Читать книгу Prisoner 913 - Riaan de Villiers - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Who was Kobie Coetsee?

ОглавлениеRiaan de Villiers

‘In a sense I had, by the early eighties, already accepted that I

had this position, it was a very powerful position. History will tell whether I have abused this position, or whether I’ve used this position to bring about change.’ – Kobie Coetsee, interview with Padraig O’Malley, 26 September 1997

WHEN, ON Saturday, 29 July 2000, Kobie Coetsee died of a heart attack at age 69, the reaction in the South African media was curiously muted. Time and events had moved on, and comments came from younger politicians and others who had not been Coetsee’s contemporaries. The ‘big guns’ of the 1980s and 1990s had fallen silent.

In a Sapa report carried on IOL News, Inus Aucamp, New National Party leader in the Free State, described Coetsee as a ‘leader of outstanding talent with a brilliant intellect who played a significant role in South African politics’, without offering any insight into what that role had been.

A bit closer to home, but still without any real explanation, the NNP’s national leader, Marthinus (‘Kortbroek’) van Schalkwyk, declared that Coetsee had ‘broken the ice between then President P.W. Botha and Nelson Mandela, and understood how important it was to release Mandela’. He added that Coetsee was ‘very effective in administering his department, and also introduced the first domestic violence legislation in South Africa’.

Paul Setsetse, spokesman for Justice Minister Penuell Maduna, observed that Coetsee had worked closely with Maduna, and that his demise was a ‘sad loss for the country’. He added that Maduna and Coetsee had forged a close friendship during the Codesa talks.1 Tony Leon, leader of the Democratic Party, said he had ‘great admiration and considerable affection’ for Coetsee. The latter had reformed the institution of law in South Africa, and was a reformer ahead of his own party and era.

The Sapa report then proceeded to a biography which failed to mention the most important feature of Coetsee’s political career – his decision, while serving as Minister of Justice and later, Prisons, in the mid-1980s, to start secret talks with Nelson Mandela.2

In some ways, Coetsee’s death gained greater prominence overseas than in South Africa itself – but to no greater avail. An obituary in The Telegraph of London on 31 July 2000 started with the wild assertion that Coetsee had ‘guided the National Party in its first tentative steps towards reform, and brokered the first meeting between P.W. Botha, then president of South Africa, and Nelson Mandela’. It went further downhill from there, providing an overdramatised account riddled with errors of fact and interpretation.3

The obituary in The Guardian on 5 August 2000 was even more misguided – a surprising failure by a respected newspaper that had covered events in South Africa assiduously and quite accurately for many years. Among other things, after stating that Coetsee had ‘decided to take up a challenge’ from Winnie Mandela to ‘meet his most famous prisoner’, it went on to say, absurdly, that Coetsee’s first meeting with Mandela at Pollsmoor Prison ‘so impressed Coetsee that he soon went back for more’. One can only surmise that this obit was written by a backroom staffer who had never reported from South Africa, and had cobbled it together from files.4

Both obituaries declared that C.R. (Blackie) Swart, South Africa’s first Republican head of state, was one of Coetsee’s grandfathers, leading them to conclude that he had ‘learnt politics at his grandfather’s knee’. This is a total untruth, seemingly prompted by a clumsy sentence in a stock South African biography which the obit writers must have found online. It does, however, seem that both Coetsee’s grandfathers saw active service in the Anglo-Boer War. What can be gleaned with reasonable accuracy from these and other obituaries is the following:

Hendrik Jacobus (Kobie) Coetsee was born in the town of Ladybrand in the eastern Free State on 19 April 1931. His father, Jan, was a printer, who married Josephine van Zyl. Both were active members of the National Party (NP). Kobie was an only son. He went on to study law at the University of the Free State, qualifying with a BA LLB. In that time, he was active in the youth branch of the NP. He then practised as an attorney in Bloemfontein for some 17 years. In this period, he also volunteered for military service, and became an officer in the President Steyn armoured car regiment in Bloemfontein. In 1956, he married Helena (Ena) Malan. They had two sons and three daughters.

In 1968, he became the member of parliament for Bloemfontein West, a seat that fell vacant when J.J. (Jim) Fouché succeeded Blackie Swart as State President. In 1972, Coetsee was admitted to the Bloemfontein Bar, enabling him to practise as an advocate in the higher courts.

In 1978, he was elected as chairman of the Defence Group of the NP caucus. In the same year, shortly after becoming Prime Minister, P.W. Botha appointed Coetsee as Deputy Minister of Defence and National Security. (Botha himself held on to these portfolios until 1980, when he appointed General Magnus Malan as Minister of Defence.) In 1985, Coetsee became leader of the NP in the Orange Free State.

In this period, at Botha’s behest, Coetsee reorganised the national intelligence services in the wake of the Information Scandal, which had led to the resignation of the previous Prime Minister, John Vorster. In October 1980, he was appointed as Minister of Justice, which gave him a seat on the State Security Council. Crucially, he became Minister of Correctional Services as well.

Coetsee introduced significant legal reforms, including the small claims court system and the Matrimonial Property Act, which improved the status of married women, as well as the accrual system of sharing property between spouses. He also changed the conscription system to allow conscientious objectors, who had previously been jailed, to perform community service instead.

In April 1986, he appointed a commission to examine the role of the courts in protecting group and individual rights, resulting in a report on human and group rights that, he later believed, influenced the addition of a Bill of Rights to the South African Constitution of 1996.

From 1985 onwards, he played a seminal role in the South African transition by embarking on exploratory talks with Nelson Mandela while the latter was still in prison. In July 1989, he was present at the historic meeting between Mandela – then still a prisoner – and an ailing President P.W. Botha.

In May 1990, he formed part of the government delegation at the talks between representatives of the NP government and the newly unbanned African National Congress (ANC) which resulted in the Groote Schuur Minute. He played a major role in the constitutional negotiations from the early 1990s onwards that led to the adoption of the interim constitution of 1993.

In this period, he piloted the Indemnity Act through parliament, which granted temporary immunity to people who returned to South Africa to take part in the negotiations after the unbanning of the ANC. He also played a major role in the protracted and controversial negotiations around amnesty for people on both sides of the conflict who had committed acts of violence.

From April 1993 until April 1994, he also served as Minister of Defence. After the 1994 elections, he was elected as president of the Senate, with the support of the ANC and other parties, and held this position until 1998. In that year he retired, supposedly to pursue his hobbies of hunting, shooting and fishing, and he died two years later.

This still does little to explain the ambiguities and opacities that perpetually seem to surround Coetsee. For this, we need to turn to comments by some of his contemporaries.

First up is P.W. Botha. ‘The Big Crocodile’ appointed Coetsee as Deputy Minister of Defence and of National Intelligence, and then to the senior cabinet posts of Minister of Justice and Correctional Services. Coetsee later said they had worked closely together for many years, and he believed they trusted one another. However, following Coetsee’s death, Botha was surprisingly equivocal about their relationship.

Following its grandiose opening paragraph, the Telegraph obituary referred to earlier went on to say that, by 1985, Botha’s government had ‘conspicuously failed’ to quell black unrest, and the South African economy was under siege. Coetsee’s ‘damascene conversion’ came that year when Winnie Mandela persuaded him to meet her husband, who, while still a prisoner, was in a Cape Town hospital recovering from a prostate operation.

Coetsee was immediately impressed by Mandela, whom he likened to ‘an old Roman citizen, with dignitas, gravitas, honestas, simplicitas’. The two men struck up an unlikely friendship, and several further encounters followed in Pollsmoor Prison where Mandela was confined, leading eventually to the meeting between Botha and Mandela in 1989. (Much of this is either incorrect or oversimplified, but that is not directly relevant here.)

According to the obit, Mandela called Coetsee a ‘reformer ahead of his time’. Botha, however, was inclined to denigrate Coetsee’s contribution to the reform process, calling him a ‘funny little man’. ‘I always felt after talking to him,’ Botha was quoted as saying, ‘that it was a case of confusion worse confounded.’ The source of this comment was not cited.5

While the source of Coetsee’s remark about Mandela was also not provided, it was drawn from an interview with Coetsee by John Carlin, South African correspondent for the leading British newspaper The Independent from 1990 to 1995. Generally credited with being one of the most capable foreign correspondents to cover the transition to democracy, Carlin distilled his experiences into two books. In Knowing Mandela (2013),6 Carlin offers a personal account of Mandela, based on their relationship which developed in the period from 1990 to 1995 and thereafter, as well as research conducted during his spell in South Africa. This includes in-depth interviews with 24 role players in the South African transition. The interviews have been collected under the theme ‘The Long Walk to Freedom of Nelson Mandela’, related to a television series Carlin helped to make, and are available online.7

This resource shows that The Telegraph got the quote by Coetsee about Mandela slightly wrong as well. In the full-length interview, Carlin records Coetsee as saying: ‘I have studied the classics, and for me, he [Mandela] is the incarnation of the great Roman virtues of gravitas, honestas, dignitas. Everywhere and anywhere, where people choose people, you can’t help but choose Mandela.’ In Knowing Mandela, Carlin recounts that, while saying this, Coetsee was ‘shedding tears’.8

Then, however, with surprising rancour, Carlin describes Coetsee as a ‘small man whose place as a trusted member of the P.W. Botha court owed more to the fawning obsequiousness he showed the Big Crocodile than to any great intellectual merit or originality of thought. He fancied himself a bit of a classicist, and enjoyed flaunting his knowledge of Ciceronian discourse among his decidedly unlearned cabinet colleagues.’9 Nothing in his interview with Coetsee seems to justify this snide observation. However, it emerges that Carlin was not the only person whom Coetsee rubbed up the wrong way.

At least the Telegraph obit was more accurate about Mandela; indications are that he was well disposed towards Coetsee, and remained so in later years. In Long Walk to Freedom (his famous autobiography, revised and partly ghost-written by the American journalist Richard Stengel), Mandela recounts his secret meetings with Coetsee and the process surrounding them in some detail, but without commenting on Coetsee personally. His only remark about Coetsee appears in a passage where he writes about being moved, in December 1988, to a cottage in the grounds of the Victor Verster Prison outside the Western Cape town of Paarl, a ‘halfway house between prison and freedom’.

On his first day there, he writes, he was visited by Coetsee, who brought a case of Cape wine as a housewarming gift. ‘He was extremely solicitous, and wanted to make sure that I like my new home … He told me the cottage … would be my last home before becoming a free man. The reason behind this move, he said, was that I should have a place where I could hold discussions in privacy and comfort.’10

(While the cottage might have offered more comfortable surroundings for Mandela’s discussions, they certainly weren’t going to be private. As recounted in greater detail elsewhere, the house and garden were bugged, and many of Mandela’s conversations with his stream of visitors were recorded and transcribed.)

A longer, unedited version of this account appears in Nelson Mandela: Conversations with Myself (published in 2010), a selection of items from Mandela’s personal archive, including the unedited transcripts of 70 hours of interviews with Stengel. This passage reads:

The following day, in the afternoon, Kobie Coetsee, the minister of justice, came and … wanted to know how this building was – the house – and went from room to room inspecting it. We went outside inspecting the security walls, and he says, ‘No, these security must be raised’ … He was very careful and he … wanted to make sure that … I was comfortable, and he also brought me some nice, very expensive wines … He was very kind, very gentle, and then he told me … ‘No, we’ll move you here. This is a stage between prison and release. We are doing so because we hope you’ll appreciate it. We want to introduce some confidentiality in the discussions between ourselves and yourself.’ And I appreciated that. That’s what happened …11

At least, even according to the actual interview, Coetsee did not tell Mandela that his ‘discussions’ with his interlocutors would be private.

Next up is F.W. de Klerk, who succeeded Botha as State President some six weeks after the latter’s meeting with Mandela, and eventually released Mandela in February 1990. (Botha had suffered a stroke and, after initially relinquishing the party leadership while holding onto the presidency, was eventually ousted when most of his cabinet turned against him.) In his autobiography, The Last Trek: A New Beginning (1998), De Klerk writes intermittently about his interactions with Coetsee, in his characteristically deliberate and measured style.

Soon after becoming leader of the NP in the Transvaal, De Klerk recounts, he attended a cabinet team-building and planning exercise at a remote Defence Force base on the border between Namibia and Angola. At some stage, ‘elements within the security establishment’ mooted the idea that, if all other options for constitutional reform were exhausted, the government should suspend the existing constitution and rule by decree. ‘I vehemently opposed this idea, and was strongly supported by other senior members of the cabinet, including Chris Heunis and Kobie Coetsee.’12

He also writes, again with seeming approval, that, as Minister of Justice, Coetsee always insisted that all the government’s actions, especially during the states of emergency, should be taken in strict compliance with the law, and he had ‘even established a legal centre’ to assist them in doing so.13

In 1986, he notes, Botha proposed the formation of a National Statutory Council as a forum for negotiations with black South Africans. However, it never got off the ground. Neither Chris Heunis, as Minister of Constitutional Development, nor himself, then leader of the NP in the Transvaal, was informed of the exploratory discussions with Mandela which were being conducted by a few senior officials as well as Coetsee.14 However, he later writes, again with tacit approval, that Coetsee had cleared the meeting between Mandela and Botha with him beforehand, in his capacity as leader of the NP.15

When, in the course of the constitutional negotiations, tensions developed around the release of political prisoners, De Klerk was persuaded ‘with the greatest reluctance’ to change his initial position. Coetsee was bitterly upset when he learnt about the decision, as he wanted to use this issue as a bargaining chip with the ANC. ‘He came to see me, and offered to resign. I assured him that he was a valued member of our team, and that he had an important role to play. He agreed to remain in the cabinet.’16 Later, in his only personal remark about Coetsee, De Klerk remarks drily that the latter was ‘renowned for playing his cards close to his chest’.17

In an interview with Carlin, De Klerk reiterated that he did not participate in the behind-the-scenes discussions with Mandela, and was not briefed about this process when it began. Immediately after becoming party leader in February 1989, he was briefed by Kobie Coetsee, and from then onwards he was ‘fully part of the whole process’. He had prior knowledge of the meeting between Botha and Mandela. It had his approval, and from the start of his presidency, the release of Mandela and other political prisoners was ‘very high’ on the agenda.

Seemingly trying to get him to discard his reserve, Carlin asks: ‘You say in your book that when Kobie Coetsee did tell you about these talks … you weren’t critical, but you were surprised …’

Holding his line, De Klerk replies: ‘Surprised in the sense that I had not been informed, inquisitive and surprised that such a high-profile person would be negotiating from jail, and asking myself to what extent Mandela would have a mandate to do so …’

He was eventually told that after initial discussions, some rules had been relaxed and Mandela was allowed to have ‘certain interactions’ in order to obtain a mandate and keep his power base informed about what he was doing. ‘Obviously, I found that acceptable, because you can’t just deal with an individual without a mandate. It would have limited advantages, whereas if he were properly mandated, it would have far greater implications, and hold much more promise.’18

From 1989 to 2005, Padraig O’Malley, an Irish academic and mediator specialising in the problems of divided societies, notably Northern Ireland and South Africa, amassed many hours of interviews with role players in the South African transition. Entitled ‘Heart of Hope’, the O’Malley Archive is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory, and is available online.19

O’Malley interviewed De Klerk no fewer than six times between 1995 and 1999, and questioned him about Coetsee in their penultimate session, in July 1998. After playing a major role in opening up a dialogue between the government and Mandela, O’Malley suggested, Coetsee seemed to have ‘disappeared off the screen’, and became ‘more of an opponent of some of the elements of the settlement that was reached than a proponent’.

De Klerk said he would not say this. Coetsee was accused of having failed to negotiate a more favourable amnesty situation (presumably for members of the South African security forces). It was true that the amnesty negotiations had stumbled from time to time, which led to certain measures being written into the transitional constitution that should have been negotiated in greater detail. However, the ANC had delayed this deliberately. This was the issue that almost scuttled the peace conference, and triggered the infamous clash between De Klerk and Mandela at Codesa.

Many people, including NP members, blamed Coetsee for the outcome of the negotiations around amnesty, and Coetsee had become a controversial figure. However, De Klerk would not say that Coetsee opposed the eventual agreements. After the elections, Coetsee was made president of the Senate, with the support of the ANC. ‘Even now, there’s a very good relationship between him and Mandela. He is one of the few NP former high-profile figures that Mandela never said anything negative about.’20

But comments about Coetsee by another key role player in the transition enter a different landscape. Besides Coetsee, Dr Niël Barnard, head of the National Intelligence Service (NIS) from 1979 to 1992, played a major role in the secret talks with Mandela. In an interview with Carlin, he portrayed Coetsee and his role in changing the dynamics around Mandela in a reasonably favourable light. Coetsee, he said, had been ‘critically involved’ in the view that Mandela had to be prepared for life after prison, and leading the country. ‘So Kobie Coetsee was responsible, as far as I can recollect. Let’s now move Mr Mandela from Pollsmoor to Victor Verster … so that he can live in a normal house, so that he can gradually prepare himself for life after prison.’21

In Secret Revolution: Memoirs of a Spy Boss, however, the notoriously abrasive Barnard takes a different tack. He now claims that P.W. Botha asked him (Barnard) to head the ‘small government team’ tasked with undertaking exploratory talks with Mandela. At that time, he and the NIS were ‘entirely unaware’ that Coetsee had already held numerous conversations with Mandela. He had regularly seen Coetsee, especially at meetings of the State Security Council, but he had ‘never uttered a word’ about his earlier discussions with Mandela.

Barnard then writes: ‘Why he handed over this task – or whether it was taken away from him – we will probably never know. He was often involved in all sorts of plans and schemes which only he understood. Nevertheless, Coetsee was an intelligent man, and I am convinced that he wanted the conversations to continue, but perhaps he did not have the time or the stamina for it himself.’22

The gloves really come off in the course of three interviews with Padraig O’Malley. In the second interview, in November 1999, Barnard lambasts Coetsee for his role in the problems surrounding the amnesty process. According to Barnard, during the talks prior to the Pretoria Minute in August 1990, agreement was reached on amnesty across the board. However, at the last minute, Coetsee persuaded F.W. de Klerk that this was the wrong approach, and the issue was then omitted from the final formulation of the Minute.

Barnard then goes on to say: ‘To a certain extent … all the difficulties that we to this day have with amnesty were the responsibility of one Kobie Coetsee, who thought that he could think about weird and wonderful ideas. I think when you’re in a process like this and you get an opportunity, you must have a big mind and move as quickly as possible.’

O’Malley: ‘What were his objections [to a blanket amnesty]? This was like wiping the slate clean.’

Barnard: ‘I think that’s one of the issues which one must ask him. He’s a very strange man.’23

However, it’s in his first interview with O’Malley, in September 1998, that Barnard really puts his cards on the table.

O’Malley: ‘You have said that the role Kobie Coetsee played in the process has been greatly over-exaggerated. Could you put that into some context for me?’

Barnard: ‘I will. First of all … he tried to take the line that he was basically the man who had been orchestrating this whole exercise. I think the answer is no. Secondly, if you would have listened to what Mr Botha has been saying, he certainly didn’t command the kind of influence with Mr Botha which he said he did. With a lot of respect, I had to convince Mr Botha, finally, to see Mr Mandela, in person, alone, myself, not Kobie Coetsee, because at the time it was becoming extremely critical and I told Mr Botha in my view if you look at the history of this country you cannot lose if you see Mr Mandela.

‘If it’s a successful meeting and you can lay the foundation for the future political negotiation of this country, you would always be able to say that historic meeting between me and Mr Mandela paved the way, laid the foundation for the present political dispensation in this country, I opened the doors finally, I saw him, I started the discussion. If it is not successful, quite obviously you would be able to take the line, I saw Mr Mandela, it became clear to me that it was not possible to find a solution, I am telling this to the public, I tried, it doesn’t seem to me to be possible, so I cannot help you. So there is only a so-called win-win situation. See the man now so that we can take the process forward …’

At the root of Barnard’s issue with Coetsee, then, was a rival claim to ownership of the secret conversations which laid the foundation for Mandela’s release and, ultimately, his presidency.

Tony Leon, who rose meteorically in white opposition politics from the mid-1980s onwards, and later led the official opposition in parliament for a period of eight years, recalls his experiences of Coetsee in his political biography entitled On the Contrary: Leading the Opposition in a Democratic South Africa (2008). Among other things, it contains a brilliant, often disconcerting, account of the confused and brutal political environment of the late 1980s and early 1990s, as well as the often chaotic constitutional negotiations.

He writes: ‘In my capacity as DP justice spokesman, I had got to know Coetsee reasonably well. However, no one (not even his wife, I sometimes suspected) really knew him at all. He seldom revealed his true thinking on matters, and managed to literally smile and wink his way out of many tight corners. However, he was certainly a reformist Justice minister and had the trust of De Klerk. He had been P.W. Botha’s first line of contact with the imprisoned Nelson Mandela, and his close proximity to Mandela and his then wife, Winnie, had also (in my view) led to her under-prosecution for very serious crimes.’24

He then recounts how, to his astonishment, in the course of the constitutional negotiations at Kempton Park, Coetsee leaked to him a draft agreement between Coetsee and the ANC legal negotiator Dullah Omar to the effect that all the Constitutional Court judges would be appointed by the President and cabinet. ‘In other words, the lynchpin of the new legal order would be open to blatant political manipulation, at the level of selection at least, and would simply ape the discredited appointment mechanism of the past. However, this court would be entrusted with far greater and more sweeping powers than any other in South Africa’s history.

‘In terms of the ANC–NP agreement (which I was to learn later, with some stupefaction, had been authored by Coetsee himself), the cabinet, with a likely and hefty ANC majority, and the president, undoubtedly Nelson Mandela, would handpick their own judges! Dumbfounded as I was by the agreement Coetsee had authored and agreed to, I was even more perplexed as to why he was the whistle-blower on his own compact.

‘I later learned that certain of Coetsee’s cabinet colleagues whom he had not consulted before inking his signature to the agreement were appalled at what he had done. He was clearly looking for an escape hatch, and while he would oscillate in all directions over the next few days, blowing both hot and cold on the document, he had apparently decided that I constituted the best getaway vehicle if he needed to resile from his commitments.’

Leon went on to launch a vigorous campaign to overturn the deal, proposing instead that Constitutional Court judges should be drawn from recommendations submitted to the cabinet by a Judicial Service Commission comprising members of government, the judiciary, and the independent legal profession. A political mini-storm ensued, in which Coetsee continued to play an uncertain role.

‘Die Burger, normally the staunchest NP press ally, thundered against Coetsee and claimed in a shattering editorial that his proposal amounted to the “castration of the constitution”. This, and the undoubled internal pressure mounting against him in his own ranks, led finally to Coetsee dropping his legendary equivocation. We were now, finally, on the same track.’

On Wednesday, 17 November 1993, with the midnight deadline for an agreement approaching, negotiations reached a frantic pitch. Cyril Ramaphosa finally agreed that the judges would be nominated by the Judicial Service Commission, and the President could not add any other candidates. More horse-trading followed; at around midnight on Wednesday, 17 November, the ‘much delayed and deeply contested draft constitution was put to the full plenary of the negotiations process, and passed with acclaim’. Leon writes that he felt a sense of relief and accomplishment, and that his ‘fifteen minutes of fame’ were widely appreciated.

The next day, Thursday, 18 November, provided De Klerk and Roelf Meyer with a ‘major hangover’ when, at a 7 am cabinet meeting, senior members of De Klerk’s cabinet, including Tertius Delport, revolted against the terms of the constitutional agreement. A private discussion followed, in which De Klerk aimed to bring Delport and five or six other cabinet members on board. But things got even worse. Delport grabbed De Klerk’s lapels, exclaiming: ‘What have you done? You have given South Africa away.’ Eventually, De Klerk managed to preserve his cabinet’s unity. When parliament met the following week to debate the new constitutional agreement, De Klerk was ‘enraged’ when Leon suggested that the constitutional talks had finally put the lid on the NP’s coffin.

Leon recounts one last, poignant encounter with Coetsee: ‘Towards the end of 1999, I was in Bloemfontein when I received a call from Kobie Coetsee, by then retired from politics and again living in the city. He wanted to discuss a matter with me. We arranged to meet in the VIP lounge at the airport, shortly before my departure to Cape Town. I had always found the former minister of Justice elliptical and impenetrable; this meeting was no exception. He expressed deep concern about the ANC’s intention to “damage the constitutional settlement”. “We” should collaborate in its defence – but there were no specifics.

‘I went on to ask him what he had made of the TRC’s statement about the “strategic decisions with regard to the prosecution of Madikizela-Mandela” [for her alleged complicity in the killing of the young activist Stompie Seipei] being influenced by the “political sensitivities of this period”. He gave no direct response, simply fixing me with his sphinx-like smile. We were never to meet again – a few months later he died, on 29 July 2000.’25

It would be untrue, however, to say that Coetsee remains a total enigma. He was also interviewed by O’Malley on four separate occasions, over several years. He seemingly trusted O’Malley, and spoke to him candidly and at some length. It seems safe to say that he probably went some way towards saying the things he intended to record in his memoirs, which he was then working on but later abandoned.

Among other things, those conversations went far deeper than Carlin’s single interview, and reveal Carlin’s malicious comment about Coetsee to be materially misguided. Specifically, his conclusion that Coetsee was a person of ‘limited intelligence with no great capacity for original thought’ was quite incorrect.

Over the years, and at a distance, Coetsee emerges from these transcripts as a highly intelligent person who, in the course of a long career in some of the most important portfolios in the NP government from the late 1970s to the early 1990s – including defence, security, justice and prisons – built up a deep knowledge and understanding of the complex political processes that played themselves out in those key state functions in that period.

The interviews provide significant insights into Coetsee’s own beliefs and motivations; for instance, he says, he realised in the mid-1970s that separate development was both immoral and unviable. He continued to work in the NP, though, as he realised that ‘you can’t change anything if you’re not there’. He then went on to a sustained effort to ‘swap the sword for justice’.

The interviews also provide a fascinating insight into the real drivers of the NP government’s impetus towards reform, largely under P.W. Botha, from whom Coetsee took his orders, which have been widely misunderstood and undervalued.

However, in the ebb and flow of Coetsee’s conversations with O’Malley, interrupted and resumed over several years, they never got around to talking in detail about his activities in the crucial period from the mid-1980s onwards, when the conversations with Mandela began and the foundation was laid for his eventual release. Whether by accident or design, Coetsee said nothing about his massive, partly secret archive or the fact that it contained transcripts of many conversations between Mandela and his visitors over a period of six years – or that surveillance of ANC negotiators continued well after 1990, into the constitutional negotiations.

Or did he? The transcription of the O’Malley interview on 5 September 1998 contains a tantalising passage. O’Malley asks Coetsee whether he agrees that the NP was a pushover in the constitutional negotiations or, in the journalist Patti Waldmeir’s words, ‘the Boers gave it all away’.26 In response, Coetsee says one has to look at areas where the NP negotiators succeeded.

This includes the issue of whether or not the provinces should be retained. He then claims that Cyril Ramaphosa and Roelf Meyer had agreed that there would be no provinces, but that they might be considered at a later stage. Stalwarts in the NP (which seemed to include Coetsee) went to F.W. de Klerk and threatened to walk out if he did not dig in his heels. De Klerk agreed, and the provinces were retained. ‘We succeeded also because we read the innards of the ANC correctly, that there were more people that would feel safe within the provincial structure than there were people who would feel safe outside.’

O’Malley: ‘How did you come to that conclusion?’

Coetsee: ‘That is a different story, my friend, that is a different story, and I’ll tell it to you one day.’

He goes on to say that he was a spokesperson on this issue, and by then he had become annoyed by the way in which ‘certain things’ were lost by the wayside through backroom deals. He was certain the ANC would agree to provinces, even when Ramaphosa and Meyer had agreed that there would be no provinces, but they could be reintroduced at a later stage. ‘We pushed and I pushed, knowing that there would be forces inside the ANC that would accept it.’

O’Malley: ‘How did you know there were forces within the ANC that would accept [this]?’

Coetsee: ‘I’m just saying to you that I knew. I don’t think it’s necessary for us to record this at this point of time. But I knew. And we pushed and we succeeded.’

Lastly, the O’Malley interviews also go some way towards explaining why people found Coetsee so exasperating. He does indeed talk in an elliptical way, while also switching freely between topics, and moving backwards and forwards in time. At times, O’Malley too is confounded. Amusingly, Coetsee reveals that he is well aware of his trademark style and its power to annoy and confuse, that he derived pleasure from this, and deliberately used it to his political advantage. All this comes together in a single passage. Coetsee tells O’Malley that, at some (typically unspecified) point (but presumably in the early 1980s), he received visits from two opposition luminaries: Helen Suzman, veteran liberal parliamentarian, and Frederik Van Zyl Slabbert, leader of the Progressive Federal Party, then the official opposition in parliament. Suzman spoke to him about releasing Mandela, and Slabbert about releasing dissident Afrikaner poet Breyten Breytenbach. He hints that they influenced his political thinking.

Eventually, he told them that, with the approval of P.W. Botha and the cabinet, he was going to change the policy relating to the release of ‘security prisoners’, as he called them. He would announce this in an extended committee session of his vote – Justice and Prisons – in the Senate, instead of the more prominent House of Assembly. He would announce that ‘there’s going to be a change in policy, and I stipulated the conditions which will lead to the release of Mr Mandela, although I’m not going to announce that as such. But the first person to benefit would be Breytenbach …’

He contacted Slabbert and told him there was one condition, namely that he and Suzman should not be ‘jubilant in the press’. Botha did not want to be embarrassed. And he would always honour them (Slabbert and Suzman) for honouring the agreement – ‘they listened to me, they walked out, not a smile on their faces, knowing that this was the beginning. And you must get Hansard of my announcement there, and you will see it was couched in a style which people say belongs to me, you couldn’t read it there but it was there. You understand what I’m saying?’

O’Malley (clearly confounded): ‘This was on the release of Breytenbach.’

Coetsee: ‘Yes, but it was changing just the policy, and the rest followed … The press wrote a few lines on it, they didn’t realise what they were writing, and I enjoyed the situation …’

What is beyond doubt is that Coetsee decided to start talking to Mandela, albeit under a general brief from P.W. Botha to resolve the growing problems surrounding ‘security prisoners’, comprising mounting legal claims and court cases as well as rapidly escalating international pressure on the one hand, and pressure from the Breytenbach family – who knew Botha – on the other. Added to this, as F.W. de Klerk later remarked, long-term ‘security prisoners’ were due for some kind of parole in any case. The only sticking point was whether they would continue to advocate political violence after their release.

In this context, the Coetsee archive also reveals, quite startlingly, that Coetsee proposed the unconditional release of Mandela and numerous other ‘security prisoners’ to the State Security Council in December 1984 – four years before Mandela met P.W. Botha, and five years before he walked out of Victor Verster Prison.

It seems clear that Coetsee (assisted by his prisons management team) took the initiative to move Mandela into separate quarters in Pollsmoor Prison, away from his colleagues, thereby creating space for more uninhibited talks with government representatives, as well as the later decision to move home to a cottage in the grounds of Victor Verster Prison, a ‘halfway house between prison and freedom’. While this might have been with Botha’s knowledge – and could hardly have happened otherwise – it attests to the autonomy and room to manoeuvre that Coetsee had appropriated. And after those steps, there was no turning back.

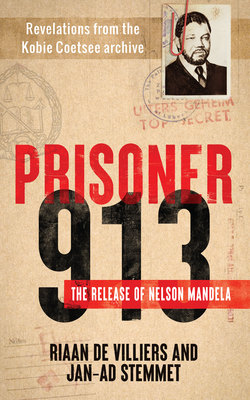

Coetsee spoke to O’Malley (and perhaps Patti Waldmeir) more freely than to anyone else. At the same time, there is no record of him disclosing to anyone that he had created an extensive surveillance apparatus around Mandela, and monitored his conversations in prison for a number of years. This remained a secret until 2013 when, as recounted elsewhere in this volume, the historian Jan-Ad Stemmet opened the first of a stack of cardboard boxes containing Coetsee’s papers at the Archive for Contemporary Affairs (ARCA) at the University of the Free State.

As noted previously, monitoring conversations with at least some ‘security prisoners’ was standard practice. Moreover, in the light of Mandela’s unique and growing stature, a degree of additional surveillance could have been expected. But why the 913 file (Mandela’s real prison number) assumed such massive proportions, and what exactly Coetsee sought to achieve by building it, remains a mystery. Given this, the archive itself – with its startling revelations, unexplained gaps, and remaining mysteries – may well be Kobie Coetsee’s most fitting and lasting legacy.