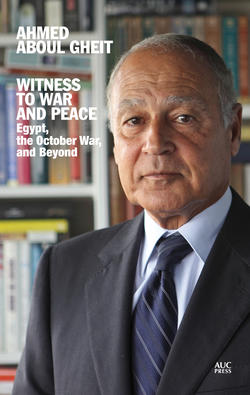

Читать книгу Witness to War and Peace - Ahmed Aboul Gheit - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6 The October War: Military and Diplomatic Efforts, Coordinated

Years ago, I read Sir Winston Churchill’s quote about Admiral John Jellicoe, whom Churchill famously dubbed “the only man on either side who could lose the war in an afternoon.” Churchill was the head of the Royal Navy during the First World War until he left his post in 1916, after Britain’s failure to take Gallipoli, and the attempt to penetrate the Dardanelles. Jellicoe had been the admiral of the Royal Navy in the Battle of Jutland—the British navy’s first and last clash with the full force of the Imperial German Navy’s High Seas Fleet, in 1916. The British navy was unable to achieve a decisive defeat and destroy what was, after all, a navy comparatively lacking in experience and weaker in ability, under the leadership of Admiral Scheer. The battle was over in a day. One of history’s greatest naval battles ended in British losses, in terms of main ships, greater than those Germany sustained.

The battle was the subject of much discussion, spoken and written, after the fact, and the discussion did not wane even after the end of the First World War in 1918. Much of it focused on the odd reserve of Admiral Jellicoe, and asked why he had not invested his far greater superiority in a more aggressive approach. This was the subject of Churchill’s famous quote, giving Jellicoe his due. The defeat of the Royal Navy on that day would have doubtless led to a complete defeat of Great Britain in the fierce and furious battle with Germany on the European continent.

I have my reasons for introducing this chapter with a reference to the Battle of Jutland. Egypt, I always felt, burdened Ahmed Ismail Ali, commander in chief of the Egyptian armed forces, with heavy responsibilities. The man shouldered these with aplomb, accurately estimating the precise abilities of our armed forces and what they were capable of doing. He also grasped the required objectives and the ways and means of achieving them, and finally, the methods that could be used to motivate the armed forces and their main branches to achieve the military objectives—and thence the political objectives—of war. With his depth of experience and wisdom, Ahmed Ismail Ali was keenly aware that Egyptian military operations across the Suez Canal were not only about destroying the Bar-Lev line. Breaching this heavily guarded line, starting with its broad water barrier, with all its stations and fortifications, was not an easy task—certainly as daunting a challenge as anything faced by First World War soldiers. Ali knew that beyond this, his mission also included taking the strip that extended all along the east bank of the Suez Canal, striking back against Israeli counterattacks; securing an end to armed confrontation; and ensuring the presence of capable, effective, and dominant Egyptian forces on the ground in Sinai itself, even if only on a strip as narrow as ten to fifteen kilometers. This would be the proof that Egypt had destroyed the theory of Israel’s security, as immune from any outside intrusion on the Bar-Lev line, and had the means to impose on Israel and the US the necessity of moving toward a political settlement.

Hence Ahmed Ismail took control of all his forces with an iron grip. He absolutely forbade any of his main Second and Third Army forces from hastily succumbing to the temptation to leave the bridgeheads of the five infantry divisions. Indeed, he fought hard against any notion of making an immediate move to exploit the preliminary opening success of the battle, namely the destruction of the Bar-Lev line. Instead, he sustained his infantry divisions’ strategic focus on defeating all the armored counterattacks, and maintaining a presence on the lines that had been established from the start to accomplish Egypt’s preliminary military objectives and the longer-term strategic and political goals of its military action.

Egypt’s early success came at a price far lower than that estimated by the military and political leadership. This placed Ahmed Ismail Ali under pressure: he was urged to consolidate his successes by allowing, indeed directing, his forces to Mitla and Gidi, the two main passes deep inside Sinai. Some also mentioned in their postwar analyses that Golda Meir was shocked by the capitulation of Moshe Dayan, then minister of defense, and General Shmuel Gonen, chief of the Southern Command. In a stormy meeting on October 9 at the Southern Command Base in central Sinai, they asked Meir to look into withdrawing the Israeli forces standing against the Egyptians deep into Sinai, behind the Sinai passes. Meir, however, absolutely forbade it. She decided to appeal to U.S. officials, asking them to move immediately to supply Israel with all the weapons and ammunition it needed.

Subsequent years have revealed that, at the time, there was some disagreement in Washington between the Department of Defense and the State Department about the Arab reaction, specifically the Arab supply of oil to the western world. The matter was resolved in favor of the State Department, led by Kissinger, who said that Soviet weaponry could not be seen to vanquish U.S.-made armaments. America’s decision was made: Israel would receive everything it needed and more, and every U.S. naval and air resource would be pressed into service to achieve this end.

I remember here—in response to those who say that the attack should have been developed starting October 10, after Israel’s armored counterattacks had been repulsed—that Ahmed Ismail Ali was well aware that the Soviets had no desire for the Arabs to breach the ceasefire, and had been against it from the start. Egypt and Syria had succeeded in putting massive strategic and political pressure on the Soviet Union to supply them with weapons, enabling the Egyptian army and air force to build their capacity, especially between October 1972 and October 1973. Indeed, it would not be going too far to say that Egypt succeeded not only in giving Israel and the west the impression that it was militarily unprepared, but also in fooling the Soviets, who imagined that its cadres and leadership were unqualified to put these weapons to use in the hands of Egyptian soldiers. It follows that they imagined Egypt’s commander in chief had no wish to find himself—amid the exigencies of the battle he was being urged to wage—at the mercy of the Soviets for essential munitions and supplies. This was the source of his conservation of forces, resources, and efforts. This was the controlling ethos of the Egyptian position from preparation for battle until it finally drew to a close.

Reports from our embassies and diplomats on their discussions with their western counterparts indicated—from my reading of them—that everyone expected the Soviet weaponry in our possession to become obsolete within two years, and that it was hard to imagine the Soviets agreeing, or being persuaded, to make up the Arab shortfall by supplying us with new state-of-the-art aircraft, tanks, and heavy artillery. I am convinced that Ahmed Ismail Ali realized that losing his army a second time, or repeating the defeat of 1967, would be the fatal blow to Egypt. Israel would of course count this as a success, tightening its hold on Sinai for decades, perhaps generations. This explains his clear circumspection and iron control over the army, and his refusal of the temptation of development and its possible merits. He could see only too well the downsides.

National Security Advisor Mohamed Hafiz Ismail, in his analysis of this viewpoint, writes in his book on Egyptian national security and the October War:

With the completion of the armed forces’ direct objective on 10 October, I must indicate that I—in talks with Lieutenant-General Ahmed Ismail Ali before the war—am aware that he had no intention of moving in as far as the mountain passes. The instructions of the ops center of General Command were that the objective was to take the passes; however, these were meant to motivate the junior leadership to keep going, during the bridgehead-building stage, until they reached the direct objective intended by the army.

I must reaffirm my conviction that when a state and/or society takes the path of armed conflict, it is the duty of diplomacy to safeguard the successes of military action and not allow them to be held back, and also continually to work toward finding opportunities to achieve the ideal strategic and political situation when a ceasefire should occur. This, in my estimation, was the chief preoccupation of Hafiz Ismail and his team.

The Egyptian army mobilized and continued with its preparations and fortifications on the east bank of the canal, until the first crisis of battle. We continued calm diplomatic efforts, while holding our breath in anticipation. We were waiting for the moment when, in our estimation, Egypt would achieve its military objectives, at which point we could work toward reaping the political profits. From the outset, the deterioration on the Syrian front imposed on Egypt the need to relieve the pressure on the Syrian army by drawing some of the main Israeli forces to the Sinai front. However, the Israelis—starting on October 12—were already pushing a great many of their main units toward Sinai, as shown by an Egyptian reconnaissance report by elements spread out deep within Sinai behind enemy lines. On that same day, large numbers of mobile bridging equipment were observed, indicating Israel’s intent to cross the Suez Canal.

I was extremely puzzled when reading this report, presented to Hafiz Ismail. How could the Israelis imagine that they would succeed in displacing the concentrated Egyptian forces in their path? How would they deal with the armored and mechanized Egyptian divisions stationed west of the Suez Canal, close to the waterway, the Fourth and Twenty-First Armored Divisions, and the Sixth and Twenty-Third Mechanized Infantry Divisions? In any case, this information clearly did not faze President Sadat, who insisted on developing the attack, nor did it affect the plans of the General Command under his direction. On October 13, several of us learned in the office of Hafiz Ismail that a heated argument had taken place between commander of the Second Army, Major-General Saad Ma’moun, and General Command in Cairo. Ma’moun, for long hours, opposed the concept of developing the attack, in order to preserve his forces and the balance of the army on both sides of the Suez Canal. While arguing with General Command, he had a mild heart attack, which forced him to step aside. Major-General Saad Khalil replaced him as the head of the Second Army.

My diary entry for Saturday, October 13, 1700 hours:

Our forces are currently faced with three main fighting groups. In my view, Damascus cannot fall. The Israelis will not attempt to enter into an Arab city of such a size and population. Syria will fight off the penetration.

I added in the diary that the British ambassador had awakened President Sadat at 0400 hours on October 13 to give him a message from the British prime minister. The message was that Secretary Kissinger had asked Sir Alec Douglas-Home to make a proposal to the Egyptians, the gist of which was that Israel would not refuse a ceasefire along the current battle lines if Egypt was amenable to the idea. Sadat refused this overture, in the absence of a consolidated political horizon for dealing with the conflict and its political aftermath.

The Soviet ambassador had also contacted the president directly a few hours earlier, in the early hours of October 13, calling upon him to consider a cessation of hostilities. In the diary for the same day, I wrote:

The Soviets are worried about their relationship with America. Also, they must be concerned about the situation with the regime in Syria. According to the record of the call made by Mr. Abd al-Fattah Abdullah, minister of state for cabinet affairs, the president asked that any ceasefire be accompanied by an agreement on a plan for the Israeli withdrawal from Sinai, including a time frame for the withdrawal, and that a peace conference be held, attended by the two superpowers.

I also wrote this:

The president has an admirable clarity of vision. He sees

• That Israel is attacking Syria for political, not military ends—for future negotiations. Israeli military officials are seeking some appearance of victory to conceal the strategic shock they have undergone.

• The main front is the Suez Canal. It is this that will decide the outcome of the conflict. The battle now is Egypt’s, not Syria’s. The turning-point will be the Egyptian army’s success at striking the Israeli army in Sinai, and foiling the latter’s plan of attack against the Egyptian army.

The points that Sadat addressed with the ambassadors of both the Soviet Union and Britain were the same ones Hafiz Ismail covered in his first written communication to Secretary Kissinger on the evening of October 7: “Egypt’s unchanged goal is achieving peace in the Middle East, not a partial settlement. It follows that Israel must withdraw from all the occupied territories, at which time Egypt will be prepared to take part in an international peace conference under appropriate supervision.”

Messages began to flow thick and fast between Hafiz Ismail and Kissinger. On October 9, Ismail sent a message saying that Israel must withdraw to the June 5 borders before a peace conference could be held to set out the details of an agreement for a permanent peace. Egypt, the message said, had no objection to an independent international presence in Sharm al-Sheikh to ensure the freedom of international navigation in the Straits of Tiran and Sanafir. With that, Ismail and Kissinger began to set out their positions in more detail. It became clear, however, that the American side was still somewhat evasive and frequently prevaricated to waste time in anticipation of some Israeli military success on the ground. For example, Kissinger’s messages began to ask what Egypt meant by withdrawal from “all” the occupied territories, whether such a withdrawal would precede or follow the peace conference, and so on.

A new message from Hafiz Ismail reiterated his vision, the one conveyed to Secretary Kissinger at the start of the clashes. There were many considerations for the position in which President Sadat found himself, and Hafiz Ismail was clearly committed to carrying out the president’s instructions. It was certain, however, that Egypt’s distrust of both Israel and the US weighed heavily on the ultimate decision-maker, causing him to refuse an end to armed conflict, especially given his concerns that the US and Israel were only seeking a temporary or tactical ceasefire, after which Israel would resume its military operations against us. What was also certain was that Egyptian political leaders discussed the option, especially given the escalating Soviet pressure for a ceasefire. Hafiz Ismail’s message, referenced above, which he later published in his memoir, Amn Misr al-qawmi fi ‘asr al-tahaddiyat (Egypt’s National Security in the Age of Challenges), mentions that Dr. Mahmoud Fawzi, the foreign minister, feared a negative reaction from the ranks of our armed forces if they were ordered to stand down at a time when Israeli forces were suffering heavy losses, yet still advancing toward the east bank of the Suez Canal. Fawzi proposed that Israel announce its respect for the neighboring Arab countries’ full sovereignty over their own lands, and officially demand a ceasefire. The fact is that Hafiz Ismail’s writings were very much in line with my own thoughts at the time. I had been following all the developments via the messages and minutes of Abd al-Fattah Abdullah, as well as other documents and telephone recordings.

Israel’s counterattack. Based on a map published in TIME magazine, October 1973.

Egypt moved to develop the attack. The pause for mobilization from October 6 to 13 would have lasted until the end of armed hostilities had it not been for the situation in Syria, which imposed the need for a move eastward. I learned that the development of the attack, intended to relieve the pressure on Syria, at President Sadat’s insistence would start late on October 13. However, it was postponed to dawn on October 14. My diary on Saturday at 1700 hours states:

An American SR-71 reconnaissance aircraft flew over the Nile Delta and Cairo, to the Suez Canal and Sinai, and left via Arish on the way back to where it had taken off from, an American air base in Europe. It was at an altitude so high that it remained out of range of Egyptian fighters and anti-aircraft missiles.

This reconnaissance flight strongly affected battle developments: the aerial photographs America gave to Israel revealed that the main Egyptian units stationed in reserve west of the Suez Canal had crossed to the east bank, which meant intent to develop. The images also revealed that the west bank of the Suez Canal was now largely empty of main heavy forces. The enemy was thus prepared for our strikes. The battle moved into an unprecedented, delicate, and critical phase.

Our forces launched the developing attack on October 14. The attack paused in the evening after our forces had sustained heavy losses—between two hundred and twenty and two hundred and fifty tanks and armored units. These were no doubt serious losses. In my diary on Monday, October 15, at 0700 hours, I wrote:

It is clear that our attacks have ceased. This will have serious consequences for the battle. It is also important not to abandon our initiative over the enemy, or we will be struck without mercy. We must keep the pressure on with active attacks.

Years later, I noticed that Hafiz Ismail had come to the same conclusion, which he laid out in Amn Misr al-qawmi fi ‘asr al-tahaddiyat (Egypt’s National Security in the Age of Challenges):

The attack launched by our forces in the daylight hours of October 14 achieved its objectives even before the forces left their bases at the bridgeheads. Since October 13, Israeli attacks on the Golan front had ceased, and the threat to Damascus had been averted. However, with the end of the development battle on the evening of October 14, the Egyptian military command had exhausted our forces’ energies, proving the advantage of the initiative we had achieved since October 6. The fact is, however, that this initiative had been slowly eroding ever since we stopped advancing in favor of pausing for mobilization, thus handing the initiative, ultimately, back to the Israeli military command.

I am completely convinced that Ahmed Ismail Ali and the military command that faced this extremely difficult and delicate situation on the evening of October 14 made the prudent decision. By pausing the attack, they spared more heavy losses of their forces needed for the future of the battle, and to deal with the Israeli counteroperations revealed by reconnaissance and observation seventy-two hours earlier, that is, on October 11 and 12.

Hafiz Ismail continued his analysis of the events of October 14:

The matter merited a struggle to re-arm and rearrange our units that had been in battle, reassembling and redistributing them within the coming twenty-four to forty-eight hours, in preparation for the next stage of enemy operations, which was of course inevitable. We needed to take into account that the failure of the Egyptian attack on October 14 was the real starting point of the Israeli counterattack.

Hafiz Ismail’s points and anaylsis were not unfamiliar to the Egyptian commander in chief’s. The president worked to obtain the maximum military support necessary for this upcoming critical stage of armed conflict. My diary for 0700 hours of Monday, October 15, noted that, “Egypt has obtained two hundred tanks from Yugoslavia. They are slated to be sent to the port of Alexandria in a few days. There is also talk of tanks from Morocco, Algeria, and Libya.”

I opened this chapter with Churchill’s reference to Admiral John Jellicoe in the First World War as “the only man on either side who could lose the war in an afternoon.” Ahmed Ismail Ali, the commander in chief of the Egyptian armed forces, likewise could have lost the war in the afternoon of October 14, 1973, if he had insisted on pushing his attacks forward to the mountain passes, which had been the goal of the original plan.