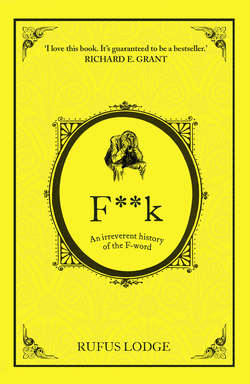

Читать книгу F**k: An Irreverent History of the F-Word - Rufus Lodge - Страница 10

Grose Vulgarity

ОглавлениеOf all the lexicographers, etymologists, encyclopedics, and anoraks who have devoted their lives to chronicling the English language at its most blunt and disorderly, the award for displaying the most conspicuous courage in dictionary corner must go to Francis Grose. Aptly named, you might think, and the surviving engraving of his friendly form does suggest that he was the answer to the oft-voiced question, ‘Who ate all the pies?’. But Grose deserves every credit for his lifelong quest to bring recherché knowledge into the public eye. He penned comprehensive (for the late eighteenth century) volumes devoted to sites where antiquities might be found; to the history of armour and weaponry; and to local proverbs gathered from every nook and cranny of the British Isles.

His enduring monument, though, was his Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, first published in 1785 and reprinted many times thereafter – although as the boundaries of good taste narrowed during the nineteenth century, later editions tended to remove some of Grose’s more daring entries.

From the start, he was prepared for outrage from the disgusted citizens of the newly fashionable resort of Tunbridge Wells. ‘To prevent any charge of immorality being brought against this work,’ he declared in his introduction, ‘the Editor begs leave to observe that when an indelicate or immodest word has obtruded itself for explanation, he has endeavoured to get rid of it in the most decent manner possible; and none have been admitted but such, as could not be left out, without rendering the work incomplete.’ Couldn’t have said it better myself.

Daring though Grose was in the collecting of his vulgar language, there were some words that still had to be hidden beneath a veil of modesty. Most extreme was ****, which could not even be included in the alphabetical dictionary without revealing its identity. But Grose did offer some clues: a ‘nincompoop’, he declared, was ‘one who never saw his wife’s ****’; while a gentleman who entered a woman without sparing any of his vital fluids could be said to have ‘made a coffee house out of a woman’s ****’. Not that Grose was exactly short of synonyms for a woman’s mysterious ****. Among them were her ‘bite’, ‘bumbo’ (as used, apparently, by ‘Negroes’), ‘Carvel’s ring’, ‘cauliflower’, ‘cock alley’, ‘cock lane’, ‘commodity’, ‘dumb glutton’, ‘gigg’, ‘madge’ (has Madonna been told?), ‘mantrap’, ‘money’ (rather alarmingly, this was used only of young girls), ‘muff’ (oops, nearly given the game away), and ‘notch’.

On special occasions, the woman’s **** could be joined with the man’s ****, or, in other words, his ‘prick’, ‘tarse’, or ‘plug tail’, kept fuelled by his ‘bawbels’, ‘gingambobs’, ‘nutmegs’, ‘tallywags’, ‘tarrywags’, and ‘whirlygigs’ (don’t try that one at home). The act of union could be described (yes, even in 1785) as ‘making the beast with two backs’, ‘making a buttock ball’, doing a ‘clickit’ (as foxes do, noisily, at night), ‘docking’ (think space capsules), ‘humping’ (going out of fashion by the 1780s, we learn), ‘joining giblets’ (very romantic they were, in the late eighteenth century), ‘creating a goats-gigg’, ‘strumming’ or ‘knocking’ (a man did this to a woman), ‘mowing’ (but only in Scotland; in England, you better keep off the grass), ‘screwing’, ‘wapping’ (now we know why Rupert Murdoch based his newspapers there), or, most common of all in the years preceding 1800, ‘swiving’. In order to prevent an unwanted outcome, a man might choose to ‘fight in armour’ by wearing a ‘c-d-m’ (that’s a ‘cundum’ to you and me, sir).

Some gentlemen preferred not to bother with the ladies at all, and might fairly be described as a ‘back gammon player’, an ‘indorser’, ‘a madge cull’ (doing away with a ‘madge’, presumably), a ‘shitten prick’ (slightly too graphic, that one), or as frequenting the ‘windward passage’ (much more poetic).

If more solitary pleasure was intended, a man (but obviously never a woman) might ‘frig’ (‘to be guilty of the crime of self-pollution’), ‘get cockroaches’ (maybe I’m doing it wrong), ‘box the Jesuit’ (likewise), or ‘mount a corporal and four’ (the corporal is the thumb, and you can work out the rest for yourselves). Once he’d tired of playing by himself, the man could entice the lower class of woman to perform ‘bagpipes’ upon him (‘a lascivious practice too indecent for explanation’), give him a good ‘huffle’ (‘a piece of beastiality too filthy for explanation’, but strangely similar to that bagpipes manoeuvre), or even indulge him in a quick spasm of ‘larking’ (‘a lascivious practice that will not bear explanation’, even here, where I can only refer you to a modern dictionary and the word ‘irrumation’).

Many of Grose’s definitions shine a surreal light upon the habits and prejudices of 1785, not least the three-and-a-half pages he devoted (in a dictionary!) to a diatribe against gypsies. He was greatly interested in the word ‘dildo’, defined thus: ‘an implement resembling the virile member, for which it is said to be substituted, by nuns, boarding school misses, and others obliged to celibacy, or fearful of pregnancy’. These unusual objects ‘are to be had at many of our toy shops and nick nackatories’, though I wouldn’t advise you to enquire at Toys R Us.

It’s intriguing, to say the least, to discover that the eighteenth-century gentleman needed a phrase to describe ‘a lighted candle stuck into the private parts of a woman’, which was known as a ‘burning shame’. Maybe the candle was an attempt to burn the disease out of a ‘fireship’ (a woman with a STI), who was suffering perhaps from ‘French Disease’ (damn those dirty frogs) or ‘Drury Lane Ague’ (known today as luvvie’s syndrome). Of course, all that unpleasantness could be avoided by a ‘flogging cully’: ‘one who hires girls to flog him on the posterior, in order to procure an erection’ (the life of an architect was clearly not a happy one).

But you haven’t come to the pages of this book for such trivia, I hear you say. So we move, at last, to the pages of the dictionary devoted to words beginning with the letter ‘F’, of which precisely two had to be abridged in the interests of public decency: ‘f—k’ (meaning ‘to copulate’, you will be startled to discover); and ‘f—k beggar’, which is of course a synonym for ‘buss beggar’; you know, ‘an old superannuated fumbler’, fumbling in this instance suggesting that the architect’s erection might be less sturdy than he was hoping. There was one further reference to our favourite word, in the appearance of ‘duck f-ck-r’, which Grose helpfully defined as ‘the man who has the care of the poultry on board a ship of war’ (no bestiality in the Navy, maties).

Of course, as keen lexicographers, you will be much more interested to know that, in Grose’s alphabet, words beginning with ‘I’ and ‘J’ intermingled in a saucy manner, as if the two letters were interchangeable; and that ‘V’ came before ‘U’ (whereas a gentleman always makes sure that ‘U’ should come first).