual, familial, and social dimensions would have informed, to a greater or lesser extent, the embroiderers’ choices visible in their kantha. Motifs, narratives, and compositional elements including color, shapes, sizes, and stitch types that were selected by these needleworkers from the available repertoire are sophisticated acts of interpretation of forms shared with other media such as prints and watercolors. Their versions incorporate play with colors of threads, thickness of ply, textures, and variation in motifs or patterns. They create distinctive composites that modify earlier iterations and offer up startling or innocuous sequences and juxtapositions and other organizational relationships that highlight particular nuances among elements on a square or rectangular fabric surface. Comparative analysis yields glimpses into how needleworkers interpreted, individuated, reinforced, challenged, or subverted what may have simultaneously been coalescing across multiple visual, performed, and literary genres. Some motifs take on particular significance as dimensions of lived experience in homes and families, which were inherently part of the lives of the objects themselves, distinct from their iteration in prints, Kalighat single-scene water colors, or terra-cotta reliefs on temple walls. Because many of these narratives are known from other media that are typically assumed to be male authored (both European and Indian), the distinctions in the textile renditions are discernible through comparison, and they can yield clues to a woman’s construction of these episodes within her larger vision for the textile, whether a gift, an object for personal use, or dedicated to the divine.

Kamala’s familiarity, for example, with print imagery and turns of phrases from the literary cultures of the Gaudiya tradition under construction over the second half of the nineteenth century, particularly with their increased circulation in print at this time, is discernible when compared with these other media as discussed in chapter 3.111 Her kantha thus also attests to the active role of women in claiming Vaishnavism toward Bengali nationalist self-fashioning in the nineteenth century. Such textiles participate in the resurgence of investment in Vaishnavism in response to both colonial missionary polemic and the spate of conversions among the educated upper-caste Hindus and other emergent intellectual traditions such as the Brahmo Samaj, all anxieties that fueled the quest for authenticity. Although the textual dimensions of such agendas are now better understood, Kamala’s embroidered imagery and epigraph manifests the creative engagement of erudite women in these processes.

Together, these two kantha also reveal how the interpretation of motifs shared with other media can be brought together to create an extraordinarily coherent iconographic program in embroidery and to customize an intimate universe on these domestic textiles. Such aspiration makes the two textiles exceptional in the extant corpus. The array of embroidered male and female figures in kantha, clearly differentiated by class, age, marital, and professional status, can disclose how households are imagined and families and domestic relationships negotiated in the communication from a married woman to her father. Conversely, what is not chosen for visualization on a gift that is relatively public, perhaps sent from one household to another as much as one individual to another, is equally useful for attending to the constraints of communications in the form of a textile of substantial size that was surely to be viewed by many people, perhaps on particular occasions, when meanings could potentially be further tailored to the specific conditions of each viewing act. Textile articles may create or inhabit ambiguous spaces, reinforce social proprieties, or vacillate between emotional, familial, and community registers. They might engage in shared or dissonant sensibilities that exemplify the contingent quality of notions of social relatedness, and complicate assumptions about what is intimate or personal or shared.

The domestic spaces that such textiles typically inhabited are not necessarily restrictive spaces where women were sequestered. Rather than the binaristic language of ghare baire (at home and outside), terms that gained currency from the later decades of the nineteenth century as the roles and status of women and marriage were debated publicly and legislated, it is perhaps more useful for understanding these conveniently portable things as a notional realm of shifting boundaries, shaped, in part, by multisensorial assemblages customized for various uses from daily to life-cycle rituals.112 If monumental structures such as temples yield clues to specific historical ideologies and practices of kingship, courtly culture, theology, and religious institutionalization, kantha offer equally potent material foci for recuperating perspectives on notions of home and how these, in turn, configured the contours of individual imagination and identity and constructed family lore and lineages across class and locality.

Juxtaposing materiality and imagery with strands of personal narratives reveals possibilities for unraveling the threads of seemingly discrete biographical moments to explore the half-hidden social and cultural transactions through which these textiles are empowered. With their intimate details of human relationships in and out of households, articulated in a visual vocabulary that is at once shared and an intensely personal vision, kantha thus offer possibilities for taking textiles seriously within the scope of the discipline of art history as it expands and deepens.