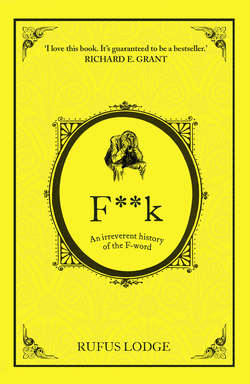

Читать книгу F**k: An Irreverent History of the F-Word - Rufus Lodge - Страница 9

Poetry in Flyte

ОглавлениеIt was, perhaps, the Renaissance equivalent of battle rap: two skilled artisans in the arts of insult and verse, flinging lines back and forth for the entertainment of a rabid crowd. This was not a beer-soaked hip-hop club on Detroit’s 8 Mile Road, however, but a rowdy evening at the court of King James IV of Scotland, circa 1500. The monarch would assemble his courtiers, and let loose two of his sharpest wordsmiths to heap invective and obscenity on each other’s head.

The result was a jolly good flyting, a word that promised scolding and wrangling with the overtones of violence. As the audience was hand-picked by the King, there were no holds barred – with the result that the strenuous Flyting of Dumbar and Kennedie has passed into history as the earliest known printed text to include one of the rudest words in the Scottish (and English) language.

The two participants were William Dunbar and his slightly older but less celebrated opponent, Walter Kennedy. Dunbar was the man who would go down in literary history, the Ali to Kennedy’s Frazier; but it was the lesser-ranked fighter who was credited in the 1507 anthology of Dunbar’s verse with calling his antagonist a ‘fantastic fule’ and ‘ignorant elf’ to warm himself up, before delivering his killer lines: ‘Skaddit shaitbird and common shamelar/Wanfukkit funling that Natour maid ane yrle’. Which translates, roughly, as ‘Mangy rascal and common scrounger/Misbegotten [wanfukkit, or produced by an unhappy act of intercourse] foundling that Nature made a midget’.

Dunbar wasn’t a man to let that kind of thing stand unanswered, of course, and he quickly replied with some delicious lines alleging that Kennedy was both ‘cuntbitten’ and ‘beschitten’. Ah, the magic of poetry …

What isn’t clear is how these insults were recorded for posterity, the court of James IV being intolerably ill-supplied with cassette recorders or iPhones. Did the King’s retinue include the speediest scribe in the land? Did both men actually arrive with their anger pre-cooked, and merely pass over their manuscripts to an editor at the end? Or did Dunbar, in fact, cook up the whole stew himself, thereby entitling himself to sole credit for the results? History does not tell us. Nor, after the sixteenth century, did collections of verse dare to reproduce the most extreme of the two poets’ slingshots in full: ‘wanfukkit’ was quietly censored to read ‘wanthriven’; ‘cuntbitten’ revised as ‘flaebittin’, suggesting that those midges were every bit as annoying four hundred years ago as they are today.