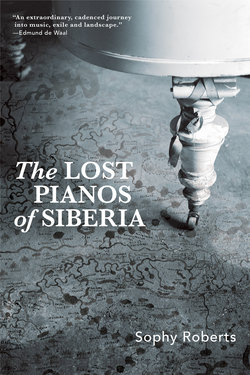

Читать книгу The Lost Pianos of Siberia - Sophy Roberts - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеAuthor’s Note

TRAVEL EAST BY TRAIN from Moscow and the clip of iron on track beats out the rhythm of your approach towards the Ural Mountains. This band of hills separates Western Russia from Siberia, rising in Kazakhstan and following an almost direct line up through Russia to the Arctic Ocean. The train passes lazy trails of chimney smoke, gilded churches, and layers of snow stacked like bolts of silk, with the rhythm of the journey – the sluggish gait, the grinding stops into gaunt platforms and huddled towns – much as early travellers described Russian trains in the fashionable Siberian railway sketches of the time. These days, however, fellow passengers are few; most Russians now fly to and from Siberia rather than use the railways.

During the time of the last Tsar, travellers on the country’s most iconic train of all – the train de luxe Sibérien, running for some five-and-a-half thousand miles from Moscow to Vladivostok on Russia’s Pacific coast – described an ebullient opulence, with passengers dripping in ‘diamonds that made one’s eyes ache’, and music from a Bechstein piano. Siberia’s railway was dizzy with ambition: ‘From the shores of the Pacific and the heights of the Himalayas, Russia will not only dominate the affairs of Asia but Europe as well,’ declared Sergei Witte, the statesman and engineer responsible for building the track at the end of the nineteenth century. In the fancy tourist carriages, there was a busy restaurant panelled in mahogany, and a Chinese-style smoking lounge, the train presided over by a heavily perfumed fat conductor with a pink silk handkerchief. French-speaking waiters came and went with Crimean clarets and beluga caviar, pushing through carriages decorated with mirrored walls and frescoes, a library, a darkroom for passengers to process camera film, and according to adverts promoting Siberia to tourists, a hairdressing salon, and a gym equipped with a rudimentary exercise bike. Singsongs tumbled out of the dining car as if it were a music hall, with the piano used like a kitchen sideboard to stack the dirty dishes on.

At no point on this great Eurasian railway journey, then or now, was there a sign saying ‘Welcome to Siberia’. There was only the dark smudge bestowed by cartographers denoting the Ural Mountains – a line that conjures up something vaguely monumental. In reality, the Urals feel closer to a kind of topographical humph, as if the land is somehow bored, the mountains showing as bumps and knuckles and straggling knolls. There is no dramatic curtain-raiser to the edge of Siberia, no meaningful brink to a specific place, just thick weather hanging over an abstract idea.

Siberia is difficult to pin down, its loose boundaries allowing each visitor to make of it whatever shape they want. In a drive for simplicity to organize these indistinct frontiers, I have therefore provided a few notes to explain my parameters.

The breadth of Russia has been squashed and squeezed into chapter maps in a struggle to fit this vast territory on to a single page. What makes it even more challenging is that aside from China, this country has more international borders than any other nation. In this Author’s Note I also give explanations about the time periods and terminology, which can get complicated in Russia. If my definitions are in any way reductive, it is because I am not a historian. If they are Eurocentric, it is because I am English; any journey to Siberia is one I take from the West to the East – physically, culturally, musically. This book – written for the general reader, about a hunt that is sometimes more about the looking than the finding in the so-called ‘land of endless talk’ – is a personal, literary adventure. More nuanced scholarly research and further reading is indicated in the Source Notes and Selected Bibliography.

My Siberia covers all the territory east of the Ural Mountains as far as the Pacific, which is the ‘Siberia’ defined on imperial Russian maps up until the Soviet period. It is an extremely broad interpretation, which includes the Far North and the Russian Far East, taking in dominions lost and gained during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. I therefore apologize in advance with the full knowledge that I have not subscribed to modern administrative boundaries or prevailing political correctness about who or what is Siberian. I have instead gone by Anton Chekhov’s description: ‘The plain of Siberia begins, I think, from Ekaterinburg, and ends goodness knows where.’

There were three significant revolutions in early twentieth-century Russia. The first was in January 1905, after government soldiers opened fire on peaceful protesters in St Petersburg in what became known as ‘Bloody Sunday’. Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, known by his alias, Lenin, and Leon Trotsky became the main architects of the two socialist revolutions in 1917 – the February Revolution, and the October, or Bolshevik, Revolution. I tend to refer to the events of 1917 collectively as the Russian Revolution, unless otherwise stated.

As archival evidence has emerged during the last few decades, historians have been able to piece together more authoritative figures relating to Siberian exile under the Tsars, and prisoner numbers in the Soviet Gulag.* Some of the most reliable current statistics† for a basic understanding of the scale are as follows: from 1801 to 1917, more than a million subjects were banished to Siberia under the Tsarist penal exile system. From 1929 to 1953, 2,749,163 forced labourers died in the Soviet Gulag.‡ There are many more numbers, and unknowable quantities of suffering, but I make little further mention of death tolls and prisoner counts. This is because official figures are untrustworthy and other counts remain reluctant estimates.

I use ‘Russia’ to describe the country prior to the end of the Russian Civil War, which ran from 1918 to 1922, when the ‘Reds’ (Bolsheviks, later known as communists) fought the ‘Whites’ (anti-communists, with some factions retaining Tsarist sympathies). The USSR refers to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, or Soviet Union, formed in 1922, which expanded to comprise Russia and fourteen surrounding republics. After the breakdown of the Soviet regime following a tumultuous period of economic restruc turing known as perestroika, Russia changed its name. On 31 December 1991, it became known as the Russian Fed eration, which I shorten to Russia for the sake of simplicity. To track these political changes, as well as key moments in the history of Siberia, please refer to the brief Chronology at the end of the book.

Until 31 January 1918, Russian dates conformed to the Julian, or Old Style, calendar, which ran between eleven and thirteen days behind the Gregorian, or New Style, system. I use the Old Style for events that took place inside Russia before the Revolution. I use the New Style thereafter.

Sometimes I am the one out of synch. Although this book is written as a continuous journey for narrative coherence, my various research trips were not all taken in the order they are documented. Sometimes I had to return to a location to deepen my research. I also had to work with opportunistic leads, inclement weather and unpredictable scrutiny from Russia’s FSB, the state security and surveillance apparatus and a direct descendant of the KGB. I mostly travelled Siberia in winter, not summer. The main reason for this was a dangerous allergic response to the region’s mosquitoes – as vicious as the Siberian legend suggests, that they were born from the ashes of a cannibal.

The Great Patriotic War is a term widely used by Russians to refer to the Soviet experience of the Second World War. I have used the most familiar, Western version of people’s names. I have tended to avoid patronymics, as well as the feminine forms of a surname customarily used for Russian women. Nicholas II is the common name by which most readers will know the last Tsar. The other Nikolais I met, along with the Alekseis, Marias and Lidiyas, I don’t anglicize. I like the sound of their Russianness, though these decisions are idiosyncratic. The transliteration of Russian to English follows the Library of Congress system in the Source Notes and the Selected Bibliography only.

All interviews have relied on interpreters, who have stuck as close as possible to the spirit of intention, as per the advice of the Hungarian composer Franz Liszt about transcribing orchestral works to the piano: ‘In matters of translation there are some exactitudes which are the equivalent of infidelities.’ Many of my interviews were digitally recorded. Original direct quotes were re-checked with sources, and sometimes subsequently amended to refine meaning.

I relied on one interpreter more than any other: Elena Voytenko, whose fortitude helped me through many a black hole in Siberia. On a number of my trips to Russia, I was also joined by the American photographer Michael Turek. I picked up all manner of local guides, from music teachers to mountain-rescue specialists. I travelled ‘on the hoof’ wherever a lead might take me, by plane, train, helicopter, snowmobile, reindeer, amphibious truck, ship, hovercraft and taxi. I also hitched lifts with oil and gas workers. False leads induced a certain amount of backtracking, which was another reason for return visits.

Siberia’s Altai Region (capital, Barnaul) is contiguous with the Altai Republic (capital, Gorno-Altaysk); the latter is the more remote and mountainous. For simplicity, I use the term Altai to cover both. I have gone by the modern designation of Russian place names (since 1991, cities have generally gone back to their pre-Revolution names). St Petersburg I refer to by its current name as well as Petrograd (from 1914 to 1924) and Leningrad (the name from Lenin’s death until the end of the Soviet Union in 1991). Again, my decision is idiosyncratic. The events that took place in this city during the Leningrad Siege from 1941 to 1944 were so monumental, the name is hard to cleave from specific historical incidents. This is not so true of Novonikolaevsk, now known as Novosibirsk. Before starting this book, I hadn’t heard of either.

________________

* GULAG is an acronym for the Main Administration of Camps – in Russian, Glavnoe upravlenie lagerei – which is now more commonly used as a proper noun to describe the whole horrifying system of Soviet penal labour.

† At the time of this book’s first publication: 2020.

‡ Numbers relating to Tsarist exile are taken from Daniel Beer’s The House of the Dead (London: Allen Lane, 2016). Anne Applebaum’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Gulag: A History (London: Penguin, 2004) hesitantly cites the Gulag death toll. Both books are critically important to an understanding of the statistics, while both also acknowledge the unreliability of any final number.