Читать книгу The People’s Paper - Christopher Lowe - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

For much of the period before the end of the apartheid era the history of the South African press was the history of the white commercial press – the newspapers, magazines, and newsletters that were owned and controlled, produced, and consumed largely on behalf of those who ruled. And yet beneath the surface of this mainstream media lay hundreds of publications that sought to represent the anxieties and fears, interests and needs, hopes and desires of those who had no voice in white South Africa – the Africans, Coloureds and Indians who made up the vast majority of South Africa’s population.

The first publications in African languages – produced by missionaries working in communities of Bantu-speaking Africans in the Northern and Eastern Cape – stem from 1836 or 1837.1 This was only 12 or 13 years after the first newspaper owned by a white colonist was published.2 For most of the period between the late 1830s and the early 1990s, however, the black non-commercial press,3 like the white commercial press, was a sectional press. Black publications were aimed at or intended for separate African, Coloured and Indian communities, just as the European community was the primary consumer of the mainstream white press.

The archive of periodicals representing these subaltern communities – arguably the oldest and largest in sub-Saharan Africa – was virtually unknown before the 1960s/70s, when a few scholars began to interview ordinary Africans who were not necessarily prominent politically, but had been active as church leaders, educators, journalists, literary authors, and businessmen and -women. These scholars were not so much interested in the publications where their African informants had expressed their views, but inevitably this entered into the conversation.

I shall never forget one of my first interviews, which was in 1964 with Gideon Sivetye at his home in Groutville, in the province of what was then called Natal. Sivetye was Chief Albert Luthuli’s pastor, and Luthuli, president-general of the African National Congress (ANC), was then under virtual house arrest within a few hundred metres of where we were meeting. The South African authorities at the time had little interest in anonymous researchers meeting with clergy. As a young scholar who had virtually no training or experience in the art of interviewing, I tried to frame the conversation at the outset. Sivetye, then in his 80s, quickly put me in my place and I was given a rare opportunity to listen to the history of south-eastern Africa as told from an African perspective. Among other things, he mentioned several newspapers that I had never heard of. I made a note of them and in subsequent interviews – especially with people like H. Selby Msimang and R. R. R. Dhlomo – tried to record their memories of the newspapers with which they had been associated.

Thus began my interest in South Africa’s media for the voiceless. My first co-authored publication, The Black Press in South Africa and Lesotho,4 was an attempt to locate, categorise, and describe publications targeted for an African, Coloured and Indian South African audience. Only serial publications – from a daily to an annual – were considered. The archive that was uncovered embraced both non-political and political organs of news and opinion, including general-interest, literary, sport and entertainment publications; teacher and student organs; religious publications; and publications aimed at a wide range of special-interest groups, from agriculture and industry to women and youth. Published 33 years ago, Black Press became a reference text, as it were, for a wide range of research into what might be called South African cultural studies.

I was interested, however, primarily in the political press. Two subsequent volumes – South Africa’s Alternative Press (1997) and South Africa’s Resistance Press (2000)5 – examined selected influential publications from the earliest African political newspapers in the 1880s to the end of the protest-cum-resistance press in the early 1990s.

South Africa’s white-dominated political culture became more and more polarised, especially after the National Party came to power in 1948. A few protest newspapers – the most prominent being The Guardian – made brief appearances as nation-wide publications, but these organs of political opinion had been wiped out by the early 1960s. Neither the Black Consciousness movement in the late 1960s and 1970s, which produced several short-lived publications with a limited readership, nor the resistance movement of the 1980s and early 1990s, which produced a larger number of publications, at least one news agency and in some cases much larger audiences, managed to survive.

Ironically enough, the triumph of South Africa’s liberation movement spelled the end of the non-commercial resistance press. South Africa’s commercial media underwent a transformation in the years after the release of Nelson Mandela from prison in 1990, the first democratic elections in 1994 and the early post-apartheid era under the ANC. Print, radio and television re-emerged as multi-racial instruments of mass communication with dramatic changes in ownership and control structures, and a much broader cross-section of readers, listeners and viewers representing the country’s entire population.

New staff and a changed atmosphere in day-to-day newsroom operations signalled a different set of priorities for the mainstream commercial press. Many of the individuals involved in this transformation were journalists who had worked for resistance publications, but only one of these apartheid-era newspapers – the Mail & Guardian, as it is now called – survived the transition to the post-apartheid era as a viable commercial publication.

The study of the protest-cum-resistance press has matured in recent years as scholars have begun to examine these newspapers and magazines in detail and assess their broader impact on black cultural life. In retrospect, the issues they explored often seem as relevant today as at the beginning of the last century. Political parties and advocacy groups representing the disenfranchised sometimes demonstrated an understanding of the democratic process in their publications that transcended the limitations of ethnicity, geography and the passage of time.

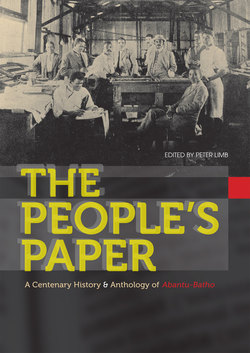

Foremost among these publications was Abantu-Batho, which was launched soon after the founding of the ANC in 1912. While the newspaper may or may not have been the ANC’s official organ, its staff constituted part of the ANC hierarchy and it was always associated with Congress politics in one way or another. Even more importantly, Abantu-Batho provided a fulcrum for discussion and debate within the organisation – shaping and moulding the African nationalist agenda as it shifted over time. Through its vernacular language pages especially – there were isiZulu, isiXhosa and Sesotho/Setswana sections as well as an English section – the newspaper gave voice to the intellectual, social, literary and economic aspirations, as well as the political aspirations, of its emerging urban readership.

Alas, Abantu-Batho led a relatively peripatetic existence until its final demise in 1931. South Africa’s official copyright libraries failed in this instance – as they would fail in many other instances – to keep copies of African nationalist publications on file, and the only issues of the newspaper found and recorded in The Black Press in South Africa and Lesotho were two months in 1920 and about 16 months in 1930–31. Even so, at the time that book was published – at the height of the apartheid era – Abantu-Batho was regarded by a handful of scholars as perhaps the most significant of all African political journals that had existed before the 1930s.

Thus I am thrilled that Peter Limb has brought together an outstanding team of scholars to do justice to Abantu-Batho’s deserved reputation as a paper that not only promoted an ANC political agenda, but also engaged numerous other perspectives (including the political agenda of its royal patrons in Swaziland) in seeking a national audience for its take on issues of the day. As the authors of this volume imply, perhaps even more important were the ways in which Abantu-Batho offered a distinct African response to the dominant Eurocentric linguistic and social narratives of that era.

The authors have managed to uncover numerous stories, letters to the editor and editorials, as well as partial and sometimes whole issues of the newspaper that were hitherto unavailable. I was frankly amazed at the lengths to which they have gone in finding fragments of the newspaper in various parts of the world. Their success is measured by the fact that they have managed to find at least one article from every year that Abantu-Batho was in existence.

This multilayered exploration of the life and times of Abantu-Batho is an outstanding example of what can be accomplished when a project of this kind is studied with imagination and discernment, and with an appreciation for detail that is not always present even in works claiming to be based on primary research. It seems only fitting that the centennial anniversary of the newspaper for ‘The People’, as its title in isiZulu/isiXhosa and Sesotho/Setswana means in English, should be celebrated alongside that of its parent, the African National Congress.

LES SWITZER

Houston, Texas

ENDNOTES

1 The date can be disputed. The London Missionary Society produced a religious tract in Setswana in 1836 entitled Morisa oa Molemo (Shepherd the Good, or The Good Shepherd), but apparently only one issue of this periodical was published and it has not survived. The Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society working among the Xhosa in the Eastern Cape produced Umshumayeli Wendaba (Publisher of the News) in 1837, which is now regarded as the first African periodical.

2 A Cape Colony governor sponsored the first government-owned and -controlled newspaper for white colonists in 1800 (Cape Town Gazette and African Advertiser), while the first privately owned newspaper (South African Commercial Advertiser) appeared in Cape Town in 1824.

3 Newspapers and magazines targeting black or multiracial political and trade union groups, for example, were rarely commercially viable, but some non-political sport and entertainment publications owned by white media chain owners and entrepreneurs, such as Bona, Drum and Post, were very profitable. These publications were addicted to a sex-crime-sport formula and lavish in their photo spreads, cartoons and other types of illustrations – forging a popular black press for a new mass audience that was emerging especially in the cities after World War II.

4 L. Switzer and D. Switzer, The Black Press in South Africa and Lesotho: A Descriptive Bibliographic Guide to African, Coloured and Indian Newspapers, Newsletters and Magazines 1836–1976 (Boston: Hall, 1979).

5 L. Switzer (ed.), South Africa’s Alternative Press: Voices of Protest and Resistance, 1880s–1960s (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997); L. Switzer and M. Adhikari (eds), South Africa’s Resistance Press: Alternative Voices in the Last Generation under Apartheid (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Center for International Studies, 2000).