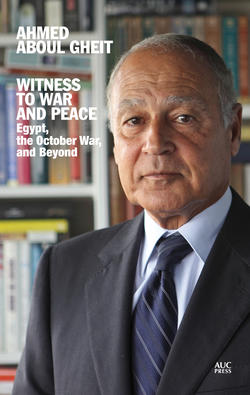

Читать книгу Witness to War and Peace - Ahmed Aboul Gheit - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOREWORD to the Arabic Edition

Ambassador Mohamed Assem Ibrahim

Former Egyptian ambassador to Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, and Israel

Dear Reader,

It is a great honor to introduce you to this book, a true achievement. In writing this, I have a threefold responsibility: to the reader, to this profound and multidimensional book, and finally, to the author, a lifelong friend.

I shall start with the author. For seven years, we knew him as the foreign minister of Egypt. Preceding this were four decades of loyal service to the diplomatic corps, a steady rise through the ranks culminating in his position as the most senior ambassador and Egypt’s permanent representative to the United Nations.

I met Ahmed Aboul Gheit more than half a century ago. We started secondary school together, and met regularly at the Armed Forces Officers’ Club—our fathers were both officers, his in the air force and mine in the artillery corps. We shared a passion for public affairs that started in 1958. Like all of our generation in that tumultuous era, which started with the 1952 revolution, then witnessed the British withdrawal, the nationalization of the Suez Canal, followed by the Tripartite Aggression in 1956, the union with Syria, and other events that are common knowledge, we dreamed of a new dawn for Egypt’s role in the world, a date, as the phrase goes, with destiny.

Ahmed Aboul Gheit was, and still is, passionate in his love for his country, confident in his abilities and in the iron will of the Egyptian people, strong as the granite out of which the statues of Ancient Egypt are carved, still standing today in the central squares of the world’s greatest cities. He bears an unconcealed enthusiasm for history and riparian civilizations in Egypt, Iraq, and China. It was Aboul Gheit who first introduced me to historian Arnold Toynbee, when we were no older than fifteen. We spoke of Ancient Greece, and the struggle between warlike Sparta and civilian-spirited Athens, and how Athens finally won a decisive victory over Sparta, even though the latter had emerged victorious in the Peloponnesian War. We spoke of the mechanisms of the rise, decline, and fall of empires, and the cycles of Egyptian history over four thousand years; we discussed theories of war, and the great military philosophers; we spoke of battles that changed the course of history and the reasons for them, how they were managed, and their ultimate outcomes and consequences, how peoples and armies related to the leaders of thought and literature, and the role of leadership abilities, especially in crisis.

Ever since I have known him, Ahmed Aboul Gheit has been an early riser, often before five in the morning. Never one for late nights, he is also the first to leave our company for bed. I doubt that he has ever worked less than twelve hours a day, and very frequently longer. Above all, he is loyal: to his family, to his friends, and first and foremost to his country. He has made no secret of his ambition. In every position he has held, he has been a whirlwind of intelligent activity, hard to keep up with in both quantity and quality. It was only natural that he be assigned the most important of posts. When stationed in Cairo, he was needed at the Foreign Ministry, at the office of the national security advisor, on the prime minister’s staff, and even became assistant to the minister for office affairs twice in succession. In New York, he served three tours of duty, in addition to Moscow and Cyprus. He was ambassador to Rome and head of the Egyptian diplomatic mission to New York.

Step into his house and you will be overwhelmed by the sheer number of encyclopedias and reference books. He has conversed with the cultural elite in Cairo and in the world capitals where he has worked, and amassed an incomprehensibly vast number of friends and acquaintances, with an exceptional memory for detail whenever he meets any of them again.

During his university years, he was greatly influenced, in my estimation, by the writings of Winston Churchill. He has left no biography or memoir unread: Mao Tse-Tung, Gandhi, Lenin, Ataturk, even Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin, and all the Second World War Allied leaders. These rivers have all flowed into Aboul Gheit’s personality, which has matured with time and experience. One of our conversations that has remained etched into my memory is when President Nasser decided, in May 1967, to close the Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli maritime traffic. “I’m afraid,” he said to me, “of Israel launching a raid and invading Sharm al-Sheikh before we can fully mobilize in Sinai. They’ll want to secure their shipping routes to Eilat,” which President Nasser had effectively closed with his blockage of Aqaba.

“If there is a confrontation between the two armies,” I replied, “I’m very much afraid it will be 1956 all over again.”

And so it was. Neither of us was yet older than twenty-three.

A full year before he left the Foreign Ministry, Aboul Gheit began to think of compiling his copious notes and diaries as a contribution to our national memory, a gift to the generation about to assume responsibility in the near future. He was aware that a great deal of our history, both in Egypt and in the Arab World, is being written by others. Our own views of history, our archives and record-keeping, our laws on declassification of documents, and so forth, are woefully inadequate for any state in this century. I need only mention the fiasco that occurred when we were trying to find the international treaty demarcating Egypt’s borders with Palestine. We simply could not locate the thing in our files, and were reduced to getting copies from Turkey and the United Kingdom in order to refute Israel’s (invalid) claim to Taba. The original copy was in Cairo, that much we knew; our filing system was just so outdated and unworkable that it was impossible to find.

For these reasons, and more, Aboul Gheit has decided to put pen to paper, giving today’s and tomorrow’s readers access to his information and eyewitness accounts. This may help bring the Egyptian point of view into the picture.

I have some observations on the book you are holding, having had the opportunity to read it before publication. The author has chosen the title, Witness to War and Peace; however, I believe that he was not only a witness but also an active participant, as you may note in the coming pages, over four successive eras: first, the period from the June defeat to the decision to engage in large-scale military action; second, the time of armed conflict; third, the interventions during the ceasefire between the end of war and the commencement of peace; and finally, the peace process.

The book is entertaining, although it is documentary in nature. Aboul Gheit’s style is lucid and his phrases well-turned, although never too informal. This is a book that is hard to put down. It unpacks weighty secrets with literary flair and a human touch, revealing the untold story of the saga of war and peace.

Most important, Aboul Gheit has meticulously documented his experiences. He has transcribed speeches and copied documents; he has noted the names, dates, and locations of every action, with exemplary objectivity and neutrality. This professionalism stems, no doubt, from his previous readings of the greats.

One thing that is almost unique about Aboul Gheit among his peers is this: he does not pretend to know what he does not know. He has only documented what he has personally taken part in or witnessed firsthand. He has claimed far less credit for himself than is actually his due. He also affords the reader every opportunity to differ with his conclusions, as evidenced by his clear demarcation between documentary evidence and his own (or indeed others’) personal opinion.

You may also notice that he tends to look at the big picture—not the star but the constellation. He analyzes Egypt not in a vacuum, but in relation to its position on the wider world stage. This by no means indicates any inattention to specifics. In other segments, when he analyzes the behavior of leaders in times of political and military crisis, or in the segment on relations with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and its gradual introduction to, and acceptance into, the world political arena, he goes into minute, almost microscopic, detail.

This may be one of the most neutral and unbiased books originally written in Arabic in its description and analysis of events, even taking into account the sometimes conflicting human emotions and reactions that accompanied them. There are two main paths in the book: first, the conviction that the process of war and peace finally led, despite all the issues and criticisms, to banishing the defeat of 1967 from Egyptians’ hearts and minds. The second is his unwavering love for anything and everything related to the nation of Egypt: its people, its armed forces, and its diplomatic corps, which he highly appreciates, knowing the acumen of its leaders.

This is a central reference for any student of this period of our contemporary history. I promise you hours of edification and entertainment.