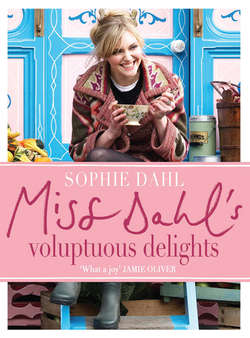

Читать книгу Miss Dahl’s Voluptuous Delights - Sophie Dahl - Страница 8

Autumn

ОглавлениеWe begin in the autumn because that’s when everything changed. Autumn is a season I love more than any other; for its smoky sense of purpose and half-lit mornings, its bonfires, baked potatoes, nostalgia, chestnuts and Catherine wheels.

It was late September. I was eighteen. I had experienced a rather unceremonious exit from school. I had no real idea about what I wanted to do, just some vague fantasies involving writing, a palazzo, an adoring Italian, daily love letters and me in a Sophia Loren sort of dress, weaving through a Roman market holding a basket of ripe scented figs. I had just tried to explain this to my mother over lunch at a restaurant on Elizabeth Street in London. She was not, curiously, sharing my enthusiasm.

‘Enough,’ she said. ‘No more alleged history of art courses. You’re going to secretarial college to learn something useful, like typing.’

‘But I need to learn about culture!’ She gave me a very beady look.

‘That’s it,’ she said. ‘No more. End of conversation.’

‘But I…’ The look blackened. I resorted to the historic old faithful between teenagers and their mothers.

‘God…Why don’t you understand? None of you understand me!’

I ran out into the still, grey street, sobbing. I threw myself on a doorstep and lit a bitter cigarette. And then something between serendipity and Alice in Wonderland magic happened.

A black taxi chugged to a halt by the doorstep on which I sat. Out of it fell a creature that surpassed my Italian imaginings. She wore a ship on her head, a miniature galleon with proud sails that billowed in the wind. Her white bosom swelled out of an implausibly tiny corset and she navigated the street in neat steps, teetering on the brink of five-inch heels.

Her arms were full to bursting with hat boxes and carrier bags and she was alternately swearing, tipping the taxi driver and honking a great big laugh. I remember thinking: ‘I don’t know who that is, but I want to be her friend.’ I was so fascinated I forgot to cry.

I stood up and said, ‘Do you need any help with your bags?’

‘Oh yes!’ she said. ‘Actually, you are sitting on my doorstep.’

‘So, why were you crying?’ The ship woman said in her bright pink kitchen. It transpired that she was called Isabella Blow; she was contributing editor at Vogue and something of a fashion maverick. We’d put the bags down and she was making tea in a proper teapot.

‘I was crying about my future.’ I said heavily. ‘My mother doesn’t understand me. I don’t know what I’ll do. Oh, it’s so awful.’

‘Oh don’t worry about that. Pfff!’ she said. ‘Do you want to be a model?’

If it had been a film, there would have been the audible ting of a fairy wand. I looked at her incredulously. ‘Yes,’ I said, thinking of avoiding the purdah of shorthand. My next question was, ‘Are you sure?’

‘Now put on some lipstick and we’ll tell your mother we’ve found you a career’

The ‘Are you sure?’ didn’t spring from some sly sense of modesty; it was brutal realism. And not of the usual model standard ‘I was such an ugly duckling at school, and everyone teased me about how painfully skinny I was’ kind.

Bar my height, I couldn’t have looked any less like a model. I had enormous tits, an even bigger arse and a perfectly round face with plump, smiling cheeks. The only thing I could have possibly shared with a model was my twisted predilection for chain smoking.

But for sweet Issy, as I came to know her, none of this posed a problem. She saw people as she chose to see them; as grander cinematic versions of themselves.

‘I think,’ she said, her red lips a post-box stamp of approval, ‘I think you’re like Anita Ekberg.’ I pretended I knew whom she was talking about.

‘Ah yes. Anita Ekberg.’ I said.

‘Now put on some lipstick and we’ll go and find your mother and tell her we’ve found you a career.’

We celebrated our fortuitous meeting, with my now mollified mother in tow, at a Japanese restaurant in Mayfair, toasting my possible new career with a wealth of sushi and tempura.

‘Gosh, you do like to eat,’ Issy said, eyes wide, watching as my chopsticks danced over the plates. I would have said yes but my mouth was full.

Social activities in England often revolve around the tradition of the nursery tea. I was deeply keen on tea, but as an only child I was not at all keen on having to share either my toys or my food.

‘You must learn to share. It’s a very nasty habit, selfishness,’ Maureen, my Scottish nanny said, her grey eyes fixed on me in a penetrating way.

‘Urgh. It’s so unfair!’ I would cry, scandalized by the injustice of having to watch impotent as other children, often strangers, were allowed to torture my dolls and eat all the salt and vinegar crisps for the mere reason that ‘they can do what they want—they are your guests.’

But I didn’t invite them! You did. I don’t want them messing up my dressing-up box and smearing greasy fingers on my best one-eyed doll, or asking to see her ‘front bottom’. I don’t want friends who say ‘front bottom’. I want to play Tarzan and Jane with Dominic from next door, who has brown eyes and kissed me by the compost heap. I don’t want to be the ugly stepsister in the game, I want to be Cinderella! No, I’m not tired. I might go to my room now and listen to Storyteller. They can stay in the playroom on their own.

When I was six, my friend Ka-Ming came for tea. There was macaroni and cheese, and for pudding, yoghurt. Maureen announced in her buttery burr that there were only two yoghurts, chocolate and strawberry, on which Ka-Ming, as the guest, got first dibs. Agonizing as Ka-Ming slowly weighed up the boons of each flavour, I excused myself and ran to the playroom, where the wishing stone my grandmother Gee-Gee had found on the beach sat on the bookshelf. I had one wish left.

‘Please, wishing stone and God, let her not pick the chocolate yoghurt, because that is the one I want.’ I cradled the stone, hot in my palm.

I walked into the kitchen to find Ka-Ming already eating the strawberry yoghurt with enthusiasm. The chocolate Mr Men yoghurt sat sublime on my plate. This turn of fate cemented my belief that if you wish for something hard enough, as long as it doesn’t already belong to somebody else you tend to get it.

At ten, to my great dismay, I was sent to boarding school. I recalled the permanent midnight feasts in Enid Blyton books, and reckoned that this was the sole pro in an otherwise dismal situation. Yet on arrival I realized that the halcyon midnight feasts were a myth. The reality was fried bread swimming its own stagnant grease, powdered mashed potatoes, bright pink gammon, gristly stew, grey Scotch eggs and collapsed beetroot, which I was made to eat in staggering quantity.

The consolation prize when home from boarding school was picking a Last Supper. Last Suppers were cooked the final night of the school holidays by my mother at her bottle-green Aga; a balm to the palate before another term of unspeakably horrible food. I chose these suppers as if I was dining at the captain’s table on the Titanic—beef consommé, roast chicken wrapped in bacon with tarragon creeping wistfully over its breast, potatoes golden and gloriously crispy on the outside and flaking softly from within, and peas buttered and sweet, haloed by mint from the garden. Puddings were towering, trembling creations: lemon mousse, scented with summer; chocolate soufflés, bitter and proud.

We were grumpily ambivalent about the food at school; the English as a rule aren’t a race of protesters, particularly the ten-year-olds. School food was meant to be bad, that was its role before the advent of Jamie Oliver and his luscious organic, sustainable school dinners. There was the merest whiff of protest during the salmonella crisis in the late eighties, when some rebel chalked ‘Eggwina salmonella curry’ over the curried eggs listing on the menu board and got a detention for their efforts, but that was about as racy as it ever got.

I left boarding school at twelve, and we moved from starchy London to svelte New York. It was in this year that food first became something other than what you ate of necessity, boredom or greediness. I noticed that food contained its own brand of inherent power, certainly where adults were concerned. Women in New York talked about food and how to avoid it all the time. Their teenage progeny religiously counted fat grams, while the mothers went to see a tanned diet guru named Dr R, who provided neat white pills and ziplock bags for snacks of mini pretzels, asking them out for fastidious dinners where he monitored their calorie consumption. If they were lucky they might get a slimline kiss at the end of the evening, the bow of his leonine head offering dietary benediction. It was a savvy way of doing business; Dr R had a repeat clientele, as all the divorced mums were in love with him, staying five pounds over their ideal weight in order to prolong both that coveted dinner and his undivided attention.

I loved New York, loved its fast glittery shininess and sophistication, which was the polar opposite of the dowdy certainty of English boarding school. At my new school, my ineptitude with maths was greeted with such bolstering and enthusiasm that, for a brief blissful period, I was almost good at it.

In our biology class we read about the perils of anorexia. We learnt the signs to be wary of: secrecy, layers of clothing, blue extremities, pretending to have eaten earlier, cessation of menstruation, hair on the body, compulsive exercise.

My taste buds awoke from their slumber with the tenacity of Rip Van Winkle

We were eagle-eyed mini detectives, each classmate a suspect. After these sessions we didn’t see the irony in spending the whole of lunchtime talking about how many calories were in a plain bagel and who looked fat in her leotard. Awareness of eating disorders seemed American-specific; my friends in England were baffled by it.

‘Isn’t Anna Rexia a person?’ My best friend asked me on a crackling transatlantic line.

‘Duh.’ I said.

There was a pause.

‘That’s really awful. Why would anyone not want to eat when they were hungry?’

Cafeteria food in America was even worse than in England; gloopy electric-orange macaroni cheese, iron-tasting chocolate milk and ‘pudding’, a gelatinous mess meant to be related to vanilla in some way. I stuck to wholewheat bagels with cream cheese and tomatoes, because that was low-fat, and the then wisdom told us that low-fat was the way forward. On a Friday morning we were allowed to bring breakfast to school and eat it in our first class as a treat. I bought these breakfasts from the deli on the corner and did consider them treats; a fried egg sandwiched in a croissant and milky coffee (made with skimmed milk, of course) seemed deliciously adult and forbidden.

I shaved my legs for the first time at thirteen without permission and left ribbons of skin in the bath with my shaky novice hand. My mother came in and shook her head and said sadly, ‘Now you’ve started there’s no going back. That’ll be waxing for the rest of your life, my darling.’

I wondered how I might look to other people in a swimsuit, as during the summer there were pool parties where there were boys, and, perhaps even more scary, the narrow eyes of the other girls. It seemed much more complicated territory than my English boarding school, where everyone was blue from cold, clad in the same troll-like, unflattering regulation green. These golden girls wore tiny bikinis and had manicures and pedicures.

In the absence of hearty boarding school stodge and endless picking, my body had willowed. My legs were long; my skirts were short. I was a wisp with a wasp waist and pertly-chested to boot. I joined the chattering lunchtime throng, reading food labels as if they were Dostoevsky, pretending to understand, while at home I tore up steps on the Stairmaster as Jason Priestly twinkled at me from the television.

For reasons complicated and long, we left the sophisticated city when I was fourteen and fell heavily down to earth, onto England’s sodden soil, in 1991. No one seemed to have heard of ‘low-fat’ in England, not even in London where I was now at day school. They didn’t seem to care all that much. I tried for a few gruelling months to avoid the fat in food I’d learnt to be careful of, but it just kept coming back, persistent as a lover spurned.

I eventually surrendered on a half-term holiday in France with school friends who were eating their croissants and drinking their full-fat milk hot chocolate with deep abandon. Having ascertained that there really was no skimmed milk in the house (or indeed the country), I took the plunge. But oh! How delicious! My taste buds awoke from their New York slumber with the tenacity of Rip Van Winkle and they never slept again.

My body responded, and how; my cheeks plumped up like an indolent Matisse lady’s. On the street, my complicated curves and awkward wiggle sent a message that my brain and heart could not keep up with. Grown men called out to me; dark adult things in sly tones. I found this unsettling and felt naked even when I was dressed. Yet I dressed the part of the vixen in viciously-heeled shoes, breasts jutting forward proudly, betrayed only by my eyes. I was constantly followed home from school, and flashed at on the bus. My mother despaired and sent me to a progressive boarding school in Hampshire, surrounded by fields, where I could stomp around in my inappropriate clothing without being accosted by potential rapists. We lived on bread, and I filled myself brimful with it; warm and soft from the local bakery, covered in butter and Marmite.

Because of my school’s nice progressive nature, there was an abundance of personal choice and options. I discovered one could opt out of games and do something called ‘Outdoor Work’, so I opted out and tottered off to the woods in my suede miniskirts, lamely clutching a saw as I pretended to erect fences with the boys who still played dungeons and dragons. Our fences were spindly rickety efforts and our pig-tending was not much better.

On Wednesday we had a half-day of school to make up for the fact that we had school on Saturday and we were allowed to go into the nearby town in the afternoons, as long as we stayed clear of the pub. My interest in the pub was cursory. On Tuesday nights I planned epic gastronomic excursions, formulating the menu of what and where I would eat, the conclusion invariably involving an epic fiesta of cake and clotted cream.

Unsurprisingly, at boarding school I gained two stone. It happened quite by accident, and I didn’t even notice to begin with, but you can’t exist on bread and cake, with your sole exercise taking the form of watching other people build things, and stay thin. It didn’t occur to me how I could have contributed, or that I could do anything about any of it.

I just thought it was yet another adolescent unfairness foisted upon me. I ate more cake, read tragic French novels and hated the fields and stupid fences I was surrounded by. I longed for London, a minor Parisian appetite, lithe limbs, complication and Chantal Thomas knickers. Mercifully, the knowledge of how to acquire such things remained totally out of my reach.

My country sojourn over, I arrived back in London at sixteen with child-bearing hips and a trunk full of smocks. Everyone pretended not to notice. Sixth form was in Golders Green, and instead of café dining once a week on a Wednesday, planning lunch in the local establishments became a blissful daily affair. This is where all of my summer babysitting money went. At the bottom of Golders Hill, near the station, there was an amazing kosher deli where I ordered fresh bagels, sweet and doughy inside, smothered with thick cream cheese and smoked salmon. In Golders Hill Park, it was the sweet little Italian café where you could get a plate of al dente penne with a smoky tomato sauce and dear little cream-filled pastries for pudding. The pub at the top of the hill was all about jacket potatoes and a fine ploughman’s. But what jacket potatoes—twice-baked and filled with butter, gruyère and watercress, or the alternative: tuna, mayonnaise and sweetcorn. I think I tried to go on a diet once, and it involved, from what I can remember, eating a lot of brown rice and apples and lethicin, because a friend of my mother’s told me that they all lived on it in the seventies and that it melted fat clean away. In the sixth form games were no longer compulsory, and I began to feel the same way about school, causing an academic rift that I rue to this day.

Between school and modelling, before I met Isabella, I was first a nanny, then a waitress. Both were perilous where food was concerned. As a nanny, I was constantly picking at leftover fishfingers, Twiglets, egg sandwiches and Victoria sponge. The two girls I looked after were incredibly sweet: a round baby and a six-year-old with a voice like Marianne Faithfull. We went to lots of rather posh tea parties where the mothers greeted me as ‘Nanny’. I adored the little girls but was a bit hopeless really; not ironing their clothes, taking naps with them and trying on their mother’s scent when she was out. I was very much eighteen. We did, however, make each other laugh, and I loved Jaffa Cakes as much as they did.

I tottered off to the woods, lamely clutching a saw

And not for me the kind of waitressing job where I ran on skinny legs around a steamy frantic environment, collapsing at the end of a twelve-hour shift in sheer anaemic exhaustion. No, I went to work the 7.00 am shift in a coffee-shop bakery after the baking had already taken place. Thus, my arrival coincided happily with things coming out of the oven; a muffin with apple butter, a dark molasses banana bread. I think it was my all-time favourite job. It involved chatting, smiling, eating and concocting lovely coffee-based milkshakes which I would sip through the day. I was an awful waitress, because I was clumsy and could never remember anyone’s order. But they were terribly sweet there, and I learnt how to sweep a floor properly, and that you cannot wear five-inch peep-toed mules to waitress in.

I was dripping in diamonds and not much else

When I began modelling after those brief jobs, I was completely unprepared for the onslaught of curiosity it carried with it. I was in that funny teenage place of being both very aware of, and yet somehow forgetting I had a body. I wanted to look the same as my friends; I wanted to be able to borrow their clothes. Beyond that, I didn’t think about it too deeply.

Issy had never told me to lose weight; she had just said rather vaguely, ‘Now, my love; no more chips and puddings for you, and always wear a good bra and red lipstick.’ My concession to this advice was a DIY diet; eating instant powdered soup with dry pitta bread for three days, which was revolting, and certainly had no effect. I ended up being measured for a bra at Rigby and Peller, which had an infinitely more tangible result than the soup, and also developed a lifelong love affair with Yves Saint Laurent’s Rouge Pur, which smells of roses.

It was Issy who introduced me to Sarah Doukas, the founder of Storm Model Management, and when she signed me, weight loss was nowhere on the day’s agenda. Sarah is famously visionary; she discovered Kate Moss at JFK airport when she was fourteen and manages her to this day. With her customary canniness, she saw that there might actually be a place for me in fashion, given the vocal protest the media were making against the so-called ‘heroin chic’ look that was defining style. The timing, and her instinct, made a happy marriage to set the scene for what was about to happen.

My first job was being photographed nude by Nick Knight for ID magazine. They gave me five-inch long silver nails, silver contact lenses and a canvas of skin powdered silver. I don’t remember feeling naked; I felt like an onlooker, such was the transformative power of the hair and make-up, which took four hours. The overriding memory I have of that day is of being turned into someone else; some alter ego with comic-book curves and a rapacious smile. Being naked seemed almost incidental. A few hours later I was sent in a cab up to Park Royal to be shot by David La Chapelle for Vanity Fair in a portfolio about ‘Swinging London’, this time clad in a string bikini. When I went home late that night, I didn’t wash my make-up off because I wanted to wake up looking like that forever. Of course the next morning I was a smeared shell of a creature, my sheets covered in silver dust.

A few weeks later, I boarded a train to Paris, carrying nothing but a little basket with my nightdress, knickers and a toothbrush, and went straight from the Gare du Nord to the house of Karl Lagerfield, who was shooting a story for German Vogue about King Farouk. Gianfranco Ferré was playing the part of the erstwhile king, and I his bawdy American mistress. I was dripping in diamonds and not a great deal else. I felt incredibly shy around Mr Lagerfield, who was kind yet reticent behind his fan, until he roared with laughter, pinched my cheeks and kissed me like an uncle. We stopped for a proper French lunch, a stew heavy with red wine, oozing cheese and crusty bread and little pots of dense, dark chocolate for pudding. I was in heaven. The shoot went on long into the night, and after everyone else had gone home he photographed me waltzing around his beautiful library, which shone with swathes of waxy lilies and hundreds of candles. At 3.00 am I walked across the street to the old-fashioned hotel where I was staying, and I lay in bed with my eyes wide open, unable to summon sleep. There was so much to absorb and evoke, from the books that lined the walls from floor to ceiling, to the church-like smell of the lilies, the cool of the diamonds as they slipped around my neck, the food…

People had noticed me. Big women from all over the world wrote me congratulatory letters, commending my big bold form. Morning television shows wanted to interview me. Newspapers breathlessly reported my strange fleshy phenomena; a welcome backlash, finally, against the x-ray fashion industry. In the wake of the very angular, it seemed people wanted an anti-waif; a sensual woman who indulged in whatever she wanted, whenever she wanted it. By default, this became me. But reflection on what it represented and what it might mean had escaped me; no longer reliant on waitress’s wages, I was too busy skipping around London, Paris, New York and Milan, spending my modelling money in posh restaurants, city appropriate. I went to Nobu for the first time and nearly died with pleasure—that black cod! In Italy it was risotto, in Paris remoulade, and New York was just a culinary world mecca, full stop.

I remember doing shows in the early days, happily squeezed into some mini little thing. Although a walk up and down a runway is over in minutes, you can register the faces of those you walk by in slow motion. I produced such a strange mixed reaction, one that was palpable. The more formidable fashion editors would sit there with their arms tightly crossed, looking embarrassed and rolling their eyes. Others would cheer and shout. The photographers at the end of the runway would sometimes catcall and whistle. It had been a long time since the advent of tits in fashion, so they were pretty enthused. I found a sort of sad teenage validation in this—not particularly thought-out or examined—something along the lines of ‘It’s men, whistling at me. They seem to fancy me. Hurrah! That must mean I’m kind of sexy.’

Every woman in my family had been through a tricky adolescent over-spilling phase. The difference with mine was that it became both representative and a matter of public record, rather than something to look back on with tender mirth when presented with a family album. We always joked as a family about our greediness. We described events by what we ate. There was and is, a total ease and pleasure around food and cooking. My path has been a funny one; having come from such a background, to then find myself at a formative age dropped into the middle of an industry not exactly renowned for its epicurean appreciation. There’s something sort of fun and subversive about it. It was a slightly wiggly trajectory, but one full of interesting stuff.

And guess what? I’m now right back where I was at seven, bar the penchant for coral lipstick and bad hats. I just couldn’t get away from the siren call of the kitchen that is an inherent part of me. The kitchen of which I speak is both literal and metaphoric. It’s the sum of what I’ve learnt so far, and am still learning.

This kitchen is a gentle relaxed one, where a punishing, guilt-inducing attitude towards food will not be tolerated. In this kitchen we appreciate the restorative powers of chocolate. The kitchen would have a fireplace, and possibly a few dogs from Battersea Dogs’ Home curled up next to it. There might be a small upright piano by the window, with an orchid that doesn’t wither as soon as I look at it. On long summer days, the doors to this kitchen are thrown open, while a few lazy, non-stinging bees mosey by. Children stir. When it rains, there is room in this kitchen for reading and a spoon finding its way into the cake mix. Serious cups of tea are drunk here; idle gossip occurs, balance and humour prevail. It’s the kitchen of my grandparents’, but with some Bowie thrown in. It is lingering breakfasts, it is friends with babies on their knees, it is goodbye on a Sunday with the promise of more. This kitchen is where life occurs; jumbled, messy and delicious.

There is room in this kitchen for a spoon finding its way into the cake mix

It is lovely.