Читать книгу The People’s Paper - Christopher Lowe - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CIRCULATION, PROCESS AND STRUCTURE

ОглавлениеStarting a newspaper with national aspirations in multiple languages dedicated to fighting the white supremacist status quo and serving a largely impoverished community was a monumental task even for one as ambitious as Seme. Couzens, citing S. M. Molema’s wonderful description of the multitude of composing, editing and printing tasks confronting Plaatje on Tsala ea Batho, published at the same time, reminds us that running a black newspaper was tough work at that time:210

There were no journalists or clerks; and Plaatje was the sole worker doing the job of three or four people besides being editor. He collected the post, opened and read letters … and kept records …. He read papers of other publishers and editors; Government gazettes and papers and translated all from English into Tswana and Xhosa. Using a typewriter he arranged all ideas and news, proof-read various communications and letters and after correcting, editing them sent everything to the printing presses. ... When all … were finally printed on thousands of reams of paper and folded properly, the papers were bound, addressed, stamped and sent to hundreds of subscribers.211

Abantu-Batho did have several editors and a small staff, but running it cannot have been easy, as an analysis of its circulation, structure and capital reveals.

In 1914 the price was 3d, and remarkably remained the same until the final issue in 1931, even in periods of declining advertising income. From 1915 the annual subscription of 12s 3d was constant until at least 1928. The number of pages was usually eight, sometimes six or four, comparing favourably with other black papers. Language composition varied; in January 1928, for example, less than one-sixth was in English.212

The circulation or reach of the paper was complex. In 1914 it was ‘on sale at all news agencies in the Transvaal’; by 1931, it claimed213 that it ‘circulates through agents Subscriber and news boys in every one part of the Union of South Africa including protectorates Rhodesia [now Zimbabwe], Belgian Congo [Democratic Republic of the Congo] and South West Africa [Namibia]. No voice reaches further.’214 There is evidence it did reach Rhodesia.

In 1913 it claimed a weekly circulation of 5,000 ‘in Natal and the Transvaal alone’, a number not disputed by The Christian Express.215 In a letter to De Beers in 1914 soliciting advertising for the African language columns, C. S. Mabaso, Abantu-Batho secretary, claimed the same number, adding that it ‘enjoys the full confidence of the native population throughout the Union’, with its parent company ‘well financed’.216 In 1920 and 1928 Abantu-Batho, probably exaggeratedly, claimed the ‘largest circulation of any Native Paper in South Africa’.217 Mabaso, still Abantu-Batho secretary in 1922, repeated this claim (adding ‘sub-continent’) when he wrote to the Government Printer tendering for a contract for state notices, claiming a weekly ‘average circulation’ of 10,000. Published in three African languages, it carried ‘matters of particular interest to and affecting the native population throughout the Union’, but was ‘not intended to introduce anything with a political significance at all at these meetings; the object is merely to introduce our paper to [the] native public and enlist their sympathy and support’.218

There is some proof of decline. Barney Ngakane, active in the TNC from 1921, recalled, ‘I got most of my inspiration’ from Abantu-Batho. He estimated that by the late 1920s circulation was only 1,000.219 This modest figure is roughly comparable with other contemporary black papers,220 but definite decline is evident from the late 1920s, when paid subscriptions dwindled to a mere seven in Natal,221 although that province was never its base.

These figures appear modest, but the paper’s reach must have been considerably wider than paid subscriptions from a poor community with low literacy levels. Moreover, the general circulation of the early black press was small. Inkanyiso yase Natal could boast 2,500 sales in 1891,222 Koranta ea Becoana only 1,000–2,000 across the following decade,223 with Tsala ea Batho rising from 1,700 in 1910 to 4,000 in 1913, and Ilanga 3,000 by 1931. All this was framed by a rising, but still slight, black literacy rate of 9.7% in 1921 and 12.5% in 1932.224 Even the stately Cape Times had limited circulation in the 1910s, which, however, would double to 22,000 a day by the 1920s.225 Thus, by 1934 the black press directly reached only an estimated 25,000 of 850,000 literate Africans. Yet it influenced the more politicised and with a mushrooming effect as people passed issues from hand to hand or recounted aloud stories from its pages.226 The ‘persistence of oral reading’ was ‘often a collective experience, integrated into an oral culture’.227

How wide was this reach? We know it was read out at some rural and women’s meetings, and circumstantial evidence that papers were passed around and read out suggests a wide geographic and class reach. If we presume that readers were chiefly educated, urban strata, then there are also reports in the paper on rural events and of correspondence, for example, from the Lichtenburg mines, suggesting that copies penetrated there. The close involvement of editors in protests on pass laws and wages suggests attempts to reach workers. As Switzer observes, Abantu-Batho ‘gained a considerable audience as a result of the sympathetic coverage it gave to African workers mobilising’ at this time.228

More broadly, that there were not different ‘African minds’, but rather links and intersections between literate and oral evident in vernacular papers of the day is argued by John Lonsdale for the Gikuyu in Kenya of the 1920s. He also notes that young nationalists used newspapers to assert their authority against elders and chiefs, but often in a way that still included an element of oral performance: ‘literacy made oral authority portable, transferable … and readers could convert … personal skill into public authority any time they read out [newspapers] or other texts in public.’229

Plaatje recounted how, as a boy, he was often asked to ‘read the news to groups of men sewing karosses under the shady trees outside the cattle fold’.230 Something similar happened with Abantu-Batho. In 1919 the anti-pass law campaign prompted Sibasa Sub-Native Commissioner C. L. R. Harris to comment that Abantu-Batho was circulating among domestics in Johannesburg; ‘the unsophisticated African’

subscribes to the native newspapers (I find that the circulation of the Bantu-Batho amongst domestic servants in Johannesburg is remarkably large) the columns of which are followed word for word and even read aloud to the illiterate. The political teachings of these columns give him food for further reflection, and gradually he is drawn towards some native organisation or other ....

A knock-on effect took place as political news from the Rand, now the centre of black politics, was heard by elders who began to ‘wonder why’ and ‘become suspicious’. Harris, as a good colonialist, was appalled by this questioning, but conceded that it marked the onset of modernity. He was writing just after the huge anti-pass laws protests for which Abantu-Batho acted as a fund-raising node. To appreciate the centrality of the Rand, ‘one should peruse some of the correspondence appearing in the columns of the Bantu-Batho’ and he stated that black ‘bodies have considerably extended their tentacles’.231 This wider reach then was surely part of Abantu-Batho’s audience, and the questioning by readers was its legacy.

Proof of a far wider reach comes from the reprinting of an Abantu-Batho story in The Colonial and Provincial Reporter of Freetown, perhaps from British-based networks of Sierra Leoneans through the London African Telegraph. This example even pre-dates the arrival in Britain of the SANNC delegation that liaised with that paper. It may also reflect exchanges of newspapers, since we do know that copies were received in Tuskegee and Fort Hare.232 There also was occasional reprinting of its stories in other newspapers, in its first years notably Ilanga and Tsala ea Batho, but also The International and Indian Opinion, although in later years, after it was tarred as a radical rag, this dropped away.

Regional distribution varied. The SANNC was then weak in the Cape, but Abantu-Batho boasted nine local agencies in the province in 1918, some via activists such as Samuel Masabalala in Korsten Village, Port Elizabeth. There were two other distributors in Port Elizabeth, two in Kimberley and Barkley West, and one each in Ndabeni, Butterworth, Grahamstown and King William’s Town. There were also distributors in other provinces. In 1923 a Mr Mngqibisa ran an Abantu-Batho Ltd agency in Benoni.233

Switzer calculated the average life of a sample of 30 black pro-ANC newspapers between 1912 and 1960 as only 27 months. He argued: ‘The ANC never had a truly national newspaper’; ‘even the militant African-owned protest press remained provincial in its audience if not in its outlook’, while ‘the quality of Abantu-Batho … cannot be assessed because virtually no issues have survived’.234 Over three decades later we can analyse a rather wider sample of the paper and draw on greater knowledge of regional ANC history. In the 1910s it had some presence in rural towns of the Transvaal, holding mass meetings to discuss the Land Act and passes, and developing branches in places such as Phokeng, Lydenburg, Spelonken, Volksrust, Heidelberg, Bethal and Waterberg.235 Government officials observed in 1919 that Africans in the southern Waterberg ‘read the newspapers and the discussions amongst Europeans, in and out of parliament, in which constant reference to the rights and opinions of the native population is heard’, and this ‘is making an impression on them’.236 Dan Motuba in 1917 commented that in Rustenburg district many African ‘men who receive news papers … are simply raging mad at’ the imposition of pass laws on African women.237 Abantu-Batho editors such as Seme, Mabaso and Mvabaza addressed meetings in such places, intimating that the paper probably made it there, or at least was read out; a detailed report on a meeting in the Waterberg between chiefs and the Secretary of Native Affairs was printed in 1917.238 An instance of impact comes from Barney Ngakane, a teacher whose parents were Congress members. He recalls that teaching in a village in Piet Retief in 1921 he became aware, by reading Abantu-Batho – ‘the one newspaper we had’ – of harsh new taxes and through the paper he was able to follow the course of protests and mobilise local opposition.239

In general, and especially in its first decade, then, we can assume that the paper exercised an influence that exceeded its official circulation for four reasons: the passing of issues from hand to hand or oral transmission of some of its content, its role as a catalyst of protest actions, its status as Congress organ and scrutiny by the state.

The paper’s structure had very specific features. Its symbol (until 1929) was a circle enclosing a shield backed by spears and knobkerries with two hands shaking in the centre.240

The masthead in 1914 carried the sub-title ‘The Voice of the Native Races of South Africa’. There were sections in isiZulu, isiXhosa, Sesotho and English. Frequency was fairly regular: it was published each week on a Thursday. The weekly edition may have continued at the same time that a bi-monthly special English-only edition appeared for February–March 1920, and perhaps the month before.241

There were ancillary publications – pamphlets and an Abantu-Batho Almanac that appeared in several editions, first in 1916, when it sold for 6d,242 and again in 1917/18 and 1922. The 1917 edition, favourably reviewed (a ‘pleasant surprise’) by Ilanga in February 1918, featured numerous fine photographs, including portraits of Seme, Mangena, R. W. Msimang, Mvabaza, Grendon, H. V. Msane, solicitors George Montsioa and Ngcuou Poswayo, the wives of Dube and of Plaatje, musician Reuben Davies, and Africans in the Orange Free State (perhaps at the ANC conference). Also featured were Abantu-Batho workers, the SANNC delegation, Rubusana, Jabavu, and Mapikela and the premises of the African Club.243 In 1916 Seme took D. D. T. Jabavu to a photographic studio to have his portrait taken for the Almanac.244 The iAlmanaka lika Bantu-Batho of 1922 featured presidents Marcus Garvey and Makgatho, W. E. B. Du Bois, J. E. K. Aggrey, Duse Mohamed of Egypt, and Shaka – names that may have suggested to a young Mweli Skota their inclusion in his African Yearly Register nine years later.245 Lacking the anti-ANC phobia of his father, a few years later Jabavu sent the requisite postcard-size letter to The Christian Express commending Abantu-Batho (along with Ilanga, Naledi ea Lesotho and Mochochonono) as a fine example of African success that had ‘stood for many years’.246

We know little of actual press operations such as design/layout, the daily work day, and how editorial decisions were made, although we have one (meagre) ‘subscription list’ from Natal, a list of shareholders, a few photographs of the press and staff (see the cover and illustrations), and details of distribution outlets and estimated circulation. The first editors had to invent and then maintain routines of production; plans for distribution; and relations with readers, backers, rivals and the state. The paper did use sellers or ‘paper boys’ – in 14 August 1930, it advertised for ‘[m]en, women, boys and girls of the African race’ to sell the paper, offering a ‘liberal commission’ of one penny on each paper sold – each copy cost 3d (this price never changed). And standing as a huge obstacle to the smooth operation of Abantu-Batho (and the entire black press) was the absence of access to news agencies. Either through lack of money to afford the pricey news feeds of professional agencies such as Reuters (see chapter 11 in this volume) or by the reluctance of such white companies to share data, black journalists had to find stories on their own or were forced to reprint what was in other papers.

There were campaigns to boost circulation. In 1915 Kunene organised a concert and touring ‘Native Choir’, aiming to build a ’10,000 subscriber’ base. It was ‘almost impossible to get our people to come to meetings in large numbers in order that we may be enabled to talk to them on the importance of reading newspapers and thereby know exactly what is going on’. So he added to the entertainment some lectures on the need to read papers and take out subscriptions.247 Letanka also organised concerts and choirs.248 A poster ‘Kufuneka 10,000 abafundi’ publicising a concert at Ebenezer Hall (see Figure 4) reveals Abantu-Batho Ltd as printers, publishers, booksellers and newsagents; it was incorporated in Natal with £3,000 capital; directors were Seme (Court Chambers), Chief M. Moloi (Amersfort), Rev. G. W. Nkosi249 (Waterval), D. S. Letanka (Court Chambers) and the late Prince Malunge; and founders were the Queen of Swaziland and Seme. At the concert, R. W. Msimang would be chairperson (and perhaps lecturer), with performances by the West Minstrel Troup of Johannesburg, Mick Mike Makgate (‘Baritone Profundo in the Rand’) and J. K. Maphison, ‘well-known comedian on the Rand’.

Such concerts were part of a burgeoning Johannesburg associational life including clubs and debating societies of which Abantu-Batho was a central part (see chapter 11). The paper’s managing company also was involved in other activities. Abantu-Batho Ltd printed a pamphlet by R. W. Msimang.250 Moffat Caluza, Congress stalwart and uncle to composer Reuben Caluza, was a printer on whom it could rely; his press at 137 Albert Street printed Msimang’s exposé of the effects of the Land Act.251

The location, staffing and structures of the newspaper were determined by Seme’s decision to base it on the Rand and the resources available to him. Abantu-Batho was edited in Johannesburg and had its own press in Sophiatown. Kunene wrote from there in 1915 that he was ‘too busy at our printing works here to come to town’.252 Personnel included printers, compositors and distribution staff, the last mentioned including the then ubiquitous ‘paper boys’ and newsagents. Serasengoe Philip Merafe from Thaba’ Nchu had worked as a journeyman printer at Lovedale, then on Mochochonono in Maseru. He accepted Seme’s invitation to work as Abantu-Batho’s ‘foreman machineminder’. Based in Sophiatown, he probably worked there between 1912 and 1914 before moving to Kimberley.253 Another compositor employed in 1916 had been trained at Lovedale the previous year, but by 1917 was in Cathcart.254 Grendon and Kunene, with printing experience, may have assisted, as might Mvabaza and Letanka with their press background.

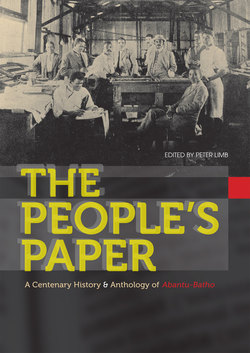

The editorial premises were in Court Chambers, corner of Rissik and Marshall Streets. By 1922 they had moved to 75a Auret St, Jeppestown, dubbed the ‘Abantu-Batho Buildings’. Skota recalled a Congress ‘Office off Joubert Street, corrugated iron like little hut’, perhaps also the Abantu-Batho premises.255 We know little of the editorial floor, how it operated or whether there was intervention from the managing director.256 Until recently, neither could we glimpse it. But now a previously misnamed probable photograph (see cover) reveals a galvanised or corrugated iron shed with Spartan furnishings, two layout tables and compositor’s tables with type, and a few chairs. While definite identification and dating remains tenuous, this may be the editorial premises (a printing press may be visible at the back) or more likely the print shop. The personnel we think we have identified (Letanka, Mabaso, Dunjwa and possibly Thema) and their clothing suggest a date of either early 1916 (given that in March 1916 Seme was forced to sell his galvanised iron buildings in Sophiatown, where the press also was located) or 1919.257

The capital (discussed in Lowe’s chapter in this volume) seems initially to have comprised shares worth £3,000, plus some cash. In 1919 state snooping disclosed that Seme remained managing director of the paper, run as a limited liability company of 25 originally issued and other, ‘ordinary’ shares, with Seme holding 13 and Queen Labotsibeni 12 of the original shares. Both also held 300 ordinary shares, which the queen had since redeemed; she ‘may now be regarded Chief shareholder but who takes little active interest in the paper and is now negotiating with Seme for one or other to take over all shares by both’.258 Changes in capital flow are discussed in the final chapter in this volume.

Abantu-Batho was aimed more at the political African than a broad family readership, yet black family life was circumscribed by segregation and we know little of reading habits.259 We do know that in Europe, press growth spurred the democratisation of reading, making dominant classes anxious, and readers tend to group together as part of a common habitus or ‘informal community of readers’.260 In South Africa, education was less freely accessible. Yet Abantu-Batho contributed to literacy and a reading culture, and the formation of an independent black literary culture. As Sarah Mkhonza argues, Abantu-Batho linked to the birth and growth of the ANC and helped develop political thought.261

What sort of paper was Abantu-Batho? Did it operate bureaucratically or as a collective? If the former, how does one account for diverse views and ‘Native Affairs’ reports emphasising autonomous language sections. If the latter, were chains of command present? Over time, did it become more or less centralised? Was its structure dynamic or static? To what extent were editors part of an elite and how did they relate to ‘the masses’? We offer some answers in the chapters that follow. I suggest that some sort of collective operated, just as lines to Congress ensured a degree of coherence, even rigidity.

Finally, there was limited use of images, not unusual in the press at the time. But as others began to carry more illustrations, Abantu-Batho was held back by a shortage of cash, an ancient press and limited technical knowledge. As Judy Seidman notes, it lacked the ‘in-house capacity to print complex graphic artwork’.262 As South African Worker began to experiment with woodcuts and cartoons to showcase proletarian politics, the lone cartoons in Abantu-Batho were those of advertisers, if from the late 1920s there were splendid photos of women protesters, ICU and ANC heroes, and Marcus Garvey.

These then were the features of the newspaper, its personnel and structure. Clearly, there was not a copy in every home. But Abantu-Batho played a key role in starting to challenge in print the hegemony of a state increasingly moving away from a notional liberalism to a complete denial of black rights. At times of crisis the paper even appears to have been a major explicit mobiliser and organiser of protests. It helped stimulate public debate, and interest in black journalism and literary work, developing an African public sphere and what has come to be known as ‘The New African’.263 The broadsheet was not alone in doing this, and its relationships to individuals and organisations, to political and associational life, other papers, literary and intellectual life, regional and international influences, and classes and gender, along with its themes and tussles, are explored in our chapters, which I now outline.