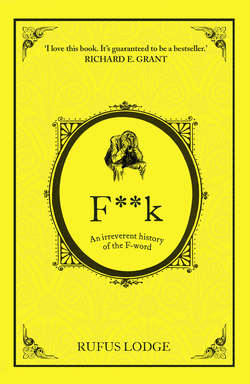

Читать книгу F**k: An Irreverent History of the F-Word - Rufus Lodge - Страница 5

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Surveys of the British population claim that the nation’s favourite words are ‘serendipity’, ‘nincompoop’, and – isn’t this sweet? – ‘love’. But there is another kind of love in this country, which dares not speak its name; and that’s the love for another word with just four letters, but an entirely different meaning. It’s been with us since the Middle Ages, it’s as British as curry and chips, it rolls off the tongue of the average English-speaker with impressive frequency and ease, and it is surely, in our heart of hearts, the Great British Public’s eternal favourite: the expletive known, and treasured, as the F-word.

It’s a word from which I was shielded during my sheltered upbringing in an English country village – only to be shocked into brutal awareness when I moved to a large town. Through my early teens, it was still a word used only by other people. But by the time I was ready to leave school, greet the world, and hit the big city, I was as fluent as any docker or sailor in the land. Since then, the trusty F-word has been my companion in times of jubilation or despair, comfort or stress, endlessly adaptable, permanently relevant, and emotionally supportive in the way that only the truest of friends can be.

As you will see from the pages of this book, the F-word is also the most powerful word in our language, capable of arousing outrage and panic among the greatest in the land. So potent is its force, in fact, that when it explodes unexpectedly, it’s known as the F-bomb, the mortal enemy of live TV and radio presenters around the world. It has inspired poetry and pornography, political protest and potty-mouthed pandemonium, and lots of things that don’t begin with the letter ‘p’. Take your seats, please, for a panoramic 500-year journey through the origins, adventures, and sexual liaisons of Britain’s favourite word. You’ll marvel at its versatility; thrill to its battles with the censors; revel in its unexpected appearances in the most embarrassing places; and, I hope, come away with a richer understanding of what makes that four-letter explosive so appealing, and so all-pervasive. You’ll also learn some new swear-words. And abbreviations. WTF else do you people want?

Why the F**k Do We Swear?

Scientists – yes, real ones, with ‘professor’ and ‘doctor’ in front of their names – agree that swearing is good for you. Or, at least, it’s good for you when you’re stressed, under physical attack or have someone with ‘professor’ or ‘doctor’ in front of their names telling you to put your hands into icy water and keep them there.

That was the experiment run at Keele University, where Dr Richard Stephens discovered that people who shouted swear-words, notably the F-word, could keep their hands in the killingly cold water for 40 seconds longer than those who were only allowed to say ‘My fingers have just fallen off’. The most effective thing to shout, almost certainly, was: ‘Fuck, that’s cold!’, though ‘Fucking scientists!’ came in a close second.

Over to Dr Stephens for the conclusions inspired by this legalised torture: ‘Used in moderation, swearing can be an effective and readily available short-term pain reliever if, for example, you are in a situation where there is no access to medical care or painkillers. However, if you’re used to swearing all the time, our research suggests you won’t get the same effect.’ Which is bad news for Gordon Ramsay.

Why is this so? ‘Swearing seems to activate deeper parts of the brain more associated with emotions,’ according to Dr Stephens. These areas are different from those that control the normal production of language. As a result, it has been possible for people to suffer a catastrophic brain injury, which has left them unable to carry out a conversation, without impairing their ability to eff and blind like the proverbial supertrooper. (Research is still continuing into what happens in the brain to cause outbursts of uncontrollable swearing among a minority of sufferers from Tourette’s syndrome.)

It’s time for another scientist: Professor Yehuda Baruch of the University of East Anglia, who declared in 2007 that swearing can ‘reflect solidarity and enhance group cohesiveness’. In other words, if one person in a group swears, and others feel some kind of bond with him, then they are likely to swear too. Not that this will be a surprise to anyone who’s ever stood in the crowd at a football match.

One last scientific fact: by accessing an area of the brain left untouched by more delicate language, swearing provides a form of catharsis, bypassing the usual restraints of polite conversation. So swearing relieves stress, and helps to ease the experience of pain. But why do English-speakers, who have an array of foul language at their disposal, almost universally agree that the most satisfying and cathartic form of swearing has to involve the F-word and its various derivatives?

Here we must leave human biology and head into the realms of psychology. What does the word ‘fuck’ convey? Sex, simply enough; and, beyond that, a degree of violence. ‘Fuck’ is a much more aggressive term than ‘have sex’ or ‘make love’: it can be consensual (between two saucy so-and-so’s who say to each other, ‘Let’s fuck’) but it can also be directly the opposite (‘I’m going to fuck you up’). It breaks two of society’s strongest taboos, and multiplies the impact of both misdemeanours by combining them.

Taboos don’t exist in isolation: they need a group of people to decide that something is beyond the pale, and then respect that decision. The English-speaking world has chosen to accept the F-word as one of the most offensive terms in its language. As expletives, ‘flip’ and ‘fuck’ perform exactly the same function, but only one of them is like to raise your maiden aunt’s eyebrows. The boundaries of taboo can change: for centuries, any reference to God’s wounds (those suffered by Jesus on the cross, in other words) enjoyed terrifying cultural power. Now ‘zounds’ survives only as an exclamation in comedy sketches about the Three Musketeers. But for more than 600 years ‘fuck’ has remained outside the realms of common decency – and only in the last fifty years has it slowly crept into the mainstream of our culture, to the point where some (but by no means all) newspapers and magazines will dare to print the four forbidden letters in full.

‘Fuck’ is also one of the most adaptable and multi-purpose words in the English dictionary, giving it a universal power that is denied to the C-word or the increasingly verboten N-word. It’s also, strangely, an equal-opportunity four-letter word. No races, genders, or minorities are singled out by its use: it divides the world easily into two groups, those who say ‘fuck’ and those who find it shocking. Some people step backwards and forwards between those two categories – the men who swear in the office or in the pub, for instance, but hate to hear the F-word being used ‘in front of the ladies’; or the parents who damn each other to hell, but drag their children away from the telly when Gordon Ramsay’s producer is shouting down his earpiece that he hasn’t said ‘fuck’ enough times yet.

‘Fuck’ is, when you get down to it, just a word like any other. But, at the same time, it’s different from every other word you know. Pour boiling water over your fingers, and you’ll soon remember why.