Читать книгу Witness to War and Peace - Ahmed Aboul Gheit - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

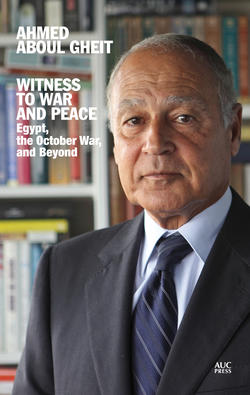

The idea for this book was born on October 6, 2009. On that day, I wrote an article for Egypt’s premier national newspaper, al-Ahram: it was a character study of the Egyptian national security advisor during the October War, and my personal experience of him over two years from August 1972 to February 1974. During that period, I witnessed firsthand the Egyptian national security apparatus’ preparations for the war, to reclaim Egypt’s honor and pride after our defeat in June 1967. Directly the article, titled “24 Sa‘a jasima fi hayati ma‘ Mohamed Hafiz Ismail” (24 Decisive Hours in My Life with Mohamed Hafiz Ismail), was published, I received a great many encouraging comments. Many people asked me to write more about this period, a watershed in Egypt’s military and political history, as, they said, we desperately need more genuine and serious documentary sources covering this critical and historic time in Egypt’s national efforts.

Gradually, I acceded to their requests. I wrote more pieces on the October War and my personal experiences with the office of the national security advisor. This continued from October 2009 to October 2010. The articles, twelve in total, together formed a series entitled, “Witness to War.” Their publication elicited surprise from readers. How, they asked, could a sitting foreign minister, with all the weighty responsibilities of this challenging and critical period in Egyptian history, find the time to write all these articles, including the minute details of the 1973 military conflict that he set down at the time?

It became clear that a great many people felt that these articles constituted a useful addition to histories of our armed conflict with Israel. In October 2010, while still foreign minister, I began to realize the importance of writing down my eyewitness accounts of the stages of Egyptian history that spanned the October War and its aftermath.

Two factors encouraged this endeavor and compelled me to write things down for posterity. The first was the declining health of Dr. Osama al-Baz, political advisor to the Egyptian president for more than thirty years. His memory was failing and the chance had been lost for him to document his long experience with the Palestinian struggle, the Palestinian–Israeli settlement, and the Arab–Israeli conflict. The second factor, of equal importance, was the sudden death of Minister Ahmed Maher al-Sayed in September 2010. His death was a shock to us all. His friends and acquaintances had similarly wanted him to write about his experiences with the Arab–Israeli issue, especially during his tenure with National Security Advisor Hafiz Ismail during the October War, and with Egyptian Foreign Minister Mohamed Ibrahim Kamel in the period from Sadat’s historic visit to Jerusalem in November 1977 to the Camp David Summit in September 1978 and Minister Kamel’s resignation. During this period, Ahmed Maher did a great deal and had profound influence. We had always thought that he would write his memoirs, submitting his vast wealth of experience for publication. But this did not occur, for reasons I never fully knew. It was a great loss not only for Egypt but also for our diplomatic history. For my part, I had tried over and over to urge and encourage Osama al-Baz and Ahmed Maher al-Sayed to “write, write, set it down!” The first was struck by an illness that destroyed his memory, while the second left it till too late. We shall all strut and fret our hour upon the stage, and then be heard no more. Therefore, I have decided to write while I still can, work and duties notwithstanding. I have written what I can. There may not be time in the future, so here are my testimonies of important, even critical, moments in the history of Egyptian diplomacy.

In the final months of 2010, I wrote eight more articles, entitled “Witness to Peace,” also published in al-Ahram. When I left my ministerial post on March 6, 2011, I decided to write about more of my experiences in the period starting with 1967 to my appointment as foreign minister on July 11, 2004, when I succeeded my dear friend and staunch supporter Ahmed Maher al-Sayed. This book covers and evaluates all the events I witnessed personally starting with June 5, 1967, through the October War and the extended peace process that started with President Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem, and throughout the years that followed.

The Palestinians have suffered a great tragedy. The Arab and Islamic peoples and governments have stood with them in a strong show of support, yet all the Palestinian and Arab efforts have ended in failure. Many have used the Palestinians, and many have exploited the Palestinian cause, to achieve their own narrow ends. Egypt has worked consistently toward achieving their liberation, despite all the difficulties and divisions among Arabs and Palestinians, the criticisms and squabbles. Some in the Arab world, and indeed in Egypt, felt that we needed to press on with the October War until the Palestinian goal was realized, namely reclaiming every inch of their homeland intact. They ignored the inequitable balance of power between the Arabs (including Palestinians) and Israel, and assumed that the western world and the United States would just leave Israel at the mercy of what they viewed as Arab and Islamic aggressors. They pretended that the Arabs were capable of coming together and mobilizing their forces against the west and Israel during that period of western advancement and Arab backwardness.

Egypt’s decisions from June 9, 1967, until today have been aimed at getting rid of the fallout from Israel’s act of aggression and the Arabs’ defeat, followed by building a suitable modality that allows the Palestinians to establish a Palestinian state on what remains of Mandatory Palestine, the principle being two states on Palestine’s land, one Israeli and the other Palestinian. Egypt has achieved some successes, and encountered some setbacks. It still embraces and assists this just cause, in the face of occasional absurdities and blackmail.

The reader will note that the first chapter of the book covers what I call the silent and secret war between Egypt and Israel. In it, I present my personal experiences, which I feel are important to set down, not only in memory of a member of Egyptian Intelligence who worked tirelessly for years against Israel, but also to underscore the great efforts of this Egyptian national apparatus from its inception in 1957 to the present.

Mention of my personal experience in this field, while extremely limited and not to be compared with that of actual Egyptian Intelligence agents, may help the reader understand the dimensions of the conflict. It was not only a military effort, nor a diplomatic challenge. Egyptian Intelligence has made remarkable efforts to supply Egypt with the information it needs to succeed in its confrontation with Israel.

I now return to the defeat of 1967, to say this: it was a profound and shattering blow to every Egyptian of that generation, and it sorely intimidated anyone in a position of responsibility or on the way to assuming one. I speak of those Egyptians born in Egypt between 1914 and the start of the Second World War, who lived through the Second World War—the generation, in other words, who were between twenty-two and fifty-three years of age in 1967, the most influential and productive age group in any nation. This crushing blow intimidated that generation, but it did not break them. They stood firm, and struck back. For a long period, they prepared their counterstrike. I know, for I was one of them.

In June 1967, I was twenty-five years old. I was already an aficionado of war, military life, and strategy. I had been living in the Royal Egyptian Air Force Base (renamed the Egyptian Air Force Base after the 1952 revolution and the union of Egypt and Syria) since before 1952, closely following the work of my father, the pilot Ali Ahmed Aboul Gheit, throughout my formative years. I followed the battles of 1948–49 with a great deal of confusion and incomprehension. My father was away every day, and came home very late at night. My mother was always worried. Every night, when he came in to kiss me goodnight, I would ask, “Where do you go every day? What do you do?” He would reply, “I was bombing the enemy.” When I went outside to play with the other pilots’ children, it was only natural that we played war and “air raid.” This was how I first learned about enemies and war.

I would listen with great attention to my father’s chats with his fellow pilots. I recall many of their names even today. I also began to learn the types of aircraft then in use in the Egyptian air force—fighters, bombers, and U.S.-made Dakota and Commando transports, tweaked by Egyptian technicians for use in bombing enemy airfields and installations. We called them “the colonies” in those days. Later, over the decades, they came to be called “the settlements.” I also learned the names of our military airfields—Almaza, Cairo West, Anshas, and Bilbeis—upon which the Egyptian air force depended.

The 1948–49 wars were a tragedy for the Egyptian army. They were sent into battle unprepared, without any conception of the abilities of the Zionist gangs supported not only by the west but also by the Soviet Union, along with the rest of the Eastern European countries that were completely subservient to the Soviets’ will. No one in Egypt after 1949 realized that Israel was on the verge of seizing the cities of Rafah and Arish toward the end of the conflict. We should have known about Israel’s burgeoning capacities.

I have read extensively about this war. I have also attempted to study the conflict in Sinai when the Turkish-Ottoman army conducted a raid on the Suez Canal and attempted to invade it in 1915, as well as Lord Allenby’s campaign in which he invaded Palestine and Syria in 1917. The Egyptian army’s movements in the 1948 campaign lacked a strategic vision and ignored the lessons of then-recent history, namely the First World War, or indeed of ancient history, namely the Egyptian army’s battles in the Mamluk era and all the way back to Ancient Egypt. Egypt’s military leaders were blind to the pivotal importance of the city of Bi’r al-Sab‘, currently Beersheba, which was in fact the key to the entire Egyptian campaign. Egypt paid the price not only for a feeble strategy, but also for many other reasons known to experts, about which much has been written and which are outside the scope of this book.

For all that, I would like to relate a brief anecdote that reflects just how little we knew about the details of this war. In 1958, I heard my father tell a story about the pilots at Almaza Airfield just a few days before the Zionist state was declared on May 14, 1948. Some of them proposed an air raid the moment Israel’s statehood was announced, to bomb the Jewish Agency in Tel Aviv and destroy the Israeli project in one fell swoop, not to mention Ben Gurion and his men. Some of these pilots, enthusiastic young Egyptians, took to searching for a detailed map of the city in hopes of pinpointing the Agency headquarters to facilitate the attack—immature to say the least, not to mention unrealistic.

The next attempt to engage with Israel militarily came in 1956, when I was fourteen. Both Egypt and Israel had by then expanded their military capacity considerably. There were now MiG-15s and 17s in the Egyptian arsenal, replacing the UK-made Second World War Hurricanes and Spitfires and American P-51s. The British Vampires and Gloster Meteors, though, had not been retired from active duty. The Ilyushin Il-28 and English Electric Canberra bomber aircraft had replaced the 1940s-generation Lancaster and Halifax Sterling aircraft that my father flew. We also had a very limited number of Flying Fortress B-17s. This was the entire arsenal of the new Egyptian air force in 1956. On the Israeli side, there was an array of Dassault aircraft: the French-made Ouragan, the Dassault Mystère, and the Dassault Super Mystère. France had begun supplying weapons to Israel to repay Egypt for Cairo’s support of the revolution in Algiers.

Israel was a close observer of the Soviet arms deal with Egypt in 1955–56, and Egypt’s rapprochement with the Soviet bloc to obtain weapons. What is certain is that Israel, and the western powers behind it, decided to stand against Egypt and abort this burgeoning relationship between Cairo and the capitals of the Eastern bloc, in addition to those of the Warsaw Pact. When Egypt regained the Suez Canal via nationalization in 1956, Israel seized its chance. The battle of 1956 was an excellent opportunity for the United States to inherit the spoils left by the aging empires of Britain and France.

My father was at the time second in command of the Egyptian Eastern Air Command in the Suez Canal. His living quarters were the Galaa camp in Ismailiya, from where he traveled regularly to our home near the Heliopolis Airport, and where we spent long months between furloughs. With the start of Israel’s aggression against Egypt, fully coordinated with France and Britain, on October 28, 1956—I see no need to go into details which others have covered and the reader knows well—I saw my father telling his comrades in the air force, who had attended extensive training sessions at the Royal Air Force College in Andover (where I accompanied him in 1955–56), “It is extremely important to prepare for what Britain may do immediately after the implementation of the joint British–French warning to cease warfare between Egypt and Israel, and for both parties to move ten kilometers away from the canal to the east and west of the waterway. This will place the canal under the de facto control of the two colonial powers, England and France.”

The Egyptian Air Force Command, as I understood later from my father, was working independently of the rest of the army in Sinai. We tried to avoid this lack of coordination when the Israelis next struck in 1967. In any case, Egypt’s efforts at the time were concentrated on protecting the air force from the strikes it would inevitably sustain with the start of Britain’s military action against Egypt. My father, just a few months back from a year of study in Britain, had an understanding of how the British would conduct aerial operations in such conflicts. The Royal Air Force would first focus on enemy airfields, air bases, and installations by conducting night raids and high-altitude bombardments aimed at crippling the opponent’s abilities and closing their airfields, concentrating on the runways. At dawn, it would commence with attacks on aircraft on the ground, which would be unable to take off because of the lack of runways. Another option would be to lay bombs, or timed explosives, along the runways, threatening anyone who used them.

A great many Egyptian air force commanders studied in Great Britain in the years that followed the 1952 revolution; they therefore knew what was coming. They had no night-flying fighters to defend their forces and installations. Their efforts over the days that followed, therefore, concentrated on concealing our aircraft, to protect them from being bombed on the ground. Highways were used as runways. Unfortunately, Egypt’s highways at the time were few and ill-equipped. These places were called “secret airfields” at the time, although there was nothing secret about them! Everyone knew about them, where they were located, and what they were for.

The Egyptian air force commanders’ predictions came true. Our bases and installations were attacked. It was a terrible night. I recall the heavy bombardment on the night and evening of October 30: violent tremors rattled through our home, at the officers’ housing near Heliopolis Airport, and the Egyptian air force headquarters. We eventually had to leave, and spent a few days at my aunt’s house. My mother’s sister lived not far away, in Ismailiya Square in Heliopolis.

Sure enough, the French—or Israeli, I should say—Mystères and Super Mystères attacked our airfields at dawn, after the British bombers had incapacitated them the night before, in an attempt to destroy our fighters and other aircraft on the ground. Credit where credit is due: I saw Egyptian fighters chasing off the attackers on October 31, and pitched air battles raging over the Cairo suburb of Heliopolis.

Egypt’s pilots, while outnumbered, proved their courage and tenacity in defending the skies of the capital city, and elsewhere. Effort and ability can only go so far, however, in fighting the resources of an empire.

My father came home to Cairo on November 2. The air force headquarters at the Suez Canal had been vacated, and all airfields there were out of action. He immediately set out to rehabilitate what fighters and bombers we had available, and rebuild what air bases remained deep within Egypt. The battle caused heavy losses for Egypt’s army and air force. The city of Port Said was occupied. However, the intervention of the United States and the Soviet Union to stop operations against Egypt, coupled with the fact that Egypt was clearly prepared to keep resisting and fighting, aborted the plot. Egypt won strategically and politically, despite its heavy losses on the military front.

The military errors in battle did not go unnoticed, nor did the insufficiencies in Egypt’s performance in all its military fields. However, the fighting spirit of the combat units, the pilots, and others may have led to the lessons of the battle being forgotten—in other words, there was no frank and objective discussion of the mistakes that were made. The times did not allow for it.

Ten years were permitted to pass, from 1957 to 1967. We spoke exclusively of the success of the battle at the Suez Canal, while all shortcomings were swept under the carpet. We paid heavily for this in June 1967.

At the time, I hungrily devoured every scrap I could read on the battles of 1956. Between 1957 and June 1965—the year I joined the diplomatic corps—I pored over books on warfare and strategy. I make no boast when I say that I read dozens of books in that period, by the greatest writers on strategy, warfare, and international relations. The year I spent at the Military Technical College in 1959 only whetted my appetite for reading on this subject. It is my conviction that this had a decisive effect on the formation of my character, worldview, and values.

My increasing reading, for longer and longer hours every day—even during the academic year—were making me increasingly doubtful of our military capacity, especially with Egypt’s military venture at the time, in Yemen. This had a negative impact on the abilities of the Egyptian army, from October 1962 up to our defeat in June 1967. I often discussed these subjects with my father, who retired from active military duty in 1962, with the enthusiasm of youth coupled with information from my reading, especially on the Second World War on all its fronts. I was gradually moving toward a more profound and wide-ranging understanding of what lay behind these battles, their technical details, the types and capacities of their weaponry, their military tactics and commanders—their command styles, how qualified they were, and how they had earned their stripes. I thought out loud and discussed all this with my classmates, the young officers who graduated from military colleges between 1962 and 1965.

At this stage, I was preoccupied with, not to say apprehensive about, our military capacity, a matter I discussed with many of my friends who had an interest in our war with Israel. These were years of continual talk of combat, of challenges, of (on Israel’s part) diverting the course of the River Jordan, of Arab unity and shared Arab army action. Our group included Mohamed Assem Ibrahim. The son of an army general, he joined Egyptian Intelligence after his graduation in 1966. He spent nine years there before passing the qualifying exams and moving on to the Foreign Ministry. His illustrious career in the ministry includes posts as Egyptian ambassador to Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, and Israel from 1995 to 2008. As a young man, I spoke with a great many junior officers, including Ali Abd al-Moneim Mursi, Sherif al-Hakim of the Artillery Corps, Hamdi Khattab from Air Defense, and many others, all my colleagues either at school or at military college. I also discussed the war with some other friends in the air force, such as Ahmed Sadek al-Gawahirgi, Kamel al-Mawawi, and many others.

My overriding preoccupation was that Israel might attempt to destroy the Egyptian air force with a surprise strike on a Friday morning, which is a general holiday for our bases and airfields. What reinforced this feeling was that I had often observed large numbers of pilots and military men on Fridays congregating at the sporting and social clubs in Cairo, leaving only skeleton crews at the bases. We discussed this discreetly, allowing our imagination full rein on how and when the Israelis would strike. We read often of Nazi Germany’s Barbarossa strike against the Soviet Union, and how the Luftwaffe successfully destroyed the Soviet air force with a surprise preemptive strike at dawn on June 22, 1941. Thousands of Soviet aircraft were destroyed on landing strips and runways, with no resistance. I recall that some of our air force commanders resisted strongly when Egypt began to discuss and implement the new Soviet combat organization, and Soviet combat approach, starting in 1959–60. They kept saying that the Soviet Union was hardly a role model insofar as air forces went!

I spoke to my father about this. He was an expert on the use of aerial force: he had served in the air force directly on graduation from the Royal Egyptian Air School in April 1939 and remained there until 1962, and had been on many training courses in the United Kingdom. He discussed it with me, but told me to concentrate on my studies and career. “Don’t think so much of war!” he told me. “It won’t go that far.”

It was the summer of 1964. The African summit was held in Cairo in July of that year. Israel attempted to embarrass Egypt by breaching Egyptian airspace in Sinai with several Mirage aircraft. They were confronted by Egyptian fighter aircraft, but the latter were slow and ineffectual. To a young man like me, already carrying a deep-rooted fear, this event sounded a definite and loud alarm.

On a Saturday morning in August 1964, I was at Nuzha Airport in Alexandria, getting ready to return to Cairo after two days in the famous resort city. Suddenly, I saw Lieutenant-General Mohamed Sidqi Mahmoud coming in, getting ready to board the same plane as me. I knew him very well, as my father was director of the Air Navigation School at Dekheila Coastal Airfield, west of Alexandria, when Sidqi Mahmoud was commander of the Airfield Station from 1950 to 1952. We were also neighbors in the officers’ quarters at Air Force Command from 1952 to 1957. I sat next to him on the plane and spoke to him with quite extraordinary boldness about what preoccupied me, namely my fear of a sudden Israeli airstrike on Egypt.

To his credit, Sidqi Mahmoud listened attentively to my thoughts, though I was only twenty-two at the time. Finally, he said briefly, “It’s impossible. Israel can’t carry out a surprise attack of that kind.” He went on to say that many of our bases and main airfields were out of Israeli air striking range.

For years, I buried myself in my diplomatic work. The Israelis struck on June 5, 1967. I buried myself again in books about war and strategy, and anything and everything related to armed confrontation between nations. It was still June 1967 when my father came to me and said, “We should have let you join the army, Ahmed.” But I was not destined to serve in the army.

Much has been written—thousands of pages and millions of words—on the different aspects of that war, and the negative Arab and Egyptian aspects it revealed. But the truth of the matter is that many of the faults and errors were already known to a number of the junior to middling commanders in the Egyptian army and air force. Egypt’s presence in Yemen from 1962 to 1968 had a severe negative impact, although it is not within the scope of this book to expand on this. Also, the management of the armed forces, and the system used for promoting officers and army commanders, was fundamentally flawed. One of these flaws was the routine dismissal of commanders and granting of civilian posts, justifying this as “improving the civilian structure of the state by nourishing it [sic] with military men,” without the slightest understanding of the effects it would have on the efficiency of military leadership, to say nothing of the civilian branch. One day, in the spring of 1966, I spoke about this with a very close friend of my father’s, Staff Major-General Abd al-Moneim Riyad, who is now a household name. I still recall his evident terror at what might befall me if I ever made these opinions public. “Never, ever say that kind of thing again!” he said firmly. “Not to me, and not to anyone else.” I got the message.

Back to August 1964, and my meeting with Mohamed Sidqi Mahmoud on the flight from Alexandria. I suggested he prepare for surprise maneuvers one Friday morning, to test the efficiency of the air force at that time: a surprise full air drill. The man listened again, intently, then replied curtly, “Impracticable. Impossible. The political and security status of the nation won’t allow it.” His response reveals a great deal of what was wrong with the Egypt of the time, along with its armed forces. The attack of 1967 plunged it into the worst possible strategic circumstances any army could face.

Now to the second half of this book, which in truth could be a book unto itself. It covers Egypt’s efforts to effect peace with a view to ending the Arab–Israeli conflict and finding a solution to the Palestinian problem, so as to allow the Palestinian people to reclaim rights to their land. This half covers all that occurred as I saw it or took part in it, starting with President Sadat’s historic visit to Jerusalem in November 1977, up to my appointment to the post of foreign minister of Egypt in 2004. My part in the peace efforts throughout my years as the head of the Egyptian diplomatic corps from 2004 to 2011 is documented in my book on Egyptian foreign policy, Shahdati: al-siyasa al-kharijiya al-misriya 2004–2011 (My Testimony: Egyptian Foreign Policy, 2004–2011), published in Arabic in January 2013. It may be useful to consider it a companion volume to this one.

As I was saying, the second part of the book starts with Chapter Fourteen, with the events of the Mena House Conference, held as a direct result of Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem and the Ismailiya Summit that followed, after which Israel presented its plan in an integrated proposal for an Arab–Israeli settlement, covering Palestine and the occupied territories in Sinai. This half of the book covers the efforts of the Political Committee and the Military Committee, both Egyptian and Israeli, formed at the start of operations at the Ismailiya Summit. It goes on to describe the obstacles Israel placed in the path of the negotiations and Egyptian negotiators’ rejection of the Israeli propositions. The situation became more involved; Egypt redoubled its efforts to win over the United States to its way of thinking and to pressure Israel to soften its position. This effort continued for months, from January 1978 until the Camp David Summit in September of that year.

At this point in the book, there is an evaluation of the way the United States succeeded in securing the agreement of the two sides, convincing them that each had achieved its main goals in going to Camp David, even though both sides had, of course, been obliged to make some (possibly vital or essential) compromises. The United States used every carrot and stick in its arsenal to make this deal a reality.

After this, I demonstrate Egypt’s attempts, after the signing of the peace treaty in Washington, to link the Egyptian and Palestinian peace processes, accompanied by Israel’s maneuvers to completely separate the two. The following chapters offer an overview of the preparations for the Madrid Summit, and the Oslo Summit after it. Finally, I show the role of the United Nations in convincing the countries of the world of the need for a Palestinian state side by side with the state of Israel, via the important Resolutions 1397 and 1515—the first-ever Security Council resolutions in the history of the Palestinian conflict to directly address the establishment of the state of Palestine.