Читать книгу Prisoner 913 - Riaan de Villiers - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

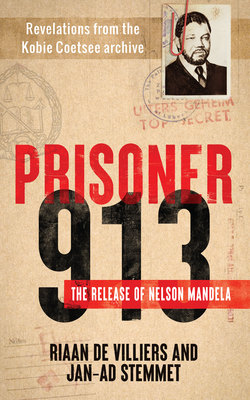

My journey with the Coetsee archive

ОглавлениеJan-Ad Stemmet

IN 2013, I received a call from Huibré Lombard, head of the Archive for Contemporary Affairs (ARCA) at the University of the Free State. ARCA staff were busy cataloguing a new collection, and she thought I might be interested.

ARCA is a gem. It began life in 1970 as the Institute for Contemporary History, or Instituut vir Eietydse Geskiedenis. Its formal mission was to collect and preserve documents that would record South African political history after 1902. It initially consisted of three divisions, namely a documentation division, a press cutting division and a research division. In 1998 the documentation division became the Archive for Contemporary Affairs. More informally, ARCA was (and remains) the archive of choice for National Party politicians and other role players in Afrikaner public life. As such, it’s a political and historical treasure trove.

It’s also a black box – partly housed underground, it’s an immense catacomb of interleading fireproof chambers, locked vaults, and safes-within-safes. Some material is subject to moratoriums, some proscribed by law and some imposed by donors themselves. The route from my office to ARCA’s front end is a short walk across the campus, one I had taken many times previously, but which after the phone call I now took with a renewed sense of excitement.

Huibré had placed a single grey archival box on top of a desk in the main reading room – a tranquil space where historians and other researchers are surrounded by books, antiques, and busts of apartheid-era heads of state and government. Inside, I found a delectable wad of yellowing documents, all stamped ‘UITERS GEHEIM / TOP SECRET’. The apartheid-era government stamp still retained its forbidding magenta colour. I looked more closely at a single document, and read: ‘Transkripsie van gesprek tussen 913 en Winnie Mandela …’ (transcription of conversation between 913 and Winnie Mandela). For a moment, the room around me faded. I realised a wheel had turned full circle, and I was looking at material from the secret archive of apartheid minister Kobie Coetsee.

////

IN JULY 2000, as wide-eyed young historian, I conducted a series of interviews with government role players in the South African transition. I also decided to interview Kobie Coetsee, Minister of Justice and Correctional Services from the early 1980s to the early 1990s, who was known to have played a central (if shadowy) role in the process surrounding Mandela’s release. People who knew him said he had become disillusioned, and would probably not agree to an interview.

I contacted him in July 2000. Speaking on the phone, he was brusque, and reluctant to see me. But he eventually agreed, and we met at his home in Bloemfontein on Thursday, 27 July 2000. While cordial, he was initially reserved. But when he began to talk about the 1980s, he became animated, and eventually quite agitated. He seemed to feel his contribution to the process resulting in Mandela’s release had not been adequately recognised. I sat in silence, listening to a steadily mounting monologue.

Coetsee told me he had previously intended to write his memoirs, but had given up on the idea. To my amazement, he jumped up and insisted that I redirect my research to focus exclusively on his professional life. This, he assured me, could be published and become a bestseller. If I undertook to do this, he would make me the heir to his knowledge and his entire private archive.

‘I will give you all of it,’ he said, and added: ‘What I will give you are bombs, bloody bombs, my friend. And when I say bombs, you’d better believe it. I mean, atom bombs. We – you and I – will blow everything open. Everything!’ We agreed that I would return the next week so that we could discuss a plan of action, and he left for his farm outside Bloemfontein.

Two days later, on Saturday, 29 July, I switched on the television to watch the evening newscast. In a lead item, the SABC reported that Coetsee had died earlier that day of a heart attack. Shocked and dismayed, I thought I would never learn what Coetsee had been so agitated about, and would never gain insight into his archive. I continued my research, and was privileged to gain access to some of South Africa’s most important political mandarins, power brokers, and other political heavyweights. Coetsee featured mainly in negative brushstrokes and sharply critical anecdotes. Years passed, and despite the fact that I drove past his home on my way to the university every working day, my encounter with Coetsee gradually passed to the back of my mind.

////

AT ARCA, this process was put in rapid reverse. As I pulled out more documents from vaguely labelled boxes, it began to dawn on me that, 14 years after my encounter with Kobie Coetsee, I had finally come face to face with his archive. While I was unaware of this, it had been donated to ARCA by his widow, Ena, several years previously. She had also passed away since. I also soon realised that, despite Coetsee’s second-tier status, this was one of the greatest single discoveries in recent South African political history.

A large part of the archive comprised a series of files simply named ‘913’. Many were stamped ‘SECRET’ or ‘TOP SECRET’. I soon established that ‘913’ was the permanent number assigned to Nelson Mandela by the Department of Correctional Services, over which, in addition to the Justice portfolio, Coetsee had presided from 1980 to 1994. This was used to tag the extended file on Mandela that Coetsee kept in his ministry, which had grown to huge proportions over the years. Spanning more than a decade, the file dealt with almost every aspect of the elaborate government process that had developed around Mandela’s incarceration, up to his release in February 1990 and beyond. Whether legally or illegally, Coetsee must have removed these documents together with the rest of his archive when he vacated his ministry in the Union Buildings just before the first inclusive elections in 1994.

I was awed by the sheer size of the 913 file, which took many months to assimilate. It comprised thousands of documents, collected in various folders, and including government reports, memorandums, letters, informal notes, press cuttings, and other documents. Perhaps most startlingly, it also contained transcripts of hundreds of meetings between Mandela and his visitors in prison, ranging from Winnie Mandela, his children and other members of his family, and his legal advisers and fellow ‘security prisoners’, to domestic and foreign journalists, politicians, government officials and other role players in the lead-up to the transition.

Some of these transcripts were handwritten by prison officials who, as prescribed by prison regulations, had sat in on these visits. However, it also became clear that many had been transcribed from clandestine recordings which had formed part of a massive covert surveillance programme instituted in the early 1980s as Mandela gained growing political importance. The transcripts were minutely scrutinised and analysed, in order to extract every possible ounce of intelligence and strategic advantage. Covering letters and scribbled annotations revealed that some of these transcripts had, upon request, landed on the desks of Coetsee and other selected government role players within a day.

Added to these were a raft of reports, thick and thin, summarising and analysing every possible aspect of 913’s existence – his medical condition, his psychological make-up, his emotional well-being, his view of whites, blacks and the South African situation, the ANC in exile, the mass political and labour movements – as well as lengthy analyses of what would happen if he died in prison, or were to be released under various conditions. The gradual development of the global ‘Release Mandela’ movement was chronicled in startling detail, down to the very last municipality issuing a statement or renaming a street in far-flung corners of the world.

The person at the centre of this process – amounting to a full-blown, second-track intelligence operation – was Kobie Coetsee. The first recordings appear in 1984, four years into his term, and the archive reveals how he actively used his dual portfolios and his privileged stream of information to become the gatekeeper to the world’s most famous prisoner. While other ‘security prisoners’ were also monitored, it is clear that Coetsee developed an almost obsessive preoccupation with Mandela, resulting in a staggering amount of information. For about a decade, he knew more about Mandela than anyone else, and used this knowledge to control and manipulate the complex situation surrounding Mandela to his and the government’s perceived advantage.

All this presented me with a massively exciting opportunity – but also a massive challenge. As a result, in the same year, I invited Professor Willie Esterhuyse of the University of Stellenbosch to join me in studying the archive, and we spent months sifting through the material. Our paths eventually diverged, and Professor Esterhuyse went on to write about Mandela’s and Coetsee’s ‘leading-edge diplomacy’ in a book published in 2015.1

In 2017, my friend, the former journalist and specialist editor Riaan de Villiers, joined me as co-author. A visit to Bloemfontein, many emails and many hours of phone conversations followed. Initially, we tried to develop an account of all the themes and the entire period covered by the archive, but remained overwhelmed by its vast scope. Moreover, as our understanding of the material deepened, we began to realise that the archive contained some startling revelations about the latter stages of the process surrounding Mandela’s release, and we decided to concentrate on this single theme. Excitedly, we began to reread certain documents and transcriptions, and share some new insights. From then on, the book began to take shape quite rapidly.

////

Two overarching points need to be made. The first concerns the vast scope of the archive, not only in terms of volume but also its multiple dimensions. Almost a decade’s worth of secret memorandums and other government documents provides a unique window on the hidden workings of the NP government, as well as the actions of key role players. At that time, insight into this material would have been truly lethal knowledge. Added to this, summaries and transcripts of Mandela’s conversations with literally hundreds of visitors illuminate not only his interaction with Coetsee and other government figures, but also his relationships with his captors; his fellow prisoners; his legal representatives; and Winnie Mandela and other members of his family. Some of these revelations are not only political, but also social, as well as intensely personal. Beyond our chosen theme, much of this remains unexplored.

The second, related, point concerns the scope of this book. Perhaps it will be best to say what it doesn’t do, before saying what it does. Firstly, it does not seek to retell the story of the South African transition, based on revelations in the archive. The transition was a hugely complex process, with many more dimensions, both local and global, than those touched on in this book. All of these worked in concert to end white domination and propel South Africa into a largely peaceful transition to an inclusive constitutional democracy. It has been and would remain a mistake to try to reduce the transition to a single causal driver.

Secondly, this book does not even seek to retell the story of this single strand, namely the largely secret process surrounding Mandela and his interaction with various government and other role players during the last few years of his incarceration. Among other things, the Coetsee archive is not complete or continuous enough to allow for the development of an entire alternative narrative. However, what it does do is to cast new – and sometimes startling – light on aspects of this process, which, we believe, requires the accepted history to be partly revised and rewritten.

Throughout, we have tried, as far as possible, to let the material speak for itself. In some instances, beyond providing essential background and context, we have tentatively drawn out some of the implications; in others, we have left this to the reader.

To conclude, the Coetsee archive forms part of our national heritage. As such, it is bigger than any single researcher or author, and no one should seek to claim any exclusive insight into or ownership of its contents, much of which is extremely sensitive. We tried to deal with the material pertinent to our theme as responsibly as possible, steering clear of conspiracy theory as well as political pulp fiction. We hope other researchers will do so too.