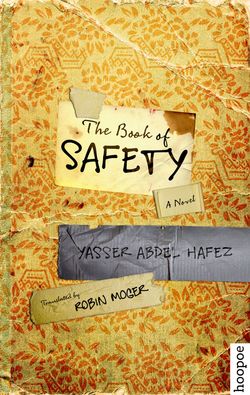

Читать книгу The Book of Safety - Yasser Abdel Hafez - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

“Would you like to know your end, then arrange your life accordingly?”

I directed the question at Dmitri, owner of the Sappho bookshop, and his friends, still and silent, arrayed in the ancient photograph’s tableau. I had been coming to the bookshop with my father since I was little, and not one detail had altered, every figure in the picture holding position. With this photo, Dmitri had made the most beautiful period of his life immutable. There he stood in his suit, white and cut in the Forties style—were it not for the red handkerchief in his breast pocket, he would have looked like a little puddle of milk. To his right and left respectively, Maria and Helene, and on the opposite side of the picture his friend with the tricky name I couldn’t remember.

Dmitri’s reticence about personal matters opened the floor to speculation. From time to time, I would dream up different explanations for this picture, for this four-way tie that ended with three off to Greece and Dmitri staying behind. The authentic Shubra kid, passionate about Egypt. That friend of his was bound to leave; the sharply masculine features and athletic body, his simultaneously simple and elegant clothes, spoke of ambitions that no longer belonged in the burgeoning dictatorship. The girl on the other side of the picture had traveled with him, that much seemed certain. Today’s backstory was that she had been his lover. Her casually parted legs went with his liberated air, while her companion’s conservative posture suited Dmitri’s commitment to dapper formality on an occasion that didn’t warrant the effort. But unable to endure his reticence she had chosen to follow her friends.

In front of the pyramids and the Sphinx: two men and two women mounted on four camels gazing at the horizon, trying to mirror the still-majestic statue. Yet they fell short of the effect they strove for. A pharaonic curse had slipped out from the pyramids and into the four camels, lending them a satirical spirit that spurred them to lampoon their riders: gazing, like them, defiantly into the distance.

Yes indeed, Mustafa. I would like—would long—to know how it will end for me and to arrange my life accordingly.

Dmitri heaved his body out of the storeroom I had never been permitted to enter. There was no longer any resemblance between him and his portrait, but beginnings tend to lead to endings, and he had answered a propensity for fatness, doubling the size of every cell in his body. He raised his glasses to his eyes and wiped away beads of sweat. Huge effort was expended in the storeroom, which was why, to obtain a book, lengthy negotiations were unavoidable. The book was a rare edition, he would insist: unobtainable, even from the National Library, which—like every square foot of this country—had succumbed to neglect! I smiled to myself. Then:

“You were speaking to me?”

“No, no, Uncle Dmitri, be well.”

Always suspicious and never troubled to hide it. Innocent behavior could take on quite inappropriate significance with him, and so to prevent his misgivings spreading I pretended to study the book in his hand.

He had not accommodated himself to the frailties imposed by his age, working around the clock to prove he was up to it. More than anything, he loathed his faculties being called into question, as though he were some pitiable pensioner. I had made a mistake. I should have told him straight that my habit of speaking to myself had slipped out of my control; then he would have smiled, wheeling out that brand of empathy with which he maintained a distance between himself and others. The point being that he would have been reassured no defects had been detected in any of his faculties, for that would signal that the breakdown had begun.

He set the book on a stack of lowbrow crime novels, the ones he had refused to trade in when they first became popular, hating the idea of them, the way they were written, even their covers—then weakening when confronted with the lure of their profits. He concealed the title of the book he held from me, determined to spin out the game of enticement that he played so well.

“Cryptography is like magic. It first requires you to believe that reality does not exist. A fundamental requirement, this: without it you will see only signs and symbols.”

He fell silent to catch his breath, preparing for the next sentence which was to be considerably longer. It would incorporate, perhaps, the difference between cryptography, a science, and magic, a supernatural force on which one should never be so rash as to rely entirely. How could one combine the two?

Then the conclusion: “Thus all innovation throughout history.”

This was Dmitri’s motto, which he would shape and shunt into any topic, even food. I often thought to myself that he existed in a room only he was allowed to enter. He would invent things to accommodate this theory of his, but I was unable to guess at the nature of the mutually incompatible elements he was combining—nor, I believe, could anyone else. For Dmitri was a living, breathing dictionary, with effrontery enough to learn everything about everything by reading a book about it. And yet, because he who excels in speech finds it difficult to act, things never panned out for his theory as they should. Ever since our relationship had become properly established, I would hear him talk of it—maybe as my father had before me. We exist in a mesh of unchanging sentences, then seek out new ones, fleeing the tedium of repetition and uniformity. Take the strategy adopted by a close friend of mine, Lotfi Zadeh: unable to bear his father’s oft-repeated line on freedom, he had voluntarily joined the ranks of a group that regarded such things as heresy.

Behind me, the sound of panpipes trilled. One of the constants in my life. As a child, I would go ahead of my father to shove the door, which would knock the machine mounted behind it and make it play a tune. Many times, I’d leave the pair of them and go back out into the street, then return to push the door and hear the music once again. My father would tell me off, tell me to mind my manners, and Dmitri would cry, “No, no, parakalo, please, parakalo, let the boy have fun.”

With uncertain steps, accompanied by the tune, a young woman came in. Her dress was covered with flowers, and her hair so thick that I was quite entranced and didn’t even glance at her face. She looked about, then stood there, a few paces off, her head bowed and as still as though turned to stone by Medusa. This is what Dmitri looked for—all his customers were different in some way, somehow dreamy and disoriented; summoned by the sad sound of his panpipes, they never regained themselves thereafter.

Seeing him distracted with the girl, I made to leave. He wasn’t so insistent that I stay.

“We must finish our conversation. . . .”

“I’ve got an important appointment.”

Out I went, hugging the book—Enigma—to my chest and hoping it would help me find my way to a starting line. Mustafa’s confessions were a web of riddles. He quoted from books, quotes that were sometimes quite beside the point. Among his words lay a message of some kind, perhaps one that transcended reality—but not, as Dmitri would put it, to the extent of negating it.

No one who knew my good-hearted Greek friend would subject the views he expressed to intense scrutiny, nor blame themselves for seeking to escape the chatter of a lonely old man, devoted to his customers, who wanted nothing more than someone to listen to him for a while.

From home to the bookshop was fifteen minutes on foot, more or less the same distance that separated the bookshop from the café—a full quarter of an hour which, until that moment, I’d never before considered how to spend. (But considering late is better than never at all). I stood outside Sappho, the bookstore whose golden anniversary we’d shortly be celebrating, its signage over my head. Beside it stood Golden Shoe Footwear, then Koshari Delight. This was not as incongruous as it might seem, quite the opposite: when the sun begins to set, Sappho steps out to don her golden shoe, singing to the pipes of Dmitri’s door as she goes to meet her students.

This was not the Shubra Street laid out by Muhammad Ali, the ruler who forged the modern state. We were now on Lesbos, land of love and beauty. Structures of similar heights and styles harmoniously coexisting with their inhabitants, who contentedly live out an undisrupted and orderly life, spoilt by nothing—nothing save one of the newer buildings, which towered over the rest: the Pharaoh Building, so-called by its neighbors. This was their redress for the arrogance of its wealthy owner—who lived with his family on the first four floors—and that of its other residents, its high priesthood (some of whom owned famous stores in the district, others returnees from the Gulf), bound together by wealth and shared pride in inhabiting the highest and most luxurious building in the neighborhood.

I marked it as my primary target for when I put my planned mutiny into action. Years from now, a young man would come seeking the reason for my transformation from the ranks of the powers-that-be into a bold thief.

I was gathering information that most likely was useless. Was I determined enough to walk in the footsteps of Mustafa Ismail?

The girl emerged from the bookshop, surprised to see me. Ah, how I love these undisguised reactions. Did she think that I was waiting for her? Rest easy now, my thick-haired friend, there is a covenant between myself and Sappho: that I shall never visit harm on her possessions. But at least allow me a sight of that surprised and childlike face.

I watched her walk away with quick, resolute steps, more like a boy trying to act the man, taller than was womanly. She didn’t sway when she walked like other women—that severe body had it in it to rebel against her—and so she had let her hair grow thick, and cultivated flowers on her dress: signs by which she hinted at a hidden softness. The scant breeze plastered the fabric to her body, molding to the lines of her small, rounded buttocks. Every inch of her frame suggested a man somehow possessed by a female spirit—I would only discover how once I’d visited her village and seen the place where she’d been raised.

At the end of Khulousi Street, she stood in a daze, looking left and right. I scampered across to the other side, keen she not catch sight of me a third time. I turned right down Bulaq Canal Street toward the café, fighting the urge to look back and see if my suspicion was correct: that our roles were reversed and she was now scrutinizing me. How did my buttocks look to her? The very thought made them hang heavier. I came to a halt, flustered, making a pantomime of lighting a cigarette, and trying to get a fix on her out of the corner of my eye. At that angle, she was nowhere to be seen. Bolder, I looked around, but she had vanished. I walked on to the café, luxuriating in daydreams that had me a king who cared less for his subjects than for stockpiling women. This girl would be the latest addition to a collection which already included Lotfi’s girlfriend Manal, and Huda, made my girlfriend by some witch’s curse. Taking a scientific approach, setting lust aside, I compared the bodies of all three.

The mission I’d left home specifically to perform had been a failure. I had collected very little information. Who guarded the Pharaoh Building? When was he absent? How to get upstairs without arousing suspicion? And, most importantly, which apartment was currently free of its occupants?

I would have to wait years before I understood what Mustafa’s experiment meant. Young as I was, I’d listened spellbound to what I took to be an adventure story, and because I was learning its details from its leading man this had given me the impression that I had a role to play myself. The missing sixth man of his gang. The mind to match his own, which itself solicited this balance so as to avoid coming to some foolish end that ran against the course of the tale. I had taken on his personality—scouting out locations, going over guard rosters, befriending and bonding with doormen and shopkeepers, making plans to burgle a target (getting in and out, making plan Bs)—enjoying the movement between two contradictory roles. I had regarded it as a chess match, but now I was playing on the primary board. I wasn’t selfish, though. I made sure to initiate certain friends into certain details, stressing that should these details find their way outside our gathering it would mean troubles there’d be no avoiding.

The loser toppled his king and for a few seconds we held him, pityingly, in our gaze. To us, the boards were kingdoms, with soldiers, rulers, and ministers. No one had the right to talk during a match. Brief, concise comments from an early leaver, if he had something worth saying. The moment the king fell, the murmurs would rise up: match analysis, the reasons for victory and defeat, replaying critical moves to avoid making the same mistakes, and, on the margins of it all, the study of openings and recently published books. Our stars. Our heroes. The senior chess players. Great minds denied their birthright, to take their place at the top board.

Ustaz Fakhri moved the café’s cheap board to a table behind him. Some of the pieces fell to the floor, and Lotfi rushed to help. The bishop lay by my foot, head nibbled by the passing years. I fought a powerful urge to stamp down on it and on Lotfi’s fingers, about to pick it up. Soon I’d be needing a visit to a psychologist to find out what lay behind these irrational urges.

Fakhri laid the Samsonite case across his thighs. His eyes narrowed and his thick eyebrows drew together. One of Satan’s avatars: sinister, bulging eyes, the heavy brows almost meeting in the middle, a face held taut by a hidden anger—but a passive devil, too idle to perform his duties; eschewing temptation.

He ran his fingers over the tumblers beside the locks on either side. We stared at him in apprehension and held our breath, waiting for the familiar click that proclaimed the treasure was to hand.

He’d once forgotten the numbers. All efforts to recall them had failed—the suggestion, gloatingly advanced by Anwar al-Waraqi, that he smash the case open had only left him tenser and more irritable. The way to the royal ivory pieces ran through him. We had suggested dozens of numbers based on important dates from his life—his birth, the day he met the king, his visit to Russia—but to no avail. He had asked to be left alone for a moment. The proprietor, Ashraf al-Suweifi, had made a gift to him of his own favorite corner, that he might be alone with his case—a great sacrifice, but the goal was greater still: the royal chess set, symbol of the café and its clientele. And Fakhri would not resort to smashing the case, for that would be an insult to his intelligence and his memory. He would rather the pieces remain imprisoned: an ill omen should it come to pass. It had taken half an hour of total silence before the trial came to an end.

“Want to play?”

I refused, pleading a headache. Ustaz Fakhri offered a game to Lotfi. Moved to the chair facing him, and gave him white straight out. Lotfi concealed his irritation at being thought a lesser player behind the smoke from his cigarette. Anwar al-Waraqi, sitting next to Lotfi, made no effort to conceal the derision on his face. Then he leaned forward to get closer to me:

“So?”

The only Egyptian who made sure to pronounce his Arabic letters properly, a habit he’d picked up living among the Arabs of the Gulf.

“The Egyptians are an idle people,” he would say, “So idle that they can’t be bothered to speak their language the right way.”

He pressed me to tell him about the latest developments in the case. This was his favorite game now. He wanted to leave Shubra for a better life, but he knew that what he sought was not simply a change in location but something that called for a different approach altogether, one that would help him acclimatize to his new environment. And in Mustafa Ismail’s story, he had found what he was looking for. But he needn’t have asked, for I could not free myself from Mustafa’s grip. I would pass on what I saw, in the hope of increasing the numbers of his admirers, carrying out his unspoken wish that his story be preserved against the authorities’ limitless capacity to erase what it wants of memory.

As I explained, Nabil al-Adl had made no secret of his surprise; nothing in his records could explain Mustafa’s violent transformation. Why would a university professor sacrifice all he had and turn to crime? And, more importantly, how and when did he come by the expertise that had made a legend of him? Money wasn’t the motive. He had enough of it, and his qualifications and abilities allowed him to get more in ways that would never have led him to this end. In any case, he didn’t seem hungry for cash. So what had led him to risk all that he’d achieved?

From his seat beside me, Ustaz Fakhri glanced reprovingly at me out of the corner of his eye. He didn’t need to concentrate on his game with Lotfi, but he wished to hear no more. A growing desire to provoke him came over me. I crossed one leg over another. Mustafa’s words filled me with a sense of greatness.

“The reasons are so diverse that they disappear, leaving the crime an act committed for its own sake. Simply put, when ‘safe’ methods fail to guide you to yourself, you have no choice but to try out a set of actions proscribed by convention. And all the dangers this path may bring are preferable to living and dying without discovering who you are. What is it people do, save wake, and sleep, and eat, and fuck?”

Nabil al-Adl had broken in: “And this list of actions is improved when we add steal and blackmail?”

“You view the crime through a filter that your job imposes on you. Such things do not apply to me. I am free of job titles and the need to comply. If you could only obtain your freedom, then we could discuss those actions that are categorized as forbidden, and our right to engage in them.’”

“That’s philosophy, not crime,” was Lotfi’s comment. His eyes were on Ustaz Fakhri: a transparent attempt to curry favor. His position didn’t satisfy him. His desire would bring him down. I had brought him along to help him restore his lost memories of poetry. His knowledge of chess went no further than the general outlines: the pawns, eight identical pieces, the first to be sacrificed. Move by move, the game revealed its secrets and his most salient memories returned, enabling a pawn to reach the far end of the board and be promoted into a thoroughly respectable rook patrolling the northern border of Fakhri’s kingdom. What now?

Long hours I would spend here, seated alongside Ustaz Fakhri, the café’s chief elder and a nationally ranked chess player. If some idiot back in the Sixties hadn’t barred him from traveling on the grounds that engaging with a hostile nation was forbidden, he would have been one of the international stars of the game. Fakhri and I were two sides of the same coin: father and son, as the rest of the group would joke. A resemblance that stemmed from our characters, and the stern countenances that sought to set the world at arm’s length. Two individuals from a now extinct stock who cared nothing for what went on around them: looking on and not getting involved. But I admit that Fakhri was an extreme case. I never fought for long and, full of regret for what I’d lost, would return to reality. He had lived his life without being prey, even for a moment, to such a feeling. He had seemed pitying when I informed him of my decision, and though I was careful to maintain our relationship and return to the old habits whenever time allowed, what had been broken was greater than any attempt to restore it.

A changeless backdrop. We bestowed but fleeting glances on the world. The glass blocked most of the sound, and what reached us did so purged of its degradation. If people only realized how beautiful they were when they shut their mouths. Fakhri had sat here for twenty years—every day except Fridays, which he would spend rambling about the city for hours, following this with a specially prepared meal and then bed. The walking cleared the cigarette smoke that clung to his lungs, and emptied his dreams of any unwonted words or deeds he had been forced to engage in. This was a program that admitted no outside participation; should it so happen—and it had happened many times—that he encounter one of the café’s customers, he would cut them dead without the slightest attempt to soften the blow. His acquaintances had grown accustomed to this. That the man should have maintained his solitary existence for all these years. Well, something must have affected his mind. Loneliness leaves you mad or a genius, and he oscillated between the two. But it seemed most probable, with the greater part of his life behind him, that madness was the closer. Maybe it was the Friday ritual alone that held his breakdown at bay.

I was a Trojan horse brought to life. I wasn’t sufficiently aware at the time to perceive that the virus first took root when I began to recount the stories that had suddenly unfurled before me out of a cave whose existence I had never guessed at. A gullible traitor, handing over the keys and only understanding what he was embarked on once his mission was at an end. I spoke with pride: what are we but a set of stories we tell or hear? And as I weakened before temptation, the crack in the window widened, and the street, with all its myriad details, slipped in to claim more territory for itself.

When did I first become aware of my betrayal? From the breadstick seller! That’s it! That half-turn, that look he gave me. Around five o’clock, quite unhurried, he would open the café door (one quarter wooden, the remainder glass), the rasp it made disturbing those present, who would plead with him to hurry it up, some waiting for that moment to test out newly minted wisecracks about the man’s lack of speed. The robe and headdress never changed. Maybe he had more than one outfit in the same faded hues, the same coarse fabric, the same length that granted sight of a skinny shank terminating in a vast and flattened foot trussed up in a peculiar kind of sandal that seemed to have been plaited from strips of a hide which had lost its color and whose original nature could not be guessed at. Similar strips were tied to the basket of breadsticks and roundels, passing across his chest while the basket itself swayed on his back. He’d lift these straps, the basket would lift over him and, as he turned with a dancer’s grace, would suddenly be in front. He would hold it, lower it to the ground, and set to: moving around the café’s tables, distributing his wares to the customers without a word being spoken. Not a day went by without my observing the whole performance. Before plunging in he would stand by the door for a few seconds, as though tallying up his enemies before the charge. Spellbinding, the slow pace at which he proceeded. It wasn’t frailty or weakness. It wasn’t age forcing him to keep that beat. He was healthy enough—you saw it in the rigid, upright body and the two sweating hands: it was just that he was like a man walking through a graveyard, taking care lest he wake the dead. A sinister rhythm that brought back fears I’d long discarded: of death and what comes after.

When the man was done, and everyone had taken their share of breadsticks, he would sit alone in a corner and sip the tea that Amm Sayyid brought him. Half an hour, then he’d set off again. He’d perfected all this an age ago, and every motion now took place according to a system and routine that none dared contemplate altering, each one of us operating in his private world, satisfied with his appointed station.

Ashraf al-Suweifi would watch the breadstick seller for the time it took him to close the door, then return to his papers, a stack comprising almost every sheet of print journalism that had ever been published. It was an assignment he had taken on sincerely and devotedly after completing his studies in the faculty of engineering. He’d gotten the message early on, but his father would continue to repeat the famous line in his hearing: “Finish your studies, and after that you’re free.”

Now Amm Sayyid’s voice rose up to puncture the tranquil calm, telling al-Suweifi of his discovery of a suspicious shortfall in the storeroom’s sugar supply, and making insinuations about his nemesis Fathi, who stood at the counter reckoning up the orders. Al-Suweifi had no liking for the particulars that Sayyid was obliged to share with him—the supplies running out, the number of cups they’d lost. He lacked his father’s ability to discuss work-related matters without getting dragged in. His response brought the conversation to an end.

“Please, Sayyid, don’t bother me with these silly things.”

And once Sayyid had withdrawn, thrilled with this further proof that his word held sway in the café, al-Suweifi let out an exasperated sigh:

“Haven’t I lost years enough to stupid trifles?”

The customers sympathized with his bitterness. They would attempt to soothe him by suggesting that they, too, had lost many years against their will. Most things in life were stupid trifles.

“God’ll make it up. Others have lost more.”

Anwar al-Waraqi would voice despair at his circumstances, and at the eons he’d spent in marital disputes, which had at times prevented him coming to the café—until the separation had set him free.

And what was it they did, to make them regret this lost time? The question preoccupied me, and the breadstick seller had sensed it, telling me, “You don’t belong here. . . .”

I spent nights plotting to get rid of him before he exposed me. I’d murder him in one of Shubra’s serene nighttime streets and around his body I’d spell out some devastating line of Mustafa’s—in breadsticks. The patrons dealt gravely with anything that concerned mixing with the outside world. A shared faith with no prior consultation and no proselytizing necessary.

Ashraf al-Suweifi had returned home, disgusted, from the faculty of engineering to find his father preparing to leave his office and take his siesta, a routine only altered in exceptional circumstances, irresistible circumstances before which one could only surrender to the rhythm of the outside world. For instance, that one’s son had fallen into a fresh trap.

The father had never protested his son’s absences. What was left to him in this world was too precious to waste in argument. In his private corner, which he would subsequently bequeath to his offspring, he had made use of every minute. He was not far from the window, but the daylight didn’t reach him and the passersby couldn’t see him: a miraculous spot, as though a giant creature were shielding him with its shadow. Of course, closer inspection was enough to solve the riddle: that corner was the beginning of a long, dark passage at the end of which lay a large room for storing the café’s supplies. The corridor’s shadow cast its full weight on the father’s corner to set the daylight, no matter how bright it became, at defiance. A space like this had to be used for the purpose it was made for, and he would sit in silence for hours, watching, his memory picking out millions of images for use in his report to the heavens on what went on down here. He was the founder of the League of Watchers, and the memory of him and his like had to be preserved.

When he passed from this world, his son immortalized him in one corner of his corner:

The al-Suweifi Museum for the Defiance of Death and Forgetting

To wit, a wooden cabinet containing his possessions: some books and old magazines, his spectacles, a tarboosh missing its tassel, an antique radio, and—at the heart of the display—a small statue by a long-forgotten artist, a patron of the café, notable for a Mona Lisa-like gaze of exaggerated effect. Such a distinctive feature in such a poor piece got on the nerves of the customers: it seemed to be observing their presence. Indeed, it started to affect them after they’d departed.

“It’s following me in my sleep.”

Before tributes turned into an endless orgy of satire at ‘Big Brother’s’ expense, al-Suweifi shifted the cabinet so that it was facing the street, explaining to his deceased father that since his gaze had always extended to the outside world, he could now continue doing what he had loved. All thought the idea a good one, avoiding the statue’s gaze as they walked past and reveling in the discomfort of the passersby.

The younger al-Suweifi inherited his father’s faith, but expressed through a different rite whose performance he never shirked; he scorned criticism till he had proved that it was not worldly concerns that interested him, unlike those professional perusers of newspapers and magazines who become machines that churn out information and analysis. Al-Suweifi never spoke of what he’d read. No explosions of irritation from him. The politics page, the crossword, the obituaries: the same calm, the same posture for each. No sooner finishing one paper than dropping it at his feet to start the next—without a pause: a grueling marathon.

I’d arrive at noon to find a respectably sized heap on the floor. If time was pressing, he’d speed up, adjusting his pace to a biological alarm clock that let him know when his next appointment was approaching. When not a single newspaper or magazine was left, and once the cuttings were pasted up on the wall, Amm Sayyid would wipe away the dirty trace of ink—of words—and set the backgammon and a ginger and cinnamon upon the table. The drink was the secret behind al-Suweifi’s unflagging energy, and with its arrival, unavoidably, the topic of women would be broached, the topic on which he would address us with any man who had experiences to share welcome to contribute his advice. Al-Suweifi’s friend would sit facing him in silence, not breaking the flow of talk, greeting none of us. He would open the board and arrange the pieces, taking white because al-Suweifi favored black. They were the only two exempted from the café’s rule forbidding all games but chess, embarking on their match with the shyness of someone taking what does not belong to them. Should enthusiasm get the better of them, al-Suweifi would apologize to the others who were sunk in thought:

“Sorry about that, your excellencies. It’s just that he will slap those pieces!”

His friend, who by some miracle we hadn’t yet poisoned, would point at al-Suweifi, intending to give an impression of superiority:

“A kid. What can you do?”

But it would rebound on him and leave him looking foolish.

Their racket did no harm in any case, for their stamina lasted no longer than a single round, after which they’d depart.

I always wanted to leave a card for those I visited, like Arsène Lupin, but with a different inscription for every home:

“To you, and your exquisite taste.”

“One day you’ll thank me for what I have done.”

Mustafa Ismail

The Book of Safety