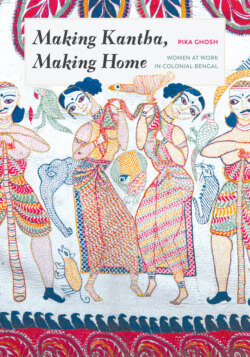

Читать книгу Making Kantha, Making Home - Pika Ghosh - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

KANTHA AND THE MARITIME TRADE IN COLCHAS

ОглавлениеThe quest for an authentic Bengali art driving early scholarship about kantha neglected the complex history of relationships between these domestic textiles and the older embroidery practices associated with the region. For example, colchas, a corpus of embroideries created with silk threads—luxury commodities for the flourishing longdistance maritime trade of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—share significant affinities with kantha in construction techniques, embroidered motifs, and aesthetic choices.89 These quilted bed covers, hangings for walls, doors, balconies, and furniture including tables, church altars, sarcophagi, and ecclesiastical vestments are best known from European collections, acquired by such luminary seafarers as Vasco Da Gama and patron figures of the Renaissance including Francesco de Medici, grand duke of Tuscany.90 Not surprisingly, relationships between kantha and these trade textiles, with their complex production processes that included transmission of underdrawings from European prints for design elements, were beyond the scope of the early nationalist scholarship that positioned kantha as repository for a pure Bengali identity and the ground for burgeoning nationalisms.91

The visual relationships between kantha and the heavy white cotton colchas were first observed by John Irwin, keeper at the Victoria and Albert Museum (1959–78). In his attempt to identify the Bengali and Portuguese elements of colchas in the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Calico Museum collections, Irwin began to discern relationships in style, aesthetic, and motifs between the two bodies of textiles, and to these he brought the terra-cotta temple imagery of Bengal to make a case for a Bengali origin for a particular subset of colchas.92 He recognized an aesthetic sensibility shared across colchas, terra-cotta panels, and kantha in the preference for grids to organize surfaces and bold outlines to articulate motifs.

Although colchas produced in Bengal were initially associated with a monochromatic palette—yellow silk chain-stitch embroidery, for the most part, on a white, undyed, cotton field (figs. I.17, I.22, I.25)—likely the legacy of the early documentation, a significant variety has emerged as recent scholarship has brought greater numbers of textiles to attention.93 These include colored background cloths such as indigo-dyed blue silk, variations in techniques for assembling the large textile surfaces, multiple embroidery stitches, and vibrant colors of embroidery threads (figs. I.18, I.27). Together, this range in technique and style points to greater visual similarities with kantha than had previously been recognized. In turn, such resonances offer the possibility of imagining bodily repositories of technical knowledge, internalized through habituated practice and distilled over generations, to begin to bridge the divide that separates the later colchas from the earliest kantha.

The expanded repertoire of seventeenth-century colchas suggests greater resonances in the organization of large embroidered textile surfaces with nineteenth-century kantha. The variety of lines, patterns, and motifs on most colchas and early kantha are marshaled to create a symmetrically balanced field (compare figures I.17 and I.18 with I.19). The majority of extant examples from both groups of textiles organize the square or rectangular surface with a prominent central motif, which is framed within panels and borders extending to the edges of the fabric. The corners are often also marked with distinctive motifs, sometimes set within roundels or variant forms. Colchas display figural motifs such as the Judgment of Solomon (fig. I.22), the pelican feeding its young, the double-headed eagle, architectural forms such as the triumphal arch, family coats of armor, and personifications of the senses.94 The motifs embroidered at each corner can feature a specific iconographic relationship to the central motif, as for example on the indigo silk colcha displaying personifications of the five senses, where one is given pride of place at the center while the four other senses mark the quadrants (fig. I.18).95 Rectangular kantha employing the lotus blossom at the center, with paisleys and flowering shrubs to anchor the corners, can suggest a similar symmetry and organization (fig. I.19).96

In its aesthetic sensibility, the embroidery on the same indigo silk colcha also shares qualities with kantha imagery. A comparison with the rendition of animals embedded within the exuberant floral field of a kantha such as that of Hemchandra Dutt reveals a common preference for dynamism and vigor through line and color choices, including the use of contrasting color outlines for forms (compare figures I.18, I.20, and I.21). The resulting elegant curves of the birds’ wings, the bold blooming floral forms, and the vitality of animals arrested in motion amid the vines create undulating rhythms of stasis and movement that invite viewers to luxuriate in their richness. Likewise, the bodies of animals and birds, often exuberantly filled with stripes, zigzags, dots, and circles on the colchas indicate that the predilection for colorful patterns was well in place before the earliest surviving kantha were created.

I.17. Colcha embroidered with yellow silk thread. ca. 1600. Attributed to Bengal. Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon, Inv. 2237 Tec. Photograph Courtesy of Direção-Geral do Património Cultural / Arquivo de Documentação Fotográfica. Photographer: José Pessoa.

Figural arrangements embroidered on kantha and colcha also reveal compositional similarities despite the aesthetic difference arising from color, material, and thickness or ply of thread, stitch type, texture, and other choices. The figure of an elegantly attired man seated in a straight-backed chair, variously enjoying dance or musical performances and imbibing from hookahs or wine cups—ubiquitous in nineteenth-century kantha embroidery—for example, shares the basic compositional elements of the seated figure of the biblical king Solomon, who is usually presented at the center of larger colchas dispensing his wisdom and just rule (compare figures I.22 and I.23).97 On these textiles created for European consumers, Solomon presides over the case, the baby offered to him by a soldier to determine which of the two women below was the mother. A similarly seated figure on Manadasundari’s kantha enjoys the company of dancers in colonial Bengal. Both seated figures engage with an attendant, extending an arm to receive an offered article. A second attendant stands behind the chair back, presumably also waiting on the seated figure. Kantha and colcha renditions often display an animal tucked in the space between the legs of the chair presented in profile. They also share a fondness for lavishly detailing furniture stitch by stitch. Other kantha versions display canopies overhead, not unlike the textile hanging above the seated Solomon (fig. I.24). Such shared elements suggest the possibility that older motifs were adapted for newer narrative purposes as these emerged to prominence. The interpretive choices to render the details including color and stitches differ significantly, thereby contributing to the coherence of distinct aesthetic sensibilities of kantha and colchas.

I.18. Indigo silk colcha featuring personifications of the five senses. Attributed to ca. 1680. Bengal. 284.5 × 218.4 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of the Friends of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1988-7-4.

I.19. Rectangular kantha with religious imagery and satirical vignettes about contemporary life. Attributed to late nineteenth century. Bengal. 165.1 × 102.2 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Stella Kramrisch, 1968-184-10.

I.20. Dappled deer and birds. Detail of colcha featuring personifications of the five senses (figure I.17). Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of the Friends of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1988-7-4.

I.21. Birds and animals framed in swirling vegetation. Detail of Hemchandra Dutt’s kantha. Attributed to second half of the nineteenth century. Bengal. Weaver Studio Collection (2011-09.0046).

I.22. Solomon with the Scales of Justice. Detail of colcha (figure I.17). ca. 1600. Attributed to Bengal. Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon, Inv. 2237 Tec. Photograph Courtesy of Direção-Geral do Património Cultural / Arquivo de Documentação Fotográfica. Photographer: José Pessoa.

Such comparisons invite questions about the transmission processes whereby forms and motifs may have been handed down over the two hundred years that probably separated the making of these two textiles. Motifs such as King Solomon dispensing justice were probably introduced to Bengali embroiderers through printed or other portable versions, particularly if the textiles were commissioned through a complex network of traders connecting Lisbon and other Iberian port towns to production centers in Hooghly and Satgaon in Bengal. These innovative compositions likely gained extensive circulation through embroideries and line drawings on cloth, and the enduring processes of bodily memory acquired in acts of repeated drawing and stitching and intergenerational transmissions from one set of hands and eyes to another. In such transmission processes inhere potential for playful variation. Not all versions of these seated males, for example, were visualized by designers familiar with rendering chairs in profile or figures seated in them.98 While Manadasundari’s babu fills his seat comfortably, others sit rather ill at ease.99 Some seem to lower themselves tentatively into the seat of straight-backed chairs, at some variance from the ambiance of leisure associated with a hookah in the hand (fig. I.24).100

I.23. Seated babu with attendant, entertained by female dancers. Detail of Manadasundari’s kantha (figure I.14). Gurusaday Museum, Kolkata (GM 1481). Photograph courtesy of Shubhodeep Chanda.

I.24. Seated man with hookah, supported by an attendant. Detail of kantha. Attributed to second half of nineteenth century. Kolkata. Gurusaday Museum, Kolkata (GM 1575).

I.25. Peacock amid vine scrolls. Detail of colcha with red embroidery. Attributed to seventeenth century. Bengal. Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon, Inv. 4581.

Interpretive choices involved in the execution of the same motif through stitch sizes, orientations, and the spaces between them also reveal similar approaches across kantha and colchas. Peacock plumage, for example, is constituted through the juxtaposition of discrete tail feathers, each composed of a single vane terminating in circles for the eye, with barbs spreading on either side. Individual feathers are then stacked adjacent to each other in rows, heeding the integrity of each feather rather than overlapping them, to fill the luxuriant tail stitch by stitch (compare figures I.25 and I.26). Within such parameters, variations abound, arising from each embroiderer’s choices for color, spacing, and ply, for example, resulting in significant differences in the overall aesthetic. The fundamental similarities in interpreting such motifs, however, suggest that ways of doing things and technical knowledge shared among embroiderers could have been handed down over the generations that separate the later colchas and the earliest kantha.

As more colchas are examined and the variety in stitchwork is uncovered, greater similarities with kantha technique and style can be discerned than was previously appreciated when colchas were associated predominantly with monochromatic chain-stitch embroidery that was densely packed to fill a motif.101 Continuous, graceful lines in back and running stitch on some later colchas, for example, when used to outline figural forms and render border patterns, can create a linear aesthetic that resembles that of some kantha embroidery (figs. I.27, I.28). Such affinities are more noticeable when the stitchwork on colchas is not used to fill inside the outline of a motif, and when thread colors are limited. It is also useful to keep in mind that from the back, both chain and back stitch resembles the running stitch closely. Consequently, as more inner layers and backs of colchas are examined, similarities with the aesthetic of continuous lines of running stitch embroidery on kantha can be recognized.

I.26. Peacock and kadamba tree. Detail of Kamala’s kantha (figure I.15). Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Stella Kramrisch, 1994-148-705.

Such resonances in construction techniques, motifs, and aesthetic belie the segregation of domestic embroideries from the travels of textiles across the vast expanses of colonial consumption and the desire for exotic luxuries. Instead, they point to a rich legacy of embroidery practices to which nineteenth-century kantha makers were heirs. The visual resonances across these corpuses suggest that Bengali women embroidering kantha in the nineteenth century participated in the knowledge accumulated over the generations that separate them from the colchas created in the seventeenth century, even if we have yet to understand the processes of transmission.

I.27. Backstitch lines in red and yellow silk thread. Detail of colcha. Attributed to seventeenth century. Bengal. Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon, Inv. 112.

I.28. Backstitch lines used to create a figure within an architectural frame. Detail of kantha. Attributed to second half of the nineteenth century. Bengal. Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection, 2009-250-13.