Читать книгу The People’s Paper - Christopher Lowe - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ENDNOTES

Оглавление1 See V. Khumalo, ‘Ekukhanyeni Letter Writers: A Historical Enquiry into Epistolary Network(s) and Political Imagination in Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa’, in K. Barber (ed.), Africa’s Hidden Histories: Everyday Literacy and Making the Self (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006): 113–42.

2 The Basutoland papers Leselinyana la Lesotho, Mochochonono (The Comet, Maseru, founded 1910) of Abimael Tlale and M. N. Monyakoane, and Naledi ea Lesotho (Star of Basutoland, Mafeteng, 1904) would feed into Abantu-Batho and their columns provide important insights into its history.

3 T. Couzens, ‘The Struggle to Be Independent: A History of the Black Press in South Africa 1836–1960’, History workshop paper, Johannesburg, 6–10 February 1990: 16.

4 R. H. W. Shepherd, Literature for the South African Bantu (Pretoria: Carnegie Corporation, 1936): 6; P. Morris, ‘The Early Black South African Newspaper and the Development of the Novel’, Journal of Commonwealth Literature 15(1), 1980: 16; P. Limb, The ANC’s Early Years: Nation, Class and Place in South Africa before 1940 (Pretoria: Unisa Press, 2010): 19–20, 87.

5 Limb, The ANC’s Early Years: 94, 104.

6 Secretary for Native Affairs (SNA) to Director of Native Labour (DNL), 19 February 1918, in National Archives of South Africa (NASA), Pretoria, DNL, Government Native Labour Bureau (GNLB), vol. 90, 144/13 D205 (hereafter only the DNL reference is given), asking clerks in his office to read Abantu-Batho regularly for the benefit of the chief censor.

7 Banning was more pronounced in India: Lord Curzon stated the Indian press had shown ‘a most exemplary and gratifying loyalty’ in the South African War, but ‘now and then one detects a note of veiled irony’ (letter 28 December 1902, in Private Correspondence India, Curzon to Hamilton, vol. X, India Office, British Library, D510/3; M. Israel, Communications and Power: Propaganda and the Press in the Indian Nationalist Struggle, 1920–47 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994); C. Paul, Reporting the Raj: The British Press and India, c.1880–1922 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003): 23.

8 South Africa, Report of the South African Native Affairs Commission 1903–1905 (London: HMSO, 1905): 65.

9 Again the Indian comparison is apposite; see C. A. Bayly, Empire and Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India, 1780–1870 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000): 2.

10 A. Odendaal, Vukani Bantu! Black Protest Politics in South Africa to 1912 (Cape Town: David Philip, 1984): 260.

11 J. Starfield, ‘Dr S. Modiri Molema (1891–1965): The Making of an Historian’, PhD, University of the Witwatersrand, 2007: 240 n. 69.

12 A point made by A. Davidson, I. Filatova, V. Gorodnov and S. Johns (eds), South Africa and the Communist International: A Documentary History, vol. 2 (London: Cass, 2003): 4 n. 3.

13 R. Whitaker, ‘History, Myth and Social Function in Southern African Nguni Praise Poetry’, in D. Konstan and K. Raaflaub (eds), Epic and History (Oxford: Blackwell, 2010): 381.

14 I owe the latter comment to Chris Lowe’s ever-sharp insight.

15 Lack of data renders its history subject to possibilities, on which see G. Hawthorn, Plausible Worlds: Possibility and Understanding in History and the Social Sciences (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

16 The reference to Allan Kirkland Soga seems wrong, as there is no evidence of his involvement, although he was active in the first years of the SANNC and involved in the contemporary short-lived Native Advocate.

17 S. M. Molema, The Bantu Past and Present: An Ethnographical and Historical Study of the Native Races of South Africa (Edinburgh: Green, 1920): 306, 304.

18 C. Dawbarn, My South African Year (London: Mills & Boon, 1921): 108. This is a quote from ‘Parting of the Ways: Part II’, Abantu-Batho, February–March 1920; see Part II of this volume.

19 E. W. Smith, ‘Some Periodical Literature Concerning Africa’, International Review of Missions 15, 1926: 605–6.

20 E. Roux and W. Roux, Rebel Pity: The Life of Eddie Roux (London: Penguin, 1972): 35.

21 E. Roux, ‘The Bantu Press’, Trek, 24 August 1945: 12. Here he also gives ‘about 1935’ for its demise, an erroneous date reproduced by later writers.

22 E. Roux, Time Longer than Rope: A History of the Black Man’s Struggle for Freedom in South Africa (London: Gollancz, 1948): 119–20, 358. For one such intervention, see S. H. Malunga, ‘Abantsundu base Africa Bati, Mayibuye i Africa’, Abantu-Batho, 2 December 1920.

23 In this book (p. 125) he cites an Abantu-Batho article on women’s anti-pass law struggles; see Part II.

24 E. Rosenthal, Bantu Journalism in South Africa (Johannesburg: Society of Friends of Africa, 1949): 13–14.

25 P. la Hausse de Lalouvière, ‘The War of the Books: Petros Lamula and the Cultural History of African Nationalism in 20th-century Natal’, in D. Peterson and G. Macola (eds), Recasting the Past: History Writing and Political Work in Modern Africa (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2009): 52.

26 See Part II. We have not had the good fortune to chance upon a cache of lost issues as did David Ambrose, Naledi ea Lesotho (Roma: House 9 Publications, 2007). This independent paper, founded in 1904, reported the ANC founding and carried a 1915 article from Abantu-Batho, with Simon Phamotse a link, but after 1921, when it published pro-Garvey pieces, it faced censure and became increasingly moderate.

27 See M. Work (ed.), Negro Year Book 1916–7 (Tuskegee: Negro Year Book Company, 1917).

28 F. Wilson and D. Perrot (eds), Outlook on a Century: South Africa 1870–1970 (Lovedale: Lovedale Press, 1972); R. A. Hill (ed.), The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers, vols. 9 and 10 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995 and 2006); T. Karis and G. M. Carter (eds), From Protest to Challenge: A Documentary History of African Politics in South Africa, 1882–1964, vol. 1 (Stanford: Hoover University Press, 1972). A facsimile of the 19 October 1927 issue appears in A. Davidson, IUzhnaia Afrika: Stanovlenie sil protesta 1870–1924 (Moscow: Nauka, 1972).

29 Roux, Time Longer than Rope: 358.

30 L. Switzer and D. Switzer, The Black Press in South Africa and Lesotho: A Descriptive Bibliographic Guide to African, Coloured and Indian Newspapers, Newsletters and Magazines 1836–1976 (Boston: Hall, 1979): 24–26; L. Switzer, ‘Moderation and Militancy in African Nationalist Newspapers during the 1920s’, in K. Tomaselli and P. E. Louw (eds), The Alternative Press in South Africa (Bellville: Anthropos, 1991): 41.

31 T. Couzens, ‘Robert Grendon: Irish Traders, Cricket Scores and Paul Kruger’s Dreams’, English in Africa 15(2), 1988: 78. He is incorrect to state it was founded in 1913 (T. Couzens, The New African: A Study of the Life and Work of H. I. E. Dhlomo (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1985): xv; A. Bingham, Gender, Modernity, and the Popular Press in Inter-war Britain (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2004): 1.

32 D. Coplan, In Township Tonight! South Africa’s Black City Music and Theatre (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008) and B. Peterson, Monarchs, Missionaries, and African Intellectuals (Trenton: Africa World Press, 2000): 16–17 appreciate the shaping of black ‘thinking and cultural practices’ by liberals, but do not use Abantu-Batho and miss the beating heart at the core of Johannesburg associations.

33 L. Switzer (ed.), South Africa’s Alternative Press: Voices of Protest and Resistance, 1880s–1960s (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997); L. Switzer and M. Adhikari (eds), South Africa’s Resistance Press: Alternative Voices in the Last Generation under Apartheid (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Center for International Studies, 2000); I. Ukpanah, The Long Road to Freedom: Inkundla ya Bantu (Bantu Forum) and the African Nationalist Movement in South Africa, 1938–1951 (Trenton: Africa World Press, 2005).

34 Switzer and Switzer, The Black Press: 25.

35 Ibid.

36 C. Lowe, ‘Swaziland’s Colonial Politics: The Decline of Progressivist South African Nationalism and the Emergence of Swazi Political Traditionalism, 1910–1939’, PhD, Yale University, 1998. Like Lowe, Switzer (‘Moderation and Militancy’: 41) argues that ‘African nationalists never had a truly national newspaper’.

37 ‘Abantu-Batho became the official organ of [ANC] .... This gave the new organ a fillip that sent it soaring all over South Africa’ (T. D. M. Skota, The African Who’s Who: An Illustrated Classified Register and National Biographical Dictionary of the Africans in the Transvaal (Johannesburg: CNA, 1966): 80.

38 African World (Cape Town) 1(5), 27 June 1925, cover.

39 Government Printer to SNA, 30 April 1920, DNL 144/13 D205.

40 A. J. Friedgut, ‘The Non-European Press’, in E. Hellman (ed.), Handbook on Race Relations in South Africa (Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 1949): 491.

41 G. Carter, The Politics of Inequality: South Africa since 1948 (New York: Praeger, 1959):43.

42 M. Benson, The African Patriots: The Story of the African National Congress of South Africa (London: Faber & Faber, 1963): 31; cf. Skota interview notes, Benson Papers, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, Mss. 348942/1.

43 A. Odendaal, Vukani Bantu!: 286.

44 P. Walshe, The Rise of African Nationalism in South Africa: The African National Congress, 1912–1952 (London: Hurst, 1970): 60; P. Bonner, ‘The Transvaal Native Congress, 1917–20: The Radicalisation of the Black Petty Bourgeoisie on the Rand’, in S. Marks and R. Rathbone (eds), Industrialisation and Social Change in South Africa: African Class Formation, Culture and Consciousness 1870–1930 (London: Longman, 1982): 272.

45 A. Cobley, Class and Consciousness: The Black Petty Bourgeoisie in South Africa, 1924 to 1950 (New York: Greenwood Press, 1990): 152, 154–55; Walshe, The Rise of African Nationalism: 216–17.

46 S. Dubow, The African National Congress (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 2000) and H. Holland, The Struggle: A History of the African National Congress (London: Grafton, 1989) refer to other papers, but not Abantu-Batho. P. Maylam, A History of the African People of South Africa (Cape Town: David Philip, 1986): 155 is one of few general histories to mention it and notes that its publication also in English sought to develop broad solidarity. R. Ross, A. Mager and B. Nasson (eds), The Cambridge History of South Africa, vol. 2 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011) fails even to mention it.

47 G. Mbeki, Learning from Robben Island: The Prison Writings of Govan Mbeki, ed. C. Bundy (Cape Town: David Philip, 1991): 89.

48 L. Forman, A Trumpet from the Housetops: The Selected Writings of Lionel Forman, ed. S. Forman and A. Odendaal (Cape Town: Mayibuye Centre and David Philip, 1992): xxvi, 55–58.

49 B. Bunting, Who Runs Our Newspapers? (Cape Town: New Age, 1960): 6.

50 Mayibuye 2, 1969; Sechaba, 1988: 8. Mayibuye recalled the arrest of its director in 1918 (Veteran, ‘Gold Miners’ Wages’, Mayibuye 2(22), 1968: 3; cf. African Communist 1974: 46; 1975: 83.

51 J. Simons and R. Simons, Class and Colour in South Africa, 1850–1950 (London: IDAF, 1985): 136.

52 F. Meli, South Africa Belongs to Us: A History of the ANC (Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House, 1988): 210.

53 J. Zug, The Guardian: The History of South Africa’s Extraordinary Anti-apartheid Newspaper (Pretoria: Unisa Press; East Lansing: MSU Press, 2007): 159.

54 Karis and Carter, From Protest to Challenge, vol. 2: 87.

55 A. B. Xuma to C. P. Molefe, Vereeniging, 7 May 1948, University of the Witwatersrand Historical Papers (hereafter Wits Historical Papers), A. B. Xuma Papers, ABX 480507b. In the 1940s Mbeki corresponded with Xuma on the need for an ANC press; see A. B. Xuma, Autobiography and Selected Works, ed. P. Limb (Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society, 2012).

56 ‘Towards a Congress newspaper’, Congress Voice Bulletin [between November 1955 and March 1956] in ‘ANC source material’, Records relating to the Treason Trial, Regina vs. F. Adams and 152 others on a Charge of High Treason, Wits Historical Papers, AD1812, Ea1.14.1.4. I thank Paul Landau for this item.

57 Sekgokgo wa gaTshesane, ‘The ANC Philosopher: On the Party’s Lack of Development’, 26 October 2010, <http://www.sekgokgo.blogspot.com> (accessed 1 November 2011).

58 S. Johnson, ‘An Historical Overview of the Black Press’, in K. Tomaselli and P. E. Louw (eds), The Alternative Press in South Africa (Bellville: Anthropos), 1991: 19, 21; Switzer, ‘Moderation and Militancy’: 39.

59 Zug, The Guardian; Ukpanah, The Long Road; Switzer, ‘Moderation and Militancy’; Switzer and Adhikari, South Africa’s Resistance Press; J. Opland (ed. and trans.), The Nation’s Bounty: The Xhosa Poetry of Nontsizi Mgqwetho (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2007).

60 S. T. Plaatje, The Boer War Diary of Sol T. Plaatje, ed. J. Comaroff (Johannesburg: Macmillan, 1973); B. Willan, Sol Plaatje: South African Nationalist, 1876–1932 (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1982); H. Hughes, The First President: A Life of John L. Dube, Founding President of the ANC (Auckland Park: Jacana, 2011); D. D. T. Jabavu, The Life of John Tengo Jabavu: Editor of Imvo Zabantsundu, 1884–1921 (Lovedale: Lovedale Press, 1922).

61 A. W. G. Champion, The Views of Mahlathi: Writings of A. W. G. Champion, a Black South African, ed. M. W. Swanson (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1983): 57.

62 R. V. S. Thema, ‘Out of Darkness: From Cattle Herding to the Editor’s Chair’, SOAS, Mss. 320895, (variant copy also in Wits Historical Papers); R. van Diemel, ‘In Search of Freedom, Fair Play and Justice’: Josiah Tshangana Gumede 1867–1947: A Biography (Cape Town: self-published, 2001).

63 C. Lowe, ‘Abantu-Batho and the South African Native National Congress in the 1910s’, paper presented to the Canadian Research Consortium on Southern Africa, May 1998; C. Lowe, ‘The Tragedy of Malunge, or, the Fall of the House of Chiefs: Abantu-Batho, the Swazi Royalty, and Nationalist Politics in Southern Africa, 1894–1927’, paper presented to the African Studies Association meeting, Boston, December 1993; C. Lowe, ‘Swaziland’s Colonial Politics.

64 Limb, The ANC’s Early Years; P. Limb, ‘“Representing the Labouring Classes”: African Workers in the African Nationalist Press 1900–60’, in L. Switzer and M. Adhikari (eds), South Africa’s Resistance Press: Alternative Voices in the Last Generation under Apartheid (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Center for International Studies, 2000).

65 G. Christison, ‘African Jerusalem: The Vision of Robert Grendon’, PhD, University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2007; C. Woeber, ‘The Mission Presses and the Rise of Black Journalism’, in D. Attwell and D. Attridge (eds), Cambridge History of South African Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012): 204–25. Christison’s chapter deals with his role as editor, and those interested in his life and philosophy should read Christison, ‘African Jerusalem’.

66 South Africa, Official Year Book of the Union (Pretoria: Government Printer, 1917): 278 (this number grew to five by 1915); T. Cutten, A History of the Press in South Africa (Cape Town: National Union of South African Students, 1935): 81.

67 See, for instance, The Rand Daily Mail for the period October–December 1912.

68 C. Saunders, ‘Pixley Seme: Towards a Biography’, South African Historical Journal 25, 1991: 208, citing Seme to Locke 24 January 1912, Howard University, Locke Papers, 164-84/36, 38; H. S. Selby, H. Selby Msimang Looks Back (Johannesburg: SA Institute of Race Relations, 1971): 5. In 1914 Seme pithily wrote to Locke: ‘Please write to our Native Paper’ (Howard University, Locke Papers, 164-84/38); also cited in L. Harris and C. Molesworth, Alain L. Locke: Biography of a Philosopher (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008): 386. This file appears to be lost and I am grateful to Robert Edgar for making his transcript available.

69 Skota told Couzens (Couzens, ‘Robert Grendon’: 77) that Seme recruited Grendon ‘to edit the first edition’, but Skota is sometimes wrong and there is evidence especially in Ilanga lase Natal (hereafter Ilanga) that Kunene was the inaugural editor.

70 ‘Abantu’, Ilanga, 13 September 1912.

71 Umbuzeli Wohlanga of East London, about which little is known, although it was mentioned by Leselinyana, 23 May 1912, drawing from Mochochonono.

72 ‘Amanqaku: Amapepa Abantu’ (Bits and Pieces: People’s Newspapers), Imvo Zabantsundu (hereafter Imvo), 1 October 1912. My thanks to Jeff Opland for the translation. It is odd that Jabavu, hostile to Congress, gave his blessing to Seme’s paper.

73 In October Kunene visited the Ilanga office near Durban to show a mock-up of Abantu-Batho, ‘which is to be issued in November’ (‘Izindatyana NgeZinto naBantu?’, Ilanga, 25 October 1912: ‘umhleli wepepa elisha elizopuma eGoli ngo Nov. esesike saboniswa isampula lalo’); see also ‘Ezixoxa ngabantu’, Izwe la Kiti, 30 October 1912. My thanks to Grant Christison for these sources.

74 Abantu-Batho, 25 December 1912: 1, 8, 15, 22; 29 January 1913, Swaziland National Archives (SwNA), Resident Commissioner Secretariat (RCS) 124/13; see Part II. Based on two in October, eight in November–December.

75 Brief notice in Ilanga, 25 October 1912 and ‘Ezixoxa ngabantu’, Izwe la Kiti, 30 October 1912, both announcing Cleopas Kunene as editor. See also ‘Izindatyana NgeZinto naBantu’, Ilanga, 1 November 1912 on collaboration between the papers of Mangena and Seme.

76 Leselinyana, 24 October 1912, trans. Peter Lekgoathi. Mochochonono and Naledi covered the first Congress (‘Phutheho ea Batala Bloemfontein’, Leselinyana, 25 Pherekhong (January) 1912).

77 ‘Izindatyana NgeZinto naBantu’, Ilanga, 25 October 1912 (trans. commissioned by Grant Christison); Izwe la Kiti, 30 October 1912 (also noted in ‘Izindatyana NgeZinto naBantu’, Ilanga, 8 November 1912).

78 ‘Ezase Pitoli’ ‘Pretoria News’, Ilanga, 6 December 1912.

79 N. Mokhonoana and M. Strassner, Zincwadi eziqoqiwe ngolwazi lolimi lwesiZulu ngonyaka ka 1998/Bibliography of the Zulu Language to the Year 1998 (Pretoria: National Library, 1999): 1.

80 Sol Plaatje to Silas Molema, 8, 14 August 1912, Wits Historical Papers, Molema-Plaatje Papers, Da19–20; Willan, Sol Plaatje: 158. Plaatje was able in September to relaunch Tsala ea Becoana as Tsala ea Batho, incorporating Motsualle ba Babatsho, which is not to be confused with Motsoalle.

81 ‘Iso Lase Swazini’, Ilanga, 8 November 1912; Christison, ‘African Jerusalem’: 782.

82 ‘Transvaal Notes’, Indian Opinion, 19 October 1912. Given this time frame, the Swazi printing press initially may not have been used to print Abantu-Batho; see Chris Lowe’s chapter in this volume.

83 ‘Ezase Pitoli’, Ilanga, 11 October 1912: ‘Kukona ilima elikulu laba Mmeli, oMessrs Mangena no Seme lokwenza ipepa lezindaba “Newspaper” elizobizwa ngokutiwa “Native Advocate”’.

84 ‘Ezase Pitoli’, Ilanga, 6 December 1912; T. D. M. Skota (ed.), The African Yearly Register, Being an Illustrated National Biographical Dictionary (Who’s Who) of Black Folks in Africa, 2nd ed. (Johannesburg: Esson, [1932]): 43; Walshe, The Rise of African Nationalism: 32; Switzer, The Black Press: 28; L. Switzer, ‘Introduction’, in L. Switzer (ed.), South Africa’s Alternative Press: 30; Rosenthal, Bantu Journalism: 13; ‘Moemedi oa Batho’ (‘South African Native Advocate)’, Tsala ea Batho, 24 May 1913; ‘Izindatyana NgeZinto naBantu’, Ilanga, 1 November 1912.

85 I thank Sifiso Ndlovu for the latter idea (e-mail to the author, 25 July 2011).

86 S. Msimang, ‘History of Black Politics in South Africa’: 3, paper presented to a NUSAS seminar, April 1972 (copy in Digital Innovation South Africa, <http://www.disa.ukzn.ac.za>). My thanks to Paul Landau for this.

87 Skota, The African Who’s Who: 65, who imperfectly recalls the merger as occurring in 1913: Chris Lowe (e-mail, 21 August 2011) suggests he may have conflated Dunjwa’s earlier move to Abantu-Bantu in 1913 with the merger. An early mention of this paper is in ‘Awomhlei Amazwi’, Ilanga, 12 May 1911.

88 R. T. Kawa, ‘Oziroxisileyo’, Imvo, 8 October 1912.

89 Ramosime of the Transvaal Native Organisation is listed as Molomo oa Batho editor (‘List of Native Newspapers in circulation throughout the Union …’ and ‘List of Native Newspapers printed in the Transvaal Province’ (1911), NASA, Pretoria, SNA 494 826/11; I thank Chris Lowe for this). Ramosine was a Johannesburg delegate to the SANNC executive in 1914 (‘SA Native National Congress’, Tsala, 15 August 1914).

90 ‘Abantu Batho’, c. February 1916, DNL 1329/14 D48. A Native Affairs note of 1911 also reveals the editorial details. Saul Msane was based at 10 Kruis Street in 1914 (Saul Msane, ‘The Natives’ Land Act 1913’, Ilanga, 30 January 1914).

91 Ilanga, 1 September 1916; Christison, ‘African Jerusalem’: 791. The Government Printer confirmed that in ‘September last the Native newspaper “Molomo-oa-Batho” was incorporated in the “Abantu-Batho”’ and that since the latter had guaranteed that ‘[g]overnment announcements would appear in the amalgamated paper in the three Bantu languages … the monthly allowance (£8.6.8) made to the former was discontinued, the amount paid to the latter was doubled’ (F. Knightly, Government Printer to SNA, 29 March 1917, ‘Advertising in Native Newspapers’, DNL 144/13, A.3/64/1206). Advertising rates were modest: in 1930 a single column per inch per insertion cost four shillings (notice in Abantu-Batho, 27 November 1930). On advertising, see chapter 11 in this volume.

92 ‘Yinina Le!’, Umlomo wa Bantu, c. January 1914, repr. in Tsala ea Batho, 14 January 1914.

93 See the fine cameos on components of this politics in Odendaal, Vukani Bantu! up to 1912; Bonner, ‘The Transvaal Native Congress’ on 1918–20; and P. la Hausse de Lalouvière, ‘“Death Is Not the End”: Zulu Cosmopolitanism and the Politics of Zulu Cultural Revival’, in B. Carton, J. Laband and J. Sithole (eds), Zulu Identities: Being Zulu, Past and Present (Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press Press, 2008): 256–72 on how Rand ‘cosmopolitanism life’ helped Zulu intellectuals combine ethnic patriotism with racial nationalism into an ideological weapon.

94 H. Jones, A Biographical Register of Swaziland to 1902 (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1993): 400–2. She encouraged Malunge and Sobhuza to align with the ANC (P. LaNdwandwe, ‘Akusiko Kwami, Kwebantfu’: Unearthing King Sobhuza II’s Philosophy (Eshowe: Umgangatho, 2009): 50).

95 M. Genge, ‘Power and Gender in Southern African History: Power Relations in the Era of Queen Labotsibeni Gwamile Mdluli of Swaziland, ca. 1875–1921’, PhD, Michigan State University, 1999: 407.

96 O. O’Neil, Adventures in Swaziland: The Story of a South African Boer (New York: Century, 1921): 364.

97 C. C. Watts, Dawn in Swaziland (Westminster: Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, 1922): 40–41.

98 H. Filmer and P. Jameson, Usutu! A Story about the Early Days of Swaziland (Johannesburg: CNA, 1960): 9, 55.

99 A. Kanduza, ‘Intellectuals in Swazi Politics’, in S. Dupont-Mkhonza, J. Vilakati and L. Mundia (eds), Democracy, Transformation, Conflict and Public Policy in Swaziland (Kwaluseni: OSSREA, 2003): 57.

100 H. Macmillan, ‘A Nation Divided? The Swazi in Swaziland and the Transvaal, 1865–1986’, in L. Vail (ed.), The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa (London: James Currey, 1989): 295, citing Mabaso, manager, Abantu-Batho Ltd. to Financial Secretary, Swaziland, 15 August 1927, and the liquidator, Abantu-Batho Ltd. to Resident Commissioner, Swaziland, 24 January 1929, SwNA, RCS 51/26.

101 ‘Ezase Goli’, Ilanga, 30 April 1915.

102 Abantu-Batho 11, 20 March 1914, in D. H. Gillis, The Kingdom of Swaziland: Studies in Political History (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1999): 160–66; reproduced in J. S. Crush, The Struggle for Swazi Labour, 1890–1920 (Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1987): 224–25 and in National Archives of the United Kingdom, Colonial Office (CO) 417/546.

103 La Hausse de Lalouvière, ‘Death Is Not the End’.

104 B. Anderson, H. Barker and S. Burrows, ‘Introduction’, in H. Barker and S. Burrows (eds), Press, Politics and the Public Sphere in Europe and North America, 1760–1820 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002): 1, 17.

105 J. Aitchison, The Word Weavers: Newshounds and Wordsmiths (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007): xi.

106 Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (London: James Currey, 1986); L. Hardwick, ‘Playing around Cultural Faultiness: The Impact of Modern Translations for the Stage on Perceptions of Ancient Greek Drama’, in A. Chantler and C. Dente (eds), Translation Practices: Through Language to Culture (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2009): 167, 183.

107 Brian Willan has pushed back the date of such engagements to the 1870s in ‘Whose Shakespeare? Early African Engagement with Shakespeare in South Africa’, paper presented to the Fourth European Conference of African Studies, Uppsala, June 2011.

108 ‘S.A. Native Congress’, Tsala ea Batho, 17 February 1912; Odendaal, Vukani Bantu!: 274.

109 J. M. T., ‘Inxube Vange’, Ilanga, 6 December 1912; C. Lowe, e-mail, 19 May 2011 suggests English, isiZulu and Sesotho capacity was there with Letanka, Seme and Kunene, while isiXhosa may have come in part via Seme’s isiXhosa-speaking first wife.

110 P. St-Pierre, ‘Translating (into) the Language of the Coloniser’, in S. Simon and P. St-Pierre (eds), Changing the Terms: Translating in the Postcolonial Era (Ottawa: University of Ottawa, 2000): 275.

111 See, for example, N. Dhlomo, ‘The Theory, Value and Practice of Translation with Reference to John L. Dube’s Texts Isita Somuntu nguye uqobo lwakhe (1928) and Ukuziphatha kahle (1935)’, MA, University of Durban-Westville, 1996, chap. 2.

112 E. Morrison, ‘Reading Victoria’s Newspapers 1838–1901’, in D. Walker et al. (eds), Books, Readers, Reading (Geelong: Deakin University, 1992): 129.

113 K. Tomaselli, R. Tomaselli and J. Muller, ‘The Construction of News in the South African Media’, in K. Tomaselli and J. Muller (eds), The Press in South Africa (Bellville: Anthropos, 1989): 22–23.

114 See A. Curthoys, ‘Histories of Journalism’, in A. Curthoys and J. Schultz (eds), Journalism: Print, Politics and Popular Culture (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1999): 1–9.

115 B. Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983, 1991), 13–15, 137.

116 L. Sage, ‘Foreword’, in K. Campbell (ed.), Journalism, Literature and Modernity: From Hazlitt to Modernism (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004): x.

117 To give one example, the first two issues of Ilanga were replete with mentions of ‘the people’ and even ‘the masses’ (W. C. Wilcox, ‘Correspondence to the Editor’, Ilanga 1, 10 April 1903; H. A., ‘Education of Body and Mind’, Ilanga 2, 17 April 1903).

118 ‘South African Native National Congress’, Tsala ea Batho, 10 May 1913, lists Naledi ea Batho, Molomo oa Batho, Abantu-batho, Tsala ea Batho and APO as ‘newspaper press organs’.

119 See Limb, The ANC’s Early Years: 9–15, and the authors discussed therein.

120 J. Nerone, ‘Genres of Journalism History’, in C. Robertson (ed.), Media History and the Archive (New York: Routledge, 2011): 26–27: in the United States early African American and radical papers, for example, were able to draw attention to themselves by this recirculation. Here I pay tribute to the World Newspaper Archive of the Center for Research Libraries/Readex, which has placed many such papers online.

121 L. Thompson, A History of South Africa, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996): 325, noting it was the editors of black papers who provided leadership to decide a strategy against discrimination.

122 Transvaal Native Congress Constitution, [c.1919], 9, copy in NASA, Pretoria, Secretary for Native Affairs (NTS) 7204 17/326, attached to 1217/14/110, S. M. Pritchard, DNL to SNA, 17 May 1919. It is not clear if this is the first version of the constitution, which was being discussed by 1915 (‘Transvaal Native Council’, Ilanga, 11 June 1915).

123 Opland, The Nation’s Bounty.

124 ‘Presidential Address to the National Congress at Bethlehem’, Abantu-Batho, 25 April, 9 May 1918.

125 Hughes, The First President: 195. The conflict cannot be ascribed purely to personal differences, but neither does it appear rooted in any deep gulf of political philosophy, as both were moderately inclined.

126 See Part II: Abantu-Batho, 4 July 1918, DNL 1441/D205.

127 B. Sundkler, Bantu Prophets in South Africa (London: Lutterworth, 1948): 35.

128 ‘ANC Secretary General’s Report’ [1930], in Karis and Carter, From Protest to Challenge, vol. 1: 306–8.

129 ‘Native Papers & Missionaries’, Tsala, 21 March 1914. Abantu-Batho sprang to his defence when attacked in Volkstem (‘I “Volkstem” No Mr. S. T. Plaatje’, Ilanga, 2 April 1915, repr. from Abantu-Batho).

130 Futa, ‘Imvo vs. the Natives and Their “Would-Be Leaders”’, Tsala, 29 November 1913: a reference to Jabavu’s claim that the Land Act had been accept by the people en masse via their Councils of Chiefs.

131 Skota, The African Yearly Register.

132 C. S. Mabaso to DNL, 16 February 1914, DNL 1329/14 D48, ‘Anglo German War: Native Newspapers: Abantu Batho’.

133 Benson, The African Patriots: 38.

134 Acting DNL to SNA, 16 February 1916, DNL 1329/14 D48.

135 As one of the delegates to Britain, he was introduced as ‘Managing Director, Abantu-Batho, Ltd’, probably assuming this role from Seme around 1916; see ‘Summary of Statements made to the African Telegraph by the South African Delegation …’, African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror, May–June 1919: 226.

136 Skota, The African Who’s Who: 53 has Selope Thema only as a ‘correspondent’.

137 Grendon to Ilanga, 19 November 1915, citing Msimang in Abantu-Batho, 5 December 1913, with this title.

138 R. V. Selope Thema, ‘How Congress Began’, in M. Mutloatse (ed.), Reconstruction: 90 Years of Black Historical Literature (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1981): 108–14; originally published in Drum, 25 July 1953: 41.

139 C. de. B. Webb and J. Wright (eds), The James Stuart Archive of Recorded Oral Evidence Relating to the History of the Zulu and Neighbouring Peoples, vol. 5 (Scottsville: University of Natal Press, 2001): 269.

140 ‘The War News’, Abantu-Batho, 6 January 1916; see Part II. Crush, The Struggle for Swazi Labour: 161 refers to Seme publishing articles in 1913 on Swaziland, but these most likely would have been by Kunene.

141 DNL to editor, Abantu-Batho, 7 December 1914, DNL 1329/14 D48, ‘Anglo German War: Native Newspapers: Abantu Batho’.

142 Memorandum of Acting DNL to SNA reporting interview of Seme on 23 March 1916, DNL 1329/14 D48. An undated draft telegram by M. Carroll in the same file asserts Seme’s probable authorship in the interval between Kunene’s departure and Msane’s appointment as editor (Acting DNL to SNA, 24 March 1916, DNL 1329/14 D48).

143 ‘Sale in Execution’, Rand Daily Mail, 24 March 1916.

144 Abantu-Batho interviewed Seme in 1923 on his return from overseas on behalf of the Swazi monarchy, but recent research, if not conclusive, suggests he may also have joined his friend Locke to tour Egypt and apparently witness the opening of the tomb of King Tutankamen (Harris and Molesworth, Alain L. Locke: 79, 145 citing Locke, ‘Impressions of Luxor’, Howard Alumnus, vol. 2 May 1924. Cf. Chris Saunders’ chapter in this volume).

145 See ‘U Cleopas Kunene Kaseko!’, Ilanga, 20 April 1917: he died on 15 April of bowel flu, contracted in Swaziland where had been undertaking Abantu-Batho business. Thanks to Grant Christison for this.

146 Roux, Time Longer than Rope: 111. Letterhead, Cleopas Kunene to DNL, 16 July 1914, DNL 362/14 D80.

147 Webb and Wright, The James Stuart Archive, vol. 1: 273–74.

148 Tsala, 24 July 1915 suggested he would make a fine ‘Prisoners’ Vigilant’ on the SANNC executive.

149 ‘Ugqainyanga’, Ilanga, 18 February 1916; Acting DNL to SNA, 16 February 1916, in DNL 1329/14 D48, by which time ‘there was no Zulu editor as Cleopas Kunene had severed his connection’.

150 Christison, ‘African Jerusalem’: 778, citing ‘Sale in Execution’, Rand Daily Mail, 24 March 1916.

151 ‘Ezase Jozi’, Ilanga 14, 28 July 1916 and Christison, ‘African Jerusalem’: 790 ff., who points to intense rivalries between Kunene and Grendon over the editorship and other matters.

152 Josiah Mapumulo, ‘The Late Mr C. Kunene: An Appreciation’, Ilanga, 4 May 1917; ‘An Ex-Teacher’, ‘The Late Mr C. Kunene’s Successor’, Ilanga, 15 June 1917 also remarked on his role as chairperson of the Natal Teachers’ Conference at the same time as being editor of Abantu-Batho.

153 ‘South African Native National Congress’, Ilanga, 8 June 1917.

154 Selby Msimang, Hon. Sec. SANNC to Secretary, Aborigines Protection Society (APS), 13 October 1913, Rhodes House Library, Oxford University, in the Papers of the Anti-Slavery Society and APS Papers, Mss. Brit. Empire s.22 G203; Selope Thema to John Harris, London, 1 June 1921, Rhodes House Library, APS Papers, Mss. Brit. Empire s.23 H2/50.

155 ‘Call to the Native Workers’, International, 7 April 1916.

156 Skota, The African Yearly Register: 171. He lived in what became Letanka Street, Western Native Township; ‘Prospectus ISO Limited’, Abantu-Batho, 5 June 1930 listed him as: ‘profession journalist’.

157 Acting DNL Cooke to SNA, 28 February 1918, DNL 144/13 D205: ‘I regret to tell you that in my opinion the whole tone of this paper has considerably changed for the worse. One of the chief influences of a retrogressive nature is that of Mvabasa [Mvabaza] who is a bitter and intelligent fellow and who I understand is mixed up to some extent with Bunting and his associates.’

158 Dower to Cooke, 12 February 1918, DNL 144/13 D205(1); Abantu-Batho, 17 January 1918. Letanka was editor, but it is not clear if he was the author, and Dower did ‘not want it to appear that any threat or withdrawal of Government patronage is held over him on account of this article’.

159 J. Pilger, ‘Introduction’, in J. Pilger (ed.), Tell Me No Lies: Investigative Journalism and Its Triumphs (London: Jonathan Cape, 2004): xv.

160 Skota, The African Who’s Who: 65. Rosenthal (Bantu Journalism: 13) dubs him an itinerant musical instrument seller.

161 DNL to SNA, 1913, DNL 2528, approving his application for exemption from the pass laws.

162 Skota, The African Who’s Who: 65.

163 ‘The Future of the German Colonies’, Abantu-Batho, 7 February 1918, cited in A. Grundlingh, Fighting Their Own War: South African Blacks and the First World War (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1987): 133–34.

164 Letter of Letanka and H. Msane with resolution, 11 December 1916 on letterhead with office-bearers, Thema to SNA, 20 May 1918, Thema to SNA, 13 June 1918, all in NTS 7204 17/326; TNC, Constitution (1919), para. 19, 9, NTS 7204 17/326.

165 Cooke to SNA, 28 February 1918, DNL 144/13 D205. He spoke Sepedi. Skota, The African Who’s Who: 53 remembers him only as a ‘correspondent’ of the paper, but was himself then rather distant in Kimberley.

166 R. V. Selope Thema, ‘Out of Darkness: From Cattle Herding to the Editor’s Chair’, SOAS, Mss. 320895: 47, 51. Thema’s preface is dated 1935, but the text is ‘completed’ by another hand c.1950.

167 ‘Mr Thema: His Life and His Achievements’, Bantu World, 24 September 1955.

168 E. J. Verwey, New Dictionary of South African Biography, vol. 1 (Pretoria: HSRC, 1995): 245. In London he also published S. Thema, ‘Slavery within the British Empire’, African Telegraph, December 1919.

169 Thema, ‘Out of Darkness’: 68–73, 60. In 1928 he noted a small group of ‘editors and proprietors of weekly newspapers whose columns are devoted to the furtherance of the cause of their race’ (R. V. S. Thema and J. D. R. Jones, ‘In South Africa’, in M. Stauffer (ed.), Thinking with Africa: Chapters by a Group of Nationals Interpreting the Christian Movement (London: Student Christian Movement, 1928): vi, 60–1, 63.

170 T. R. H. Davenport and K. S. Hunt, The Right to the Land (Cape Town: David Philip, 1975): 71.

171 Rhodes House Library, APS Papers, Mss. Brit. Empire s.23 H2/50 has the letter: Thema to Harris, 1 June 1921.

172 Benson, The African Patriots: 38, but letterheads do not reflect this: Mabaso to DNL, 14 February 1914, DNL to SNA, 16 February 1916, DNL 1329/14 D48, the latter noting that on 6 January there was ‘no Zulu Editor’ as Kunene had ‘severed his connection with the paper and Saul Msane had not yet joined it’.

173 Skota, The African Who’s Who: 104; ‘Petition’, Ilanga, 15 May 1914; Walshe, The Rise of African Nationalism: 217.

174 Police report of meeting, 29 June 1918, NTS, file 281, GNLB 281 446/17 D48, ‘Native Agitator’; P. ka I. Seme, ‘Ku Mhleli we “Langa”’, Ilanga, 25 August 1916; with thanks to Sifiso Ndlovu.

175 ‘Doing Botha’s Business’, Sunday Times, 7 July 1918 on Abantu-Batho, 4 July 1918. The Sunday Times (‘Natives Say “No Strike”’, 20 June 1918) had earlier published in translation Msane’s leaflet.

176 ‘Another Mass Meeting at Vrededorp’, Abantu-Batho, 11 July 1918.

177 ‘New Year’, Abantu-Batho, 1 January 1920, GNLB 320, 301/19/72; Christison, ‘African Jerusalem’: 784. I thank Grant Christison for showing me Msane’s estate papers: he died 6 October 1919, left an estate worth £853, and his son was Herbert Nuttall Vuma Msane (NASA, Pretoria, Master of the Supreme Court (MHG) 42409).

178 Couzens, ‘Robert Grendon’: 54, 77–78; T. Couzens, ‘“The New African”: Herbert Dhlomo and Black South African Literature in English 1857–1956’, PhD, University of the Witwatersrand, 1980, 172, 193–94, 200–12.

179 Christison, ‘African Jerusalem’: 505, and chapter 5 in this volume.

180 Cooke to SNA, 16 February 1916, DNL 1329/14 D48, ‘Anglo German War: Native Newspapers: Abantu Batho’; Star, 9 June 1916: my thanks to Grant Christison for this observation.

181 Ilanga, 14 July 1916.

182 The first Congress mentions him as editor along with Mochochonono of M. N. Monyakoane, Naledi ea Lesotho of E. N. Monyakoane and Plaatje’s Tsala (Leselinyana, 25 January 1912).

183 Skota, The African Who’s Who: 80: Verwey, New Dictionary: 193–95; neither source is totally reliable.

184 Ilanga, 1 September 1916; Christison, ‘African Jerusalem’: 791, noting R. W. Msimang’s role either over a lawsuit Msane and Grendon brought against Abantu-Batho, settled out of court, or the merger.

185 ‘Summary of Statements … by the South African Delegation’, African Telegraph, May 1919: 226; ‘The Prime Minister and South African Native Deputation’, African Telegraph, December 1919: 298.

186 Skota, The African Who’s Who: 114; ‘Report … of the Annual Conference of the ANC January 4–5 1926’ and ‘Report … of the Annual Conference of the ANC’, Umteteli wa Bantu (hereafter Umteteli), 3 May 1930, in Karis and Carter, From Protest to Challenge, vol. 1: 299, 310; P. la Hausse de Lalouvière, Restless Identities: Signatures of Nationalism, Zulu Ethnicity and History in the Lives of Petros Lamula (c.1881–1948) and Lymon Maling (1889–c.1936) (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 2000): 93; ‘Izindatyana NgeZinto naBantu’, Ilanga, 9 October 1914; ‘Ezakwa Zulu’, Ilanga, 12 March 1915, repr. from Abantu-Batho.

187 Christian Express, 1 April 1907; ‘eTembize’ to Ilanga, 8 May 1908. On Msane and the Zulu National Association and Seme’s Native Landowners’ Association, see La Hausse de Lalouvière, ‘Death Is Not the End’: 268.

188 ‘Transvaal Native Council’, Ilanga, 11 June 1915; letter of D. Letanka and H. Msane with resolution, 11 December 1916, on letterhead with office-bearers, NTS 7204 17/326.

189 ‘Indaba yase Pitoli’, Ilanga, 31 May 1916; ‘Umhlangano Omkulu ka Congress’, Ilanga, 2 June 1916; ‘Umhlangano Omkulu wezindaba eJozi’, Ilanga, 15 December 1916; H. Msane, ‘The Modern Movement’, International, 21 July 1916; ‘Nge Pasi’, Abantu-Batho, c. April 1919, in Ilanga, 25 April 1919.

190 H. S. Msimang in Abantu-Batho 5, 18 December 1913; H. S. Msimang, ‘The Natives Land Act and Its New Phase’, Ilanga, 15 October 1915, cited in R. Grendon, ‘Thou Art the Man’, letters to Ilanga 5, 19 November 1915; H. S. Msimang, ‘Mr Msane and Native Congress’, Ilanga, 24 March 1916; see also Christison’s chapter in this volume.

191 Messenger-Moromioa: see H. S. Msimang, ‘Autobiography’, Alan Paton Centre and Struggle Archives, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, John Aitchison Papers, PC 14/1/1/1-3: 12a.

192 Skota, The African Yearly Register: 257; Skota, The African Who’s Who: 97; see also Couzens, ‘“The New African”’: 2. His father, Boyce Skota, had been a subscriber to Izwi Labantu and led a delegation on African women’s rights; see B. Skota, ‘The Curfew Regulations’, Tsala, 27 Phato (August) 1910.

193 ‘Isaziso Esibukali’, Umteteli, 11 February 1922; society notes in Imvo, 8 August 1922.

194 As claimed by T. Couzens, ‘A Short History of “The World” (and Other Black South African newspapers)’, African Studies seminar paper, University of the Witwatersrand, June 1976: 23.

195 R. T. Kawa, ‘Oziroxisileyo’, Imvo, 8 October 1912.

196 Skota, The African Who’s Who: 110. See also the entry on Dunjwa in Verwey, New Dictionary.

197 ‘Izindatshana NgeZinto naBantu’, Ilanga, 10 May 1918, drawing from Abantu-Batho.

198 ‘Itlanganiso ye Pasi e Nxekwebe’, Imvo, 2 June 1889; ‘Land Bills e Kapa’, Tsala, 14 June 1913; ‘Transvaal Native Congress’, Abantu-Batho, 15 May 1919, trans. in NTS 7204 17/326. In 1921 he was principal of the Abantu National Academy (‘Ezase Nancefield’, Umteteli, 13 August 1921).

199 ‘Labour Recruitment’, Umteteli, 30 July 1921.

200 A. W. G. Champion, ‘U-Mhlata’Mnyama’, 2 October 1930; ‘Christian Ministers of Religion and My Exile’, 9 April 1931; ‘The Story of My Exile’, 16 April, 25 June 1931; ‘You May Not See Us Alive Again’, 7 May 1931; letter 4 December 1930, ‘Native Unrest again in Natal’, 30 April 1931; ‘Umuntu kafi Apele’, 11 June 1931; ‘A Change of System’ and ‘Heroes of Trade Unionism in S. Africa’, 7 May 1931; all in Abantu-Batho. See also the Conclusion, this volume, and Limb, The ANC’s Early Years: 463–64.

201 R. Mdima and A. W. G. Champion, ‘Igatya leNatal Native Congress eGoli elizwisa uBantu-Batho …’, Ilanga, 23 May 1919. He was NNC Transvaal vice-president (A. W. G. Champion, ‘Intelakabili eGoli’, Ilanga, 2 May 1919).

202 Champion, The Views of Mahlathi: 56

203 Not to be confused (as so many have) with his uncle, Isaiah Budlwana Bud-M’belle; our thanks to Chris Lowe for unravelling this confusion. T. Couzens, ‘Pseudonyms in Black South African Writing, 1920–50’, Research in African Literatures 6(2), 1975: 226, drawing on an interview, suggests ‘Horatio’ used the pseudonym ‘Enquirer’, but this may well have been his uncle.

204 ‘Lovedale News’, Christian Express, 1 March 1906; ‘Kimberley’, Tsala, 6 August 1910; ‘Pass Law Resisters, Native Case Stated’, Star, 1 April, 1919; D. D. T. J[abavu] in Imvo, 22 February 1916; H. Bud-M’belle, ‘From the Native Standpoint’, International, 16 March 1917.

205 See leaflet of 20 June 1918 and ‘The Workers Indaba’, trans. from Abantu-Batho, c. June 1918, in NASA, Pretoria, Department of Justice (hereafter JUS) 3/527/17.

206 D. Herdeck, African Authors (Washington: Black Orpheus Press, 1973): 359.

207 ‘Native Teachers Association (Eastern Branch of T.N.T.A.)’, Abantu-Batho, 26 October 1916, Jane Cobden Unwin Papers, University of Bristol Library, Special Collections, GB 3 DM 851 (my thanks to Brian Willan for this document); Skota, The African Who’s Who: 54–56.

208 A. S. Gérard, African Language Literatures (Harlow: Longman, 1981): 221.

209 Karis and Carter, From Protest to Challenge, vol. 4: 68 claim Makgatho ‘helped produce Abantu-Batho’.

210 Couzens, ‘The Struggle to Be Independent’.

211 Unpublished biography by S. M. Molema (which is forthcoming by Sekepe Matjila). The Times erred when its obituary had him as editor of Abantu-Batho (‘Mr. Solomon Plaatje’, 28 July 1932).

212 Abantu-Batho, 15 April 1915, in SwNA, RCS 23/1915; Abantu-Batho, 26 January 1928.

213 Roux, ‘The Bantu Press’, claims black editors refused ‘to be frank about circulation’ and total circulation of all black papers was 50,000–100,000, but each copy was read by three to four people.

214 Letterhead, Kunene to DNL, 16 July 1914, DNL 362/14 D80; ‘Our Paper’, Abantu-Batho, 11 June 1931.

215 ‘Monogamy versus Polygamy’, Christian Express, 1 March 1913: 35.

216 C. S. Mabaso to De Beers Consolidated Mines, Kimberley, 14 February 1914, in De Beers Archives, Kimberley, General Secretary’s Correspondence. Mabaso noted that the governing body recently had been reorganised into a limited liability company. My thanks to Brian Willan for showing me this letter.

217 Abantu-Batho, February–March 1920; and on the mastheads of 4 July 1918 and 26 January 1928.

218 C. S. Mabaso to Government Printer, 17 March 1922, DNL 144/13 D205.

219 M. Mutloatse, Umhlaba Wethu: A Historical Indictment (Johannesburg: Skotaville, 1989): 33.

220 Couzens, ‘The Struggle to Be Independent’: 44–45 cites circulation from Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Press (Pretoria, 1962), annex 784 as Bantu World 16,000 (1945); Ilanga 13,000 (1945); Bantu World in 1933 claimed 40,000. J. G. Coka, ‘The South African Press World’, Capital Plaindealer (Topeka), 11 October 1936, put the circulation of Bantu World at 12,000, Umteteli at 7,000 and Umsebenzi at 6,000.

221 One of them was Lymon Maling (La Hausse de Lalouvière, Restless Identities: 217, 222, citing ‘The Circulation of Abantu-Batho’, Wits Historical Papers, Skota Papers, A1618 (this now appears to be misplaced)). Msimang felt 1,000 copies of a paper would then have cost £17 in Bloemfontein (‘Autobiography’, Alan Paton Centre and Struggle Archives, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, John Aitchison Papers, PC 14/1/1/1-3: 12a).

222 J. Magagula, ‘Inkanyiso yase Natal as an Outlet of Political Opinion in Natal, 1889–1896’, BA (Hons) mini-dissertation, University of Natal, 1996: 21.

223 Willan, Sol Plaatje: 109, 125.

224 T. Couzens, ‘Widening Horizons of African Literature, 1870–1900’, in L. White and T. Couzens (eds), Literature and Society in South Africa (Harlow: Longman, 1984): 74.

225 G. Shaw, The Cape Times: An Informal History (Cape Town: David Philip, 1999): 11.

226 Rosenthal, Bantu Journalism: 13; Friedgut, ‘The Non-European Press’; Roux, Time Longer than Rope: 361, ‘The Bantu Press and Race Relations’, Race Relations 2(1), 1934: 129–30.

227 M. Lyons, ‘New Readers in the Nineteenth Century: Women, Children, Workers’, in G. Cavallo and R. Chartier (eds), A History of Reading in the West (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999): 343.

228 Switzer, ‘Moderation and Militancy’: 39.

229 J. Lonsdale, ‘“Listen while I Read”: Patriotic Christianity among the Young Gikuyu’, in T. Falola (ed.), Christianity and Social Change in Africa: Essays in Honor of J. D. Y. Peel (Durham: Carolina Academic Press, 2005): 571–72.

230 S. T. Plaatje, Sechuana Proverbs with Literal Translations and Their European Equivalents, in Selected Writings, ed. B. Willan (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 1996): 216.

231 C. L. Harries, Memo, 14 May 1919, University of Cape Town Library, G. Lestrade Papers BC255 K.1.8. I thank Brian Willan for sharing this document.

232 ‘The Leadership of Educated Men’, Abantu-Batho, c. March 1914, repr. in The Colonial and Provincial Reporter (Freetown), 2 May 1914. One paragraph was also published in ‘Native Papers and Missionaries’, Tsala ea Batho, 21 March 21, 1914. Skota in the mid-1920s received the Garvey press and many letters from West Africa (Benson Papers, SOAS, Mss. 348942/1, ‘Skota’: 4).

233 ‘Abantu-Batho Newspaper: Local Agencies Cape Colony’, Abantu-Batho, 11 July 1918; advertisement in Abantu-Batho, 14 June 1923: the paper’s office was then still based at 75a Auret St., Jeppes.

234 Switzer, The Black Press: 24.

235 See Limb, The ANC’s Early Years: 156.

236 Sub Native Commissioner (NC) Nylstroom to NC Nylstroom, 26 February 1919, NTS 7204 17/326.

237 Reports in Abantu-Batho, 20 December 1917, JUS 3/527/17.

238 J. J. Kekana, ‘Pitso ea Morena Dower’, Abantu-Batho, 20 December 1917, JUS 3/527/17.

239 A. Manson (ed.), An Oral History of the Life of William Barney Ngakane (Johannesburg: South African Institute of Race Relations, 1982): 33, 38.

240 See the issue of 4 July 1918, DNL 1441 D205. After 1929 the symbol did not reappear.

241 ‘The White Servants Have Got Their Money’, Abantu-Batho, 19 February 1920, reproduced in CID to SAP, 20 February 1920, JUS 3/127/20.

242 ‘Ama Almanaka ka 1916’ and ‘Li Almanaka tsa 1916’, Abantu-Batho, 20 January 1916, Coryndon Papers, Rhodes House Library, Mss. Afr. s.633, box 10/1; ‘I Almanaka ngenteto Bantu’, Imvo, 11 May 1915.

243 D. D. T. J[abavu], ‘Kwelipezulu’, Imvo 1, 1 February 1916. By 1918 it was still being sold for 7d by post. For rendering this text and data on Reuben Davies, my thanks to Chris Lowe.

244 ‘IAlmanaka ka “Bantu-Batho”’, Ilanga, 1 February 1918. Grant Christison kindly provided a translation. These portraits helped identify images in the Skota Papers as being from the Almanac.

245 ‘Izindatyana NgeZinto naBantu’, Ilanga, 17 February 1922; ‘Abantu-Batho’, Imvo, 21 February 1922. Imvo (18 March 1913, 10 February 1920) also had an almanac: a Zulu almanac, and commercial and religious ones (such as in Morija) were circulated, but almanacs have received little scholarly attention.

246 D. D. T. Jabavu, ‘Are the Bantu Inherently Inefficient?’, Christian Express, 2 May 1921: 79.

247 Cleopas Kunene to Director Native Labour, 4 June 1915, DNL 144/13 D205.

248 See ‘I-Concert enkulu eGoli’, Ilanga, 21 November 1921.

249 ‘Abnatu[sic]-Batho Ltd’, Ilanga, 23 April 1915, repr. from Abantu-Batho, reports on Letanka, Mabaso and Nkosi and the company, subscribers and agents.

250 Grievances of Natives of South Africa: An Appeal to the People of England against Natives Land Act, 1913 (Sophia-Town: ‘Abantu-Batho Ltd.’, 1914), National Archives UK, CO 551/67, ‘Natives Land Act’.

251 R. W. Msimang, Natives Land Act 1913: Specific Cases of Evictions and Hardships, etc. (Cape Town: Friends of South African Library, 1996), colophon.

252 ‘Cleopas Kunene Sophiatown: Complaint against Pass Office Johannesburg, re Registration of Labourer’, [on Abantu-Batho letterhead, dated 12 January 1915, in DNL 15/15 D80].

253 Skota, The African Who’s Who: 18. Cobley, Class and Consciousness: 176 n. 48 notes Merafe as ‘foreman and machine-man in charge of the printing press in Sophiatown’.

254 A. D. Dodd, Native Vocational Training: A Study of Conditions in South Africa, 1652–1936 (Lovedale: Lovedale Press, 1938): 97, citing Lovedale Students’ Records, 4405.

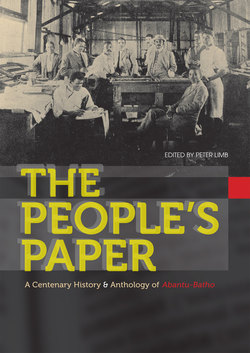

255 Benson Papers, SOAS, Mss. 348942/1, ‘Skota’: 3–4.

256 Cf., for instance, what we know of the inner workings of The Rand Daily Mail (R. Gibson, Final Deadline: The Last Days of the Rand Daily Mail (Cape Town: David Philip, 2007)).

257 Gerhart Photographs, Wits Historical Papers, A2794/16C.1-3. This appears incorrectly attributed by the History Workshop, who wrote on the back ‘Bantu World-printing works and staff, 1920s’, which is clearly an error, as Bantu World only began in 1932; ‘Sale in Execution’, Rand Daily Mail, 24 March 1916. My thanks to Chris Lowe and Michele Pickover for help on this matter.

258 DNL 1329/14 D48, undated draft telegram by M. Carroll. Cf. SNA to DNL, 2 May 1919, DNL 144/13 D205, attaching copy of Articles of Association of Abantu-Batho and list of proprietary shareholders.

259 Cf. A. Dick, ‘Book History, Library History and South Africa’s Reading Culture’, South African Historical Journal 55, 2006: 33–45, but with little attention to black newspapers.

260 M. Lyons, Readers and Society in Nineteenth-century France: Workers, Women, Peasants (New York: Palgrave, 2001): 156, 160–61.

261 S. Mkhonza, ‘Newspapers in Indigenous Languages and Democracy in South Africa: A Socio-historical Perspective’, paper presented to the Language, Creative Arts and Media conference, University of Pretoria, 22 June, 2008: 11, 14.

262 J. Seidman, Red on Black: Story of the South African Poster Movement (Johannesburg: STE, 2007): 23.

263 On the meaning of the ‘new African’ see Couzens, ‘The New African’, especially 271 ff.