Читать книгу The People’s Paper - Christopher Lowe - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

TRANSLATION AND ENGAGEMENT: JOURNALISTIC AND NATIONALISTIC CONTEXTS

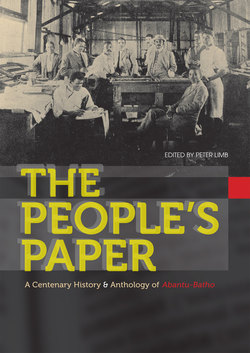

ОглавлениеIn times of change, as Benedict Anderson and others have shown, newspapers could influence or connect to the public sphere, politicise people and interpret new ideas; in this way they could be ‘distinctly subversive’. They could also show the way to alternatives to the status quo.104 Abantu-Batho would do just this, posing alternatives to white rule in liberalism, African nationalism, socialism and Garveyism, and so helping ignite new African identities and dreams for the future. Like journalists the world over and despite their lack of training, its editorial staff were skilled ‘word weavers’ somewhat akin to literary writers and carriers of an oral tradition that had been gradually incorporated into a press format.105 Indeed, one editor, Grendon, was an accomplished poet and, as Figure 3 (and Jeff Opland’s chapter) intimates, another poet, Nontsizi Mgqwetho, may well have been a fleeting staff member. In this section I focus on translation, engagement and nationalism; in chapter 11 I elaborate the journalistic aspects of the ‘People’s Paper’.

Editors, lacking access to expensive white commercial news agencies, developed their own processes of gathering news, locating and maintaining sources, selecting and laying out stories, and writing for a wide audience. In doing so they forged distinct relationships to politics and to modern cultures, and played a major role in building a new national identity. Simultaneously, they maintained old identities and links to indigenous cultures, for implicit in a multilingual structure was the dilemma of how to communicate in the vernacular and retain solidarities forged on regional or ethnic bases while at the same time constructing African nationalism.

Translation played an important part in these processes. With four or five languages, there may at any one time have been the same number of independent editors. Some articles appeared in different versions that offer variant interpretations of the same event (see Paul Landau’s chapter in this volume), but what exactly went on is only partly known. One process in play was cultural resistance. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o argues that close examination of colonialist pressure on African cultures can reveal pride in African languages; Lorna Hardwick shows that developments in translation allowed classics to be appropriated by imperial subjects to help challenge colonialism and represent histories of African resistance.106 What might linguistic analysis of Abantu-Batho reveal?

The paper was attempting a creative adaptation of language and culture aimed at socio-political transformation. In his chapter in this volume, Jeff Opland shows that poets used its pages to interpret and encourage such transformation, and we can see this engagement with regard to the vernacular and adaptation of works of English literature such as those by Shakespeare.107 There was a sort of hierarchy of languages in Abantu-Batho. English tended to be relegated to the middle pages as ‘The Empire Writes Back’, although it may have served to bind some readers. A column count using random samples of complete issues from 1928 to 1931 suggests attempts to balance languages, but that Sesotho and isiZulu may have been dominant, at least in letters and advertisements, which is logical, given the main audience on the Rand. The ‘languages question’ may not have been fully settled at the start. In 1912 Kunene (backed by Plaatje) had earlier proposed the new SANNC adopt an African language name, such as Imbizo Yabantu (Bantu Congress, or Congress of the People),108 and contemporary African newspapers bore vernacular names. In December 1912 the precise mix of languages was still ‘a matter for discussion’.109

Publishing in so many languages aimed to reach wide audiences, and part of this was undoubtedly conveying the political message(s) of Congress. Undoubtedly, the paper sought to mobilise politically both kholwa strata and chiefs, and at times it also published direct appeals to workers and women. However, these messages were by no means singular, as was evident not only in the differences among provincial Congresses, but also the rise and fall of political leaders over a short span of time. There was a marked difference in the politics of the moderate John Dube and the radical Josiah Gumede. The coming and going of individual editors, from the moderate Saul Msane to the more radical Daniel Letanka, also lent variety to the political opinions expressed. As we explain in chapter 1 of this volume, political pluralism even extended to accommodate views not in support of Congress. Questions arise here that we cannot yet answer. What did it mean to translate into a coloniser’s language, and if an educated black stratum was now reading in English, what does this say about the problems and confusion engendered in building a new African nationalism?110 There are also translational problems of the archaic orthography of language, the use of metaphors, wordiness and untranslatable terms.111

Journalism history has drawn profitably on cultural and comparative studies of the media to highlight and weigh alternative readings of the press, whether as a reflection of or ‘constitutive medium’ of society.112 Journalists everywhere produce ‘news’ and engage with society and ideologies.113 In settler societies such as South Africa print journalism played a crucial role in creating real or imagined communities of readers and connecting them with one another across town and country, into a nation and to rulers,114 and more widely to engage imperial and other international or diaspora networks. The medium of print in settler societies with stunted indigenous bourgeoisies, such as South Africa, played a pivotal role in developing nationalisms and engaging the state.115

Abantu-Batho was a weapon that allowed engagement more on African terms and much more so than in deputations or the white press. A newspaper was impersonal, often anonymous via collective authorship,116 varied in views and able to use the ‘freedom of the press’ to push the envelope of criticism. Abantu-Batho used vernacular languages to change the linguistic terrain or discourse, although censors scrutinised its columns. If reaching a limited audience, it was important in instituting political engagements on better terms for Africans and helping make these encounters more flexible and potent. It ‘crossed the line’ between polite deputation and political resistance, usually seen as starting only from the late 1940s, and in this sense helped prepare the ground for popular resistance. It did this by broadening the terms of engagement to include solidarity with different classes, women, and other African peoples, and by reinserting into discourses African notions of politics (as around chiefs) and new hybrids of African and Western politics (such as Congress itself, a very African version of a parliament).

All this is not to say that other black newspapers did not also aim to speak on behalf of ‘the people’,117 or those parts of the population with whom they particularly identified. Imvo, Ilanga and Umteteli, for example, also sought such a mantle, and the latter two had close connections with some parts of the Congress movement. Umteteli (like its white mining backers and the white government) was strident in its rejection of Abantu-Batho’s claim to represent ‘the people’, as demonstrated in chapter 7 of this volume. The frequent reprinting of one another’s articles in the first years of Abantu-Batho points to a certain camaraderie among the black press. Moreover, some Congress provincial branches developed their own organs and, as Chris Lowe observes in his chapter, in its very early days Congress officials envisaged or recognised multiple organs; although the term, I suggest, might refer to credentialed papers accorded access to meetings rather than organisational organs.118 Nevertheless, Abantu-Batho claimed – and to some extent would succeed in building – a more intense national pitch. It cultivated a special, even intimate, relationship with Congress, from Seme’s initial dream of a united national voice to its 1919 confirmation of official organ status in the TNC constitution, to Gumede’s ‘nationalisation’ of the paper in the late 1920s.

Similarly, ‘the nation’ is also fraught with complexity and contestation, on which there is a vast literature that deconstructs the term and warns of the dangers of the abuse of nationalism. Suffice it to say that in this period of rising African nationalism Abantu-Batho played the central coordinating and consciousness-raising role, as discussed above. When I speak of ‘the People’s Paper’, then, I do so more to capture the meaning of ‘Abantu’ and ‘Batho’ (‘people’) to its editors, writers and audience, and not to suggest any kind of endorsement of nationalism as such. Even so, and as I and others argue elsewhere,119 national liberation was and is a key concept in South African politics.

The national dimension is more significant here than may meet the eye. Historians of the 1970s–80s searched for social histories in newspaper columns, moving on to the cultural sphere. The onset of digital newspaper archives now presents the tool, as John Nerone says, to begin ‘the reconstruction of the national conversation of previous ages’, aided by the distributed nature of the press via the recirculation of content through reprinting in other periodicals or by exchange, which may have been more useful in generating a national profile than subscribers.120 This is one way Abantu-Batho is now emerging from archival obscurity. Just as close monitoring by opponents gave it some credibility, the reprinting of content and its exchange to editors in other places, and the ability to search some of this content online has helped us recover more of this hidden archive.