Читать книгу Prisoner 913 - Riaan de Villiers - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеThe missing letter to P.W. Botha

‘The simple fact is that you are South Africa’s head of government, you enjoy the support of the majority of the white population, and you can help change the course of South African history …’

THE ORIGINAL LETTER to P.W. Botha, in Mandela’s ornate handwriting, resides in the Coetsee archive. Besides Mandela, it was signed by Ahmed Kathrada, Walter Sisulu, Andrew Mlangeni and Raymond Mhlaba. At this point, however, Long Walk to Freedom presents the reader with a curious puzzle. Mandela refers to a letter in a single sentence: ‘Winnie and Ismail were not given permission to visit for a week, and in the meantime I wrote a letter to the foreign minister, Pik Botha, rejecting the conditions for my release, while also preparing a public response.’1

While Mandela might conceivably have written to R.F. (Pik) Botha, this is unlikely, and no such letter has ever turned up. What seems to have happened is that, when Mandela spoke about the letter to P.W. Botha, he was misunderstood by his ghost-writer, Richard Stengel. If this is the case, it is odd that, despite the editorial resources lavished on Long Walk to Freedom, this error was never detected and rectified. Secondly, Mandela omits to mention that the letter was ostensibly a joint effort, written by himself as well as his four colleagues in Pollsmoor Prison. In contrast to ‘My Father Says’, he also does not quote from it.

However, indications are that, at that time at least, he did regard the letter as significant. When Helen Suzman and a fellow member of parliament, Tiaan van der Merwe, visited him at Pollsmoor Prison more than a year later, he told them that, after Botha had made his offer of conditional release, he also replied to him in writing. (This also speaks to the agonisingly long time frames and restrictions Mandela then had to endure in the course of communicating with the outside world.)

Permission to give a copy to Winnie Mandela was refused. According to the covert transcript of the conversation, he then told his visitors: ‘That letter would have exposed the government. They suppressed it. We said we were prepared to negotiate. He [Botha] says the opposite.’ He added that this was what Botha had told the Commonwealth Eminent Persons Group (EPG), which had visited South Africa in the interim.

////

If Mandela did regard the letter as important, it was with good reason. It differs substantially from the statement read out at the Soweto rally. Among other things, it contains a virulent attack on P.W. Botha. It condemns his offer as ‘ … no more than a shrewd and calculated attempt to mislead the world into the belief that you have magnanimously offered us release from prison which we ourselves have rejected. Coming in the face of such unprecedented and widespread demands for our release, your remarks can only be seen as the height of cynical politicking …

‘… No self-respecting human being will demean and humiliate himself by making a commitment of the nature you demand. You ought not to perpetuate our imprisonment by the simple expedient of setting conditions which, to your own knowledge, we will never under any circumstances accept… .

‘… It would seem that you have no intention whatsoever of using democratic and peaceful forms of dealing with black grievances, [and] the real purpose of attaching conditions to your offer is to ensure that the NP should enjoy the monopoly of committing violence against defenceless people …

‘… You say you are personally prepared to go a long way to release the tensions in inter-group relations in this country, but that you are not prepared to lead the whites to abdication. By making this statement you have again categorically reaffirmed that you remain obsessed with the preservation of domination by the white minority. You should not be surprised, therefore, if … the vast masses of the oppressed people continue to regard you as a mere broker of the interests of the white tribe, and consequently unfit to handle national affairs …

‘… You state that you cannot talk with people who do not want to cooperate, that you hold talks with every possible leader who is prepared to renounce violence. Coming from the leader of the NP this statement is a shocking revelation as it shows more than anything else, that there is not a single figure in that party today who is advanced enough to understand the basic problems of our country who has profited from the bitter experiences of the 37 years of NP rule, and who is prepared to take a bold lead towards the building of a truly democratic South Africa …’

Botha is also taken to task for his adverse response to allegations at the UN that Mandela’s health had deteriorated and that he was being detained under inhumane conditions: ‘There is no need for you to be sanctimonious in this regard. The United Nations is an important and responsible organ of world peace … Its affairs are handled by the finest brains on earth, by men whose integrity is flawless. If they make such allegations, they do so in the honest belief that they were true …’

However, the letter also spells out the ANC’s formal demands at the time, namely that the government should itself renounce violence; dismantle apartheid; unban the ANC; free all those who had been imprisoned, banished or exiled for their opposition to apartheid; and guarantee free political activity. These are presented as steps to be taken by Botha and his government if a ‘looming confrontation’ is to be averted, and amount to Mandela’s (and possibly the ANC’s) conditions for a peaceful settlement of the South African conflict. These same demands – formulated in a less formal way – are also embedded in Mandela’s statement read out at the Soweto rally.

Most significantly, though – as suggested by Mandela in his conversation with Suzman and Van der Merwe – the letter also contains a definite feeler in the direction of engagement. In a marked shift in tone, it states:

‘Despite your commitment to the maintenance of white supremacy, your attempt to create new apartheid structures, and your hostility to a non-racial system of government in this country … the simple fact is that you are South Africa’s head of government, you enjoy the support of the majority of the white population and you can help change the course of South African history. A beginning can be made if you accept and agree to implement the five-point programme on pages 4–5 of this document. If you accept the programme our people would readily cooperate with you to sort out whatever problems arise as far as the implementation thereof is concerned.

‘In this regard, we have taken note of the fact that you no longer insist on some of us being released to the Transkei. We have also noted the restrained tone which you adopted when you made the offer in Parliament. We hope you will show the same flexibility and examine these proposals objectively. That flexibility and objectivity may help to create a better climate for a fruitful national debate.’

This passage is carefully worded; for instance, use of the word ‘negotiate’ is avoided. However, in line with Mandela’s remark to his Progressive Federal Party visitors, it signals an unmistakable invitation to Botha to engage with the ANC. It is equally startling today to realise that the NP government eventually met all or almost all of those conditions.

////

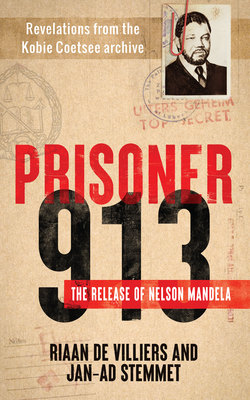

Whether the letter ever reached Botha is unknown, and if it did, so is his reaction. Maybe Coetsee decided it was too provocative, and never gave it to him. The only annotation on the letter itself is ‘Bêre 913’ (‘Place in the 913 file’). If Botha ever read the letter, he never commented on it in public.

In February 2010, the Nelson Mandela Foundation staged a commemoration of Mandela’s rejection of Botha’s offer of conditional release. To mark the occasion, the Foundation interviewed Zindzi Mandela, who had read out the ‘My Father Says’ statement. She recalled: ‘I wasn’t worried about us on stage, but I was nervous because Mummy [Winnie Mandela, who was banned to Brandfort at the time] was in the crowd with a scarf on her head, cheap sunglasses, no make-up, and looked like an ordinary aunty from the township, because she insisted on being there.’

The Foundation also interviewed Ahmed Kathrada, who described how Mandela’s response to Botha’s offer was crafted. The item on the Foundation website quotes him as saying: ‘Madiba had been called to the office and [was] informed of this offer of Botha and then he was given, I think, a copy of Hansard … a page or two of Hansard where Botha had made this offer. We then discussed it, and it didn’t take long for us to unanimously reject the offer. We discussed it among the five of us and, of course, rejected it. And Madiba then, of course, drafted a reply, which we all agreed to. We all helped with the reply and then, of course, he drafted the speech that Zindzi read at a rally in Jabulani.’ If this account is correct, it is instructive to note that Mandela was not the only Rivonia trialist who, in the mid-1980s, started to make overtures to the Botha regime.2

In the meantime, numerous other ‘security prisoners’ quietly accepted Botha’s offer. They included the Rivonia trialist Denis Goldberg, who had been held in Pretoria Central for 22 years. Goldberg was released on 28 February 1985 and put on a plane to Israel where he was reunited with his family. He later worked for the ANC in London, and returned to South Africa in 2002. He was made to sign a document. He said later that he had grown tired of prison, and he knew in any case that negotiations had effectively begun.