Читать книгу The Book of Safety - Yasser Abdel Hafez - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

I slowed, wanting to see the mechanism complete the operation, but fear of failure spurred me to throw my body through the narrowing gap. I didn’t calculate whether it was wide enough or not, whether it would crush me, or chop me in two, or maybe give free rein to its cruelty and sever a foot, leaving me to live out a life dragging what was left of me along the highways and byways.

God in His mercy was watching over me, and I made it through in one piece. I dropped into emptiness, then water detonated, as I broke my fall in a pond filled with plants. I cared nothing for myself: all my senses were trained on the giant petals folding shut. I had observed them many a time from the desert sands, and this was the one and only occasion that I would have the opportunity to be a part of their structure. The gap admitting light thinned gradually till I was lost in an endless darkness, stretched out on my back in a watery grave, no torch to hand. It had been a spur-of-the-moment decision to jump in. The perfect symmetry of the outer shell had overwhelmed me and, distracted by it, the chance had nearly passed me by. The sun had been setting and with the last of its rays, the sound of machinery had begun to swell, and the golden petals had risen up. Here I could search for a different starting point for myself, something other than my own mad project, returning home to live in harmony with my quotidian routines.

Before regret could come, a sign that I was on the right path: a dazzling white light that pushed back against the pitch dark; hundreds of small creatures flitting by so fast I could not immediately tell what they were, but my heart was glad. Even if they turned out to be carnivorous and tore the flesh from my bones, I’d consider their pricks a prize that I had earned. The lotus leaves onto which I’d fallen were struggling to shake off my weight. It was like they were cradling me. A comforting thought, though I leapt up in alarm when it occurred to me that they, too, were closing as their larger iterations had before them.

The water soaked me through. I was being purified that I might deserve this honor. On down a narrow corridor, built wide enough for one. All the space on offer had been given over to plants, in shapes and colors I hadn’t known existed: blue, red, white, and gold, some with elongated leaves, others with leaves round and flattened, some with beating hearts, some coyly folded, some gazing out with brazen hunger.

Never would I have guessed that Amgad al-Douqli, owner of the Lotus House, was quite this crazy. A jamboree so carefully coordinated that no one element overwhelmed another and then, as the space widened, it became clear that it would be impossible to take in the scene in its entirety. Luminous larvae lent an air of magic and mystery. They squirmed around me, investigating the creature who had invaded their sanctuary, and turning me into something sacred. The profane was non-existent. We shall spend the night alone together, glowing friends.

The living quarters were tiny. Al-Douqli had wanted a lotus plant to enclose him like a womb, but he couldn’t get one large enough. Forced to build, he’d drawn inspiration from the idea of a Buddha’s statue and had erected a house, just a bedroom and bathroom on a base constructed from lotus leaves. The end result was a giant and sinister lotus that closed tight shut, with no way to make it open other than the dawning sun.

My dear Amgad al-Douqli,

I shall not write at length, for we share no bond by which I might compel you to endure the companionship of my thoughts. I wanted to write to you simply because of this wondrous home of yours, the target I selected as the starting point in a new life, whose essence shall be movement rather than immobility. All I have learned and trust in shall be put to the test. There is no need for me to stress that I am a decent man and not a thieving crook. Not yet. And certainly you will know that a man’s proximity to decency has nothing to do with the trade he plies. I have no doubt that you will guess what kind of person I am from the way I phrase this letter, but I am not obliged to explicate and explain. We are not friends, in any case, though I am currently sitting at your desk and using your paper and pen.

Permit me to express my admiration of your genius in designing this house and its garden. This genius was what summoned me, insistently, to view it up close.

You will find nothing missing. The safe is untouched. I haven’t looked in any potential hiding places for money or jewelry. That is not why I came. I do not know if this will cushion the blow of having your home invaded, but, whatever the case, I would like to inform you of the following: to me, your house is nothing but a station on the way, a door from one world to another. All I have permitted myself to take is a picture of you with a young woman who, I happen to know, is not your wife. Consider it a down payment on a friendship that may one day bloom. And so I might set your heart at ease, be certain that the picture will occupy the most prominent place on the wall of my modest home, as though it depicted my own brother.

Accept my thanks and appreciation for your understanding, which I regard as an unavoidable necessity.

Your devoted servant,

Mustafa Ismail

Anwar al-Waraqi lifted his eyes from the page. He stayed staring at me, and I didn’t care for it. I don’t believe in what they call the language of the eyes—what was said on the subject I had always considered misguided hyperbole. Nevertheless, I held firm; if this was a test, I wouldn’t turn tail. I tried amplifying my inner thoughts and transmitting them through my gaze:

You’re a fool.

And you’re full of it.

He broke off eye contact to confirm—as though he were a real publisher and not a mere printer—that this beginning left him unimpressed.

“Doesn’t work,” he said. “The flights of fancy don’t fit with the real story.”

Anger at what I took to be an insult was tempered by a suspicion that he might be right. I had been led on, bewitched by the possibility that such sorcery could be real. Even so, Mustafa’s first rule had to be defended:

You are always right. You are sacred. You must believe this before making your move, the vital first step to making your miracle a reality. Within us all, alongside what might be described as the fleetingly mortal, is something more elevated, and to lay your hands on this thing entails being transported to a higher plane than those around you.

So affecting was the idea that my voice grew fervent, silencing the voice of reason, of doubt.

“I didn’t believe the Lotus House existed,” I said, “and al-Adl strengthened my doubts—he had no time for wonders and marvels. He put it down to Mustafa losing his grip on reality, to him confusing fact and fantasy. He would gloatingly declare that Mustafa’s mind couldn’t cope with the perversity of his thoughts. He asked me to look into his claims and redraw that missing boundary line, which is why he never bothered looking for Amgad al-Douqli. However, I believed that the truth of Mustafa’s tale, its entire value, rested on al-Douqli and his hideout in the heart of the desert—it was the key to the man—and so I began my private quest to locate it.”

“And?”

We were in a Chinese restaurant in Cairo’s Heliopolis district, empty but for us. It was a boast of al-Waraqi’s that he knew somewhere to go on every street in Heliopolis. He was talking of how his father had had the opportunity to upgrade his business activities and the lives of his children. He’d been offered a printing press for a trifling sum in the Seventies, but hadn’t wanted to leave Shubra.

“Shubra’s the sea and I’m a fish,” he had said. “I could never leave.”

Al-Waraqi never tired of sighing over the chance let slip.

“I could have been something else altogether, God forgive him. A fish! What a metaphor, I ask you. . . . The Abdel-Nasser generation drove him out of his senses.”

“Topographically speaking, you’d have trouble comparing Shubra to the sea. Maybe you’ve noticed how its streets all run south to north. I mean, it’s more accurate to compare it to a river.”

He knocked back what was left in his wine glass and rode roughshod over what I’d said, as though he hadn’t heard, ordering another bottle from the young waiter leaning over him.

The rice: lost in its own dazzling whiteness.

“They steam it. Very healthy.”

Given the way he gobbled it down, ‘healthy’ seemed like a stretch. His presence was at odds with everything about the restaurant, down to the smallest detail: the staff with their contrived air of politeness, the pair of scrupulously carved red dragons, the color scheme of vivid but inoffensive crimson and yellow, the soft music pitched for murmuring patrons. I was suddenly struck by revulsion at what he stood for, his hopes and dreams of social elevation. I still hadn’t learned to read a letter before opening it. As Ustaz Fakhri had once advised me, justifying his driving a café regular from his chair:

“Never expect good things from a man whose smile never leaves his lips.”

An odd reason to commit an unkindness against someone who seemed civil enough, but seated with al-Waraqi I longed to be able to love and hate based on motives like these. I waited for Dutch courage to come, but wine is the same as masturbation: the illusion of ecstasy, then the letdown.

*

Even going out into the desert with Amgad al-Douqli and his driver, my doubts accompanied me. The Saqqara pyramid was the last thing I could make out. After that, it was all desert with no landmarks to tell one part from the next. Yet the dark-skinned driver, his master’s equal in decrepitude, drove the powerful, fitted-out car with the self-confident prescience of Zarqa, blue-eyed sibyl of ancient Nejd, and did not give in to my attempts to draw him out of his silence. He slid in a cassette at al-Douqli’s request, a ponderous symphony by Haydn with no choral parts. It was among the most beautiful pieces the Santa Cecilia Orchestra had ever played, he said, and I was lucky: his son had sent it to him just yesterday from England, where he lived. Enkland—he pronounced it as the Arabs did, with the ‘k,’ and made it sound like a country he had been the first to discover. The melancholy music and the vast tan expanse around us woke within me an obscure fear. Maybe I was getting involved in something I lacked the ability to deal with. What if he was Mustafa’s partner, and the Lotus House a warehouse for their ill-gotten gains and a tomb for the curious?

Eyes closed, he nodded his head faintly in time. He appeared to have nothing to do with crime, but my work had taught me that those who seem furthest from it are often the closest. Mustafa again:

The one you discount is precisely the one you’re after.

If he decided to murder me, then nobody would find out what had become of me, and who would care? Or notice? Huda might have tried if I’d shown her a little love, but her limited intelligence would make her of no use. Her search would stop at the little gang in the café, who’d persuade her that each of us has a journey that he or she must make.

I distracted myself from the fear by indulging my despair at a loneliness more profound than that of Fakhri. His choices in life (though I mocked them) had at least, I now decided, been made of his own free will, and were not guided by the will of others as mine were.

Most of what Mustafa had said was true. From afar, the flower appeared vast and golden, the sunlight reflecting off its petals and burning like a shard of fire. A lair for indulging lusts or the symbol of some secret cult. Having opened the iron gate for us and let the massive chain drop with a clang, the driver returned to the vehicle. Al-Douqli ordered him to stay there, saying that we wouldn’t be long—an order that inflamed my curiosity.

We had to duck to pass through a little door which was initially impossible to make out. Al-Douqli let me enter first so that I could help him through. To conceive of a place like this, set out here in the lifeless wastes, would have been impossible. Bewitched by the sight, my mind drifted and I failed to notice the crutch held out for me to grasp. Al-Douqli was forced to shout, poor fellow. We wandered about for a few minutes while he explained to me about the machine that managed the irrigation: pipes, reaching out underground to a subterranean reservoir, supplied the plants with the water they required at prescribed times. It was a system set up to run for years without need of human intervention.

“The only problem is that it’s going to turn into a jungle.”

And in something phrased close to an apology, as he clipped the leaves of plants that had spilled over the lip of their planter and onto the ground, he added, “The whole thing’s starting to wear me down.”

Did the house close up on itself at sunset and reopen in the morning? Were there glowing larvae? He laughed for a long time when I asked him, but gave no answer, leading me to believe that at night some miracle took place which no one but Mustafa had seen.

Anwar al-Waraqi tipped what was left of the wine into our glasses, moving the bottle back and forth between them in an attempt to serve us equal measures. He showed excessive interest in the final drop, which stubbornly refused to fall into his glass. He didn’t want what he was about to say to come across as an order.

“No getting around it, things happen in real life that are hard to believe. Just days ago, I saw a djinn leaving a girl’s body. I don’t mean the usual cliché, that she started speaking in tongues—I mean exactly what I say: after the sheikh had held negotiations to convince the demon to set her free, her body lurched upright and out stepped this weird figure. Just like us, but somehow see-through.”

He laughed.

“The spitting image of your friend Fakhri. An extraordinary resemblance! So similar that I thought the fellow who sits with us at the café must be a djinn himself. No way could that be a man. You won’t believe me, but at the same time you must understand that people no longer believe in fiction and they don’t value it. Aren’t you literary types always saying that reality’s now stranger than fiction? So make do with reality. All I ask is that you amend the introduction so it’s in keeping with what people expect from a book like this. After that, you write what you want.”

Getting the timing right is the most important step in the whole operation. The plan can be perfect, the victim ideal, and then the timing ruins everything.

Though the issue of timing can never be inflexible, there are rules on which one can base one’s calculations, at least most of the time.

The best time during the working week: between ten a.m. and twelve noon (when attendance for public and private employment is at its height).

The best season: winter.

The best day: Friday in summer.

Mustafa Ismail

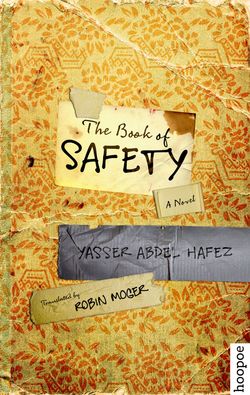

The Book of Safety