Читать книгу The Book of Safety - Yasser Abdel Hafez - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

I am the chance at deliverance that Sawsan al-Kashef hoped for. I did not hang the photograph of her with her lover right beside her wedding portrait on the wall of her home simply in order to prevent her husband reporting the burglary. If that had been all I was after, I would have threatened him with other, more important documents. Was it a coincidence, his total absence from her secret album, from the pictures she’d stockpiled from different events: at school, on the beach, trips to Europe, alone in a bar with only a glass of beer for company, dancing with a friend at a wedding while the newlyweds’ relatives looked on grimly?

It was my decision to restore her to how she had looked at no more than seventeen, two fingers placed in her mouth (most likely an attempt to whistle); and up above, on one of the balconies, a figure pointing down to her; and on the balcony opposite, a man and woman sitting close together, his arm around her neck, and in front of them two cups of tea on a small table. The Seventies—I reckoned it from the clothes and a freedom whose fragrant breeze I almost scented as I studied the details. Sawsan al-Kashef’s secret album, and its incongruity beside the scowling portraits on the walls, ushered me into her story. How was it that life had changed for her to such a degree?

To protect the reputation of the al-Adl family, what Mustafa testified to that day was not to be made public, a secret preserved by three who kept their pledge: the thief, the interrogator, and the transcriber. But I’m an author now. What do they expect? It means nothing to the writer that you make him swear by honor, integrity, or ethics. Writing, for those initiated into its secrets, means nothing if not the betrayal of what is stable and immutable. And why should Nabil al-Adl believe that his family is so exalted that any mention of it should be scrubbed from the transcript of the interviews? More importantly, Sawsan al-Kashef’s story and what happened to her are vital in clarifying the reasons that led Mustafa Ismail to embark on his project as a whole. And so: I spill.

Mustafa knew nothing of the link that bound my boss to that home. His Book of Safety didn’t cover coincidences like that. And so he didn’t understand why the interrogator was so vexed that he’d exposed that woman’s secrets to her husband in such a ruthless fashion. But as I saw it, he wouldn’t have cared even had he known. He had his convictions, and these made him a believer in what he embodied.

Every home I entered brought me one step closer to what I did not know.

The only sentence concerning that incident that I entered into the transcript of his confessions. Al-Adl made his wishes quite clear as he left his desk for the sofa in the room’s far corner. He plucked the pen from my hand, capped it, and laid it on the paper before me. To the page that would remain blank, I apologized. That evening I was to enjoy being an audience and nothing else—a child whose father reads him a story before bed. But what about my fingers? I laid them against my thigh, tapped out a tune that was buzzing around my head, whose title and composer I’d forgotten.

Nabil’s voice, apologizing to Mustafa for the interruption:

“Please go on. Sorry.”

Several jobs in, my comrades had their instructions off by heart—what we wanted and what we couldn’t use; what we mustn’t touch; what, if we took it, would implicate us in a situation we couldn’t deal with. There are some things whose loss people are unable to forgive, usually when under some form of compulsion: important documents, guns. We steal what can, with a little menacing, be forgotten. My colleagues carry out their tasks as befits a contemptible band of thieves, while I wander monk-like through the home, feeling out its detail. At first, this involved no more than the search for documents—blackmail material—but it soon became an end in itself. I came to love these close inspections of how our victims lived, and the experience taught me to make quick and accurate judgments of their homes. Here, with its predominantly feminine touch, the woman is in charge. This one is devoid of love, evident from the absence of the harmony that affection brings. There are homes you’re at ease in, that bewitch you the moment you enter. Have you heard about thieves who doze off in the homes they enter, only to be surprised by the return of the owners? I used to think this was the stupidest kind of larceny, and the laziest, until I had perfected my trade and experienced the same thing myself—the sense that this is my home, this woman who’s hung her picture on the wall is my wife; her underwear, left lying with typical negligence on the bed or in the bathroom, keeps her body present.

My companions left me to my own devices, knowing that my presence was a guarantee of our safe departure. It was as though we were guests to whom the generous owners had gifted some of their possessions—poor relatives to rich folk who gave clothes to us and our children, saying that they were unused, and yet they weren’t quite right for us. But we would accept them, convincing ourselves that we were exchanging gifts.

“Exchange gifts and exchange love.”

And yet we were recalcitrant paupers, mature enough to admit that we were resentful for our lesser standing, that this resentment would spur us to gift them, too, something to keep us in their hearts—something hurtful and painful that would perhaps upset their code of values and principles. They would stop receiving poor relatives and wouldn’t give them gifts. Not so freely. No call for tenderness.

I told you that every home I entered brought me a step closer to myself. Everything I stole led me to a part of myself and what I wanted. It was more like therapy than anything else, which is why I became addicted to living within the lives of others.

I no longer cared what we came away with. My treasure was the details. Unlike that woman, I possess almost no photographs from childhood. Photography was another expense whose cost we couldn’t bear. The camera I inherited from my father he had rarely used himself, and after his passing we kept it only for special occasions, the kind that are carefully prepared for precisely because they will be photographed. Which is why I cannot remember how I looked, except by relying on a memory that shifts about according to the whim of the moment. Among the papers left by my father, reserve officer Ismail al-Sayyid—the majority of which were comprised of official documents, letters addressed to him from military command, and a few photographs of landscapes, there was a single picture—one single solitary picture—from which I know what he looked like. Standing on the seashore in Alexandria (so he’d written on it) with a group of colleagues, all aping the pose of bodybuilding champs: one arm bowed out from their sides, the other held skyward in a straight line, the face turned with it, out as far as it would go. Little gods who fell and never knew why.

I lost myself in Sawsan’s life. Compare these hidden pictures with the official portraits on the wall: the bearded husband, the young women in hijabs, the son who looks more like his father than her. And then an exception, a group shot: her with a little girl at the seaside. The little girl is pouring a bucket of water over her mother’s head. Of the three children, she seems to be the closest to Sawsan. Alone among the pictures on the wall, their expressions hold some kind of rebelliousness, while those of the father, son, and other daughter possess a serenity and placidity in keeping with the piety hinted at by numerous small details scattered around the apartment.

Mustafa reclined on a big, black leather chair in a pose that matched his self-confidence, his hands on the armrests, talking languidly as though seated in his own office with old friends who could discuss without embarrassment the smallest details of their lives. I was sitting on a similar chair, but drowning in it. I tried sitting according to the image I had of myself, but it came off as distinctly forced. What we think of ourselves does not always pan out in reality. He saw greatness in himself, as I did in myself, but the practical application of this thought proved his vision to be the correct one. Was I deceived, then, or was it just a question of practicing to make the idea correspond with reality?

Practicing greatness!

An excellent title for a book dealing with the difficulties of a certain class of person looking for solutions to predicaments like mine: in search of that harmony between the idea of oneself and the passage of that self through life. I made do with perching on the edge of the chair, leaning slightly forward: a student in his teacher’s chambers patiently absorbing his lessons until he’d formed sufficient convictions to leave him puffed up and proud.

When the thieving first began, it was driven by an anger that I could only expend in that particular way. This does not constitute any admission of error—quite the opposite! It’s just that I was not conscious, exactly, of the factors that were making me act this way. But it was in this woman’s home in particular that I realized I was in possession of a message, and one that I must carry out. Call me a devil if you must, but I have the power to expose the fakery in whose prison we pass our lives.

Nothing is done except at my signal. I am involved from beginning to end. The true leader goes at the head of troops, and this is what ensures that he keeps his position.

My presence on the ground during operations safeguards my project. No matter how adept and well-trained your foot soldiers, they cannot cope with surprises.

Leadership means swift reactions, calm in the face of crises, reassuring the men that they will always be protected from things they have no idea how to handle.

Mustafa Ismail

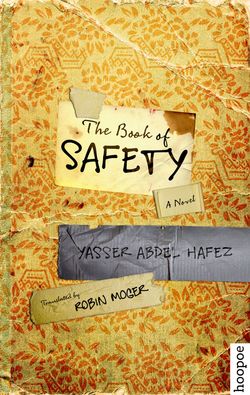

The Book of Safety