Читать книгу The Lost Pianos of Siberia - Sophy Roberts - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

Pianos in a Sandy Venice: Kiakhta

IN 1856, WHEN MARIA VOLKONSKY made her last visit to Lake Baikal, she described watching the forest animals coming in to drink as if Siberia were a Garden of Eden rather than her prison for the last thirty years. She was leaving Siberia. The new Tsar, Alexander II, had granted amnesty to the twenty-odd surviving Decembrist rebels. Some of the men had already committed suicide before the amnesty came through. Others had lost their wits. One or two were trying to make their living through teaching, farming watermelons, making opticals, or even drawing butterflies for German museums. Among those who stayed on voluntarily after the amnesty was Mikhail Küchelbecker, who was shackled to Siberia by an unfulfilled love affair with a local girl. His headstone stands on the eastern shoreline of Lake Baikal.

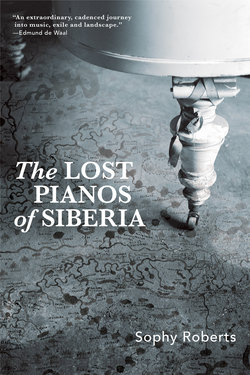

I spent almost three weeks poking around the lake, making three different visits. But however hard I wished it, Baikal’s seductive lures – the winter ice, the summer sward crackling with crickets, the red-barked cedar trees arcing out from cliffs – didn’t deliver on the piano discoveries I needed. The settlements were too thin. There was more for me in Kiakhta, the old tea traders’ town on the Mongolia–Russia border depicted by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels as if it were one of the most important centres of nineteenth-century world trade. In Kiakhta, I had been told about a rare Bechstein grand piano.

My tipster was the Mongolian opera singer, Tsogt, who used to stand at the door of the tent in the Orkhon Valley trying to fit into the narrow opening to listen to Odgerel play. He was a Buddhist and a Buryat whose ancestors, like Odgerel’s, had fled the Lake Baikal region in the thirties. His family ended up in Inner Mongolia, which is a part of China. He had trained in music in Beijing. He had also lived for a while in Ulan-Ude, the capital of Buryatia, one of the Russian Federation’s autonomous republics, and a half-day’s drive from Baikal’s eastern shore. A bear of a man, Tsogt wore leather boots designed with upturned toes so as to tread softly on the snow, and a traditional Mongolian felted del robe, belted below the waist, which made his belly look like a beer casket. We had travelled together across western Mongolia in 2001. Over the years, I had grown fond of Tsogt. I liked watching his tough front fall away in the presence of Bach. So I hired him early on to help look for pianos.

For a while, I heard nothing. Then I received a short and intriguing email: ‘I’m back from Siberia. I find only one grand piano. C. Bechstein – Serial number 7050. Year is 1874. From very little place. No other people has old piano.’

Given the Bechstein’s date, which was before a railway looped south beneath the lake, the piano may have taken a number of different routes. It could have travelled the rutted road running along the craggy south coast. It could also have crossed the lake by boat in summer, or by sledge in winter, or travelled on the Baikal, a British-built icebreaker. The ship, made of parts transported to Russia in pieces, sometimes took up to a week to make the winter crossing – from port to port, less than fifty miles – carrying twenty-five Trans-Siberian Railway cars on her specially designed deck. The carriages would be uncoupled at the water’s edge and shunted on to the ship’s on-board rails. In the depths of winter in 1904, when the ice was too thick for even the ship to break, a seasonal track was laid over Lake Baikal’s frozen surface instead. The first engine across plunged straight through the ice – a blank white canvas which these days is carved by the lonely movements of the few fishermen who still live along Baikal’s shores, the lake’s frozen surface scored with lines from snowmobile tracks and black dots where the fishermen have cut holes. The sweeps and curves look like the drawings of Wassily Kandinsky – an avant-garde, turn-of-the-century Russian artist obsessed by Russian ethnography, the ‘double faith’ combining paganism and Christianity, as well as the relationship between music and painting, between sound, points, lines and planes.

Wassily Kandinsky’s theory of music’s relationship to art, from his 1926 work, Point and Line to Plane.

Kandinsky’s great-grandmother claimed Buryat–Mongol blood. His father was a tea merchant from Kiakhta. One side of the Kandinsky family, who became fabulously rich over the course of the nineteenth century, were descended from church robbers and highwaymen, or so the story goes. Before Kandinsky’s time, when his relations were living in a taiga village east of Lake Baikal, the family were visited by Decembrists, including Sergei Volkonsky, who were entertained by the music from several pianos that the Kandinskys owned.

If the Kandinsky history gave Kiakhta a sprinkling of glamour, the snobbery of nineteenth-century travellers gave the town a rather different reputation. ‘There was not a lady without a large hat decorated with what looked like an entire flowerbed,’ remarked Elisabeth von Wrangell, wife of the governor of Russian America, who ridiculed the local merchants’ wives when she stopped by Kiakhta on her twelve-thousand-mile journey from St Petersburg to America. ‘The Russians, after all that they have borrowed from their western neighbours, remain barbarians at bottom,’ observed Alexander Michie, a Scotsman who tarried in Kiakhta on an 1863 passage through Siberia from Peking: ‘Their living in large houses, and drinking expensive wines, serve merely to exhibit, in more striking colours, the native barbarism of the stock on which these twigs of a higher order of life have been engrafted.’

I encountered a scene of complete decrepitude. Wooden homes tumbled out over a sandier landscape than I had so far got used to in Siberia. In this barren steppe country, the snow didn’t seem to settle like it did further north, but hung in the air like smoke. Kiakhta’s churches were largely windowless, sometimes steeple-less, and its roads so pitted it was sometimes easier to walk the streets than find a car. The once-grand façades of wooden houses were smeared with graffiti, and one of the cemeteries smelled of urine. There was a menacing stasis to both Kiakhta, where the merchants had their homes and trading houses in the nineteenth century, and Troitskosavsk, the adjacent settlement, which was once populated by the shops, schools and administrators. It felt as though the town was only just surviving, its edge of existence marked by a thin line of trucks lingering for a couple of lazy hours as they waited to cross the border between Russia and Mongolia.

Yet once Kiakhta had been so lively. During its pre-Revolution heyday, the town’s club put on balls and musical events. Concerts by European pianists visiting Kiakhta were advertised in Irkutsk, Tomsk and Chita. At one time in history, there were enough good pianos in town to justify a tuner travelling here all the way from Kiev.

A nineteenth-century account called the town Asia’s ‘Sandy Venice’. Tea caravans, loaded up on to camels, would arrive from Mongolia, looking like the merchants and their ships that once sailed into Italy’s great maritime capital. Up to a hundred horses filled the yard of a Kiakhta merchant’s home. Mansions shimmered with winter gardens. The merchants’ wives ordered their dresses from the Paris couturier The House of Worth, and filled their cellars with rare wines. The merchants also had summer cottages, or dachas, with bathing pools and a boating lake. The children were given donkeys with miniature carriages, and piano lessons from Polish political exiles. At Christmas-time, tables were loaded with champagne. Dressed in masks and festive costumes, the first families of Kiakhta would parade through town with a small orchestra and a local composer. The party would continue through the night to other merchants’ homes, where they danced quadrilles and waltzes.

The reason for this wealth was unique in Russia: for every consignment of tea that passed through this border, Kiakhta’s merchants creamed off a tidy local tax, part of which was invested in local philanthropy. It worked brilliantly until the money started to show signs of drying up after 1869, when the access provided by the Suez Canal took business from Eurasia’s camel trains. When the Trans-Siberian Railway was built many miles to the town’s north, Kiakhta’s relevance began to wane even further. By the first decade of the twentieth century, Siberia’s richest marketplace no longer teemed with Chinese, or crates of tea stacked in pyramids taller than the merchants’ homes. But Kiakhta was still very, very wealthy. Right up until the Revolution, it remained a place where pianos – like Kiakhta’s Bechstein grand, which Tsogt had found on my behalf – tinkled with mazurkas and other Polish dances. The Bechstein was thought to be connected to the Lushnikov merchant family, said the guide who showed me around the town’s splendid museum the first time I came.

I went to find the Lushnikov residence where the piano would have stood, close to Kiakhta’s Resurrection Cathedral, which once had columns made of crystal. On top of a small hill looking down on Mongolia, I found the house where the Lushnikovs hosted scientists and explorers, many of whom were stopping on their travels to Central Asia, whether looking for new species, or seeking out the holy secrets of Tibet. Kiakhta was also where Grigory Potanin buried his wife, the brilliant Russian explorer Aleksandra Potanina, who was among the first women to win a gold medal from the Imperial Russian Geographical Society. During her funeral, the Lushnikov house was overflowing with mourners. Her husband was among the nineteenth century’s most outspoken advocates for an independent Siberia and an end to the exile system. When the American journalist George Kennan stopped in Kiakhta in the 1880s on his epic journey across Siberia to report on the Tsarist exile system, he too visited the Lushnikovs’ home. ‘We were very often surprised in these far-away parts of the globe to find ourselves linked by so many persons and associations to the civilized world,’ remarked Kennan.

A late-nineteenth-century photograph of Aleksei Lushnikov, pictured with his wife, Klavdia, and their family at their country residence situated about twenty miles outside Kiakhta.

The Lushnikovs were in fact a powerful example of the Decembrists’ reach and influence, the family’s lives testament to an extraordinary moment in Siberian culture. The matriarch, Klavdia Lushnikov – a Kandinsky cousin – was educated in Irkutsk at the Institute of Noblewomen. Standing at the centre of the Kiakhta intelligentsia, she was a gifted pianist, nicknamed ‘Lushnikova the Liberal’, who became well known for her musical salons. Twice a week, she would gather the women for lectures on literature, politics and economics. She had married the millionaire tea trader Aleksei Lushnikov – a sophisticated man born into a modest family in the nearby Selenga Valley. Aleksei had been educated from the age of eight by Mikhail and Nikolai Bestuzhev, two Decembrists who had made an impressive job of exile by farming and teaching in the region after their hard-labour sentences were up. As for Aleksei Lushnikov’s children, one daughter studied sculpture with Rodin in Paris. Another daughter went on to sing at the Tbilisi Opera House.

The American journalist George Kennan pictured next to his Siberian tarantass, c. 1885.

Both Bestuzhevs were well qualified to act as teachers – Nikolai in particular, whose story is so full of charm and conviction. A musician, scientist and painter, Nikolai was responsible for most of the surviving portraits of his fellow Decembrists in Siberia. During exile, he relied on colour pigments sent by Maria Volkonsky’s sister-in-law Zinaida, who also posted seeds for the Decembrists’ vegetable garden. The gentle countenance in Nikolai’s self-portrait is hard to square with the image of a violent revolutionary who briefed the Tsar’s would-be assassin on the morning of the Decembrist Revolt. He made his journey to Siberia with a volume of the Rambler tucked into his luggage – an English periodical full of elevated prose and humanist ideas encouraging greater social mobility between classes.

While Nikolai tended to paint the Decembrists’ lives in rosier hues than their grubby reality, he still communicated the sorrow of exile with a moving depth. He drew his compatriots reading, talking, painting, often in lonely thought. He depicted their prison as if it were an English landscape, and the Decembrists’ children playing with kites. He also painted that famous image of Maria Volkonsky sitting with her narrow back to the artist in the Volkonskys’ cell, her right hand on the piano. The picture is a reminder of how fragile Beethoven must have sounded in this part of the world, rendered into quivering melodies on Maria’s clavichord – ghost sounds from the salons of Europe played on this weak and imperfect instrument, its parts fixed up by the convict with the so-called ‘golden fingers’. Nikolai was also an able engineer. He made hats, jewellery from the Decembrists’ old fetters (coveted by fashionable women in Kiakhta and Irkutsk as rings), cradles and coffins. He was an expert watchmaker. Many years after his release, Nikolai had finessed his chronometer designs developed in prison. He made a clock, which kept time at his house near Kiakhta: ‘In spite of a frost of twenty-five degrees, it went perfectly,’ said his fellow Decembrist Baron Rozen.

Aleksei Lushnikov’s daughters in the 1870s; the family pictured at a Russian-made Becker piano.

With the Bestuzhevs as his teachers, Aleksei Lushnikov therefore received one of the most unusual educations in nineteenth-century Siberia for a child of such modest roots. By the time he had entered the service of a Kiakhta merchant, Lushnikov could recite pages of Pushkin by heart. Once he had made his fortune, Lushnikov opened Kiakhta’s first printing house, and founded its first newspaper, the Kiakhta Page – one of many that flourished in the late nineteenth century when Siberia was developing lively journalism, its own universities and home-grown intelligentsia. Lushnikov subscribed to all sorts of politically progressive magazines and newspapers, including The Bell, printed in London by the émigré Alexander Herzen, who became Russia’s first independent political publisher. Although prohibited by the Tsarist government, The Bell was distributed to Siberia by the Kiakhta trading caravans, with Kiakhta’s merchants providing a safe house and funds to others in Herzen’s circle.

The democratic values which flowed out of Lushnikov’s home – like many of the Kiakhta merchants, Lushnikov contributed generously to the city’s library, museum, orphanage and schools – were sustained by the lifelong friendship the family kept up with both Bestuzhevs. Nikolai visited the Lushnikovs frequently to paint dozens of portraits of the Kiakhta elite. Before he died, he entrusted many of his paintings to Lushnikov, a collection lost in the post in the 1870s, according to one account. There was also a trunk Lushnikov asked nobody to open until twenty-five years after his death. He kept the key on a chain with a crucifix around his neck. Both the key and the trunk vanished, presumably in the chaos of the Russian Civil War.

That was why the Bechstein felt so remarkable, even if it was sad and weary, the piano’s bald hammers and loose strings barely able to produce a sound. Located in one of the museum’s cold corners, its bones were chilled from a draught that slunk in through the windows. I pressed for more information, with calls and a second visit to Kiakhta two years later. Locals helping me around town also spoke of the Lushnikov connection; that was how the story ran. One of the archivists, a woman who was new to me when I returned to Kiakhta, said she would make some further investigations. ‘I suspect it is a legend,’ she said after a while. ‘People say it is the Lushnikovs’, but these things are hard to prove.’

Before I left Kiakhta for the last time, I went back to the Lushnikov mansion. I walked around the back to try and peek through the windows. A man answered the door. He let me into the only room of the house still occupied.

On the ground floor, there was just enough room for a cooker and a bed, which the man shared with his four-year-old son. He couldn’t remember how long he had lived there, but it was from around the time that he got work helping Kiakhta’s Father Oleg clean up the church in the nineties. Back then, there had been another family living on the second floor of the house, but otherwise there hadn’t been anyone else he could recall for twenty-five years. The decaying wood was too dangerous; the roof had fallen in. As we talked, the dogs were circling again outside. In the stableyard, a man who had offered to help me fell to the ground in an epileptic fit.

On my last night in Kiakhta, I slipped into the back of the Trinity Cathedral – the town’s largest abandoned church, opposite the old trading houses – through a gap in some metal railings. The nave, missing its dome, looked like a skull that had been trepanned for a post-mortem. The masonry was loose, the ground tangled with undergrowth and broken glass.

I didn’t know what I had expected to find, especially in the dark, but as soon as I was beyond the cordon, it felt as if something bad had happened here, that I was walking unquiet earth. I had read about Kiakhta in the Russian Civil War, how the massacres were so brutal, the museum’s records of events were deliberately destroyed. When the enemy was approaching, the White Army killed some sixteen hundred Reds in Kiakhta in a cold-blooded orgy of bayonets and poison.

The tea millionaires scattered. Some of them were murdered, others fled to the Pacific ports via the Trans-Siberian trains. Kiakhta was in chaos, derived not only from the fallout of the Russian Civil War but from the Mongolian Revolution of 1921 just across the border. Leading the army of Mongol revolutionaries was a madman with an identity crisis: an Austrian-born German warlord – Baron von Ungern-Sternberg, known as the Bloody White Baron – who had originally attached himself to imperial Russia as a Tsarist officer, then ‘went rogue’. Believing he was an incarnation of Genghis Khan, von Ungern wanted to reinstate Mongolia’s old Buddhist theocracy. To achieve his goal, he enacted a reign of terror against the Bolsheviks, which eventually brought him back to the Russia–Mongolia border territory. In the Mongolian town abutting Kiakhta, a suspected ‘Red’ met his death in a baker’s oven. In Kiakhta, the Baron’s enemies were locked into a room, and cold water sprayed on to their naked bodies. They were frozen to death rather than shot, so as not to waste bullets, the Baron’s capacity for murder said to be so bottomless that he was constantly inventing new ways of killing. One of his methods of execution was to tie his victim to two trees bent to the ground, which, when released, split the body in two.

Baron von Ungern-Sternberg, photographed in Mongolia in the early 1920s.

The currents of history swirled among the cathedral ruins – the story about the Bestuzhev drawings which went missing in the post, the trunk full of Decembrist secrets, the merchants’ pianos the tuner from Kiev came to fix. If none of this had happened – no 1917 Revolution, no White Baron, no Russian Civil War – what would Kiakhta have become? Would Siberia have flourished differently? Would it have spun off and become its own independent state as Potanin had once advocated?

The Kiakhta Bechstein, photographed in the town’s museum in 2016.