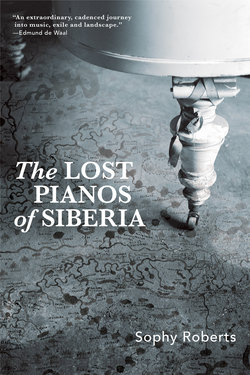

Читать книгу The Lost Pianos of Siberia - Sophy Roberts - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

The Paris of Siberia: Irkutsk

IN THE RUSSIAN STATE NAVAL ARCHIVES in St Petersburg, there is a revealing set of customs papers documenting the travails of a little clavichord – the earliest known record of such an instrument making it across Siberia. It belonged to a socially ambitious naval wife called Anna Bering who, in the 1730s, took this precious instrument from St Petersburg to the Sea of Okhotsk, and then travelled another six thousand miles home again on a magnificent transcontinental journey of exploration using only sleighs, boats and horses. Anna was married to Vitus Bering, a Danish-born sea captain in the service of Peter the Great. Known as the ‘Russian Columbus’, Bering’s job was to establish a postal route across Siberia, build ships on Russia’s Pacific coast, and then penetrate the American Northwest. Anna, along with her clavichord, accompanied him.

If the scale of Siberia is dumbfounding, it is even more so when the map is traced with instruments like Anna’s, which wove their way across the Empire before reasonable means of travel existed. They journeyed along Siberia’s expanding trade routes, usually setting off in the dead of winter when the ground was good for sledges, rather than in summer, when Siberia turned into a mire of mud covered with mosquitoes. Siberia’s rivers were another hindrance for travellers: instead of winding across the Empire from west to east, or vice versa, all the big waterways flowed south to north before emptying into a frozen Arctic Ocean.

Overland travel became easier when the Great Siberian Trakt opened during the reign of Catherine the Great. This was the main post road that ran from the brink of Siberia in the Ural Mountains to the city of Irkutsk, located close to Lake Baikal. The journey was infamous – a bumpy highway covered with slack beams of wood. The discomfort of traversing the road’s length by sledge recalled the sensation of a finger being dragged across all the keys of a piano, even the black notes, remarked a nineteenth-century Russian prince, who served as an officer in Siberia. ‘It is heavy going, very heavy,’ observed Anton Chekhov in 1890, ‘but it grows still heavier when you consider that this hideous, pock-marked strip of land, this foul smallpox of a road, is almost the sole artery linking Europe and Siberia! And we are told that along an artery like this civilisation is flowing into Siberia!’

Various methods available for travelling on ice in Siberia, according to the Jesuit explorer Father Philippe Avril in his 1692 work, Voyage en divers états d’Europe et d’Asie.

Chekhov had considered himself well prepared for his journey from Moscow through Siberia to reach the Tsarist penal colony of Sakhalin Island in the Russian Pacific, where he wrote an important piece of journalism about the brutality of the exile system. His mistake was the choice of season. Chekhov undertook his Siberian travels in spring – during rasputitsa, an evocative Russian word, as sticky as clods of earth, used to describe the muddy conditions that come with the thaw. He used a tarantass, a horse-drawn carriage with a half-hood, no springs, and wheels that could be interchanged for runners for the ice. Chekhov packed big boots, a sheepskin jacket, and an army officer’s waterproof leather coat, as well as a large knife – for hunting tigers, he joked. ‘I’m armed from head to foot,’ he wrote to his publisher. He passed chain gangs of convicts. The company he kept was poor. The coachmen were wolves. The women, who couldn’t sing, were colourless, cold and ‘coarse to the touch’. Inevitably, he got stuck in the seasonal mud, his tarantass caught like a fly in gooey jam.

The tarantass – depicted here crossing a tributary of Lake Baikal – was described by an English traveller in Russia in 1804 as a ‘wooden Machine precisely like a Cradle where People place their Beds and Sleep thro’ the entire of a Winter Journey’. The Russian Journals of Martha and Catherine Wilmot (London: Macmillan and Co., 1935).

Travellers put up with the unpleasantness because until the Trans-Siberian Railway arrived at the end of the nineteenth century, the Great Siberian Trakt was the only significant road nourishing Siberia with new blood from European Russia – or at least what had survived the journey over Western Siberia’s malarial Baraba Steppe. As for the lures of Irkutsk, they might not have been quite on a par with St Petersburg – everything in Siberia ran a hundred years behind the rest of Russia, noted an early visitor – but its relative cosmopolitanism provided some relief for travellers. When Chekhov visited, he remarked that Siberia was a place you rarely heard an accordion, blaming the lack of art and music on a pitiless struggle with nature, as if survival and culture were mutually exclusive. But Irkutsk, known as the Paris of Siberia, was an exception. Chekhov thought it ‘a splendid town’ lively with music and theatre, as well as ‘hellishly expensive’, with a very good patisserie.

Irkutsk was sophisticated for the provinces, an upwardly mobile town where it was important to the educated classes to grasp any threads of connection with European culture, which Catherine’s reign had encouraged. In 1782, the Imperial Academy of Sciences in St Petersburg despatched thirteen hundred books to Irkutsk. A public library went up, designed according to the fashionable European Russian style prevalent in the capital. An orchestra was founded, and a school teaching no less than five foreign languages. By the time of Catherine’s death in 1796, Irkutsk had turned into a critical junction of the two main trans-Siberian routes.

The southern route out of Irkutsk wound east over Lake Baikal, the water traversed either by sledge in winter or by ferry in summer. The road then spurred down towards the dusty Russia–China border town of Kiakhta, a famous staging post on the Eurasian tea route. The north-easterly passage from Irkutsk to Siberia’s Pacific rim was more forbidding: a thirty-day winter journey by dog-sled, reindeer-sled and horse-drawn cart east along the Yakutsk–Okhotsk Trakt to reach the shipbuilding yard of Okhotsk. One fifth of all the silk reaching Western Europe passed through Irkutsk, along with rhubarb – a precious commodity thought to be a miracle cure for a myriad of maladies – and a large share of China’s tea. For anyone of influence travelling across the Russian Empire, Irkutsk was an economic and geopolitical crucible in the heart of Eurasia – a significance symbolized by the elegant belfry at the top of the Church of the Raising of the Cross still dominating a small hill at the city centre where Arthur Psariov, a veteran of the Soviet–Afghan War,* has been ringing the church bells for the last three decades.

We had met the first winter of my search when Arthur led me through the nave, passing a tall priest with the poise of a chess piece, his neck held stiff in a rigid golden cassock. Incense drifted across the altar from a swinging ball and chain, the ball’s to-and-fro setting the measured pace of the priest’s holy incantations. Inside the bell tower, Arthur knew where the stairs’ rungs were weak, the wood spongy, the old nails unreliable with rust. When he skipped a step, I did the same, placing my feet into the crinkled prints he left in the thin membrane of frost that coated the tower’s throat, each staging post in the plexus of narrow steps more treacherous than the next.

At the top of the bell tower, its sides open to the weather, the snow absorbed the babble of the divine service going on downstairs: the priest chanting, babushki arriving with their trolley bags of shopping, the clunk and burst of heavy doors. The octagonal platform was topped with a stone cupola, its underbelly webbed with struts, many of them in poor repair. Circling the belfry was a balcony, its rim beaded in ice. Arthur warned me not to stand too close to the edge. Three of the wooden balusters were missing. Others were barely holding their place, hanging like loose teeth.

Beneath me lay the city’s wide boulevards. On a shallow incline stood historic wooden houses, and a few other bell towers puncturing the sky, their cupolas skinned in green, gold and peacock blue. With snow unable to stick to their pitch, the domes caught the sun, their satisfying shapes exactly as the author Jules Verne described them, like pot-bellied Chinese jars.

I looked for the train track to orientate me, and the river which runs through Irkutsk, winter’s grip holding it in frigid stasis. In the stillness, two figures in black moved through the whiteness below. One man shovelled snow from the cemetery path. Another swept up behind him, clearing the graves. I looked at them and wondered how they came to be there. Was the one with the dragging leg descended from a murderer, a tea trader, a political exile or a free settler? Or were they Old Siberians, born of the earliest Russian peasants, who intermarried with the indigenes? The pull of private histories is always present in Siberia. Every face informs the enigmatic texture of a place where the legacy of exile lingers, like the smell of incense, or the feeble gleam of traffic lights, with the complexity of Russia’s identity, and the mix of Europe and Asia, evident not just in the jumbled architecture of the Siberian baroque church I stood on top of in a snow-breeze in winter, but in the routes reaching out from every side.

Arthur guided me by the elbow to the edge of the belfry. He wanted to show me the nineteenth-century bell, which had been made in Berlin. The other bells came from the foundry towns ribboning the River Volga – a thousand-year-old tradition of Russian bell-making which had been significantly disrupted by the twentieth century’s atheist Soviet regime. In Irkutsk, the Soviets had turned the oldest church, into a cobbler’s shop, and another into a film studio. Bogoyavlensky Cathedral was used as a bakery, and the bell tower to store salt. These were fates to be preferred over that suffered by Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. Though now rebuilt, it was torn down under Stalin’s orders and turned into Russia’s largest open-air swimming pool.

Arthur started to play – softly at first, the resonance making the snow tremble on the belfry’s flimsy balustrade as the bell’s tongue licked its copper skirt. Then the patterns started to build until all eight bells were singing. Arthur pushed and pulled the ropes with his hands, while his feet worked pedals to strike the largest bells, the pace an exhilarating distillation of music’s power, of chords at once melodically familiar and outlandishly foreign.

For five or six minutes Arthur held the city in thrall, sweat riding down the sides of his temples, his body moving with the ease of a dancer, not a giant of a man in clumsy shoes. The sequences quickened until the deepest bell tolled three bass notes. With the sound eddying over Irkutsk, I imagined the townspeople looking up. Would they ever know the identity of this person who found such intense pleasure in such an improbable place? When the last note began to fade, Arthur turned around to face me, wiping his brow.

‘I can play most things, except rock ’n’ roll,’ he said, a broad smile reaching across his face.

*

In 1591, a bell was among the first exiles to Siberia – the weight of a horse, cut down from the belfry in Uglich, a town on a bend in the River Volga in European Russia. The bell had committed the crime of being tolled as a rallying call to urge the citizens to join a small, bold and foolhardy uprising against the state. In response, and to establish his legitimacy, the Tsar Regent executed two hundred of the Uglich townspeople. In a final sadistic twist, those exiled to Siberia were forced to carry the Uglich bell, itself subject to a public lashing, some thirteen hundred miles across the Ural Mountains to Tobolsk. Like the men who bore the instrument on its journey, who had their tongues cut out, the bell was also rendered mute by having its clapper removed. It was a terrifying symbolic act: by silencing music in the belfry, the regime was exerting the alarming reach of its power over every facet of Russian life.

Nor did the horror abate after the Revolution, when the Tsarist exile system was effectively relaunched as the Soviet Gulag. Victims travelled in cattle wagons on the railways to Siberia’s mines and ports. Kolyma-bound prisoners would then sail by Stalin’s convict ships into some of the darkest corners of Soviet Russia, populating the regime’s network of forced-labour camps with political opponents and urkas (prison slang for legitimate thieves, murderers and criminals).

For some, the experience was made bearable with the smallest of survival strategies. Fyodor Dostoevsky – who endured four years as a convict in Siberia, living with dripping ceilings, rotten floors, filth an inch thick, and convicts packed like herrings in a barrel – was given a copy of the New Testament by an exile’s wife, and taught a fellow prisoner to read. The tiger conservationist Aleksandr Batalov spoke about a friend who spent decades in a Stalinist labour camp; he said his friend’s study of the migrating birds around the camp was the thing that stopped him going crazy. Varlam Shalamov, a poet who spent a total of seventeen years in the Soviet Gulag, found no such comfort. He wrote about the terror of indifference, how the cold that froze a man’s spit could also freeze the soul.

I came to Irkutsk in pursuit of a piano which represented the opposite of Shalamov’s tears: the instrument belonging to Maria Volkonsky, the wife of one of the nineteenth century’s most high-profile political exiles. It functioned like a fulcrum in Siberia’s piano history, marking the moment when classical music in this penal wasteland was invested with a keen sense of European identity and pride, the piano’s Siberian story beginning with a poorly conceived rebellion in St Petersburg on 14 December 1825. It was the day of the winter solstice – an event traditionally bound to all sorts of ideas about birth, death and change.

An official NKVD (secret police) photograph of Varlam Shalamov following his January 1937 arrest for ‘counter-revolutionary’ activities.

Before dawn was up, a group of men gathered in the city’s Senate Square with the intention of deposing the Tsarist regime. The Decembrists, as the rebels came to be known, comprised noblemen, gentlemen and soldiers – including Maria Volkonsky’s husband, Sergei. Having fought alongside the peasantry during the Napoleonic Wars, Russia’s elite had come to admire the stoicism of their fellow countrymen. Liberal idealists all, the Decembrists not only wanted emancipation for Russia’s beleaguered serfs; they also sought to replace the country’s political structure with a constitutional monarchy, or even a republican form of government – a response to the despotism of the Romanovs, which had defined the dynasty’s long lineage since 1613.

Dissent had stepped up after Catherine the Great’s death. Her son, Tsar Paul I, had enjoyed a brief, tyrannical tenure before assassins strangled him with a sash in 1801. Paul’s murder was probably a good thing for music. Suspicious of Western thought to the point of paranoia, Paul formalized a ruthless backlash to Catherine’s flirtations with the Enlightenment. He banned any kind of foreign-printed book or pamphlet from entering Russia, including sheet music.

The next in line, Tsar Alexander I, had a reformer’s spirit. He relaxed state censorship but failed to progress emancipation in any meaningful way. After the trauma of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812, when Moscow was all but burnt to the ground, Alexander governed with almost schizophrenic swings. He tried to improve the exile system, introducing new rights for convicts; he also fell under the influence of a demonic Russian general, Aleksei Arakcheyev, who was obsessed with turning the Empire into a military state. Alexander took increasingly draconian measures against liberal foreign influence. In 1823, he banned Russian students from entering certain German universities, lest they be exposed to seditious ideas.

When Alexander died childless in 1825, leaving the country in a state of bankruptcy, Alexander’s brothers hesitated to fill the throne. The Russian crown, gossiped contemporary chroniclers, was being passed around the family like a cup of tea nobody wanted to drink. Constantine, the elder of Alexander’s siblings, had already run off to Poland, where he had fallen in love with a Catholic pianist (after Constantine first heard the ten-year-old prodigy play, his wife often invited Chopin to their Polish residence, convinced his music calmed Constantine’s difficult nerves). Alexander’s youngest brother, Nicholas, was also slow to act and take up the vacant throne; he needed to be cautious lest any advances he made be considered a coup. For the Decembrist revolutionaries, this messy two-week interregnum therefore presented the perfect opportunity to advance their plans for revolt.

But while the Decembrists’ motives were impassioned, their regiments were not. When the men began to assemble in Senate Square, there was a smaller force of rebel soldiers than the Decembrists had hoped. In addition, one of the main leaders deserted. Despite these setbacks, the Decembrists refused to disperse, so Nicholas ordered a cavalry squad to break up the rabble. Only with the whine of cannon fire did the men eventually retreat to a frozen River Neva, where Nicholas’s soldiers blitzed the ice with artillery. By nightfall, the revolt was quashed. The perpetrators were rounded up. On the same day as the Decembrist Revolt, also referred to as the First Russian Revolution, Nicholas I declared himself Tsar.

Close to six hundred suspects were put on trial. Five men were hanged, including the poet and publisher Kondraty Ryleev, who was executed holding a book by Byron in his hand. When the rope snapped on the first attempt, one of the prisoners reportedly quipped: ‘What a wretched country! They don’t even know how to hang properly.’ Another of the condemned men remarked on the privilege of dying not once but twice for his country. Whether any of these remarks are true is beside the point: the myth of the Decembrists’ martyrdom took root when Tsar Nicholas I ordered the execution to continue, and the gallows were strung with new rope.

With the hangings complete, a core of more than a hundred men were identified as coup leaders and sent to Siberia for hard labour, some for life.* They were stripped of their wealth and privileges. As they were members of some of the grandest, most decorated families in Russia, this was the high-society scandal of the time. It was talked about all over Europe, with the vengeance in Nicholas’s response also changing Russians’ perception of banishment forever. Prior to 1825, very little compassion had existed for the men, women and children sent to Siberia. After 1825, political exiles were regarded with far greater sympathy. As for the eleven women who elected to follow their Decembrist husbands and lovers into exile, they were revered as living saints. Under the rules of banishment, the women had to leave their children behind in European Russia. Any offspring conceived in exile would be forbidden from inheriting their family’s titles or estates.

The five Decembrists hanging from the gallows, sketched in Pushkin’s notepad. Pushkin was closely linked to the revolt, having gone to school with some leading Decembrists. His 1817 poem ‘Ode to Liberty’ was also cited by some conspirators as an influence. As a result, Pushkin was brought before the Tsar and restrictions placed on his freedom of movement and expression.

One of the most high-profile Decembrists banished for life was Prince Sergei Volkonsky – a childhood playmate of the Tsar’s, whose mother was a principal lady-in-waiting to the Dowager Empress. Sergei’s wife, Maria, came from an equally elite family. Her father, General Raevsky, was one of the heroes of Napoleon’s defeat in 1812. With her knowledge of literature, music and foreign languages, Maria was a descendant of Catherine’s ‘Enlightened’ Russia. She was also a well-known beauty, her abundant black curls and olive skin earning her the nickname la fille du Ganges.*

Maria decided to abandon her enchanted circle – as well as her infant son, who would die aged two – and follow her husband into exile. It became one of the most talked about tragedies of a feverishly romantic century. ‘All her life was this one unconscious weaving of invisible roses in the lives of those with whom she came in contact’ is how Tolstoy described the heroine, modelled on Maria, in his unfinished mid-nineteenth-century novel The Decembrists. Maria’s actions inspired paintings, music and Pushkin’s poetry, as well as a love of the piano on the other side of the Urals, when she took a clavichord some four thousand miles from Moscow to join her husband deep in the Siberian taiga.

The instrument, kept close at hand throughout Maria’s exile, was a gift from her sister-in-law Zinaida Volkonsky – a keen patron of the virtuosos, who hosted one of the most well-regarded cultural salons of the period. When Zinaida threw a leaving party in Moscow on the eve of Maria’s Siberian journey, Maria sat close to Zinaida’s piano, and Pushkin close to Maria. She wanted her friends to sing so that she wouldn’t forget their voices in exile. Shortly afterwards, she set off for Siberia with the clavichord Zinaida had strapped to her sledge. It was a remarkable journey, the instrument travelling all the way from Moscow to the eastern side of Lake Baikal. What the local Buryats would have made of this Russian princess as they watched her passage across the lake is hard to picture. The Buryats thought the Milky Way was ‘a stitched seam’, and the stars the holes in the sky. When meteors flashed, Siberia’s indigenous tribes described it as the gods peeling back ‘the sky-cover to see what is happening on Earth’. The sight of Maria bundled up in her ermine furs must have appeared out of this world to them, like a visitation from another planet.

Maria spent her first few months in exile in the town of Nerchinsk, near the Mongolian border, living in a small Cossack hut. She was allowed to visit Sergei’s cell twice a week. At first the men were forbidden to receive packages from relatives in European Russia, so the women began to sneak money into Siberia through secret channels in order to buy the prisoners extra privileges. When a French-born couturier arrived in Nerchinsk in pursuit of her Decembrist lover, she turned up with hundreds of roubles stitched into her clothes. She also smuggled in Italian sheet music for Maria. The women were pushy, persistent and resourceful. As for the Decembrists’ prison commander, he soon got the measure of their capabilities, remarking ‘he would rather deal with a hundred political exiles than a dozen of their wives’.

The men were moved a year later to a prison at Chita, also east of Lake Baikal. Later, the Decembrists were transferred to a new jail at Petrovsky Zavod, in a nearby valley, where the wives were allowed to share their husband’s room. Maria’s clavichord moved into the windowless prison, which was far gloomier than the one at Chita. As the years went by, children were conceived. Maria learned to speak Russian, as opposed to the French of her aristocratic childhood. She gave birth to a little girl, who died after only two days. Her next two children, a son and a daughter, survived.*

While family provided comfort to a few of the Decembrists, it was through culture – for many, music in particular – that they were able to maintain some kind of connection to the lives they had left behind, helped along by relatives sending books, paints and large sums of money from home. ‘What remarkable fighters they were, what personalities, what people!’ wrote the nineteenth-century Russian journalist Alexander Herzen of the gentlemen revolutionaries. The Decembrists represented everything brave and humane that was missing from Tsar Nicholas I’s lightless reign. ‘I have been told, – I don’t know whether it is true, – that wherever they worked in the mines in Siberia, or whatever it is called, the convicts who were with them, improved in their presence,’ wrote Tolstoy.

The Decembrists teamed up to create a small academy in exile. They set up carpentry, blacksmith and bookbinding workshops, and ran lectures on subjects from seamanship to anatomy, physics to fiscal theory. They established a library, which they filled with thousands of books sent by their relatives (according to one account, a collection that numbered nearly half a million). Another building was turned into a music room for piano, flute and strings. Locals came to study, and to attend the Decembrists’ concerts and musical soirées. The prisoners dreamed up imaginary lands, inventing sea stories about the distant oceans, and found comfort in the smallest delights of nature. The Borisov brothers, for instance, went on to build a huge Siberian insect collection. Meanwhile, the school the Decembrists created during their prison years benefitted hundreds of Siberian peasant children.

An 1832 drawing by fellow Decembrist Nikolai Bestuzhev of the Volkonskys in their cell at Petrovsky Zavod.

When Sergei Volkonsky’s decade-long hard-labour sentence was up, the Volkonskys had greater freedom to influence Siberian culture, specifically in and around Irkutsk, where they were required to settle in exile. The Volkonskys were allocated a plot in swampy taiga. This was when Maria’s two surviving children learned the native Siberian dialect. Then, in 1844, the Volkonskys bought a house in town.

The Volkonskys’ manor house in Irkutsk.

Year by year, Maria gained confidence under a sympathetic new governor, who became a visitor to her musical salons. She expanded Irkutsk’s hospital for orphans, fought for musical education to be introduced in schools, and raised money to build the town’s first purpose-built concert hall – civic duties that earned her the sobriquet ‘the Princess of Siberia’. When a classical pianist from Tobolsk came to play in Irkutsk, Maria broke protocol for an exile’s wife: she went to the concert, and was given a standing ovation. Sergei led a humbler life; he grew a long beard and frequented the market with a goose under his arm. Nicknamed ‘the peasant prince’, he was simple and unostentatious, deeply respected by Siberians who sought his help. He made numerous friends among the locals, with whom he shared his knowledge of agriculture and strand of liberal political philosophy. Meanwhile, elsewhere in Europe, Sergei’s lifelong quest for fairer government looked like it might be coming of age. During the 1848 Spring of Nations, absolutist regimes were toppling and a reformist press was on the rise. Prussian liberals got their constitution, and elective assemblies. In Hungary, serfdom was finally outlawed.

When I visited the Volkonskys’ two-storey house in Irkutsk, now a museum, frost laced the panes and dulled the glow of lamps inside. Upstairs there was a pyramid piano – an instrument of peculiar shape and height, like a concert piano turned up against the wall. The museum staff said it probably belonged to the family’s Florentine music teacher, who had lived in one of the outbuildings. Downstairs, there was a beautiful Russian-made Lichtenthal, which Maria’s brother delivered from St Petersburg. The Lichtenthal, made by a piano maker who had moved to Russia following the Belgian revolution of 1830, was the grandest instrument Maria owned. It was also the most potent surviving symbol of her affection for music, given that Maria’s original clavichord, which had travelled on her sledge from Moscow to Siberia, had disappeared – when or where, no one was quite sure.

As for the Lichtenthal, the instrument behaved awkwardly when a museum worker tried to make the prop stick hold up the lid. The keys were sticky, like an old typewriter gluey with ink. He struck the keys until the softened notes – muted by a layer of dust, perhaps, or felt that had swollen in the damp – started to appear. At first the sound was reed-thin, no louder than the flick of a fingernail on a bell. Inside the piano, the amber wood still gleamed, the strings’ fragile tensions held in place by tiny twists around the heads of golden, round-headed tuning pins. The Lichtenthal, said the museum worker, was full of moods that made it challenging to tune. In Siberia, violent swings in humidity and heat can shrink the wood. The soundboard, a large, thin piece of wood which transforms vibrations into musical tones, can easily crack. Different makers devised different solutions to this problem. Mozart’s favourite maker would deliberately split a piano’s soundboard by exposing it to rain and sun, and would then wedge and glue it back together so that it might never break again.

I traced the Lichtenthal’s restorer who had picked the yellowed ivory tops off the keys to clean them, re-spun the bass strings, and repaired the veneer.* I also wanted to talk to the piano’s current keepers, to see whether they might know of other noble instruments of its type. One thing led to another and via various other city institutions, I was connected with an Irkutsk piano tuner who seemed to hold the keys to my quest. Cutting an elegant figure with a tuning hammer in his leather satchel, he said he had a private collection of forty historic instruments. His most prized piano was a rare 1813 grand which he had bought for a few kopeks from an army general in the early nineties. It was an Andreas Marschall, serial number 5, traced back to a very old Danish maker. He said it was in such bad condition that it was just a box and strings, but one day he wanted to do it up.

I made an appointment to visit the tuner’s Siberian workshop a few months later, but when I arrived back in Irkutsk, he didn’t show up as we had agreed. When I found the numbers of other tuners working in Irkutsk, they seemed reluctant to talk. Feeling the cold of being an outsider in Siberia, I eventually persuaded one of them to act as my paid guide. We drove out to a small apartment, where he was restoring a Bechstein grand. He said it originally belonged to a local cultural activist who had brought the piano to Irkutsk from Moscow in the thirties. The piano was broken up into all its parts with the soundboard laid out like an old drunk waiting to die. It was positioned in front of an electric fire to help dry it out, the keys and strings a jumble on the floor. One day he would finish the restoration, he said; there was a market for these grand pianos in Russia. He showed me another private instrument in his home: an upright Smidt & Wegener piano which he had reason to believe belonged to, or was played by, the wife of Mikhail Frunze, a Red Army commander in the Russian Civil War. The tuner opened the piano up to show me where he had found three gold coins, dated 1898, minted with the face of Tsar Nicholas II. The tuner had sold the coins during perestroika to help make ends meet.

I would find many more secrets like this, said a local musicologist: Siberia’s pianos were full of hidden treasures, like the grand piano her teacher used to own. Inside its workings, the woman had concealed all her jewellery. The piano was her teacher’s family safe. But she warned me I would also need to keep my wits about me, because there were all sorts of complications with proving provenance in Russia. I knew there would also be stories people wouldn’t want told. There was a risk that my research might reveal the original, rightful owner of an instrument, which could open up a cat’s cradle of restitution claims. There would be others who wouldn’t want to talk of the past – any part of it. ‘Some things I cannot speak of,’ said a piano expert I met in Western Siberia: ‘We envy countries which provide easy access to what happened to their families, but here it is different. Access to archives isn’t easy. It’s not open source. It’s expensive. My generation belongs to the war children. We lost one or two of our parents, and ever since have been seeking the truth.’ We all do what we can to keep on going, warned another tuner; stories shift to fit our needs. He said there are pianos with the serial number painted on to the soundboard, and then those with a number moulded into the cast-iron frame. You can repaint a soundboard, he said, but you can’t change a number cast in metal.

This was always going to be my biggest challenge – looking for reliable truth. I wasn’t after a fancy piece of furniture to show off in the equivalent of a Mongolian parlour. I couldn’t have cared less, in fact, how a piano looked. I wasn’t here to fiddle with serial numbers, or pursue old pianos painted up in glossy colours. Such an instrument would be ill matched to a musician like Odgerel, who needed pure sound reinforced by a retrievable inner story. Odgerel’s musical perception was so authentic, she could render J. S. Bach’s ‘Chaconne’* with an exceptional depth of feeling. She could communicate the composer’s unquestioning faith in the divine. More than anything, Odgerel understood how struggle can invest the act of musical creation with the conviction of felt experience.

‘Bach tells us about tragedy and pain in a musical language. Whenever I read about the triumph of the Resurrection I cannot feel very much, but when I play “Chaconne”,’ Odgerel told me, ‘the story comes alive. Bach taught me how to breathe.’

Was it the same for Maria Volkonsky? What did a piano mean to her in exile? Did Siberia allow her to live more intensely than she could have ever done in high society back home? Was it empowering in nineteenth-century Russia to be disconnected from the period’s suffocating rules and expectations around her gender and class? Because despite the privations of their exile, the Decembrists didn’t view Siberia as a place only of katorga. ‘The further we moved into Siberia, the more it improved in my sight,’ observed the Decembrist Nikolai Basargin: ‘To me, the common folk seemed freer, brighter, even better educated than our Russian peasantry – especially more so than our estate serfs. They better understood the dignity of man, and valued their rights more highly.’ Siberia, you see, never had a history of serfdom. There were the exiles who came as prisoners of the state, but there were also many, many more migrants who ventured into Siberia for the taste of freedom – to live far from the reach of the Tsar and the moral reprimands of the Russian Orthodox Church.

________________

* Fought from 1979 to 1989 in support of the Afghan communist government.

* Among the exceptions was Nikolai Turgenev (uncle to the novelist Ivan Turgenev), who was out of the country on the day of revolt, and never returned to face the Tsar’s ire.

* The phrase was Pushkin’s. He reportedly fell in love with Maria when she was barely out of her childhood during a holiday he took with her family in Crimea.

* The Volkonsky love story wasn’t perfect. Various historians suggest Maria’s two children were the progeny of her long affair with Sergei’s friend and fellow Decembrist the charismatic Alessandro Poggio, who ran the prisoners’ vegetable garden with Maria’s husband.

* Given its grand provenance, the Lichtenthal was sent from Irkutsk to St Petersburg for a major restoration in the nineties. The then museum director organized delivery of the instrument by military plane to a restorer called Yuri Borisov – a man I went to meet, dubbed ‘The Last of the Mohicans’, trained by one of the original pre-Revolution masters from the Becker factory.

* J. S. Bach’s ‘Chaconne’ was the final movement of his Partita No. 2 in D Minor, and was written for violin. Italian composer Ferruccio Busoni transcribed Bach’s music for the piano between 1891 and 1892.