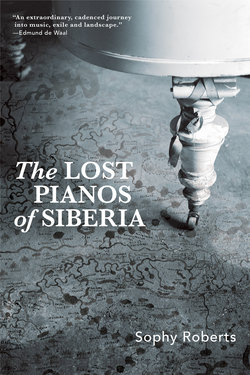

Читать книгу The Lost Pianos of Siberia - Sophy Roberts - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

Traces in the Snow: Khabarovsk

IF YOU MEASURE SIBERIA’S width from the Urals in the west to the last spit of land that makes up the Chukotka Peninsula on Russia’s Arctic seaboard, then Siberia is wider than Australia, its Pacific edge just fifty miles shy of North America to the east. In Siberia, there are lakes that are called seas, with some parts so thinly populated that travellers past and present have frequently compared Siberia to the moon.* This analogy would work if it weren’t for the animal life that thrives in Siberia’s icy vaults. Once upon a time, when Eurasia wasn’t such a mighty, contiguous landmass, the Urals formed the shore of an epicontinental sea dividing Europe from Asia. Flora and fauna migrated across the land when sea levels fell, except for one species that managed to more or less respect the borders of this long-forgotten biogeographical divide: a plucky little Siberian newt you seldom find west of the Urals. A fierce swimmer and evolutionary hero, the pencil-long Salamandrella keyserlingii can live for many years inside the permafrost, in temperatures hitting fifty degrees below. In The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn describes how in Stalin’s labour camps, higher thoughts of ichthyology would be cast aside for a mouthful of the prehistoric flesh. If famished convicts were ever to chance upon such a thing, he pictured the scene: the salamander would be frantically thawed on the bonfire and devoured ‘with relish’ by hungry convicts elbowing each other out of the way.

On a cold winter morning in March 2016, I landed in the city of Khabarovsk in the Russian Far East, an eight-hour flight from Moscow and about a day’s drive from the Pacific, where the coast is so choked with ice you can walk out on to a frozen ocean. It felt about as far from home as I could get while remaining on this planet. With the idea of Siberia’s lost pianos nagging at my conscience, I had made a couple of cursory attempts to see if my quest had legs, but the real purpose of my trip wasn’t to find an instrument for the Mongolian pianist I had befriended. I had come to track something far rarer – to write about the Siberian, or Amur, tiger. If there were a decent story to tell, I would sell it to a British newspaper. In winter, when the forest is covered in snow, it is easier to see a tiger’s footprints.

Panthera tigris altaica, an icon of the Russian wilderness under heavy federal protection, is on a fragile edge. There are only an estimated five hundred of these creatures surviving in the wild, their rarity almost on a par with the few snow leopards left in Siberia’s Altai Mountains close to Mongolia, and the Amur leopard, which is down to eighty or so animals where Russia borders China and North Korea. For centuries, the Chinese came foraging for ginseng roots in these eastern forests, and to poach tigers for traditional medicine. Then in the late nineteenth century, big-game hunters shot them for trophy pelts until tiger hunting was banned in Russia in 1947. These days, professional conservationists are lucky to encounter a wild tiger more than once or twice in a lifetime. Before the Korean tiger researcher and filmmaker Sooyong Park started his work in 1995, less than an hour’s footage had ever been recorded of Siberian tigers in the wild.

I arrived in Khabarovsk expecting everything to be dead and infirm, unbearably cruel and devoid of enchantment. Siberia had functioned for more than three centuries as a prison. It had been shredded by revolution, civil war, Stalin’s reign of terror and the impact of the Great Patriotic War. I turned eighteen in 1991, the year the USSR collapsed. Twenty-five years later and numerous post-Soviet images were seared into my mind: a factory here, an abandoned tank there, and a sickly forest eaten away by industrial pollution.

Not that I was unique in my preconceptions. In 1770, Catherine the Great complained to the French Enlightenment philosopher Voltaire: ‘When this nation becomes better known in Europe, people will recover from the many errors and prejudices that they have about Russia.’ When Tchaikovsky met Liszt in 1877, he remarked on his nauseatingly deferential smile, which was heavily loaded with condescension.

‘Pay no heed to the boasting of Russians; they confuse splendour with elegance, luxury with refinement, policing and fear with the foundations of society,’ wrote the French traveller the Marquis de Custine, of the Russia he found around the time Liszt was in St Petersburg. ‘Up to now, as far as civilization is concerned, they have been satisfied with appearances, but if they were ever to avenge their real inferiority, they would make us pay cruelly for our advantages over them.’ De Custine – described by one historian as a camp, – was a powerful influence in the West’s early (and enduring) perception of backwards Russia: ‘The Russians have gone rotten without ever ripening!’ he wrote in 1839, citing a well-known aphorism of the time. If the West still looks down on Russia, it has an even more pronounced attitude towards Siberia – and it was ever thus. ‘There are few places on the earth’s surface about which the majority of mankind have such definite ideas with so little personal knowledge as Siberia,’ observed a British economist travelling through the country in 1919.

On first encounter, Khabarovsk was wrapped in this fog of stereotypes. It was a leaden sprawl in monochrome with neither the brutal beauty of Moscow nor the peppermint-coloured grace of St Petersburg. There was a museum about a bridge, another about fish, a third about the history of gas extraction. The snow was dirty, like the midnight stipple on an old television channel. Trails from smokestacks streaked the sky with worry lines. Signs of urban prosperity were thin: a European-style boulevard with blushes of pink paint, and a promenade with white railings used as a set for wedding photographs beside the frozen Amur River. At least I hadn’t come in summer, when the surrounding forest turns to swamp blackened with mosquitoes, their wings pricking the surface like drizzle, their swollen corpses falling into every spoonful of soup.

Aleksandr Batalov, the local tiger researcher I had come to meet, didn’t speak much at first. In his middle sixties, he was broad and short, with grey eyes and wide shoulders honed by the pull-ups he practised on a bar that hung across the doorway of his cabin in the forest. He wore a pair of felt boots gifted to him by a colonel in the Russian army, and mismatched camouflage fatigues. Following us in another van out to the forest was a driver carrying food supplies and extra blankets. The driver’s face was sallow, scored by a lifetime of pulling hard on cigarettes, his lack of charisma matching a description that the early-twentieth-century explorer Vladimir Arseniev gave to the local men who joined him on his expeditions through this territory. ‘The Siberians were selected not for their social qualifications,’ he wrote, ‘but because they were resourceful men accustomed to roughing it.’

Arseniev was right. Our driver was efficient when the engine coughed and cut, but not once did he attempt conversation. The Uzbek cook at Aleksandr’s research base wasn’t much of a talker either, leaving me to wonder how the Silk Road town of Samarkand and the golden roads that once led to it must have hit a catastrophic slump in fortune for a man to venture here, to abandon the fat peaches of his native Fergana Valley in Uzbekistan for Siberia’s bony fish. For the Uzbek, it was unclear if Siberia marked the end of the road, or a new beginning.

We rumbled out of Khabarovsk, passing workers gathered at the bus stops, their breath suspended in the air. We passed a shopping mall on the city’s outskirts, where a few months prior, a brown bear had wandered in. The bear was shot and bundled into the back of a white van, head hanging like a teddy without its stuffing. Aleksandr then described a boar that had recently rammed the doors of a Khabarovsk hotel. Each of Aleksandr’s stories implied that Siberia was teeming with wildlife, when a century ago, Dersu Uzala, the indigenous trapper who led Arseniev’s expeditions, warned of the environment’s demise: he gave it ten years before all the sable and squirrel would be gone.

Dersu Uzala belonged to the Nanai tribe, also called ‘the fishskin Tatars’ after their habit of using dried fishskins for clothes. In the late sixteenth century, Siberia’s population comprised almost a quarter of a million indigenous people living as nomads, fishermen, hunters and reindeer herders. The Nanai were one among around five hundred unique Siberian tribes. Belief systems were shamanist and animist.

Dersu Uzala, photographed c. 1906, acted as a guide for Vladimir Arseniev’s expedition, and twice saved his life. In 1975, the story was turned into an Oscar-winning film, Dersu Uzala, by the Japanese director Akira Kurosawa.

This mix began to change in the seventeenth century. Religious dissidents who refused to sign up to reforms in the Russian Orthodox Church fled east of the Urals to escape repression in European Russia. They formed ‘Old Believer’ communities, which still exist today. The process of Russian cultural assimilation among minorities picked up under Catherine the Great, with a rapid expansion in Siberian trade. Disease, brought in by the influx of outsiders, also spread into indigenous communities. By the middle of the seventeenth century, Russian settlers – as opposed to just convicts, who were only ever a small proportion of Siberia’s new population – were outnumbered by indigenous Siberians at a ratio of around three to one. By the end of the nineteenth century, that ratio had changed, with five citizens of Russian descent to one indigenous Siberian. With these demographic shifts – not unique to Russia, given what the Europeans were up to with their overseas colonies – Orthodox Christianity soon prevailed. Forced collectivization in the Soviet period, as well as a stringent ‘Russifying’ political ideology, then brought the last of Siberia’s indigenous outliers into line. Shamanism, banned by Lenin in the twenties, is no longer close to what it was before. With the old blood mixed up with the new, Slavic features are found in faces that look a little Korean, Mongolian, even Native American. Siberia’s original hundred-odd languages are disappearing. The Kerek tongue, spoken in the Far North, is close to extinction. There are more tigers left in Siberia than there are Itelmen-speaking people.

There had been fresh snowfall overnight in Khabarovsk. The further we drove, the thicker the drifts. By the time we turned off the road at the village of Durmin, the track was smothered. Marsh grasses arced under the weight, and seedheads nodded like silver pom-poms. In the solitude, it was hard to imagine the Russian taiga – the so-called ‘tipsy forest’, named after the skinny, deracinated trees – rustling with sable. This relative of the marten once thrived in the wooded belt between Russia’s grassy southern steppe and the northern tundra inside the Arctic Circle. From the mid-sixteenth century, sable was Russia’s ‘soft gold’, accounting for up to ten per cent of the state income, its silken fur, each dark chocolate hair tipped in silver as if sprinkled in morning frost, drawing bands of ruffian Cossack mercenaries. Answering to the Tsars, the Cossacks colonized Siberia so rapidly, they reached the Pacific within sixty-odd years of making their first incursion over the Urals.

Aleksandr spotted a field mouse on the road, which we just avoided running over. ‘Don’t look after the shrew, and we have big problems,’ he said, explaining how the natural chains are breached with every felling of an oak tree. When predator and prey lose their place in the world, tigers are forced to migrate into territory where they don’t belong. He told me to listen out for ravens, which cluster around a kill. He wanted to show me a nuthatch, which was his favourite bird. Between sharing facts about the forest, Aleksandr talked a little about politics – how the socialist idea was a good one, though other nations wouldn’t have stood it for so long. Russians have an ability to endure, he said, to test an idea from the beginning to its end. He described the vacuum that was created, and his disappointment, when the USSR disintegrated. He talked about the riverside cabin of his Siberian childhood, how it was surrounded by rolling wheat fields and mountains where he used to collect berries which his grandmother folded into yoghurt. A large basket took two hours to fill. It was on expeditions like this that he learned to observe the behaviour of animals, including hares, birds, roe deer, foxes and wolves. At the age of five, he spied on a family of cranes, hiding himself in the pond so that only his eyes and nose were above the water. But the cranes got angry and attacked him.

An eighteenth-century engraving of an indigenous Siberian fur trapper. The indigenous people were heavily exploited, earning a copper kettle in return for the equivalent skins they could squash inside the vessel.

Bit by bit, Aleksandr began to reveal his motivations for protecting a species he feared could no longer protect itself. It didn’t matter that he rarely found a tiger. Like the researcher Sooyong Park, who has written so eloquently about his years sleeping in hides waiting for Siberian tigers, Aleksandr was content looking for its tracks and trying to reason with the loggers damaging the habitat on which not just the tiger but also its prey depend. Aleksandr was fascinated by the tiger’s status in Russian culture. He described all sorts of superstitions around tigers – like the one about a priest who in Tsarist times wore a tiger skin under his cassock to avoid being bitten by the town’s stray dogs – and gruesome true stories. A few years ago, a good friend – a game warden – woke up to fresh tracks, recorded the sighting in his diary and then set out for another winter cabin. Along the way the tiger ambushed him.

Then Aleksandr grabbed my hand, squeezed it and stopped the van. On the ground ahead of us was a perfect line of pugmarks – each wide pad fringed with four round toes. As I cautiously stepped out of the truck and put my hand against the pugmark in the snow, the scale became real. The front paw pad measured nine centimetres at its widest point. A six-year-old tiger, said Aleksandr, and probably a male.

For another mile, the tracks followed a straight line then looped off the road, where the tiger had wandered off to add its scratch marks to a tree. Aleksandr said we mustn’t follow. If a tiger has prepared itself for an attack, there is no way a man can act quickly enough. Tigers are clever, with a capacity for premeditated revenge. They like walking in our footsteps, said Aleksandr, preferring the feel and efficiency of compressed snow.

We drove on at a crawl, until we came to the impression where the tiger had been sleeping and left its barrel-shaped belly pushed into the pack. Golden strands of hair were still embedded in the white. A few steps beyond, there were scarlet specks of blood, the stain so fresh that the colour was still bright with life. This would have been enough – to touch the blood from a Siberian tiger’s kill – until we turned another bend in the track. The tiger was sleeping, perhaps eighty metres distant, in the middle of the road. When he raised his head, I could see the dazzling stripes, the crystal snow falling off his back, the poise of his long tail, which had nothing to do with fear.

That night, I had difficulty sleeping. When a log hissed then snapped in the fire, I thought of the single bite it takes a tiger to break the neck of a deer. But it wasn’t fear that was keeping me awake; it was intoxication. Part of me wanted to leave Durmin and the discomforts of Siberian life – the anxious nights, the frozen meat hung up in the porch waiting for a clumsy hacking from the Uzbek cook – but a far larger part of me wanted to stay.

There was something bewitching about the taiga now I was inside the forest, something which ran deeper than those glinting incisions of curling waterways you see from the air, the forest scrawled with tightly folded S-bends as if the land is whispering somehow. There is a covert charm to Siberia, like the maps by Semion Remezov, who drew up the first significant cartographic record of the region at the end of the seventeenth century, when Peter the Great posted him to the Western Siberian town of Tobolsk.*

Remezov had a cartographer’s eye for the dimensions of the land, and an illustrator’s flourish. His maps are decorated with elaborately inked fortresses, sickle lakes and wooded copses. Many of Remezov’s manuscripts are dotted with Siberian creatures – flying horses, a pack of wolves, horned antelopes – and effortlessly fluid line-drawings of grand cathedrals, weaponry and soldiers. His work is still the most perfect distillation of Siberia’s lures, rendered in beautiful, calligraphic loops. Painted in watery blues, the tributaries reach across the pages like the veins of the Empire itself, each spur as finely drawn as a fishbone. Remezov drew Siberia with a delicacy that belies its ferocious reputation, from the fraying rivers spilling into lakes the shape of love-hearts, to forests hollowed out by lazy streams making their northern journey to the Arctic.

In my mind’s eye, Siberia began to burn with possibility, in the faults and folds of a landscape full of risk and opportunity. Names began to roll out of the emptiness: Chita, Krasnoyarsk, the River Yenisei, which is one of Siberia’s four great rivers, along with the Amur, Lena and Ob. I was captivated by how marvellous it would be to find one of Siberia’s lost pianos in a country such as this. What if I could track down a Bechstein in a cabin far out in the wilds? There was enough evidence in Siberia’s musical story to know instruments had penetrated this far, but what had survived?

On my last evening in the forest, I mentioned the idea to Aleksandr over another thin broth of dill and fish-heads with boiled white eyes – the notion of returning to Siberia to look for an instrument.

At first, Aleksandr didn’t address my idea. He talked about his personal history, and his father’s songs. In the Siberian village where Aleksandr was raised, his father had been a music teacher and accordion player; his melodies were well remembered. Aleksandr told me about a musician who ten years before had wanted help moving an old piano into his home in Khabarovsk. He described dragging it to the apartment block then up numerous flights of stairs. Then Aleksandr went back to scanning his camera-trap footage of tigers, leaving me to picture a piano being hauled across pavements of ice. Nothing more was mentioned about music until the last morning as we readied to leave the forest. Aleksandr reminded me of the tiger we had encountered on the path, and the snow pricked with blood. The sighting would be my talisman, he said.

‘You must give it a go,’ he urged. ‘The tiger will bring you luck.’

In my last hours with Aleksandr, a powerful attachment formed in my mind, that I might find as much enchantment in the historical traces of instruments through Siberia as Aleksandr did in the footprints of a rare animal. Instead of tigers, I would track pianos. By knocking on doors looking for instruments, I would be drawn deeper into Russia and perhaps find a counterpoint in music not only to Siberia’s brutal history but to the modern images of this country reported by the anti-Putin media in the West. Driving back out of the forest, I passed the spot where I had seen the tiger. If the silver birches were spirit trees, as the Nanai people believed, I wondered if I should have made a passing act of totemism to persuade Siberia to keep me safe.

When I returned to England, I started looking for good leads. I contacted Pyotr Aidu, a Russian concert pianist who had amassed a Moscow orphanage for abandoned instruments. In his collection, there was an 1820 English Broadwood, and a Russian-made Stürzwage wearing the scars of a firework detonated under its lid – a good brand, much overlooked, and one I should look out for, he advised. He said there were voices worth seeking out in old instruments. In his opinion, restored pianos have better sound than their modern counterparts.

Others disagreed. Numerous piano experts told me that all the reconstruction in the world wouldn’t necessarily make a dead piano sing again. I was told Siberia was a terrible place for pianos, especially because of the low humidity in winter. I was warned that there were strict laws to protect against artefacts of more than a hundred years old leaving the country; more than fifty years, and a piano would need, at the very least, special permission. I decided to home in on Siberia’s old trade routes, including the Trans-Siberian Railway towns that thrived in the nineteenth century, at the same time as Russian pianos spread east. I would use television adverts, social media and local radio channels to track down private instruments with stories. I would need Siberia’s piano tuners on my side. They would know best where history was still to be found in Russian homes. That was by far the most important part to me: gathering the stories, then seeing where they led.

As I marked up my map, I started to understand more clearly how the Tsars’ expansion into Siberia, and their establishment of the exile system, coincided with the state’s desire to bring European piano-making to Russia – and how instruments had trickled into this wasteland over the course of three centuries, contributing to the waves of Russification across old Siberia and lost indigenous cultures. Part of me hoped that the piano, which was such a magnificent symbol of European culture, hadn’t yet made it into a nomad’s tent. Every piano I found would be a victory, but I also wanted to seek out the corners of Siberia which had been left untouched – the parts not even Catherine the Great had managed to pull into line during a reign that helped turn Russia into a European musical nation, and Siberia into a synonym for fear. I not only needed to travel into the musical history of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but also to look at the piano’s domination, its shifting dominions, and its social role. Only then would I understand the value of something precious in the physical peripheries of Russia at a time when piano music was experienced ‘live’, before radio and recorded music shrank the world. By following the pathway of an object, I would get closer to understanding the place. I would learn that an object is never just an object – that each piano sings differently because of the people who used to play it and polish its wooden case.

________________

* The contemporary American author Ian Frazier recounts a story about Westerners flattering the seventeenth-century Tsars with the idea that their territory ‘exceeded the size of the surface of the full moon’. It didn’t matter that it was potentially untrue: ‘To say that Russia was larger than the full moon sounded impressive, and had an echo of poetry, and poetry creates empires.’ This is one of my favourite lines ever written about Siberia – a remark which speaks to the power of the great Siberian myth. Travels in Siberia (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010).

* Two of Remezov’s maps are published on the endpapers of this book.