Читать книгу The Book of Safety - Yasser Abdel Hafez - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

Do what you have to.

An almost meaningless line, one that belongs on paper, in the pages of some novel or movie: a thriller’s hero addressing his sidekick in Delphic terms, an indirect order to kill, to burn all the files.

Nothing to be proud of that this fantastic sentence is my father’s legacy to me. No money, no memories, nothing but five words bequeathed to my mother, a woman no less peculiar than him. She considered them a message to me, one that I had to memorize, and from childhood on she drilled them into me, enunciating in a classical Arabic appropriate to a man who had dedicated his life to the love of poetry and the Arabic language, yet ill-befitting a witless woman who apprehended life through instinct alone.

And yet, after a journey that has lasted long enough, I find that I am proud of what I inherited and, like my father before me, I shall, unless I find someone stronger, pass it on to my daughter Hasna. I shall not leave her to live her life with no wise words to light her way in times of need.

At the time, I paid no particular attention to this part of Mustafa’s confession. As far as I was concerned, it had no bearing at all on the overall story. That people have children is only natural. That they have Hasna, whom I would come to know, is not. Had Mustafa spoken more about her, perhaps I would have had the information I needed to be able to deal with her; and perhaps if I’d sought her out back then, much would have changed in the approach I took to my book about her father. But I let the chance slip. After getting to know her, I went back to the case files, but in all I’d written I could find nothing about her save her name.

I was drawn to Mustafa and his grand style:

My father died when I was nine. Nothing of him remains except a single, terrible scene: I stand beside my mother, leaning against the wall that has been hastily thrown up across the entrance to the houses as part of the protection measures ordered by the army. He waves farewell to us, but the sun is glinting off the medals that adorn his uniform; it flashes into my eyes and I do not see him. Off he went to turn back the Tripartite Aggression, and nothing now remains of him save that glare and an open-topped truck that whisked the dust up in our faces. He left me in the care of the fool he had married to score the double: God’s favor and a young body he could enjoy as he pleased without the domestic give-and-take that comes with an equal match. This was common knowledge in the neighborhood where I was raised, and as I grew older I learned of it, too. I would hear it alluded to at all manner of events and occasions. The first time I heard my circumstances so described was at the conclusion of a boyhood squabble over the result of a football match. We had disputed a goal with the opposition. They said that the ball had passed inside the post of piled bricks, and we insisted on our view, while the referee—because he was the least physically robust of us all—stated that the incident had taken place some distance from him and so he was unable to say one way or the other. As captain, I was obliged to stand fast and defy. A member of the opposition shouted in anger:

“Son of a retarded bitch, just shut up, you don’t understand anything!”

When the time is right, the meaning of my father’s counsel glitters like a jewel. The lot of the one who insulted my mother was a rock to the head. His blood flowed as he fled, screaming out the second truth:

“You really are a bastard!”

Would you care to know everything about my past, or just glimpses? Shall I tell it to you as an entertaining story, leaving you with nothing but the pleasure of its telling, or would you prefer it served up with what it betokens? If so, you will have to shoulder some of the pain that accompanied the tale’s unfolding. What do you want? The burden of choice falls on you, and you alone must bear its consequences.

This question leads us to another. My apologies. Bear with me. One’s life, if you weren’t already aware, is a chain of question and exclamation marks all linked together; summon one and the rest snowball after. And so: would you like the story from the beginning or the end? I can tell it both ways, with my assurance that no errors will creep in. I ask, because there are those who only like to look at the end once events have unfolded. These individuals are blessed with a great deal of childlike naiveté, which leads them to resent the flashback—not just because it spoils the pleasure of surprise, but because it forces you to use your mind, to become an active participant, anticipating events according to the end that you have glimpsed. The flashback is the desire to intervene in the divine plan.

Would you like to know your end, then arrange your life accordingly?

This question was the true beginning of my relationship with Mustafa Ismail. I had heard dozens of confessions, and none had affected me as his did. One might reel me in with its romanticism, another with its violence, but neither would be more than a story—transcribed professionally and as tantalizingly as possible, yet dead. Soulless.

The records stated that he was over fifty, but his face and body paid no heed to the records. Powerfully built, he was possessed of a considerable charisma which stemmed from an unfeigned gravity of manner. Like the heroes of legend, something in his expression gave the impression of a deep-rooted grief, and in the very instant of our meeting I realized that the descriptions of facial features which are always attributed to these heroes were no laziness on the part of scribes, as I’d assumed, but rather that faces are shaped by the roles appointed them.

Nabil al-Adl treated the question as he did the majority of Mustafa’s confidences: as blasphemous, and a cunning attempt to divert us from the case by turning it into a debate over fundamentals.

“And anyway, what end?” al-Adl asked, reading through my transcript. “Death? The final reckoning? Eternal repose? Getting pensioned off, perhaps? Divorce? They’re all ends. Which one does His Lordship mean?”

“You’re right.”

I whispered the words with a lack of conviction not lost on him. Ever since I had started looking through the case files in order to draw up the guidance report that would help us deal with him, a special bond had developed between Mustafa and myself. I have a talent for discovering other people’s weaknesses. I could hand Nabil al-Adl the shortcut to the character of whoever was brought before him, so that he might extract what information he needed without effort—but confronted by Mustafa’s personality, I found myself baffled. He seemed exemplary.

“It’s good that you believe him, in any case. It adds some balance to the case. But I would like to draw your attention to something: you have to draw a line between yourself and those we deal with. Never forget whose side you’re on.”

Another stern warning from the chief. In recent times, I had heard more than one warning, and this had been the roughest. I was aware that I was on the verge of severing my links to the place and to its laws, but I had nothing to dissuade me from this course. Al-Adl would never understand that anyone capable of framing a question like Mustafa’s has the strength to make it a reality. I understood; and I understood, too, that I would not be granted the opportunity to get Mustafa’s response. We would not be friends or partners. I must be content with my role; and yet I set down his words ashamed that I was cast in the role of his enemy. It is the case that if we do not possess the courage to evaluate our selves and place them in the setting they long for, the world will toy with us and make itself a farce.

*

Behind the children’s park was my place of work. A place unknown and unvisited by all but those fated to embark on a most unique experience.

The Palace of Confessions.

My private name for it, telling myself, as the microbus conveyed me from Shubra in the city’s center to the furthest inhabited spot in the eastern suburb of Medinat Nasr, Khaled’s off to the Palace of Confessions to have some fun.

The spacious park lay between the Palace of Confessions and a modest huddle of residential buildings, the greater part of it fringing a vast area ringed by a dull gray wall. No buildings could be seen behind the wall, only hillocks of sand, and it was topped by signs warning against approaching and taking pictures. From here, the park narrowed, terminating at a path wide enough for two to walk abreast and lined by cacti. When the employees all arrived at the same time, they were obliged to form a queue beside the cacti, one plant per employee. The door would only admit one person at a time—after the security device had checked their ID and allowed them in—but the throng I’m picturing never came to pass, not once, perhaps because there weren’t that many employees to begin with, or perhaps because I would arrive late, choosing to linger in the park, to take time out amid the dazzling hues of its flowers and plants—so captivated, indeed, that I was increasingly convinced that Chagall himself had arranged them, the only person capable of playing with color thus, of combining it to bring such joy to the heart of those who saw it.

Yet, for some reason, this joy was absent in the children there, their numbers never rising or falling; they seemed distracted in a way quite at odds with my assumptions about childhood. I’ve no experience with children, but generally speaking, shouldn’t they seem joyous and uninhibited? These ones weren’t like that. They played with a busy discipline that made it appear as though they’d been drilled. One would come down the high slide, then turn and pad back to its ladder, waiting his turn like an adult who has learned that the system is the way to get what he wants. No shouting. No fighting over toys. I memorized their faces. No names. I never got to know them, because the mothers on the wooden benches never called them. Not one ever shouted for her child to take care, or dashed wildly toward their fallen offspring. They sat there contentedly, in their faces the placidity that comes from certainty. Women in their thirties and forties, elegant in the beauty-free way of wealthy women from Medinat Nasr, immersed in hobbies from their mothers’ era: three or four crocheting, a similar number flipping through fashion mags, while a lone blonde, younger than the rest, sang outside the flock and read books with old covers. Most likely their husbands worked behind the dull gray wall, pursuing mysterious callings in nameless buildings, or else were colleagues of mine I hadn’t met.

The ground floor of the Palace comprised a reception room where an ancient functionary passed his time solving crossword puzzles. My relationship with him lasted the seconds it took for my bag to pass through the scanner. I’d greet him and he’d pay me no mind. He couldn’t even see those passing him by. He’d been programmed along with the machine—and provided the row of lights on top didn’t turn red and its tiresome siren didn’t sound, he had no cause to lift his gaze. I was tempted to put a knife in the bag so his scanner would scream and he’d be forced to notice me.

The old man was the lobby’s center, surrounded by four flights of stairs, each running up to a different department, and behind his desk a flight down to the basement where the guilty were housed: comfortable little cells, tidied and searched each morning while their occupants took breakfast in the small cafeteria next to the games room. They were free to move between their cells, the games room, and the café. There was no fixed schedule and no locked doors, but the basement was their world until the interrogation was over.

*

Mustafa brought us a fearsome list of his victims: ministers, diplomats, artists, religious leaders, businessmen; people and crimes for which he provided the proof, the individuals concerned having preferred to make no report out of embarrassment or the desire to avoid scandal. Who would welcome detailed discussion of what went on in his bedroom? Who could ignore the many warnings designed to stop him telling? Documents vanished, and it was best not to bring it up. Private pictures of husband or wife, carefully concealed from the spouse, now laid out before sensitive eyes; the hidden revealed. Threats whose attendant instructions it was impossible not to obey. Nabil al-Adl himself had gone against his own creeds and convictions in order to keep hidden the photograph of his sister-in-law, Sawsan al-Kashef—near-naked and sprawled in her lover’s arms—which had confronted him one day, and written beneath it in fiery red ink, a warning: Don’t squeal.

What frightened the authorities, and got Mustafa’s file referred to the highest levels, was not simply that his victims included names whose homes were fiercely guarded around the clock. More pertinently, one of these names, the major general whose apartment Mustafa had been robbing when apprehended, headed a team responsible for updating strategic plans for guarding the president himself—a fact itself outmatched by Mustafa’s confession that he’d been planning to rob the president’s residence, and that he’d intended it to be his final job in this country. If brought off successfully, he explained, it would have meant there were no challenges left for him here, and the time would have come to test his skills in other, more stimulating climes.

More surprisingly, however, his statements transcended mere confession to reach the level of theory:

The heavier the guard, the easier it is to get through. The higher the wall, the easier you feel on the other side of it, no matter how poor a climber you might be.

*

Why? If the question could be asked of any man and remain unanswered, it meant that he would be referred to us, for us to eradicate and remake it—innocent and free of question marks—as ‘Because.’ His coming to us was an admission that he was the best and most skillful in his field, a special breed of man who belonged with his ilk: unseemly geniuses, outcasts from the paradise of lawfulness.

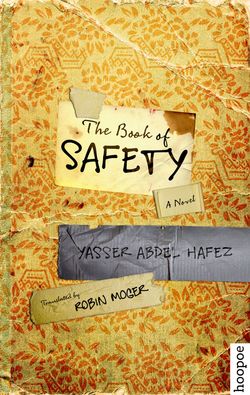

The purpose of our research was to uncover the aims of Mustafa’s organization and find any followers that he had not identified. There was concern that his ideas might spread and though his most senior assistants had been detained and had given detailed confessions, the suspicion that even one individual with the same mental powers might be lurking out there compelled our attention. Those who had been arrested were dangerous criminals. That was something we could accept. They were not particularly convinced by his views and credos, but had gone along with him in the pursuit of gain. It was quite possible, they said, that their criminal operations might have continued undiscovered, because the plans he laid adhered to a principle of absolute caution and were based on what he termed The Book of Safety, a volume containing hundreds of observations on the most propitious times to commit a crime, the risks that must be avoided, lists of addresses, the names of occupants and their professions, the phone numbers of state officials, escape routes and hideouts, instructions for issuing threats, and blackmail. It was a book he had fashioned with patience and love out of his experience and the experiences of others. He loathed error, seeking an ideal state in which he might attain absolute self-possession and control circumstances around him—a dream of perfection. En route to this state, he had managed to convert ordinary citizens into partners, some unwitting and others sympathetic to his ideas and dreams. What he hadn’t realized was that error occurs precisely when we are taking care to avoid it.

Even so, he would never have allowed his ideas to disappear, hence the fundamental question: to whom had they been passed on?

“We concluded you were trying to revive the legend of Robin Hood.”

“What do you mean by that? You’ve been unable to deal with us using the standard methods, so you’re taking refuge in myth? Or is this an honor reserved for me?”

For all his intelligence, Mustafa didn’t know what to make of the place in which he found himself. He attempted to conceal his nerves behind insouciance and grit, but there is no strength of will too tough for taming. The system grinds on, and has all the patience and all the time it needs to reach its goal—while Mustafa was a romantic who didn’t understand that it wasn’t the Sixties any more. He lived according to that era’s vision of the world, trying to assume the guise of a god. And the upshot? He had fallen into an elementary mortal trap. And like they say, you only need to fall the once to go on falling forever thereafter. I observed his bafflement in sneaked glances; skillful forays slipped into the flow of his words to keep his secret burnished. One day, al-Adl had gone out of his office, leaving us together. Dropping his impersonal air, Mustafa asked me directly, “Where are we?”

I was flustered by his boldness. We had never exchanged words before. I attempted an answer, filled with pride that he had noticed me, but most likely he knew that I was no less confused than he. For his part, Nabil al-Adl was intent on intensifying the mystery surrounding our location—his way of meeting Mustafa’s challenge to his authority:

“My job is not to condemn or exonerate. When it comes to our concerns, your guesses are wide of the mark. You cannot imagine the sheer number of unusual situations that we come up against and that oblige us to update our research techniques. Which is why, when I say that you are trying to revive the legend of Robin Hood, this isn’t some whim of mine, but a statement based on a report on you which has been specially prepared by an educated and experienced operative.”

I was the educated and experienced operative Nabil al-Adl referred to, and his kind words were not meant as a deft little summation of my person, but rather as the shot from the starting gun at which I must spring forward, must bite to inject the poison, the victim anesthetized so as not to cry out when he was skinned. Neither pain nor blood held any pleasure for us.

“We are the most refined and respectable level of sadism.”

This would be my answer to the meaningless definitions of our trade bestowed on me by Abdel-Qawi.

With childish malevolence, al-Adl was trying to embroil me in an enmity with Mustafa, but I ignored it. I didn’t enter into the conversation, hoping that Mustafa would be aware just what I was offering him. But he did not take the bait. Instead, he set about destroying my pet theory, giving al-Adl what he was after:

“I’m no reformer or political leader. I just rob rich people because they own what’s worth stealing, and maybe because they don’t miss what’s gone missing. I don’t mean whether or not they’re psychologically affected, of course. That’s not my point. It’s just that with a little pressure they manage to turn a blind eye to what’s been stolen—and they don’t report it, which is how I manage to avoid situations like the one I’m in right now.”

“But our investigations show you gave some of the money you stole to the poor. That proves you were attempting to turn yourself into a legend, to be whispered about by the people. . . .”

“Contrary to what you believe, I’ve no sympathy for the poor. In my view, they are largely responsible for their condition. There is something called the human will. If those who possess it don’t use it to escape their predicament, then they’ve no one else to blame. I worked harder than you would believe to plan and carry out each theft. Do you think I’d do all that for the sake of some pauper who just sits there whining day and night? Plus, I don’t consider what I’ve done as something wrong that I must atone for, nor am I so dead to the wellsprings of satisfaction that I have to get it from making others happy.”

The interview would come to an end, and his words would echo in my mind, so that it was no hardship to rewrite them when I returned home, adding to them my own interpretation of how the interrogation was proceeding, the questions that Nabil al-Adl should have asked or that he’d asked at the wrong time.

How did you come to take up thievery?

How did you come to justify it?

The truth is that it becomes easier when you define your options quickly. Abandon whatever resists you and take what comes to you. To turn failure into success—to transform from one thing to its polar opposite if need be—is a power you gain by looking hard at your disappointments. Where does it come from, this power of transformation? From university professor to thief. From lawful to illicit. This is our nature; if you are not aware of it, you will be lost—an astonishing mix of earth, and water, and fire. I am testing myself, nothing more. Later, perhaps, I shall become something quite different.

Can this be mine? Can I transform? I appreciated how difficult it would be, the transformation that Mustafa—who, for all his symbolic violence, was a traditionalist—had made from good to evil. A human story repeated a million times over, his own personal contribution a reversal of mankind’s general law: the evildoer who gropes his way toward good. He had his own private concepts, and there were no ethical concerns to hamper his transition from one code of conduct to the next.

I proceeded in a daze: no signpost to teach me good from evil. Over and over, I reread the thoughts of the philosophers and thinkers, yet the distinction remained elusive. And I came to believe that they, like me, had not been able to separate the two principles. Then I understood that to rise above this system one must first pass through it, one must experience good and evil for oneself, and that I’d been nothing but a fool to believe that observation and reading could be fit substitutes for getting involved. Such lies. Writers are liars. Fools like me. They stick to the shore and write down their fantasies—and those fantasies took me in. I thought them the product of experience, when they were just the product of impotence and fear.

In your victim’s home, do not act like a blundering thief driven by resentment to wreck and destroy.

Treat the site of your burglary as though it were your own home. Do not hurt the feelings of others by violating their privacies unless you must prevent them reporting what has happened.

Maintaining a respectful distance between yourself and those whose homes you invade ensures that you retain control over feelings that should not be allowed to guide you in those moments and thus spoil your work.

Mustafa Ismail

The Book of Safety