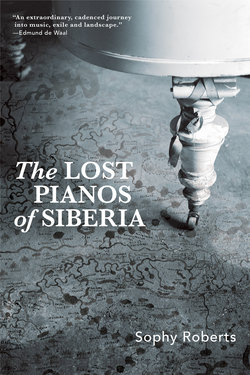

Читать книгу The Lost Pianos of Siberia - Sophy Roberts - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Music in a Sleeping Land: Sibir

EARLY ON IN MY travels in Siberia, I was sent a photograph from a musician living in Kamchatka, a remote peninsula which juts out of the eastern edge of Russia into the fog of the North Pacific. In the photograph, volcanoes rise out of the flatness, the scoops and hollows dominated by an A-shaped cone. Ice loiters in pockets of the landscape. In the foreground stands an upright piano. The focus belongs to the music, which has attracted an audience of ten.

A young man wearing an American ice-hockey shirt crouches at the pianist’s feet. With his face turned from the camera, it is difficult to tell what he is thinking, if it is the pianist’s music he finds engaging or the strangeness of the location where the instrument has appeared. The young man listens as if he might belong to an intimate gathering around a drawing-room piano, a scene that pops up like a motif in Russia’s nineteenth-century literature, rather than a common upright marooned in a lava field in one of the world’s most savage landscapes. There is no supporting dialogue to the photograph, no thickening romance, as happens around the instruments in Leo Tolstoy’s epic novels. Nor is there any explanation about how or why the piano ended up here in the first place. The image has arrived with no mention of what is being played, which is music the picture can’t capture anyway. Yet all sorts of intonations fill the word ‘Siberia’ written in the subject line of the email.

Siberia. The word makes everything it touches vibrate at a different pitch. Early Arab traders called Siberia Ibis-Shibir, Sibir-i-Abir and Abir-i-Sabir. Modern etymology suggests its roots lie in the Tatar word sibir, meaning ‘the sleeping land’. Others contend that ‘Siberia’ is derived from the mythical mountain Sumbyr found in Siberian-Turkic folklore. Sumbyr, like ‘slumber’. Or Wissibur, like ‘whisper’, which was the name the Bavarian traveller Johann Schiltberger bestowed upon this enigmatic hole in fifteenth-century cartography. Whatever the word’s ancestry, the sound is right. ‘Siberia’ rolls off the tongue with a sibilant chill. It is a word full of poetry and alliterative suggestion. But by inferring sleep, the etymology also undersells Siberia’s scope, both real and imagined.

Siberia is far more significant than a place on the map: it is a feeling which sticks like a burr, a temperature, the sound of sleepy flakes falling on snowy pillows and the crunch of uneven footsteps coming from behind. Siberia is a wardrobe problem – too cold in winter, and too hot in summer – with wooden cabins and chimney stacks belching corpse-grey smoke into wide white skies. It is a melancholy, a cinematic romance dipped in limpid moonshine, unhurried train journeys, pipes wrapped in sackcloth, and a broken swing hanging from a squeaky chain. You can hear Siberia in the big, soft chords in Russian music that evoke the hush of silver birch trees and the billowing winter snows.

Covering an eleventh of the world’s landmass, Siberia is bordered by the Arctic Ocean in the north and the Mongolian steppe in the south. The Urals mark Siberia’s western edge, and the Pacific its eastern rim. It is the ultimate land beyond ‘The Rock’, as the Urals used to be described, an unwritten register of the missing and the uprooted, an almost-country perceived to be so far from Moscow that when some kind of falling star destroyed a patch of forest twice the size of the Russian capital in the famed ‘Tunguska Event’ of 1908, no one bothered to investigate for twenty years. Before air travel reduced distances, Siberia was too remote for anyone to go and look.

In the seventeenth century, wilderness was therefore ideal for banishing criminals and dissidents when the Tsars first transformed Siberia into the most feared penal colony on Earth. Some exiles had their nostrils split to mark them as outcasts. Others had their tongues removed. One half of their head was shaved to reveal smooth, blue-tinged skin. Among them were ordinary, innocent people labelled ‘convicts’ on the European side of the Urals, and ‘unfortunates’ in Siberia. Hence the habit among fellow exiles of leaving free bread on windowsills to help bedraggled newcomers. Empathy, it seems, has been seared into the Siberian psyche from the start, with these small acts of kindness the difference between life and death in an unimaginably vast realm. Siberia’s size also stands as testimony to our human capacity for indifference. We find it difficult to identify with places that are too far removed. That’s what happens with boundless scale. The effects are dizzying until it is hard to tell truth from fact, whether Siberia is a nightmare or a myth full of impenetrable forests and limitless plains, its murderous proportions strung with groaning oil derricks and sagging wires. Siberia is all these things, and more as well.

It is a modern economic miracle, with natural oil and gas reserves driving powerful shifts in the geopolitics of North Asia and the Arctic Ocean. It is the taste of wild strawberries sweet as sugar cubes, and tiny pine cones stewed in jam. It is home-made pike-and-mushroom pie, clean air and pure nature, the stinging slap of waves on Lake Baikal, and winter light spangled with powdered ice. It is land layered with a rich history of indigenous culture where a kind of magical belief-system still prevails. Despite widespread ecological destruction, including ‘black snow’ from coal mining, toxic lakes, and forest fires contributing to smoke clouds bigger than the EU, Siberia’s abundant nature still persuades you to believe in all sorts of mysteries carved into its petroglyphs and caves. But Siberia’s deep history also makes you realize how short our human story is, given the landscape’s raw tectonic scale.

In Siberia’s centre, a geographical fault, the Baikal Rift Zone, runs vertically through Russia to the Arctic Ocean. Every year the shores around Lake Baikal – the deepest lake on Earth, holding a fifth of the world’s fresh water – move another two centimetres apart, the lake holding the kinetic energy of an immense living landscape about to split. It is a crouched violence, a gathering strain, a power that sits just beneath the visible. The black iris of Russia’s ‘Sacred Sea’ is opening up, the rift so significant that when this eye of water blinks sometime in the far future, Baikal could mark the line where the Eurasian landmass splits in two: Europe on one side, Asia on the other, in one final cataclysmic divorce. Above all, Baikal’s magnificence reasserts the vulnerability of man. Beneath the lake’s quilt of snow in winter lies a mosaic of icy sheets, each fractured vein serving as a reminder that the lake’s surface might give way at any moment. Fissures in the ice look like the surface of a shattered mirror. Other cracks penetrate more deeply, like diamond necklaces suspended in the watery blues. The ice tricks you with its fixity when in fact Baikal can be deadly. Just look at how it devours the drowned. In Baikal there is a little omnivorous crustacean smaller than a grain of rice, with a staggering appetite. These greedy creatures are the reason why Baikal’s water is so clear: they filter the top fifty metres of the lake up to three times a year – another strange endemic aberration like Baikal’s bug-eyed nerpa seals, shaped like rugby balls, whose predecessors got trapped in the lake some two million years ago when the continental plates made their last big shift. Either that or the nerpa are an evolution of ringed seal that swam down from the Arctic into Siberia’s river systems and got stuck – like so much else in Siberia, unable to return to their homeland, re-learning how to survive.

Because Siberia isn’t sleeping. Its resources are under immense pressure from a ravenous economy. Climate change is also hitting Siberia hard. In the Far North, the permafrost is melting. More than half of Russia balances on this unstable layer of frozen ground, Siberia’s mutability revealed in cracks that slice through forlorn buildings, and giant plugs of tundra collapsing without a grunt of warning. Bubbles formed of methane explode then fall in like soufflés. But no one much notices – including Russians who have never visited, whose quality of life owes a debt to Siberia’s wealth – because even with modern air travel there are Siberians living in towns who still refer to European Russia as ‘the mainland’. They might as well be marooned on islands. Take Kolyma in Russia’s remote north-east, flanking an icy cul de sac of water called the Sea of Okhotsk. This chilling territory, where some of the worst of the twentieth-century forced-labour camps, or Gulags, were located, used to be almost impossible to access except by air or boat. Even today, the twelve hundred miles of highway linking Kolyma to Yakutsk, which is among the coldest cities on Earth, are often impassable. In his unflinching record of what occurred in the camps, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s choice of words – The Gulag Archipelago – is therefore rooted in fact, even if the phrase carries an immense metaphorical weight.

The Soviet Gulag – scattered throughout Russia, not just Siberia – was different from the Tsarist penal exile system which came before the 1917 Revolution, although the two are often confused. The Tsars could banish people to permanent settlement in Siberia, as well as condemn them to hard labour. Under the Soviets, the emphasis was on hard-labour camps only, wound together with curious methods of ‘cultural education’. Once your sentence was up (assuming you survived it), you could usually return home, though there were exceptions. Both systems had a great deal of brutality in common, with the Tsarist exile system turning Siberia into a prodigious breeding ground for revolutionary thought. Trotsky, Lenin, Stalin – they all spent time in Siberia as political exiles before the Revolution. So did some of Russia’s greatest writers, including Fyodor Dostoevsky, who in the mid-nineteenth century described convicts chained to the prison wall, unable to move more than a couple of metres for up to ten years. ‘Here was our own peculiar world, unlike anything else at all,’ he wrote – ‘a house of the living dead.’

Yet under winter’s spell, stories about the state’s history of repression slip away. Siberia’s summer bogs are turned into frosted doilies and pine needles into ruffs of Flemish lace. The snow dusts and coats the ground, swirling into mist whenever the surface is caught by wind, concealing the bones of not only Russians but also Italians, French, Spaniards, Poles, Swedes and many more besides who perished in this place of exile, their graves unmarked. In Siberia, everything feels ambiguous, even darkly ironic, given the words used to describe its extremes. Among nineteenth-century prisoners, shackles were called ‘music’, presumably from the jingle of the exiles’ chains. In Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago, to ‘play the piano’ meant having your fingerprints taken when you first arrived in camp.

But there is also another story to Siberia. Dotted throughout this land are pianos, like the humble, Soviet-made upright in the photograph of a Kamchatka lava field, and a few modern imported instruments. There is an abundance of beautiful grand pianos in a bitterly cold town called Mirny – a fifties Soviet settlement enriched by the largest open-cast diamond mine in the world – and more than fifty Steinway pianos in a school for gifted children in Khanty-Mansiysk at the heart of Western Siberia’s oil fields. Such extravagances, however, are few and far between. What is more remarkable are the pianos dating from the boom years of the Empire’s nineteenth-century pianomania. Lost symbols of Western culture in an Asiatic realm, these instruments arrived in Siberia carrying the melodies of Europe’s musical salons a long way from the cultural context of their birth. How such instruments travelled into this wilderness in the first place are tales of fortitude by governors, exiles and adventurers. The fact they survive stands as testimony to the human spirit’s need for solace. ‘Truly, there would be reason to go mad if it were not for music,’ said the Russian pianist and composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky.

Russia’s relationship with the piano began under Catherine the Great – the eighteenth-century Empress with a collector’s habit for new technologies, from musical instruments to her robotic timepiece made up of three life-size birds: an owl which twists its head, a peacock which fans its tail (you can almost see the breast rising for a breath), and a rooster which crows on every hour.* Catherine was also the inheritor of Peter the Great’s Westernizing legacy when his founding of St Petersburg in 1703 first ‘hack[ed] a window through to Europe’. Sixteen years after Peter’s death came the Empress Elizabeth, another modernizer, who introduced a musical Golden Age with her affection for European opera. Elizabeth’s extravagant spending habits on Italian tenors and French troupes affected the musical tastes of the Russian elite – a trend which continued after 1762 when Catherine became Empress and augmented Elizabeth’s mid-century influence and generous patronage of the arts. European culture thrived in St Petersburg, even if the deeper questions surfacing in Western Europe – in books by, for example, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the philosopher whose theories about the pursuit of individual liberty and the natural equality of men inspired a generation of Romantics – had no place in the Russian court.

While revolution brewed in France, Catherine remained entirely deaf to criticism around Russia’s oppressive system of serfdom, which was such a significant source of imperial wealth. Russian men, women and their children born into feudal bondage were not only vassals employed to work the fields but were also trained as singers and dancers to lighten the manorial gloom. As instrumental music developed, serf orchestras became a distinctly Russian phenomenon, with one well-known musical fanatic of Catherine’s time insisting his entire staff address him only in song. Others were sent abroad to study music – a fashion which continued into the nineteenth century. In 1809 when two of these serf musicians were unhappily recalled to Russia from their training in Leipzig, they took their revenge, and murdered their master by cutting him up into pieces in his bedroom. In Leipzig, not only had they heard beautiful music; they had also tasted liberty.

Punishment was Siberia, where unlucky serfs were routinely exiled without trial for far more trivial transgressions, from impudence to taking snuff. When the dissident Aleksandr Radishchev chronicled the horrors of the Russian system of feudal slavery in his 1790 book, A Journey from St Petersburg to Moscow, Catherine cranked up her response.* She exiled her most high-profile naysayer to the penal colony of Siberia, which was rapidly expanding its barbaric shape. When Austria, Prussia and Russia began to carve up Poland and what became known as the Western Provinces – a region that roughly included Lithuania, Ukraine and Belarus – Siberia received the first trickle of educated Polish rebels.* Presiding over their fate as exiles were Catherine’s governors, one or two of whom took keyboard instruments with them to their postings in the back of beyond.

This was a time when the instrument was still developing, when even the names of keyboard instruments betrayed an identity problem. The German word Klavier sometimes referred to a harpsichord, spinet, virginal or clavichord. The word ‘clavichord’, if correctly used, referred to an instrument which, like the piano, used a percussive hammer action on the strings rather than the pluck of a harpsichord’s plectrum. Sometimes called ‘the poor man’s keyboard’, it was an instrument which could respond to a player’s fingers, their trembling, sympathetic pauses and emotive intent: ‘In short, the clavichord was the first keyed instrument with a soul.’ Confusingly, however, ‘clavichord’ sometimes also referred to the ‘fortepiano’ – the instrument, which translates as ‘loud-soft’, devised by the Italian maker Bartolomeo Cristofori for the Medici family at the turn of the eighteenth century. What made Cristofori’s invention groundbreaking wasn’t just the piano’s relative portability (unlike an organ): its improved dynamics and musical expression created the illusion there was an entire orchestra in the room.

‘Until about 1770 pianos were ambiguous instruments, transitional in construction and uncertain in status,’ observes one of the twentieth century’s foremost historians on the subject. Catherine’s treasured square piano, or piano anglais, is the perfect example of this evolutionary flux. In 1774, at the dawn of the piano’s vogue, the Empress ordered this new-fangled keyboard instrument from England, made by London’s first manufacturer, a German immigrant called Johann Zumpe. It was the instrument du jour, owned by everyone from Catherine’s great friend the French philosopher and lexicographer Denis Diderot, whose Encyclopédie declared keyboard playing a crucial accomplishment in the education of modern women, to English royalty. Within ten years of its invention, versions of this instrument were being made in England, France, Germany and America. According to one contemporary British composer, Zumpe couldn’t make his pianos fast enough to gratify demand.

Catherine’s 1774 piano anglais, its decorative cabinetry as pretty as a Fabergé egg, now stands behind red rope in Pavlovsk, an eighteenth-century Tsarist pleasure palace outside St Petersburg which functioned as one of Russia’s most important centres of musical life. The piano is displayed alongside a Sèvres toilet set gifted to the imperial family by Marie Antoinette. The Zumpe, which would have been a novelty at the time, has a certain sweetness when playing a slow adagio, but there is also an older, courtlier twang and a tinny thud of keys. Only when the technology’s powerful hammer action improved, thicker strings were stretched to higher tensions, and the pedals were finessed to allow for even better control of the ‘loud-soft’ expression, would the piano’s potential expand into the instrument we know today. This next dramatic phase in piano technology, thriving in the first three decades of the nineteenth century, pushed the instrument into concert halls all over Europe as its more robust mechanisms became better able to tolerate the passions of the virtuoso. In 1821, the French factory Erard patented the ‘double escapement’ action, which allowed for much more rapid repetition of a note without releasing the key. This was when the piano also began to migrate more widely – a trend witnessed by James Holman, a blind Englishman who travelled to Siberia in 1823 for no other reason, it would seem, than to furnish himself with a stack of drawing-room anecdotes. He wrote in his account: ‘One lady of my acquaintance had carried with her to the latter place, a favourite piano-forte from St Petersburg at the bottom of her sledge, and this without inflicting the least injury upon it.’

Violent. Cold. Startlingly beautiful. That stately instruments might still exist in such a profoundly enigmatic place as Siberia feels somehow remarkable. It becomes nothing less than a miracle when one learns that not only did Catherine’s 1774 Zumpe survive a twentieth-century wartime sojourn in Russia’s terra incognita, but that other historic pianos are still making music in sleepy Siberian villages. Where wooden houses seem to cosy up together for warmth, there are pianos washed up and abandoned from the high-tide mark of nineteenth-century European romanticism. This was one of the most important periods in the popularization of the piano, when a new breed of virtuoso performer became its most convincing endorsement.

Soon after arriving in Russia in 1802, the Irish pianist John Field – the inventor of the nocturne, a short, dream-like love poem for the piano – could name his price as both a performer and a teacher in the salons of Moscow and St Petersburg. Field sounded the first chord, as it were, in the Russian cult of the piano, but it was the celebrity of the Hungarian Franz Liszt which turned the Russian love of the instrument into a fever in the 1840s.

Women grabbed at strands of Liszt’s iconic bobbed hair to wear close to their chest in lockets. Fans fought over his silk hankies, coffee dregs (which they carried about in phials) and cigarette butts. German girls fashioned bracelets from the piano strings he snapped and turned the cherry stones he spat out into amulets. In Vienna – one of the great capitals of European music – local confectioners sold piano-shaped biscuits iced with his name. When Liszt left Berlin for Russia in the spring of 1842, his coach was drawn by six white horses and followed by a procession of thirty carriages. When he played in St Petersburg in April, the infamous ‘smasher of pianos’ – a reputation derived from the broken instruments Liszt left in his wake – drew the largest audience St Petersburg had ever seen for such an event.

An 1842 drawing of Liszt playing to a frenzied Berlin crowd, the scene not unlike a modern rock concert.

Liszt leapt on to the stage rather than walked up the steps. Throwing his white kid gloves on to the floor, he bowed low to an audience who lurched from complete silence to thunderous applause, the hall rocking with adulation as he played on one piano, then another facing the opposite direction. At a performance for the Tsarina in Prussia two years earlier, Liszt had broken string after string in his tortured piano. In St Petersburg, his recital was somewhat more successful – a spectacular display of the instrument’s range, jamming rippling notes into music packed with an intense and violent beauty. When John Field heard Liszt perform, he apparently leaned over to his companion, and asked, ‘Does he bite?’ Liszt was considered ‘the past, the present, the future of the piano’, wrote one contemporary; his solo recital to a throng of three thousand Russians ‘something unheard of, utterly novel, even somewhat brazen . . . this idea of having a small stage erected in the very centre of the hall like an islet in the middle of an ocean, a throne high above the heads of the crowd’, wrote another witness to this groundbreaking event. Liszt’s talent was capable of instigating a kind of musical madness, according to Vladimir Stasov, the Russian critic present at Liszt’s St Petersburg debut. Stasov went with his friend Aleksandr Serov to hear him play:

We exchanged only a few words and then rushed home to write each other as quickly as possible of our impressions, our dreams, our ecstasy . . . Then and there, we took a vow that thenceforth and forever, that day, 8th April, 1842, would be sacred to us, and we would never forget a single second of it till our dying day . . . We had never in our lives heard anything like this; we had never been in the presence of such a brilliant, passionate, demonic temperament, at one moment lurching like a whirlwind, at another pouring forth cascades of tender beauty and grace.

Liszt’s Russian tour had a significant effect on the country’s shifting musical culture – not least the validation Liszt gave to Russia’s nascent piano industry when he played on a St Petersburg-made Lichtenthal in an important musical year. In 1842, Mikhail Glinka’s Ruslan and Lyudmila – considered the first true ‘Russian’ opera for its native character and melody – premiered in St Petersburg. Liszt, who developed a keen affection for Russian folk music, thought the opera marvellous.

While Glinka’s opera was influential, it was still the piano and the splendid character of the virtuoso which enthralled the aristocracy, with instruments being snapped up in Russia now they were no longer a technical rarity. ‘You will find a piano, or some kind of box with a keyboard, everywhere,’ observed one mid-century Russian journal writer: ‘If there are one hundred apartments in a St Petersburg building, then you can count on ninety-three instruments and a piano-tuner.’ It was the same story all over Europe. That same year, the London piano maker Broadwood & Sons was one of the city’s twelve largest employers of labour. Grand Tourists – upper-class men on a coming-of-age culture trip through Europe – couldn’t live away from home without a piano. According to a well-thumbed guidebook, How to Enjoy Paris in 1842, most English families who came to the city for any length of time would want to hire or buy a piano. In Britain alone, the five-year period from 1842 saw sixteen patents issued for new piano technology.

With every development in the instrument’s functionality, the piano’s increasingly expressive capacity was greeted with a flurry of composition. With an emerging merchant class hungry for new luxuries, state subsidies were encouraging a home-grown industry. Russian piano-making was thriving, an early Russian-made salon grand piano costing not much more than a couple of rows of seats at Liszt’s 1842 performance in St Petersburg.

A Russian family pictured with their piano in the 1840s, when the piano became an important symbol of prestige.

As the century progressed, piano technology kept improving, with iron (as opposed to wooden) frames, new ways of stringing, and the development of the upright piano – described by one historian as ‘a remarkable bundle of inventions’, its size and portability well suited to the homes of the swelling middle classes. In 1859, Henry Steinway, a German piano maker who emigrated to New York, patented the first over-strung grand piano, which gave concert instruments greater volume. A richly textured musical establishment evolved not just with piano-playing in Russia but across all sorts of musical genres and institutions – in opera, ballet, symphony orchestras, conservatories and amateur musical societies. Around the turn of the twentieth century, Russia’s contribution to classical composition was riding high. Tchaikovsky and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov had joined Europe’s first rank. Lumin aries among Russian piano-players included Anton and Nikolai Rubinstein, and Sergei Rachmaninoff. A Russian national style had fully developed, which was influencing (and even eclipsing) the rest of the Western world. Russia was winning accolades for its instrument-makers at the World Fairs.

St Petersburg-made Becker pianos on show at the Paris World Fair of 1878, with the Shah of Persia listening in to the demonstration. In 1900, the Fair’s Russian pavilion caused another sensation, with an advert for the new Trans-Siberian Railway. A painted panorama, scrolled past the windows of the display carriage, compressed the five-and-a-half-thousand-mile-long trans-Siberian journey into a famously pretty sales pitch. The reality, remarked some travellers, did not always prove quite so picturesque.

Then the chaos of the 1917 Revolution ruptured the country’s cultural patrimony. A number of high-profile musicians fled for Germany, France and America. As the Tsarist regime fell apart, Gobelin tapestries, even Van Dyck paintings, were scooped up by departing gentry and opportunistic foreigners in a hurry to leave town with whatever treasures they could salvage. Precious violins were sneaked out under greatcoats, and pianos were tied on top of trains fleeing Russia through Siberia into Manchuria and beyond.

In 1919, one of St Petersburg’s music critics sold his grand piano for a few loaves of bread. ‘Loot shops’ opened up in St Petersburg and Moscow to deal in objets d’art stolen from the rich. During the Russian Civil War, which lasted until 1922, manor houses were raided or burnt. In the aftermath, half-surviving instruments were reconstructed. Pianos were built with jumbled parts, such as a Bechstein keyboard on Pleyel legs.

Two decades later, during the Great Patriotic War, the country’s most significant national treasures were sent to Siberia for safekeeping, including state-owned instruments from Leningrad and Moscow, the country’s best ballerinas and Lenin’s embalmed corpse. Not long after, pianos taken from the USSR’s Western Front,* from the likes of Saxony and Prussia, ended up travelling eastwards with the country’s Red Army soldiers to adorn many a Siberian hearth. As the Nazis advanced, Russians fled their own cities on the European side of the Urals, the trauma of war driving civilians deeper into Siberia, sometimes with an instrument. Other pianos were lost to the German advance or chopped up into firewood. One piano, today in the hands of a well-known musician, was pushed up on its side to black out windows during the Siege of Leningrad when the Nazis starved the city in one of the darkest civilian catastrophes of a horrifyingly bloody century.

Meanwhile, the old expertise in Russian piano-making was changing with the politics. ‘Art belongs to the people,’ Lenin said in 1920: ‘It must have its deepest roots in the broad mass of workers. It must be understood and loved by them. It must be rooted in and grow with their feelings, thoughts and desires.’ The Soviet government encouraged the production of thousands of instruments, which were distributed through the USSR’s newly formed network of music schools. Piano factories opened in Siberia. Piano rental schemes were introduced for private citizens, with a buoyant market for uprights able to fit into snug Soviet apartments.

This dynamic musical culture, its provincial and social reach far exceeding the equivalent education systems in the West, fell away after 1991 when Boris Yeltsin became the first freely elected leader of Russia in a thousand years. Yeltsin immediately set about dissolving the Soviet Union by granting autonomy to various member states. He also overhauled government subsidies in the move to a free-market economy, inducing a chain reaction of dramatic hyperinflation, industrial collapse, corruption, gangsterism and widespread unemployment. As the masses crashed into poverty, the privatization of Russian industries benefitted a few friends of friends in government, who bought oil and gas companies at knock-off prices. Russia’s famous oligarchy was born at the same time as generations of communist ‘togetherness’ were overthrown.

Whether or not Yeltsin’s time was a good or a bad thing for Russians remains a moot point. For pianos, it was a catastrophe. The musical education system suffered. As a new rich evolved, tuners learned how to make a mint by doing up old instruments and selling them off as a kind of bourgeois status symbol. They painted broken Bechsteins white to suit an oligarch’s mansion, decorated them with gold leaf, and occasionally told tall stories about some kind of noble history to increase the piano’s value in a new and naive market. This was a time when Russia was giddy with opportunity and new ways of doing things. It was also a country demoralized by communism’s failure: many people wanted to believe in a rosier version of the past.

Numerous instruments were left to rot in Siberia, either too big to move from apartments, or ignored in the basements of music schools long after the funding had run out. Often all that is left of a piano’s backstory can be gleaned only from the serial number hidden inside the instrument – stories reaching back through more than two hundred years of Russian history. Yet there are also pianos that have managed to withstand the furtive cold forever trying to creep into their strings. These instruments not only tell the story of Siberia’s colonization by the Russians, but also illustrate how people can endure the most astonishing calamities. That belief in music’s comfort survives in muffled notes from broken hammers, in beautiful harmonies describing unspeakable things that words can’t touch. It survives in pianos that everyday people have done everything to protect.

In the summer of 2015, I encountered Russia’s piano history for the first time. It was something new for me: the mysterious, illogical power of an obsession when I started looking for an instrument in Siberia on behalf of a brilliant Mongolian musician. Part of me had always been intrigued by Siberia – a curiosity which had existed since my childhood, when the white space on my globe stretched further than my imagination was capable of. Like Timbuktu, or Ouagadougou, Siberia resonated in a way I couldn’t quite explain, with my bookcase telling the story of a bibliophile’s relationship with a place I assumed I would never visit. When I finally did, something else took hold – a kind of selfish madness to finish what I had started, while at the same time knowing that in a place as vast as Russia the finish might also never come. I began to make digressions into territory I didn’t expect pianos to ever lead me, travelling further and further from my home in England in pursuit of an instrument I don’t even play. It didn’t matter if causality started to fracture – from A, I had to go to C because of what B had told me – because I had begun to fall for Siberia’s unpredictability, for the serendipitous connections and untold experiences that belong to people who make up one of the greatest storytelling nations in the world. I soon realized that what is missing can sometimes tell you more about a country’s history than what remains. I also learned that Siberia is bigger, more alluring and far more complicated than the archetypes might suggest – much bigger, in fact, than all the assumptions I had made when my plans began to germinate, then proliferate, and I found myself caught up in the momentum of travelling a ravishingly surprising place.

All this because of a friendship which formed back in the summer of 2015 with a young Mongolian woman called Odgerel Sampilnorov. Odgerel and I were both staying with a German friend, Franz-Christoph Giercke, in Mongolia’s Orkhon Valley, close to Karakorum, the site of the historic capital of Genghis Khan’s empire, not far from the border with Siberia. The Giercke family spent their summers in a ridgeline of gers – the nomads’ round-shaped wood-and-canvas tents, which were pitched a long way from where the road runs out in the fenceless steppe. Odgerel had formerly worked as a piano teacher to Giercke’s daughter and her Mongolian cousins, using an old instrument he had trucked in from the modern capital, Ulaanbaatar.

‘When we first met, Odgerel was only nineteen years old, but within a few hours of hearing her play, I had an epiphany,’ recalled Giercke. ‘Not only did she have a great feeling for Johann Sebastian Bach and the Germany of the seventeenth century, for Bach’s religious devotion and suffering, but she could evoke emotions and memories going back to my East German childhood in Magdeburg and Leipzig. She could play all the key piano pieces of the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries. She could play them by heart, never needing a written score. Mozart, Beethoven, Handel, Mendelssohn, Chopin, Liszt, Schumann, Rachmaninoff, Tchaikovsky, Scriabin. I’d never heard talent like it.’

With Giercke’s help and others’, Odgerel studied for nine years at a conservatory in Perugia in Italy. By the time I met her, her playing was sublime. The old instrument was gone, and she gave recitals on Giercke’s Yamaha baby grand, followed by dinners of roasted goat, each animal cooked from the inside out with a bellyful of hot rocks. Outside the ger’s wooden door was a wide plateau cupped by mountains, the steppe’s velvet folds studded with tombs and ancient standing stones left by successive waves of nomadic people. Yaks and horses, more numerous than people in Mongolia, grazed on the riverbank below. Inside the tent, the gathering included a Sherpa cook, a local shaman nicknamed The Bonesetter, and Tsogt, a Paris-trained opera singer from Inner Mongolia who was also a consummate archer. The baritone’s neck was always crooked from trying to fit into the ger’s low opening to listen to the piano concerts, the music’s deep, poignant conflicts floating up through an opening in the roof fashioned from a spoked wheel of painted wood.

One night, Giercke shook his head with irritation. The piano was a modern Yamaha, and out of sorts. It played with an even temper, but in his opinion, the sound wasn’t up to what it was before. Perhaps the steppe’s dry climate had finally caused it damage. Perhaps Odgerel’s tuner needed to return sooner than planned. Giercke leaned over and whispered in my ear his frustration, ‘We must find her one of the lost pianos of Siberia!’

That evening, he handed me a novel by an American author, Daniel Mason, about a British piano tuner who travelled up the Salween River into a lawless nineteenth-century Burma. The tuner was tasked to fix a rare 1840 grand piano belonging to an enigmatic army surgeon employed by the British War Office. The Erard functioned as a symbol of European nineteenth-century colonization in Asia, with many of the book’s themes recalling Joseph Conrad’s story of Kurtz, the painter, musician and ivory hunter who ‘goes native’ in Heart of Darkness. In Mason’s book, whenever the Erard was played, the music brought peace to the warring tribes. Giercke, who had a little bit of Kurtz to him, liked the idea of living ‘upriver’ with a spectacular piano; he saw no reason for a good piano hunt to be cast as fiction, nor to doubt there being pianos in Siberia in the first place: ‘If you, Sophy, would find a piano and bring it here, our story would be real.’ Giercke was a filmmaker and well travelled in Central Asia. He knew enough about the region’s history to believe that there would be instruments out there. He liked the idea of a piano bringing joy to his adopted country, and Odgerel having an instrument of her own – playing it in the Orkhon Valley in summer, and at her home in Ulaanbaatar in winter.

Through that dusty Mongolian summer, Odgerel and I became friends. We talked about her childhood, how her father was a basketball coach and her mother a gymnast. Odgerel’s family were Buryats, an indigenous group with strong Buddhist and shamanistic roots from close to Lake Baikal. In the thirties, members of her family were persecuted under Stalin, when nomadic pastoralism was replaced with collective herds, their Buddhist religion was suppressed, monasteries closed, their intelligentsia killed, and their homeland – defended in a 1929 rebellion that saw some thirty-five thousand Buryats killed – cut up into smaller territories. Some of Odgerel’s relatives fled to Mongolia.

While Odgerel’s story stayed with me, it was her music which moved me. The more I listened to her play, the more I wondered how an historic piano would sound different in the steppe – an instrument which still resonated with the gentler timbre of the nineteenth century: the moody nocturnes of John Field, the sparkling elegance of Chopin’s Ballades, the earthy texture of Tchaikovsky’s ‘Russian Rustic Scene’.* You don’t need a thundering concert piano in a space as intimate as a Mongolian ger. An interesting European instrument with a mellow voice would duet well with the plaintive morin khuur, the Mongolian horsehead fiddle. The combination was something Odgerel was also beginning to champion as a unique Eurasian style.

Odgerel Sampilnorov’s family. Her Buryat ancestors, originally from near Lake Baikal in Siberia, are pictured in the first image.

We talked a little about the difficulties that might lie ahead, and our mixed motivations. If I were to go and look in Siberia, I would need to understand the story of pianos in Russian culture and how and why these instruments had travelled east in the first place. I love nothing more than listening to people talk, whether in the pages of books, or across a table sharing a meal. Odgerel loves music; she wanted a piano with good sound. Giercke loves all of these things too, but above all, the spirit of adventure. Offering to help pay for the endeavour, he said that only in trying to take on something difficult would something interesting ever happen.

‘We made our plans in this way: If we could do it, it would be good, and a good story. And if we couldn’t do it, we would have a story, too, the story of not being able to do it.’ This is how John Steinbeck described his trip to the USSR in the aftermath of the Second World War with the photographer Robert Capa. Steinbeck’s approach appealed to me. So did Anton Chekhov’s, who declared his intention to travel across Siberia in a letter to his publisher in 1890: ‘Even assuming my excursion is an utter triviality, a piece of obstinacy and caprice, yet just you consider and then tell me what I’m losing by going. Time? Money? Will I undergo hardships? My time costs nothing. I never have any money anyway.’ In a fug of piano music, Mongolian vodka and late nights talking under a starry sky, a trip to Siberia sounded almost implausibly exciting. Then summer turned to autumn, and back home in England my mood darkened with the leaves and the seasonal malaise. I moved on from the idea of undertaking any Siberian piano hunt until eight months later, when I flew to the Russian Far East. Only when I started travelling deep into the Russian forest did I realize I could no more unsnag the idea of Siberia’s lost pianos than set out coatless into cold so extreme it makes your tears freeze into the lines around your eyes.

________________

* The clock can still be found encased in a protective glass box in the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg. The birds lie still for most of the week, but every so often their two-hundred-year-old mechanisms are carefully wound to give visitors a glimpse of the performance that captivated the Empress.

* ‘It is thought that by the end of her reign well over half the population of the Russian Empire had become a slave class, every bit as subjugated as the Negro slaves of America.’ A. N. Wilson, Tolstoy (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1988).

* ‘Polish’ is a simplification of the cultural nuances of the time, but is generally used to discuss the various ethnicities – Polish, Lithuanian, Belarusian, among others – sharing a region on Russia’s western edge with constantly shifting borders during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

* Confusingly, most non-Russian readers will know this as ‘the Eastern Front’, where the Allies fought Germany for control of Eastern Europe. For the Soviet Union, however, this was most definitely a Western Front. The Soviets’ Eastern Front centred around the invasion of Japanese-held Manchuria in 1945.

* Dumka, op. 59.