Читать книгу The People’s Paper - Christopher Lowe - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

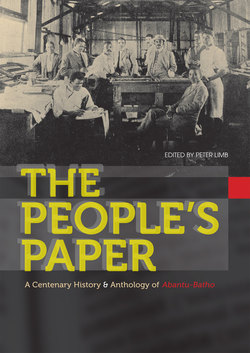

A Centenary History of Abantu-Batho, the People’s Paper ABANTU-BATHO: A VERY SHORT INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеThe 2012 centenary of the African National Congress (ANC) is also that of the closely allied newspaper, Abantu-Batho (The People). This little-studied weekly was established in October 1912 by the convener of the ANC, Pixley ka Isaka Seme, with financial assistance from the Queen Regent of Swaziland, Labotsibeni. It attracted as editors and journalists some of the best of a rising company of African intellectuals, political figures and literati such as Cleopas Kunene, Saul Msane, Richard Victor Selope Thema, T. D. Mweli Skota, Robert Grendon, S. E. K. Mqhayi and Nontsizi Mgqwetho. In its pages important themes of the day, from the pass laws, Land Act and the World War to strikes and socialism, the founding of Fort Hare, the rights of black women and Garveyism were articulated, just as mundane events such as football matches, marriages and church gatherings were reported. It was also a forum for letters and literary contributions, some of the highest calibre, others of a plebeian bluntness.

A dynamic black press had already been established in some cities and towns by 1912. The ability to spread news in a printed format had once been a virtual monopoly of the colonial state or the missions, but the rise of a black-owned and -edited press challenged this, just as the spread of new communications and news agencies opened up space to share ideas more freely. In the latter-half of the nineteenth century, a nascent African intelligentsia developed letter-writing networks1 and then, having few publication outlets, created their own regional newspapers such as Imvo Zabantsundu (Native Opinion, 1884–) of J. T. Jabavu, Izwi Labantu (Voice of the People, 1897–1909) of A. K. Soga, Koranta ea Becoana (Bechuana Gazette, 1901–08) and Tsala ea Batho (The People’s Friend, 1910–15) of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje, and Ilanga lase Natal (Natal Sun, 1903–) of John Langalibalele Dube, plus several weeklies printed across the border in Basutoland (now Lesotho).2 The editorial politics of these weeklies was always strictly within constitutional limits, but in favour of extending black rights. Like Abantu-Batho, their circulation and readership (see below) were modest, but their impact on emergent political bodies was large. Their relationship to Abantu-Batho was sometimes stiff – after all, they were commercial (and often political) rivals, sometimes more intimate, but often they swapped or reproduced one another’s stories, a practice that has greatly assisted the realisation of this book.

In the Transvaal this press was slower to emerge in the face of harsh anti-black laws, but in the first decade after the South African War, pioneer black newspapers helped inculcate reading habits and impart journalistic skills, thus starting to create an audience and forge a foundation on which Abantu-Batho could soon build. In Pietersburg (now Polokwane), the short-lived Leihlo la Babathso (Native Eye, 1903–08) of Simon Phamotse and Levi Khomo gave voice to the Transvaal Native Vigilance Association.3 Then from Johannesburg in 1910 came the weeklies Motsoalle (Friend, later Moromioa, or Messenger) of Daniel Simon Letanka in Setswana/Sepedi and Umlomo wa Bantu-Molomo oa Batho (People’s Mouthpiece) of Levi Thomas Mvabaza with Saul Msane in English/isiXhosa/ Sesotho. Both broadsheets would merge (in 1912 and 1916, respectively) in a new paper tied to the Transvaal Native Congress (TNC) and South African Native National Congress (SANNC, ANC from 1923), whose founding, and that of its public voice, Abantu-Batho, trumpeted a rival legitimacy.

Africans soon made good use of these papers to communicate and to organise politically, for, while commercial ventures and moderate in tone, they had to operate in a society that discriminated harshly against black people.4 A new political culture primarily articulated via the black press and public meetings was emerging.5

All these members of the black Fourth Estate remained under close neocolonial scrutiny. As with the subaltern press in other colonial situations, state censors would closely monitor Abantu-Batho6 and government officials hauled managing editor Seme before them to explain stridently anti-imperial wartime editorials.7 Still, as long as it did not become too radical, the state could use the black press for conveying official notices and managing unrest. In 1905 the South African Native Affairs Commission saw it as ‘an infant press’, yet ‘fairly accurate in tracing the course of passing events and useful in extending the range of Native information’.8 Yet, given its physical existence on the Rand, in the centre of the country’s political storms, and its centrality to Congress and vernacular discourses – at the very ‘point of intersection between political intelligence and indigenous knowledge [where] colonial rule was at its most vulnerable’9 – there was every chance it would become more radical – and it did.

The idea of a new, multilingual newspaper with a truly national focus was raised, probably by Seme, at a meeting in Johannesburg in 1911 connected with the South African Native Convention, which led to the January 1912 launch of the SANNC.10 That Abantu-Batho from its launch later that year to its end in 1931 would be adopted at various times as an organ of Congress, and would articulate its policies and promote its campaigns flowed from the fact that the movement’s founder, Seme, had also founded the paper. The 1919 constitution of the TNC registers Abantu-Batho as its organ and in the late 1920s it became the national ANC mouthpiece.

Yet it was much more than a mere party ‘organ’. The very title Abantu-Batho – The People, from ‘ntu’ (Nguni) and ‘batho’ (Sesotho-Setswana) – spoke meaningfully to readers in a wide range of African languages11 – it published simultaneously and in some depth in Sesotho, isiXhosa, and isiZulu, with some Setswana, as well as in English – and clearly to the vision of ANC founders for unity and nation building.12 The term ‘people’ (like ‘nation’), invokes fraught and contested concepts used and abused by populists of many persuasions (see below). There were, of course, many ‘peoples’, just as one can also characterise other weeklies, such as Imvo and Ilanga, as ‘people’s papers’. Neither do we suggest that if some other newspapers were not official organs of Congress, then they could not represent certain peoples, or indeed the collective ‘people’. However, Abantu-Batho claimed a wider mantle, a national focus (even if it sometimes fell short of this aim), and the term had a ‘naming, identifying’13 role that sought to recapture African dignity lost under colonialism. It was a call to arms for editors to vigorously defend the causes espoused by ‘the people’, a mission executed in editorials (and associated campaigns) on land, civic and human rights. Looked at retrospectively, it was this sort of vigorous, popular approach epitomised by Abantu-Batho that would eventually mobilise wide sections of ‘the people’ to overcome colonialism and apartheid.

Over the 19 years of its existence this paper played an important role in influencing and reflecting African political thought and intellectual life in South Africa and beyond. Its history is a fascinating and complex story, a remarkable window into social and intellectual life and political culture in the early twentieth century. Here too we see the triumphs and failures of its own editors, together with political leaders, as African nationalist networks were forged and tempered, as moderates and radicals alike absorbed, adapted and re-cast new ideas and forms of discourse, grappled with issues of tolerance and democracy, and networked across different social classes and peoples to try to forge new social, ethnic, and political identities and viable social forces. If the relatively narrow social base (and material resources) of the newspaper, like that of the SANNC, meant that it never entirely or consistently lived up to its populist ambitions in the period,14 then it accomplished a great deal in setting the pace for and broadening the focus of the black press.

The weekly went through various phases, some more radical and others more moderate, and had a wide range of editors (see further below) before it ceased publication in July 1931. This introduction and the first pair of chapters outline the broad contours and contexts of Abantu-Batho’s hitherto hidden rich history, historiography, structure and thematic content. These themes are then taken up in detail by the book’s contributors. The concluding chapter assesses the legacy of the ‘People’s Paper’.