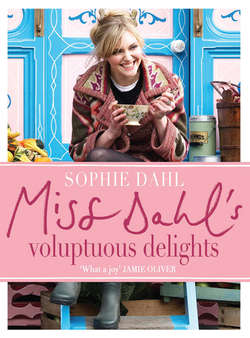

Читать книгу Miss Dahl’s Voluptuous Delights - Sophie Dahl - Страница 7

Introduction

ОглавлениеThe second word I ever spoke was ‘crunch’—muddled baby speak for fudge, which should have alerted my parents to what lay ahead. As a small child, food occupied both my waking and nocturnal thoughts; I had clammy nightmares about dreadful men made from school mashed potato wearing striped tights, chasing me into dense forests.

A welcome dream was a cloud made of trifle, a slick spring bubbling with chocolate or a fountain bursting with forbidden Sprite or Cherry Coke. My dolls had the fanciest tea parties in London and I kept a tight guest list, so the only person actually benefiting from the tea was me. My first (and last) rabbit was named for my then favourite breakfast food, the pancake. Pancake was a brute, and he performed an unnatural sex act upon his hutchmate, Maple Syrup, who was a docile, blinking guinea-pig. The shock killed Maple Syrup immediately and Pancake was banished to the country to live out the rest of his days in shame and isolation. It seemed unfair that his strange peccadilloes were rewarded with buxom country rabbits and fresh grass, but the karma police intervened and he met a gruesome end in the jaws of a withered fox.

I have always had a passionate relationship with food; passionate in that I loved it blindly or saw it as its own entity, rife with problems. Back in the day, in my esteem, food was either a faithful friend or a sin, rarely anything in between. Eating as sin is a concept more pertinent than ever before in this tricky, unforgiving today. I realized at an early age that I was born in the wrong time, food-wise. I would have been infinitely more suited to the court of Henry VIII, where the burgeoning interest I showed in food would have been encouraged and celebrated. Alas, in my London of the eighties it was simply cause for family mirth, sullen trips to the nutritionist and brown rice diets. Oddly enough, I was reasonably skinny with a great round moon face; just perpetually hungry like a baby bird. I got rather chubby and unfortunate-looking when I was about seven, and there are some rather sinister pictures of me looking like a grumpy old woman (I had a penchant for coral lipstick and any church-type hat), always with a large sandwich hanging out of my mouth.

I grew up surrounded by food lovers; my parents Tessa and Julian were natural cooks and both sets of grandparents were known for a full table. My earliest memories of food involve my paternal grandmother Gee-Gee, (an ex chorus-girl dancer, five foot of endless leg, saucer-blue eyes and marcelled blonde waves) who lived on the Sussex coast in a house surrounded by whispering trees. My dad and I would drive down from London, a journey that felt decades long to a child, but the monotony was forgotten as soon as Gee-Gee swung open the front door and we were embraced; first by a pleasurable blast of something roasting, and then by her. These lunches usually incorporated roasted something with gravy, Yorkshire pudding, roast potatoes, parsnips, cauliflower cheese, and definitely puddings: treacle tart with a cool lick of cream to sophisticate and sharpen the sugar, incredible crumbles, swimming in thick vanilla custard. Every day there was proper tea at Gee-Gee’s, with homemade scones, ginger cake and her best bone-thin china. She understood absolutely everything about life, except three things:

1 Why anyone, most specifically me, would become a vegetarian.

2 Why it was difficult for hunger to be limited to three times a day, with a little pang left over for tea, devoid of desire to pick between meals.

3 The attraction of violently-coloured eye shadow to a sixteen-year-old. (‘Like an ancient barmaid,’ she’d sniff at my peacock-feather-green eyelids.)

Gee-Gee was brilliant; she taught me to bake without fuss. I watched the quiet joy she derived from feeding those she loved and I took it with me like a tattoo into adulthood, making idle breakfasts and Sunday lunches, Indian summer dinners and rainy day teas, revelling in the simple pleasure cooking for people I cared about brought me.

If anything, this book is a total homage to my family and the appetite and culinary legacy they left me with: Gee-Gee; my maternal grandmother Patricia of Knoxville, Tennessee, with her fondness for grits, collard greens, and lemon chiffon pie; my Norwegian grandfather, Roald, and his vast appreciation for chocolate, borscht and burgundy; his second wife, Felicity, who in his absence continues to keep his table with the same spirit and standard; my aunts and uncle, fine cooks all; my mum and dad, my brothers and sister; each and every one of them has an influence in here somewhere.

I am not an authority on anything much, but I do feel qualified to talk about eating. I’ve done a lot of it. In my time I have been both round as a Rubens and a little slip-shadow of a creature. Weight, and the ‘how to’ maintenance of it, seems to be something that preoccupies a lot of people, and because I lost some, rather publicly, it is something people feel free to ask me about. I have had conversations about weight with strangers in supermarkets, on aeroplanes and in bathroom queues. I could talk until the cows come home about food and recipes and bodies and why as people we are so consumed by the three. I have sat next to erudite academic types at dinner, steeling myself for a conversation that will doubtless include something I know nothing about, like physics, only to be asked in a surreptitious tone, ‘How did you get thinner?’ At which stage I will laugh and say, ‘Well, it all started like this…’