Читать книгу Prisoner 913 - Riaan de Villiers - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

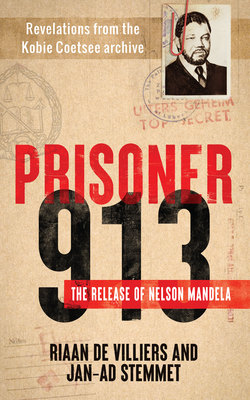

About this book

ОглавлениеRiaan de Villiers

THIS VOLUME is based on largely secret records about Nelson Mandela kept by Kobie Coetsee, Minister of Justice and Prisons, in the last phase of the apartheid regime. In this position, Coetsee presided over the last eight years of Mandela’s incarceration and his eventual release. The records effectively comprise Coetsee’s file on Mandela – ‘Prisoner 913’ – kept in his ministry.

Coetsee removed the archive – probably illegally – when he vacated his ministry shortly before the transition to democracy. He was about to hand it to the co-author of this volume, the historian Jan-Ad Stemmet, when he died suddenly in 2000. The extraordinary story of Jan-Ad’s brief interaction with Coetsee and the rediscovery of the archive some 13 years later is told in the next essay.

The fact that Coetsee kept a file on Mandela (and other ‘security prisoners’) is not remarkable in itself – given his portfolio and Mandela’s growing prominence, this would have been routine. However, the archive helps to reveal that Coetsee’s records far exceeded the bounds of any conventional administrative function.

As is widely known, from 1985 onwards Coetsee took a special interest in Mandela, and eventually started secret talks with him that presaged his eventual release. This interest, and the way it played itself out, is reflected in the archive’s extraordinary scope; the vast 913 file contains a wealth of material about every conceivable aspect of Mandela’s incarceration, ranging from secret government memorandums and other documents through medical reports, letters, press cuttings, and handwritten notes to a plethora of other material.

Rather sensationally, the archive also contains transcripts of clandestine recordings of many of Mandela’s conversations with a growing stream of visitors while in prison, ranging from foreign dignitaries and the Commonwealth Eminent Persons Group to government ministers, his lawyers, family members, fellow ‘security prisoners’, and other political role players.

As explained elsewhere, prison warders at that time routinely made notes of visits to certain categories of prisoners, notably ‘security prisoners’. However, the archive discloses that Coetsee introduced what amounted to a second-track intelligence operation, aimed at monitoring everything Mandela and some other prisoners said or did, and utilising this knowledge to inform his own agenda as well as government strategy.

Put differently, Coetsee used his position to become Mandela’s ‘gatekeeper’, jealously guarding access to his ‘star prisoner’, and placing himself in a position to control or influence the entire process surrounding Mandela’s incarceration and eventual release. As such, these transcripts provide a unique window on Mandela’s beliefs, motivations, strategic decisions, and the course of events at that time.

////

If the archive presents researchers with a unique resource, it also presents them with a formidable challenge. It comprises hundreds of files totalling some 13 000 pages, filed in a sprawling and untidy range of categories. Over the years, some items have become misplaced, resulting in some key documents turning up in unexpected places. Documents are typed, telexed, handwritten and photocopied, and some are very difficult to decipher.

The archive is equally vast in scope, reflecting a range of dimensions – administrative, legal, political, diplomatic, medical and personal – surrounding Mandela’s incarceration, moving through several stages from his ‘deep’ incarceration which still held in the early 1980s through renewed prominence sparked by growing international pressure and internal unrest, to his eventual ‘open imprisonment’ and release.

Notably, the Mandela file – simply labelled ‘913’ – is just one such composite file in the Coetsee archive. Similar, albeit less extensive, records were kept on other ‘security prisoners’, notably Walter Sisulu (Prisoner 916). (Also, while our narrative ends when Mandela walks out of prison on 11 February 1990, the secret surveillance of leading ANC figures continued for a significant period, and some of these records also appear in the archive.)

The entire archive – or, more accurately, the whole 913 file – tells a sweeping and multifaceted story, far too big to capture in a single volume. Given this, we decided to focus on a single theme, namely the light cast by the archive on the hidden process surrounding Mandela’s impending release in the last years of his imprisonment.

As noted by my co-author, the Coetsee archive is not complete enough to allow the development of a continuous and comprehensive narrative. Therefore, we have juxtaposed our selected material with standard accounts by two key role players, namely Mandela himself – in his autobiography Long Walk to Freedom (1994), and former President F.W. de Klerk, in The Last Trek: A New Beginning (1998), who released Mandela and set in motion the transition to democracy. Put differently, we use the disclosures in the archive to amplify their accounts, plugging the gaps where indicated. In line with these accounts, our narrative moves forward chronologically.

In the course of developing our narrative, we also found that Secret Revolution: Memoirs of a Spy Boss (2015) by Dr Niël Barnard, head of the National Intelligence Service (NIS) at that time, became directly relevant.

////

Against this background, the archive yields some notable new insights. Without wishing to pre-empt the detailed disclosures as they arrive at their proper time in the course of our story, it reveals:

That Mandela repeatedly offered to act as ‘facilitator’ between the NP government and the ANC, and that some of his proposals for a negotiated settlement cut across accepted ANC policy;

That Mandela, with the collaboration of Coetsee and the Department of Prisons, launched an extensive campaign, while installed in a cottage at Victor Verster Prison, to meet as many released prisoners and other political leaders as possible, with a view to moderating their political views and strategies;

That, from December 1989 onwards, again with the government’s knowledge and approval, Mandela began to talk to the ANC leadership in Lusaka, conveying various requests and proposals, including the terms of a proposed negotiated settlement;

That the ANC responded by moderating some of its public statements – notably its 8 January statement in January 1990 – at Mandela’s (and effectively the government’s) request, and potentially also some of the decisions taken at a key meeting between released ‘security prisoners’ and other internal leaders of the broad resistance movement and the ANC in exile in Lusaka in late January 1990; and

That talks between Mandela and the government about the terms of his release and a negotiated settlement continued up to De Klerk’s address on 2 February.

Lastly, it casts light on one of the most puzzling themes in the story of Mandela’s release, which perplexed various other role players – ranging from Margaret Thatcher to diplomats active in South Africa to the ANC’s leadership in exile – for some time, namely his apparent reluctance to leave prison. This was partly due, the archive discloses, to his strategic efforts to bargain for a ‘package he could take to Lusaka’. However, it also reveals that Mandela was greatly discomfited when De Klerk abruptly told him, on 9 February 1990, that he would be thrust back into the outside world two days later.

////

In the process, the archive reveals that both Mandela’s and De Klerk’s accounts of events are highly selective, to the point of being misleading. While, in Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela writes quite openly about his decision to start talking to the government, as well his interaction with Coetsee and other government role players, highly complex and contentious aspects of this process are dealt with in a deceptively simple way. Moreover, in a now glaring anomaly, he jumps straight from his meeting with De Klerk on 13 December 1989 to the latter’s famous address in parliament on 2 February 1990. The archive discloses that a great deal happened in between.

For his part, De Klerk writes – in typically rational and measured fashion – about being unaware of the second-track process involving Coetsee, being informed about it after becoming leader of the National Party prior to rising to the presidency, lending this process his tacit approval, and his first meeting with Mandela in December 1989. He goes on to record that they largely swopped generalities, and ‘concluded that they could do business with one another’.

However, the archive reveals that their meeting went far further – that they began to discuss the terms of Mandela’s release as well as the terms of the transition, and arranged that Mandela would start relaying some of these proposals to Lusaka. Moreover, an offer was made to Mandela that might have changed the course of South African political history, only to disappear mysteriously just before 2 February 1990.

////

Early readers of this manuscript have responded in positive and encouraging terms, but have also asked several probing questions. One issue they have raised is why we don’t make more of the series of meetings between the secret committee appointed under President P.W. Botha and including Dr Barnard, aimed at exploring – and moderating – Mandela’s political beliefs.

The answer is twofold. In his memoirs, Barnard writes extensively about these meetings which ranged from mid-1988 to some point in 1989.1 According to him, the committee comprised himself; S.S. (Fanie) van der Merwe, director-general of Justice; Mike Louw, deputy director general of NIS, and General Willie Willemse, Commissioner of Prisons, who had come to know Mandela in earlier years on Robben Island. (In Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela writes that the committee was headed by Kobie Coetsee, and included Willemse, Van der Merwe and Barnard.)2

Barnard states explicitly that the meetings were recorded by NIS, and seems to draw on what may well be a complete set of transcripts in the course of his discussion. However, the Coetsee archive contains only one such transcript, dated early in 1989, and only Barnard and Willemse were present. While the source is not stated, this transcript probably came from NIS, and seems to confirm that these meetings were not recorded by the Department of Prisons as well.

This single transcript paints an unflattering picture of Barnard’s interaction with Mandela. However, we eventually decided to omit it from our narrative, first because reflecting only one of this lengthy series of meetings might have painted a distorted picture of the discussions as a whole, and second, because, given its probable source, it might have caused legal difficulties.

Another issue raised by readers is why we have not included more material about Mandela’s interactions with Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, his children, and other members of his family.

The archive confirms that Madikizela-Mandela visited her husband in prison very regularly, sometimes under extremely difficult circumstances. In earlier years, besides his lawyers, she was effectively Mandela’s only link with the outside world. This role gradually faded as Mandela’s global stature grew, the terms of his imprisonment improved, his interaction with the government intensified, and he was allowed greater contact with a range of political role players. At the same time, the transcripts in this period attest to growing tensions between Mandela and Winnie, much of it centred on her conduct and those of his children. In the last phase, Mandela was reluctantly forced to come to terms with more serious allegations about Winnie’s conduct. However, he still seemed to gain comfort from her visits.

Among other things, Mandela was a patriarch, and the transcripts tell a moving story of his attempts to continue playing a role as husband and father from behind prison bars, and his anguish at his inability to protect his family against the ravages wrought by his absence as well as sustained brutalisation by the security police. This is a moving, often disconcerting, story which, for space and other reasons, we have left to other researchers to explore. Doing justice to this material will require a separate study. For ethical and other reasons, it would need to be approached with great care and circumspection.

A few of these conversations have been included, due to their direct relevance to our theme as well as their public interest. This includes some startling revelations in a conversation between Mandela and two family members about the background to his arrest. Even then, some names and a single sentence have been withheld.

A third issue is why we don’t draw more explicit conclusions about the revelations in the archive, notably what they imply about the central figure of Mandela, and formulate an overarching thesis.

The disclosures and their implications are complex and contentious. For that reason, we have concentrated on placing the material relevant to our theme in the public domain and drawing out some immediate implications, leaving readers to reach their more general conclusions themselves.

In the course of a particularly trenchant report, one early reader asked what our study really said about Mandela, suggesting a formulation of his own, namely that, while in prison, Mandela had trodden a ‘fine line between compromise and capitulation’.

While acknowledging the elegance of this formulation, we would hesitate to draw such a generalised conclusion. During his incarceration, Mandela was faced with a formidable array of challenges, under overwhelmingly difficult circumstances, and over a very long period. The archive reveals how – and then, only over the last part his 27 years in prison – he sought to deal with these pressures – from the government, the ANC in exile, his fellow prisoners, the growing internal resistance movements, as well as his family – while struggling to keep abreast of political events in South Africa as well as internationally. It’s a monumental story.

In this setting, readers may be surprised, and perhaps even taken aback, by some of the disclosures involving Mandela. However, for us – having lived with the archive, including aspects which remain undisclosed, for several years – he has grown rather than diminished in stature, and become more human in the process. It also makes his eventual ascent to the leadership of the ANC and the South African presidency all the more remarkable. Perhaps, then, the archive is also valuable because it reminds us – as Mandela himself was wont to remark in later years – that he was no saint, but a (flawed and fallible) human being.