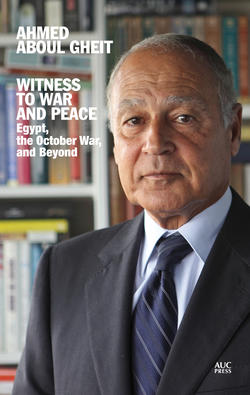

Читать книгу Witness to War and Peace - Ahmed Aboul Gheit - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5 The Battle Approaches

In this chapter, I reexamine what I have called the time leading up to battle, and the crises of the first week of war. Two main points must be stressed, and anyone following the conflict closely, who lived through those days, will recognize the importance of mentioning them before launching into an overview of that historic conflict.

First, I am writing today of events that occurred forty years ago. During those days, I recorded a great deal about the events in diaries, documenting my observations. I commented on what I observed moment by moment. Today, so many long years later, I have gone back to reevaluate what I wrote in the heat of the moment, reaching conclusions about my observations at the time and their continuing effect on Egypt, its view of war, and its exigencies today. Of these diaries, I need to emphasize that I was writing about my personal experiences, not relying on the writings of others who might have taken part in some way or another in the events. I am not writing in order to respond to anyone’s evaluation or to any issues. Finally, it is not my intent to review or evaluate the writings of Arab or foreign military analysts or historians who have attempted their own analyses of this conflict as a whole or even its minute details—quite the contrary. It may appear sometimes that I disagree with them, but what is certain is that what I write now has its source in meticulous records made at the time the events were actually taking place, as I lived, read, or experienced them.

These diaries were made from October 5, 1973, at 2130 hours, to 1700 hours on November 25, 1973. That is when the diaries stop. I attempted, when writing them, to set down with great brevity what was happening for the duration of those fifty days—a great deal. I regret this somewhat today; history was being made before my eyes, and perhaps I should have recorded a great deal more than I in fact wrote down. However, my method was influenced by the great number of diaries I had read by important military and political figures of the past, especially from the Second World War—figures like Franz Halder, chief of the Oberkommando des Heeres staff, and Field Marshall Alanbrooke, chief of the Imperial General Staff during that war, among other famous and influential individuals. Their diaries are short in length, precise in nature, and avidly read by great strategic commentators. For a great many students of military strategy, they still light the way toward understanding the philosophy of the clash of powers in war as a means to achieve countries’ and societies’ objectives, and the combination of diplomacy and war when great powers and peoples engage in conflict.

Some may imagine that I seek to compare myself to these great figures of history, that numerous company of outstanding military and diplomatic leaders who have left us their enlightening observations. But the truth is that my goal in 1973, as it is today, consisted in showing my countrymen what I saw at the time, aside from any duties I may have undertaken or positions I may have held—up to foreign minister of Egypt, the greatest Arab country and one of the most influential powers in the affairs and development of the Arab region.

The second point I would like to emphasize also has to do with the mission I undertook at the end of my journey in the service of Egyptian society, namely the responsibilities of foreign minister of Egypt. In that role, my task was to plan Egyptian diplomatic affairs and implement a successful and influential foreign policy to protect and secure Egypt’s national and strategic interests, in a region plagued by tensions morning and evening as a result of this event or that.

The obligations of my past public service bind me even today: I shall always scrupulously avoid speaking of subjects that might negatively affect our relations with other parties. On the other hand, I am no less scrupulous in reporting my observations and thoughts utterly honestly; I recorded these with the reverence due the written word, and great care for accuracy and clarity. All of us who worked with Hafiz Ismail could sense that something great and momentous was underway. This feeling intensified in light of a great many indications, of which I took precise, written note.

The most important of these indications of approaching war was what I noticed on a day in August 1973: the name of then Brigadier General Taha al-Magdoub, chief of the planning branch of the Armed Forces Operation Department, on the national security advisor’s meeting agenda. That day, I saw that scowling, swarthy military man, with typical Egyptian features, walking down the long corridor in Abdin Palace to Hafiz Ismail’s office. Along that corridor were situated the national security advisor’s office and that of the presidential secretary for information, a post then occupied by Dr. Ashraf Marwan. I noticed at the time—or think I noticed—that he was wearing dark khaki battle dress and a green beret.

This visit was repeated—to my surprise—two more times. None of us at Hafiz Ismail’s office, except for Ambassador Abdel Hadi Makhlouf, office director to the national security advisor, knew the reason behind these visits between Taha al-Magdoub and Hafiz Ismail. However, I must admit that when I was given the chance to open the iron safe I mentioned before and examine the documents and records pertaining to the war, I found out that Taha al-Magdoub had been sent by Ahmed Ismail Ali, commander in chief of the armed forces and minister of war at the time, to keep Hafiz Ismail abreast of the general framework of war plans, its strategic and mobilization goals, and its desired time frame. In my estimation, the cooperation between these two men—these two military giants, if I may say—was always optimal: they exchanged a great many ideas and proposals, sharing their information and views openly while displaying no sensitivities or competitiveness. Their main concern was the army: how best to build its capacities and abilities, and supply it with all the available resources to strengthen it for an upcoming battle that would restore Egypt’s dignity and recover Sinai, a main objective on the path to a possible settlement to the Palestinian issue.

Both Hafiz Ismail and Ahmed Ismail Ali were old-school Egyptian military men. As young men, they witnessed the Second World War being waged in the Egyptian desert. Doubtless this left its mark on them, both in terms of understanding military strategy and the use of armed forces within a general strategic framework, and the tactical details of how to use forces and weapons in all-out war, especially in the desert. This was the necessary introduction, and basic training, that polished their abilities for a confrontation with Israel in the Naqab (Negev) desert and in Sinai. Both were deserts where it was necessary to learn from the lessons of those who had trodden this path before.

These two men had also studied all modern military operations in North Africa, whether of the British Eighth Army under Montgomery and his predecessors, or the Germans’ North Africa Corps under “the Desert Fox,” Erwin Rommel. Hence, they both understood the effects of each specific weapon on the outcome of a battle. They equally grasped the role of the tank as the master of desert warfare, but also the effectiveness of antitank RPGs in open desert country. They understood, to expand upon this, the effect of infantry soldiers stubbornly standing their ground. They were well aware of the dreadful power of aircraft to cause ground troops heavy losses during open movement, and hence the importance of concealment and camouflage, and similar arts. These two great men had been awarded the highest academic degrees in the 1950s, from the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst in Camberley, Surrey, and the Frunze Military Academy in the Soviet Union. They shared a great mutual respect, and a keen understanding of both the capabilities and the limitations of a given military force.

After the war—I have mentioned the circumstances of how this came about—I was granted access to the general framework of their plans, Granite 1 and Granite 2, which Taha al-Magdoub had, at Ahmed Ismail Ali’s request, entrusted to Hafiz Ismail for discussion with the commander in chief. I find myself pausing for a moment here to say that I thought it very odd for Hafiz Ismail to have mentioned the subject of that conversation at the Egyptian National Security Council Assembly on September 30, headed by President Sadat, and his differences with the commander in chief, especially as the documents in his office revealed the general framework of the war and the strategy for its military management. From some people close to Field Marshall Ahmed Ismail, I learned that he, too, was rather surprised by the position and vision that Hafiz Ismail presented to him on that day. However, what is certain is that this event did not affect their relationship, which remained strong to the end.

It remains to say that Brigadier General Taha al-Magdoub’s visits were not the only indication of war. Also telling was the sudden frequency of foreign diplomats contacting Egyptian ambassadors in different capital cities, all warning against the dire consequences of any military action. These included Russian statesmen who remained unconvinced of Egypt’s military ability and capacity, in a wide-scale battle with Israel, spanning the entire Suez Canal front, the Mediterranean, and the Red Sea. Naturally, as an Egyptian, I am inclined to believe in my country’s capabilities and its military capacities. Regardless, I believe that the root of our profound difference of opinion with the Soviets was their failure to understand the magnitude and profundity of the national humiliation we had suffered in 1967, and our desire to reclaim the honor of our military and our country.

In this the Soviets appeared not to have recalled their own lessons of the Second World War, when the Red Army emerged victorious. When defense of the nation and its honor motivates soldiers to commit their lives, armies—from the lowliest private to the commander of the main formation, or the entire army—can rise to the most severe challenges and pressures. With such motivation, responsible use of their capacities, proper insight, and adequate training and armaments, they rush aggressively to accomplish their mission, however impossible it may appear to others who fail to understand the power of the soldier’s will.

Indications continued during the summer months of 1973 that war was fast approaching. Israeli air reconnaissance attempts were intensifying, both on the front and deep within Egypt. Many intelligence reports sent to the president’s information secretary, with standing orders that the national security advisor always receive a copy, reflected an Israeli desire to find out intensively and minute by minute the movements of Egyptian forces, especially the air force, and to gauge their reactions to the Israeli sorties.

During this period, various world leaders sought to convince Egypt to seek peaceful, diplomatic solutions. Among them were Romania’s Ceauşescu and Yugoslavia’s Tito, who were widely seen as influential within Egypt and whose support for such diplomatic initiatives thus was presumed needed.

Amid these maneuvers, communications, and movements, Egypt was engaged in preparing the groundwork to reduce Israel’s, and thence the US’, capacity for diplomatic evasion at the Security Council, in an attempt to strip them of a great deal of their international support—support that would be urgently needed by Egypt if it did enter into armed conflict. Hence, Egypt presented the issue once again to the Security Council. However, to safeguard the secrecy of the Egyptian movements and objectives, and the reason behind Egypt’s call for a Security Council session, Hafiz Ismail sent me on a one-night mission in July to meet with our foreign minister, Dr. Zayyat, who was then in Paris. I was to bring him written instructions on the framework of our goals, in light of sensitive information that reached Egypt after Zayyat had already left Cairo for Paris and London for consultations with his French and British counterparts, hoping to isolate the Israelis and Americans.

August 1973 arrived in a buzz of planning and organization. Diplomatic preparations were at their height. In the second half of August, I accompanied Hafiz Ismail and the office director for the national security advisor Dr. Abdel Hadi Makhlouf to Romania and Yugoslavia. We met President Ceauşescu at a resort in Mangalia, on the Black Sea. Hafiz Ismail explained Sadat’s vision to Ceauşescu, mentioning his readiness to start indirect negotiations or proximity talks via Romania. He asked for Ceauşescu’s assessment of whether Golda Meir, prime minister of Israel at the time, had enough power and negotiating clout to accept a withdrawal from Egyptian lands and move toward an equitable settlement for Palestine, or if she still clung to her insistence that there was no such thing as a Palestinian people—to the extent that she once referred to herself as “We, the Palestinians,” denying the existence of that suffering people. We went on to convey the same messages to President Tito, in an even lovelier resort, the breathtaking Croatian city of Dubrovnik. Both leaders promised to convey Egypt’s views to Israel, whose eventual responses were chilly and arrogantly phrased.

Egypt set out on the course of war through the sweltering heat of August. The Egyptian public spent a preoccupied summer, full of speculation. I could see that hard times were ahead, and that I needed several days to recharge my mind and body. I needed to spend some time with my wife and son. Having obtained permission from Dr. Makhlouf for a short vacation, I took a trip to Alexandria.

In Alexandria, as was my habit every summer, I visited a close relative of mine, Vice Admiral Fouad Zikri, at his home in the beach suburb of Agami. As a thirty-year-old diplomat, I had an especially privileged relationship with a man who had twice been admiral of the Egyptian navy, once from 1967 to 1969 and again from 1972 to 1974. Zikri appreciated my interest in—my passion for—studying military history, war strategy, and the lives of historical figures, especially military leaders. He was something of a naval historian himself: his time spent studying in Britain and fluency in English had greatly broadened his knowledge. He was widely and deeply read in naval battle strategies, especially during the First and Second World Wars.

Our discussions were rich and varied. He was a serious and precise interlocutor. I told him of the indications I had noted, and that I felt it signified something momentous approaching, especially since the start of September 1973 tensions between Syria and Israel were escalating. Fouad Zikri’s comments were extremely guarded: “We will cut off their communications and block their naval routes. We will strike a forceful blow. We will confound their plans and teach them a lesson.” Since I knew him well, I assumed he was merely expressing his patriotism and his love for his country. I only understood what he meant after the war started, when Egyptian naval units revealed their presence at the entrance of Bab al-Mandeb and at the shores of Yemen—a message to Israel that controlling the Sharm al-Sheikh Straits, or Tiran and Sanafir, would do them no good, as we could close the Red Sea to Israeli maritime traffic, cutting off access to the port of Eilat.

I profoundly admired this man, who excelled at his command of the Egyptian navy in extremely difficult circumstances. He conducted its battles adroitly, showing great acumen and caution, achieving remarkable results that affected the outcome of the battle, especially toward the end. Over the years, I visited him many times, sharing a viewpoint or some detail that I had read in an article or book on naval battles. He was always a fount of expertise, not only as a navy man but also in his capacity as an expert historian with profound knowledge of virtually every aspect of naval history.

As we were talking at his home on the coast, the radio blared. It was an announcement of an aerial battle that day between Syria and Israel. Israel announced that it had brought down thirteen Syrian MiG aircraft. Zikri froze in shock and worry. We had only just been talking about a number of meetings between Egypt and Syria that had taken place in Alexandria, at the highest level, bringing together the commander in chief and the Egyptian commanders of the armed forces with their Syrian counterparts—meetings I knew of and knew that Fouad Zikri had taken part in. Zikri leapt up and launched into a flurry of telephone calls to the naval operations room, then to the armed forces operations room. He returned grim-faced: the Israeli announcement was in all probability accurate.

Only later did I find out that it was not only Fouad Zikri who was deeply troubled; all the leaders of the armed forces shared his emotion. They were, after all, preparing for the October military action and counting on Syria’s participation to disperse the enemy’s efforts and fragment Israel’s abilities with strikes from the north and south. I recall a conversation with then-President Hosni Mubarak about his experiences in the battles of 1973, during which I mentioned my experiences with Fouad Zikri—whom the former president admired a great deal—and that conversation in September 1973, after the news that a number of Syrian fighter planes had been downed. Mubarak told me that he, too, had been stunned by these losses and consumed with worry over the abilities, or lack thereof, of our ally, which would be fighting alongside us within a few short weeks.

The reader may recall that the first of the previous two chapters dealt with the start of the war and offered a record of the approach of battle and the first twenty-four to thirty-six hours. The second chapter dealt with the cessation of hostilities and the achievement of the objectives of war as set out by President Sadat and carried out by a sagacious and fully knowledgeable command of the armed forces, by an army well-trained, for over six years, to perform its tasks and what these tasks required. This chapter aims to cover the remaining days of that first week of war, including the crisis, or crises, that occurred, and always do occur during battles and armed conflicts, which served to reveal their leaders’ depth and determination, or lack thereof, with the accompanying results of victory or defeat.

One such example was immediately forthcoming, on Monday, October 8, according to my diary. On that day, Egyptian troops were still flowing into Sinai, the bridgeheads reaching as deep in as fifteen kilometers behind enemy lines. These five divisions succeeded in consolidating their positions into two bridgeheads: the Third Army in the south and the Second Army in the north. On that day, military intelligence reported that the efforts of the enemy’s air force were dispersed on our front, and that its ability to jam electronic signals was limited. It became clear that Egypt had destroyed the Bar-Lev line, in which the enemy had placed a great deal of faith. The army waited for the Israeli counterstrike, which never came. Our forces repulsed the Israelis’ several disperses counterstrikes, dealing them heavy losses.

Meanwhile, there were indications that Syria was also achieving great successes in the Golan; their armored units had almost reached Upper Galilee. However, the Israeli air force was concentrating on repulsing the direct Syrian threat to Israel, and Syria ultimately sustained extremely heavy losses. Soviet sources began to speak of a Syrian desire for a cessation of hostilities, content with its successes so far. In my diary dated Monday, October 8, at 2330 hours: “Syria is leaning toward a ceasefire. The Soviets are repeating this in several capital cities.” I felt intense worry—fear, even—about the repercussions of this situation if it should prove true. Israel might accept the ceasefire, leaving their army free to concentrate on the Egyptian front. My diaries for October 8 end at 2400 hours, with:

The Soviet military command is notifying us, based on their close observation of the progress of fighting, that it is concerned that our bridgeheads lack sufficient depth of penetration. President Sadat is reassuring them that we will persist in deepening these bridges, and bring them together into two main ones.

Tuesday, October 9, came. At 0200 hours, my diary reads:

Enemy attacks are still isolated and unable to breach our bridges. Enemy air force activity has failed to achieve its intent, namely blocking the consolidation and preservation of supplies and equipment and ammunition to the two armies in Sinai.

Syria reappears in the diaries:

Our information from the Soviets, and our other official sources, reflects that Israel has forced the Syrian army to withdraw once again from the Golan, with debilitating losses. The Syrian forces fought with incomparable courage, especially the armored units, which sustained great losses.

In addition, Israeli armored and aerial forces have launched intense activity focusing on the Egyptian front, in attempts to breach the bridgeheads, especially in the central sector of the Second Army, or to breach the missile battery defenses on the west bank of the Suez Canal.

The 0200 entry on October 9 reflects the difficulty of the situation and the approaching crisis. Minister Abd al-Fattah Abdullah, minister of state for cabinet affairs was with President Sadat at Tahra Palace and had attended and taken part in every meeting held by the president with ambassadors and other statesmen. He returned to Abd al-Moneim Palace, also known as Hurriya Palace, to transcribe the recordings of the meetings that had taken place that day. Dr. Abdel Hadi Makhlouf tasked me once again with supervising—and assisting—the typist on duty. All the contents of these documents were extremely classified, not to mention the additional effort required to decipher the arcane and baffling handwriting of Abd al-Fattah Abdullah!

The contents of the minutes shocked and disturbed me. Leonid Brezhnev, the general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and the main Soviet decision-maker via the Politburo of the Communist Party, said that Syria wanted an immediate ceasefire. Brezhnev not only encouraged this, but also urged President Sadat to accept it, for fear that the military march might continue into Damascus. Not only would this, needless to say, pose a catastrophic threat to the region, it would also seriously damage Soviet interests in the region and its relationship to the other superpower. I must admit that I was terrified at the danger posed by this Soviet message. However, Sadat’s response was decisive: Egypt would persist with armed confrontation until Egypt’s political objectives were achieved in their entirety.

“This is a historic occasion with Syria,” I wrote in the same paragraphs penned in the small hours of October 9. I went on to say:

The president is sending an envoy to the Syrian president to impress upon him the importance of pushing on with the battle, switching now to defensive mode, with the objective of attrition; more military must be requested of the Soviet Union as part of the military supply, and the slow-moving Iraqi army must be brought into the war effort.

Now, in my overview of Tuesday, October 9—the daylight hours of that day—comes the time to record the events of 1830 hours.

The situation is good. Extremely heavy enemy losses. All counterattacks repulsed. Enemy is exhausting its forces in parts, not as a comprehensive whole. Their losses are a direct result of their hasty efforts to make a dent in our forces. The 190th Israeli Armored Division is a good example. Ahmed Ismail telephoned Hafiz Ismail at 1600 hours to tell him that the Israeli armored divisions facing our forces are no longer able to fight. Hafiz Ismail says the army will advance when the stage of reorganizing and rearranging for the famous and much-talked-about regrouping effort is completed.

—an effort which I shall discuss in more detail later.

I must not forget to mention another event which took place that day—a day when all the news from the Egyptian front was positive. I had a chance to converse with Hafiz Ismail on the balcony of the palace that evening. Now he felt he could meet with any Israeli official on the spot—Yigal Allon, to be specific. The man with the different ideas for reaching a settlement with the Arabs. He was prepared to meet him anywhere, now that the army had struck and revealed the limitations of their capacities.

I was astonished at the boldness of his thinking, and this initiative. The truth was, however, that his attitude reflected how deeply he appreciated the results of military action, and his intention of using these successes to achieve the required political advantage and aims. My diary at 2000 hours on Wednesday, October 10, says:

The Soviets are pressuring the president to agree to a ceasefire. The president categorically refuses. He raised his voice with the Soviet ambassador and threatened to expose the Soviet position. He also demanded that the Soviets keep up the flow of equipment, bridges, and aerials needed for the missile batteries, as well as an urgent air bridge—or else he would tell the entire Arab nation the truth. Clearly the Soviets are under pressure from the US, which is doubtless what President Sadat fears as well.

The decisive paragraph that day—indeed of the first week of war—deals with Sadat’s telephone call to President Hafez al-Assad. The Syrian president indicated his conviction that Syria’s military position was very good, and that they had fought back the Israeli incursions and put a stop to them. The Egyptian president informed his Syrian counterpart of Egypt’s position vis-à-vis the Soviets.

After this talk with the Syrians came the report of the Egyptian president’s envoy to the Syrians: he assured the president that they were going ahead with military actions. I must admit that the diaries reveal, for the first time, my concerns about the Soviets’ position, and doubts about the Soviets held by many Egyptian statesmen. There were also some concerns and misgivings about the Syrians’ vision of, and objectives for, the war. The two Arab parties had been coordinated militarily but their diverging political positions urgently needed coordination.

The Soviets’ attempt to convince Sadat to accept a ceasefire, in my estimation, was due to their fear that the US might throw its full military might into supporting Israel, leading to the latter’s military victory—a blow to Soviet interests. When Sadat rejected their position outright, they felt a need to salvage their relationship with Egypt, despite any doubts, distrust, or suspicion. Soviet leaders thus decided to re-supply both the Syrian and the Egyptian armies, making up for their losses. However, what is certain is that Soviet actions reflected the fact that the Soviets preferred the Syrians over the Egyptians—or, at least, reflected their perception that the Syrian army was in need of immediate and urgent support and assistance, while the requests of the Egyptian army evidently constituted a secondary priority.

According to my diary, the Soviets, having made the decision to provide military supplies, moved a number of Soviet armored vehicles to the port at Odessa, loaded with tanks to be delivered to Soviet ships for immediate departure. Confirmed intelligence available to us at the time indicated that the Soviets sent four hundred Soviet-made tanks between October 8 and 11. These arrived in Latakia on October 11 and were immediately offloaded for use by the Syrian army, which had lost a large number of tanks. The Israeli air force also stayed away from the Latakia port at that time, due to strongly worded Soviet messages that any attack on Soviet ships en route to Latakia or in the port would have serious consequences.

Meanwhile, Egyptian armed forces were awaiting the arrival of a large number of missile batteries, which Israel was destroying heavily to render the Egyptian air defense vulnerable and make it fly blind. We were also expecting a shipment of Volga longer-range missiles for the defense of our forces deep in Sinai. Doubtless those who planned the Egyptian attacks had timed them so as to ensure Egyptian ground troops would never find themselves outside the defenses afforded by their umbrella of anti-aircraft missiles. The plan also ensured that Egyptian capacities would not be exhausted in possibly destructive clashes with Israel. Herein lay the importance of air defense to the philosophy of battle; President Sadat’s contacts and meetings—revealed by his meetings with the Soviet ambassador—focused on the need for this type of supplies in particular.

The moment to develop the attack was approaching. It was the moment we had all been waiting for, ever since our troops leapt onto the Bar-Lev line and destroyed it, rebuffing the dispersed counterattacks. Some felt we were leaving it rather too late; others understood the need to completely secure the troops against Israeli airstrikes, as mentioned above. In the early days, the Israelis concentrated on Syria, which received the opening strike of the battle. In the estimation of some at the time—myself among them—the Israeli focus on Syria defied all logic, since experience with this kind of conflict imposes on rear-echelon strategists to concentrate on the stronger power, the one with the greater capacity to defeat them, and only then to turn their attention to the weaker and less dangerous attacker. What was certain, however, is that Syrian armored vehicles drawing near to Upper Galilee imposed another strategy on the Israeli military leadership, namely to put Syria first. This was the source of the predicament in which the Syrian army found itself, which led to extreme sensitivity on the part of the Soviets—mentioned above—and the Syrian leadership. It also imposed on Egypt a move toward developing the battle, with an attempt either to reach the Sinai passes or to try and relieve the pressure on Syria with large-scale ground operations on the Egyptian front.

This brings us to the second crisis of the war. In parallel with the intensification of battle, Sadat’s communications with foreign leaders intensified, as did his proactive diplomatic activity, even as the armies clashed. It may be useful here to glance at my diaries for Friday, October 12, and Saturday, October 13. They largely reflect the delicacy of the situation, which we had already intuited. At 0150 hours on Friday, I wrote:

Syria’s military situation not good at all. Israeli armored vehicles advanced toward Damascus, in a five-kilometer penetration. The Syrians are attacking violently to repulse the intrusion. What will happen if Syria withdraws from the battle? We will of course keep going. Have we lost the initiative? Perhaps. We’re still waiting for the Volgas. The Soviets tell us they should arrive today or tomorrow. Clearly the battle will last longer than I originally imagined. Perhaps another fifteen days. The Israelis will soon focus the thrust of their efforts against us. The president is pressuring America via the oil-producing countries of the Gulf, especially Saudi Arabia. Also through continuing talks with Kissinger via Hafiz Ismail. We have warned the Americans that if the Israelis keep bombing civilian targets in Egypt, we will retaliate in kind. This is our second warning.

The Soviet air bridge to Egypt has been going on since yesterday. Will we have time to use the new missiles? Will we receive enough of them to make a meaningful difference? I hope so.

Additional bridge equipment has arrived. I imagine that the enemy will attack us fiercely soon. We will fight them off and defeat them, then move forward under missile cover; in fact, we might move forward much sooner, perhaps even before the enemy’s major attack.

The situation is delicate; I don’t think it is yet critical. Perhaps in two days’ time. We are faced with three Israeli fighting groups. Advisor Hafiz Ismail is exasperated by the Syrian situation and has become extremely short-tempered.

The crossing of the Egyptian canal by Egyptian forces and Syria’s attack on the Golan Heights. Based on a map published in TIME magazine, October 1973.

My entry in the early hours of Saturday, October 13, focused on Syria:

The Syrian counterattack has managed to fend off the Israeli penetration. Everyone is optimistic. Syria will repulse it.