Читать книгу The Book of Safety - Yasser Abdel Hafez - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Usually, nobody noticed me. I banked on it, and it was what I wanted: for the victim’s gaze to stay fixed on the man sat handsomely at the massive desk. Which was how all the accused brought in to us behaved, however alert they were—only seeing me when my superior, Nabil al-Adl, would point me out, at which juncture I would be forced to emerge from the shadows.

“Stay as you are, handmaiden to the truth.”

My preferred designation. He thought and I wrote. They wished me to be his hand and his pen. I was not to sit level with him, and when he walked I would be a step behind: a countrywoman trailing a husband as yet untouched by urban mores. And those who came here understood in advance, which was why they gave me not a single glance, their eyes fixed on the man who decided their fate and not the one who transcribed it. Transcription is merely the documentation of the final verdict, a cosmetic enactment. Yet Mustafa Ismail, former law professor and the man dubbed the most skilled thief of the 1990s, was aware of my presence from the very first. He gave a fleeting turn behind him to where I sat. Later, after I’d become captivated by his ideas, I would remain haunted by that turn, searching for its explanation.

Truthfully, though, neither I nor my profession were quite so inconsequential. What can I call it? False modesty? A deep-seated desire to draw back from the limelight? Some blend of the two blinded me to the potential of a unique position which I never made use of as I should. Another sufficiently rebellious character might have published secrets the likes of which you’ve never dreamed. Mustafa, looking to immortalize his tale, realized this, and in me he found his messenger.

Maybe it was for this reason that I had responded to the strange advertisement stuck up on the wall of the café and had set out to claim the role that seemed written with me in mind. During my time in the job, a limitless sensation of power mounted inside me. I would overhear regular citizens discussing the big issues of the moment, each taking a stand and staunchly defending it as they advanced their conclusions and proofs; yet the truth is always different from the way things seem, and I was one of the few allowed to know it—though I couldn’t let them in on what I knew, bound to silence without being ordered, in keeping with the customs of all those who came to the Palace of Confessions. Yet it suited me; secrecy did not vex me. The power was quite enough: the growing self-confidence that compelled those around me to approach with caution, as though I were a modest godling come down to walk among them.

My initial assumptions about Mustafa’s intentions were blown away by his confessions. He didn’t want me to immortalize his story, as I’d imagined. He didn’t care. This much seemed clear from what he said:

They lie who say that a man’s life story is all he leaves behind. They set us in motion with profound utterances that fix themselves in our thoughts, and we move accordingly, like machines with no minds of their own. You are the totality of the actions you undertake now, in the moment, and when you pass on that space you filled is taken by the breeze. Actions are fated to be forgotten, and the history books never pay attention to what you had intended they should. They see what they want to see: a beautiful woman who gazes your way, but her heart and mind don’t see you. Don’t act the fool by troubling yourself with immortality.

*

He was doing as he pleased, as though he were still free as a bird, one more soldier enlisted, just as he’d picked out his chosen men before: a nod of the head to make them instruments of his will, awaiting orders and a time to carry them out. I was one of the chosen. He saved me from research in the bookstacks, from concocting patchwork theories snipped from dozens of different books—criminal motive, the behavior of the masses in the absence of a unifying objective, the resentment of the poor as a driver for human history. He saved me from playing an unsatisfactory role.

“Not useful.”

Thus Nabil al-Adl, my terror of whom—or of what he represented—I had spent the first part of my training battling to master. The softest manifestation of the state’s power, the sort whose thoughts and plans lie beyond your power to guess at.

“Well, maybe useful, but you have to hitch it to reality. We’re not a research center—in part perhaps, but we have other facets you will have to experience for yourself.”

Mustafa helped me discover these facets. He vouchsafed me passage to the other shore, from enemy to ally, and all I had to do was wait to be told the details of my mission.

We knew about him before he arrived, from old files in the archive, but ordinarily we wouldn’t place much faith in them. We knew how they were written. As al-Adl sighed:

“Torture, fabrication, and filth.”

But nor was he much impressed with what I gave him, selecting from my report only the most obvious passages, those whose meaning was plain. I had written:

What Mustafa Ismail and his associates achieved evokes both a legend and a scientific fact. The legend is that of the Merry Men who banded around Robin Hood, and associated with this legend is a scientific fact, to wit: psychologically and physically, men require an activity that might theoretically be beyond their capabilities. This ‘merry’ part of man, this ribaldry, must be sated, which explains why, for instance, the male prefers war over dialogue. Castrated by civilization, this aspect of his nature may find its outlet in addiction—to sex, to sport, to drink—but others can only fill the void by engaging in a rebellion that liberates them from authority.

My superior described what I presented to him as ‘a sentimental report.’

And although in a professional context the phrase was meant harshly, it pleased me. Perfect as a cryptic title for a book. Perhaps I’d use it, would agree to the terms offered by Anwar al-Waraqi, owner of a printing press who was seeking to rise a rung on the ladder of his trade and take on the title of publisher. He thought the stories I told him about what went on in the Palace of Confessions would make a good book, showing how things really got done in this country.

“And anyway, brother,” he’d said, “it’s a chance for us to get out of here! See the world a bit before we die.”

I would make al-Adl a character, would overstep the bounds and write his name. Who would ever believe that Nabil al-Adl was flesh and blood, and genuinely occupied a position of such sensitivity? Who would ever know but members of the club, the cream of the crop? Who would ever credit that these things were real? Regardless of risk, there was no way such an artistically satisfying character could be allowed to slip through my hands. He had all the qualities to ensure the book’s success: his blind devotion to traditional values, his passion for (enslavement to) the ringing lines whose phrases, no sooner uttered, burrowed themselves inside my mind as though I was being mesmerized. Could he ever have allowed himself to sacrifice his fine-sounding ‘torture, fabrication, and filth,’ and cast around for something more in keeping with my sentimental report?

I may say that I knew him; I worked with him for five years. It was he who chose me. An official in his position has the right to choose his assistant.

*

The wording of the advertisement, torn from a newspaper, had forced me to stop and read it through:

In your own hand, write the story of your life as you see it in 300 words. You may use any literary style or approach to convey your message. Send the document in a sealed envelope to the address provided, writing below the address: c/o THE OFFICIAL RESPONSIBLE FOR THE ‘TO WHOEVER WISHES TO KNOW ME’ COMPETITION. We will be in touch.

And with that, I sent off the necessary, without the faintest idea who was behind the advertisement or what they might want with the applicants. Subsequently, I would learn to my astonishment that thirty letters had been chosen from thousands upon thousands of submissions. Let’s think clearly here: do you, as I did, send your life story to an unknown address for an unknown purpose unless you are ready and waiting to entertain a mystery? The days go by, but your enthusiasm remains undimmed. You keep your senses sharp lest the call go unheeded. And when it comes, it’s to reveal this farce: I’d always thought myself different from other people, and had made sure to keep clear of them, but I was now to find that thousands of them had had the same idea, and had been waiting to be summoned as I was!

The thirty were soon whittled down to five. Someone came along to look over the queue standing outside the door. Three years later, this person would be me. I came straight from home and joined a crowd of about forty souls all hoping to get their hands on the prize, pretending to be one of them. For exactly two hours, instinct guiding my judgment, I struck up conversation. I provoked, played on nerves: one of many tests to determine the five who would be chosen.

The final test, briefly stated, was that each of us rewrite his life story from the beginning, not necessarily with the selfsame words and sentiments we’d sent off in our letters, but any way that took our fancy—just for purposes of comparison and to make sure that our first efforts hadn’t been plagiarized or written for us by others. One of us withdrew for a reason we never had explained to us, though it was clear enough: he had no story to call his own.

I wrote:

The first time I mourned anyone was at the death of Fahmi, son of al-Sayyid Ahmed Abdel-Jawwad, and the first time I felt fear was when I read about Gregor Samsa’s metamorphosis. Awaking to find that you’re an insect, and must now deal with the world on that basis, and because you know the world has no logic, and that stories are truer than reality. Then all things are possible, even things as nightmarish as this. Then The New York Trilogy showed me that meanings are tangled together and confused to an extraordinary degree, and that most likely nothing has any value. That is how I might describe my life: from one book to another, from one story to the next. I could list dozens—no, hundreds—of works, but this is not what you’re after. You want to know what happened to me in real life. Only, unfortunately, I have done nothing worth mentioning to date. Of course, I engage in the quotidian activities that keep me alive; it’s just that now, approaching thirty, I cannot think of anything worth telling. The dilemma may have its root in my attitude. There are those who can turn the simplest incident into a dramatic happening worthy of the world stage, but it is my belief that certain conditions need to be met before adventure can claim the name, that there are conditions that make a life fit to be written down. The power to breathe, and speak, and mate is not enough to make your tale worth telling.

This, in short, is my story, which you asked for; and, as you can see, it is finished inside your limit of three hundred words. And because I believe this limit has to matter to you—it was the only condition you mentioned, after all—I shall add the following: my way of thinking is liable to lead to nervous collapse, but what spares me is that Florentino Ariza is my favorite protagonist. Like me, he spends his time engaged in trivial things, waiting for his one ambition to be realized: to be reunited with his sweetheart. A lucky man, who gets what he wants.

After we had passed through a battery of tests, they gathered us together in a large room. We’d no idea what to expect and hadn’t dared ask. Not a sound. None of the usual chatter between office workers. No doors opening and closing. The person who’d escorted us to the room hadn’t uttered a single syllable. We had climbed from the ground floor to the third, then down a long corridor, and our guide had pointed to the far end of it and walked off. A room, empty but for five chairs.

I hadn’t been able to get a precise fix on al-Adl’s age; his features were so bland that it was difficult to form impressions. He inspected us, our files between his hands, then spoke two words, no more—“Khaled Mamoun”—before turning to exit the room, leaving the door open. I went out after him and shut the door behind me, making sure it did not slam. I fancied that there was a smile on his face. His guess had been on the money, his instinct true: he had picked out an obedient helper who required but few words to do what was asked of him.

The next day, I received a plastic card, blank but for my name. No logo, no phone number, no job description, just, in its center, engraved in black: Khaled Mamoun. The first of the avatars of a mystery which I must accept without question. No one ever brought it up. They acted as though everything were completely normal. I couldn’t tell: was this deliberate disregard or was it stupidity? Was it, indeed, the long habituation that leaves the strange familiar? Would a time come when I would cease to be brought up short by the thought of my existence within an institution unlisted as part of the state establishment, headquartered on a patch of wasteland, and ringed by a wall shielding the mounds of sand we were forbidden to approach?

But perhaps I was overdoing the astonishment. What did I know of the world, anyway? Other eras have played host to dinosaurs the size of buildings, and seas that part to swallow kings. What’s one more wonder? Why did I obsess over peripheral details and miss what my coworker Abdel-Qawi called ‘the crucial point’:

“Why can’t you just accept that we’re as high as it gets—the agency that only takes on the most critical and sensitive cases?”

Logically speaking, I agreed with him, but one thing stood between me and acceptance:

“But whose agency?”

An exasperated sigh, then he would pull himself together, invoking the patience of a father confronted with an offspring’s mulishness, a father who believes such patience is the way to ensure that his son learns all there is to know:

“Just so you’ll stop pestering me, then. We are an agency tasked with looking into and keeping tabs on everything—on whose behalf I couldn’t say for sure, but what’s certain is that we are on the side of good against evil. Not that I’m bothered myself, but I’m telling you to help you get past this silly muddle you’re in. Why do you ask questions that can’t help you? This place has been around forever, as far as I know. It’s a miracle we were chosen. And quite honestly I reckon you’re asking the wrong thing. Instead of ‘What’s our job?,’ ask yourself ‘How am I doing?’”

A pointed observation, and one I had heard on numerous occasions. He would repeat it robotically.

It was either that, in the instant he was made, air had outweighed the other elements in his body, or that he was able to manipulate this balance for his own purposes. He moved just like it, light and quick. His presence took me unawares: I would hear neither door opening nor the sound of footsteps. He had a physical slightness at odds with his morbid craving for food. After he had departed my life, a caricature of the man lived on in my mind: using a chicken bone to write or comb his hair, outfits accessorized with vegetables—a collection of contradictions called Abdel-Qawi. For all the settled calm with which he was endowed and which imbued his features, he was the most trying person I have ever met, flitting without warning from mood to mood. He would decide to speak and it would be impossible to interrupt him: loud tones to make his point, frequently lapsing into silence midway through his inexhaustible stock of stories for the air to fall still once more. Before we bonded, this behavior had incapacitated me. This reaction of mine astonished him, and he regarded it as evidence of an unhealthy absentmindedness—or worse, a disregard for others. And, as always with him, what he believed was not up for discussion.

I couldn’t make up my mind which position best suited him. Uncategorizable in a place whose function was to categorize and judge. Which is why I left and he stayed on. His experience enabled him to sidestep the difficult question. Commenting on his behavior, I once told him, “We are obliged to be serious.”

And he replied, with a simplicity that defeated my assertion, “Says who?”

Is this why everybody loved him?

We got caught up in a friendship, ignoring, like teenagers, our lack of anything in common. With the self-centeredness of someone on a voyage of discovery, I didn’t care; I needed a guide through the initial stages, and for the duration of that period there was nothing I hid from him, with the exception of the fact that I was writing down everything that happened.

I was, as they say, swept away: bewitched by his regional dialect and the childlike laughter that vied with his constant chatter, and obsessed with the riddles he left dangling over my head.

“They called me today from Alexandria. Try and guess what’s happened.”

I had no way of knowing who ‘they’ might be, but I had learned not to ask, because he would manage to sidestep my inquiries by deploying one or other of his extraordinary stratagems. Family, I guessed, his relationship to them reduced to financial assistance. But as I grew closer to my other colleagues, the mystery surrounding Abdel-Qawi—his roots and family—only deepened. The way he spoke about Alexandria gave the impression he’d lived there as baby and boy, but the occasional southern phrase left the connection he sought to imply open to question. Everyone had a different story for him, which they’d swear to as if they’d know him since childhood—one of the entertainments of our Palace, built as it was on secrets and paradox. Stories from the world of hackneyed melodrama: on the run from a blood debt unavenged; no, his family had been killed in mysterious circumstances; no, they hadn’t been killed and there was no blood debt, either. It was simpler than that: he dumped them in order to live as he pleased. A family of exaggerated indigence, vast in number. A father whose favored pursuit was screwing his wife, siring seven more besides our man. Should Abdel-Qawi shoulder another man’s burden? Even nobility has its limits—and to describe him as cowardly just because he took a pragmatic view would hardly be fair. The long and short of it: he saves himself or they take him with them. And what good would that do?

People loved him, and they cared about him, and whenever he disappeared—on a mission or for personal reasons—our institution lost its soul. Even so, I found someone leaning in with a word of warning:

“Watch out for that one.”

One sentence sufficient for fear of him to meld with my friendship; for everything he did to take on an aura of awe and respect. Yet I was not wary. I represented no threat to anyone, him least of all. I played the part of someone passing through, and placed myself outside the fight. What I genuinely feared was the terrifying emptiness that surrounded him and into which he dragged anyone who associated with him: no history, no present, and no future—just the moment in which he was. And when he withdrew, it was like he’d never been.

After the curtain had come down, and while the players were bowing to the audience, it seemed to me suddenly as though the five years in which I’d known him had been a mirage. I would walk for hours and suddenly come to, almost out of my mind, without a single fixed memory—each frame erased before it could be linked up to the next. And not just memories of him, but of everything he touched, everyone who’d shaken hands with him, everyone to whom I’d told his story. Had it happened, or was it just a flight of fancy drawn out longer than was proper?

Does prison guarantee that your sins will be paid off? When we step outside the law, does this mean we have a debt toward society that we must pay? And why does the regime, too, not pay its debt toward society? Why is it not held to account as we are?

These are questions it is imperative to answer before undertaking any act of rebellion. Your conviction that you are in the right will grant you an incredible freedom of thought, such as you never dreamed you possessed, and will assist you in planning every detail—starting with selecting your victim, and by no means ending with how to emerge intact from various desperate situations and dead ends.

Mustafa Ismail

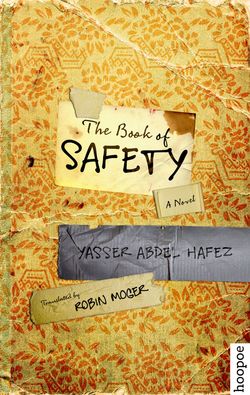

The Book of Safety