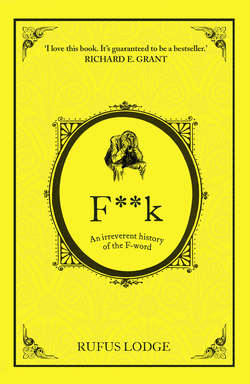

Читать книгу F**k: An Irreverent History of the F-Word - Rufus Lodge - Страница 8

Some Word There Was, Blacker Than Tybalt’s Death …

Оглавление‘A word,’ Shakespeare’s characters are wont to say, as they beg a moment of their companion’s time. But surely one word was forbidden even to this most vocabulary-rich of writers? Could the Immortal Bard really have resorted to the basest of language to please the filthy ears of the theatre-goers at the pit of the Globe?

Several early editions of his work suggest that he could, and did. Not the F-word, as such, but a six-letter term for someone in the very act of fornication – and not with a timeless heroine, a Cleopatra or a Juliet, but with a more humble member of God’s kingdom: the common British rabbit.

The offending text, if offence it should cause, could be found in Henry IV Part 1, Act II, Scene iv, in the voice of the one Shakespearian character whom it is possible to imagine effing and blinding in the wings: that buffoonish gourmet and glutton, Falstaff. At which point I refer you to the 1778 edition of Shakespeare’s collected plays: in which Falstaff appears to dare his king to ‘hang me up by the heels for a rabbet-fucker, or a poulter’s hare’. The editor has inserted a helpful footnote from no less an authority than lexicographer extraordinaire, Dr Samuel Johnson: ‘“Rabbet-fucker” is, I suppofe, a fucking rabbet.’ (By the same logic, Dr Johnson would doubtless have explained that a ‘motherfucker’ was actually a fornicating matriarch.)

But, as Hamlet says to Laertes, ‘I have done you wrong’, sweet Bard. The clue is in that mysterious ‘suppofe’: there, as in the offending rabbit reference, a sinless ‘s’ has been printed as a fallacious ‘f’, translating a sucking rabbit (or someone who makes a habit of sucking these innocent furry creatures) into a fornicating example of the same mammal. A veritable comedy of errors, my lord.

How, you might ask, did the Bard convey the sense of the F-word without descending to such common tongue? By referring to an ‘act’, on occasion, as an abbreviation (though not too abbreviated, one hopes, for Juliet’s sake) of the enactment of copulation. On two occasions, however, Shakespeare was cunning enough a linguist to suggest the forbidden term whilst still being able to swear innocent intent.

The first returns us, inevitably, to the company of Falstaff, in the same play in which he debates the rearing habits of the rabbit. Near the climax of the drama, he is engaged in heated conversation with the aptly named Pistol, a hothead who is much given to letting rip with his own command of invective. Where his twenty-first-century equivalent might cry, ‘I don’t give a fuck about …’, Pistol opts for the safety of a foreign language, in this instance French, while still giving his monolingual audience enough of the F-sound to make his meaning entirely clear. So let’s hear him in action: ‘A foutra for the world and worldlings base!’ And, a few lines further: ‘A foutra for thine office’. Pistol certainly can’t be accused of going off half-cock. (For an entire scene devoted to the build-up to a ‘foutra’ joke, meanwhile, try Henry V, III. iv.)

Sir John Falstaff was also in the cast of Shakespeare’s second foray into F-word euphemism, in The Merry Wives of Windsor, IV.i. But for once he is out of the room when Sir Hugh Page, a Welsh parson of less learning than he assumes, gives the leading characters a break by quizzing young William Page about his knowledge of Latin grammar. Having led him through the pitfall-free ground of the nominative and accusative cases, he asks the boy to provide him with the ‘focative’. Good scholar that he is, William corrects him: ‘O, vocativo’. But Sir Hugh ploughs on with his ‘foc’-word, setting up Mistress Quickly for a particularly limp pun about a carrot. By the time that Sir Hugh moves on to the genitive case, the coarser element of the Elizabethan audience would doubtless have been in hysterics – repeating ‘He said “focative”!’ and ‘Ha, ha! “Genitive”!’ to each other like schoolboys who’d just learned Monty Python’s parrot sketch. Fortunately, as keen viewers of BBC3 will tell you, modern comedy is much more sophisticated.