Читать книгу Peace, Love & Petrol Bombs - D. D. Johnston - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

The way I tell it, I almost die. The train has a metal cow catcher and it’s mushrooming steam and it’s blasting a fuck-off-angry klaxon and I’m on the tracks and at the last second—when the light’s gone bright, when my life’s flashed before me—I am pulled to safety.

She says it wasn’t like that. She says the train was hardly in view, that it was almost stationary, that we could have sat down and eaten a picnic before it reached us. I like to think she’s too modest. I know that she was wrapped in black clothes—black hoodie, black combats—shouting “Allez quoi!” through a black bandana. “Come on! Putain! Viens!” A hundred metres away, beyond the police vans and motorcycles, the black bloc trickled out of view, leaving the pavement rubbled with cobblestones. I remember that she ran into the woodland that banked the road and I followed. She gestured for silence, as if the crack of twigs could be heard above the rattling helicopter, the sirens, the echoing detonations. “Merde. Sprechen sie Deutsch?”

“What?”

“Italiano?”

“No, Scottish.”

“Scottish? I tell you to fuckeeng move! Now we are alone to be beaten and raped.” She crouched in a rhododendron bush, still wearing her swimming goggles. “Stupide.”

“Sorry,” I said, considering taking my chances with the police. “You want a cigarette?”

“I have my own. Do you have the fire?” The lighter shook in my hand as I lit her cigarette. When I pulled down my bandanna, she laughed. “You are white as a ghost!”

“We don’t get much sun in Scotland.”

“You are how old, Petit Fantôme?”

“Twenty.”

“Non! I thought you are fifteen! Anarchiste?”

“Kind of.”

She pulled her swimming goggles over her head, and her brown eyes spread out like melted chocolate. When she removed her hat, her fringe spiked with sweat. The rest of her hair was clipper short. On her left cheekbone, an inch-long scar curved neat and white, like the scars they paint on the cheeks of Action Men and GI Joes. She smiled and blinked and stuffed her gear into her backpack. All these things were heroic.

After two minutes, she said “On y va” and crawled through the bush, tip-toeing onto the road. “Bon. We find the comrades. We follow the smoke and the helicopter, yes?”

And I thought: We stoned the police; we set them on fire; the people they catch are fucked. So I shrugged as nonchalantly as I could and pointed up the street. “You know, I was just after getting something to eat?”

She looked at me and laughed. “You want to stop for lunch? You are sure you are not from France?”

Prague, September 2000. The day we charged the World Bank Summit, crashing through crowd barriers, smashing folds in police lines. The police dropped their shields and beat flames from their uniforms. They fired more teargas and the crowd pushed back then forward and a water-cannon traversed the road, tumbling protesters down the slope. I ran downhill, out of the gas, to an intersection below the bridge, where the jet from the water cannon trickled between the cobblestones, and I stood, gasping, hands on knees, looking back at the mist of gas and smoke. I had lost Spocky.

There was no fighting at the intersection. People were juggling and twirling ribbons and playing diabolo. When police reinforcements arrived with two armoured personnel carriers, a man in a woollen poncho sat cross-legged on the road; a woman in a raincoat threw flowers. The police formed a new line, thirty metres from the Čiklova intersection, and then we built a barricade. We piled logs and branches, street signs, an office chair. A Polish skinhead tried to light it. I helped fill wheelie bins with cobblestones.

Then the police advanced and you could hear stones hitting tanks and the hippies chanting “No violence—No violence—No violence.” There was a man lying on the pavement, drooling blood onto his vest. A German punk bowled a bottle across the barricade. “Hey! Provocateur!” shouted an Englishman in a blue pac-a-mac.

“No violence—No violence—No violence.”

“Fuck you! Fuck da poleez!”

“People fucking live here, yeah?”

“If the World Bank come to my town,” said the injured guy, spraying a speech bubble of blood around every syllable, “you burn my grandmother’s house!”

“Opá,” said his friend, pointing into the gas. “Batsi.” The explosions were louder and the air was thicker and it had become harder to breathe. The Englishman in the blue pac-a-mac stood up; then the circle of pacifists stood up; then the medics stood up. Soon everyone was standing, wondering why everyone was standing. Then people were jogging past us, red eyed and gasping—Czech syndicalists in construction helmets, German anti-fascists wearing balaclavas. They bottled into the yellow underpass below the railway line, and hundreds tried to squeeze behind them. Then the police emerged from the fog, weighed down by armour. Somebody shouted “Come on!” but I was sprinting across the grass verge, by the railway fence. Too late I saw the police emerge from the trees, running down the hill in a line.

The cop who hit me, who chased me into the path of the train, was splashed with white paint and had lost his truncheon. He crashed me into the railway fence, and as I held onto it and tried to climb, he punched me again. I was scrabbling my feet, tearing my hands on the wire, and he was behind me, wheezing through his gas mask. The fence collapsed under my weight and threw me hands first onto the railway line. I pushed off the ground, took one step, two steps, stumbled, tripped and—

In Bar Neviditelný Hněv, old men stood up, gesticulating at the street, arguing as they watched the riots on TV. Otherwise, the room was empty. We sat at a table in the corner, and she fidgeted with the salt shaker, making L-shaped knight moves across the red and white checked tablecloth. “I’m Wayne, by the way.”

“You know who made the first cup of tea in Prague?”

“The first cup of tea?”

“Michael Bakunin.”

“Aye ?”

“Oui. He ask for tea in a restaurant. They do not know, so he go to the kitchen, make the tea.”

“He carried tea about with him?”

The barman shuffled to our table and flicked the top page over the edge of his notepad. By 2003, when the G8 met in Evian, the police had learned to commandeer whole towns, so you couldn’t even get a bottle of water; in Prague, however, the streets were cobbled, the police force had the crowd control skills of a student P.E. teacher, and the restaurants were so cheap that we almost lived like the delegates. Sure, the low cost of living didn’t stop Germans in Exploited t-shirts from scrounging Koruna on every street corner, but nobody cared: you could eat a good meal, wash it down with Pilsener, and still have change to pay off the German anti-fascists. “Eh, can I have the fish. And a beer, please. Big,” I said, gesturing something the size of a bucket.

He nodded and scribbled.

“Jeden Staropramen prosim,” she said, “et… brambory?”

“Brambory? Huh… hranolky? French fry?”

“Ano, ano.”

“Dobrý,” he said, accepting the menus.

“Dekuje”—she pronounced it day-kwee.

“How d’you say thanks?”

“You eat fish?”

“I’ve been saying ‘Deck-you-jay’.”

“Fuckeeng idiot!”

“How many languages d’you speak?”

“You eat fish?”

“Aye—what’s wrong with the fish? You don’t like fish?”

“I am vegan.”

“Right,” I said, unsure how to deal with this. “You ever like… I dinnae ken, like really miss just ordering a steak or something?”

“Non. You know what I miss, what I really fuckeeng miss? I miss, maybe, just once, to eat dinner with no imbécile tell me I want some meat.”

“Sorry. What made you become vegan?”

“Now you want to start an argument because you feel insecure. Because in there,” she pushed her finger against my forehead, “you do not really understand why you think it is wrong to kick a dog, when you think it is okay to eat a cow.”

“No, I—”

“You want to tell me how much I miss meat, yes?”

“No.”

“You want to pick what ever fuckeeng badly cooked shit is on your plate and you want to put it in my face, yes?”

“No!”

“And then I want to be polite so… je m’en fous: ‘It look nice,’ I say. But this will only encourage you. And next you will tell me it is un-natural to be vegan, yes?” I laughed because it was true. “And maybe I really do not want to argue. So I shrug—peutêtre—is opinion. Then you will keep on and fuckeeng on. Until eventually I say, ‘But people did not eat dairy until the last few thousand year.’ Then you will be very angry, look at me and say, ‘This is what I cannot stand about you fuckeeng vegans. You have always to shove your view down everyone else’s mouth.’”

I laughed. “No, I dinnae think any of that.”

She smiled and lit a cigarette like a movie star.

She told me King Wenceslas was never a king. She told me Wenceslas Square is one of those places history won’t leave alone. Think about the dates, she said. It kicked off here in 1848; in 1948, it witnessed the Communist coup. In 1918, crowds celebrated an independent Czechoslovakia; in 1968, they returned to fight the Tankies. The Nazis invaded in 1939—fifty years later, where did the people gather during the Velvet Revolution? Here. Night after night, until the Jakeš leadership resigned, and Havel and Dubček stood together, just up there. And at the top of the square, Národní Muzeum, shot at by Soviet troops, its steps where Jan Palach set fire to himself: a box seat on the century.

We started from where we had last seen the black bloc and followed the graffiti, the broken windows and smouldering barricades, until the trail faded and the streets we walked through had a quiet normality. We passed a middle-aged couple in matching Jubilee 2000 anti-debt t-shirts, and a group of Italian disobidienti wearing white boiler suits stuffed with padding. We followed the tramlines back to Námestí Míru but found the square empty except for the International Socialist contingent, their placards drooping as they traipsed in the shadow of the charcoal-coloured church. A helicopter swung over the church and a black kitten ran across the tramlines, through the trampled flower beds, where it stopped, looking up at us with a pet-me meow. “Le chat,” she said, dropping onto one knee and extending a finger. The cat padded forward, sniffed her finger, and then rubbed the side of its face against the back of her hand. It rolled on the ground so she could tickle its belly and then, suddenly bored with this, stood up and stretched, arching its back before bounding across the square scattering pigeons. As we walked on, she said, “When I am sixteen, I buy a cat.”

“Aye ?”

“I was a cleaner. In Paris. This was 1993, and I live in a tower block, on floor eleven. One day my friend telephone me and ask do I want a cat. In my appartement? I do not think so. But then she tell me that her brother want to drown the cat, so, okay. When I get there the cat is in a bag with some stones. It was very small, and beautiful, with big blue eyes and silly fur, and the brother of my friend say it cost one-hundred-Francs. I say, fuck off—you want to drown this cat! He say, there were six of these cats and he sell five and nobody want this cat. He say—vraiment—he say, it is not fair on his other customer if he give me the cat for free. I say, ‘Ta mere elle suce des ours!’ And he shrug and drop the cat back in the bag. But its eyes! Putain, I could not leave it. So I buy this stupide cat. And all the way to the appartement, it... I do not know in English, the happy noise of the cat?”

“Purring ?”

“How do you say?”

“Purring, it purred.”

“Yes, it purred. It was very thin beneath the fur. I carry it up eleven floor of stairs, and I say, ‘Ça va, ma petite chatte? Mignonne friponne.’ I knew nothing about cats except they like milk, so I pour it milk and then I go to sleep, very tired. And when I wake up, when I wake up, the stupide fuckeeng cat has piss on my floor.”

“So what did you do with it?”

She stopped to look at a church, circling it with her eyes. “You know why it is like this, this city? Emil Hácha surrender Tchècoslovaquie to the Nazis so these buildings would not be destroyed.” She heeled 360 degrees, put a cigarette to her mouth, and mimed for the lighter. “Why did you come here?”

“Why did I come to Prague?” I said, lighting her cigarette. “I was at a football match in Germany.”

“You have gone to Germany to watch a football match?”

“Aye. My mate Spocky said I should come here.”

“Why?”

“It was the UEFA Cup.”

“No, stupide, why does he say you are to come here?”

“You ken, for the demonstration and that.”

She started to walk again. “Spocky? You have a friend who is called Spocky?”

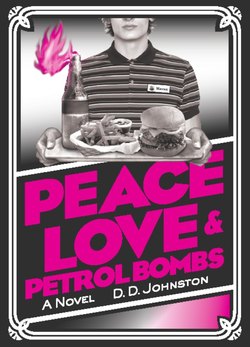

“It’s kind of like a nickname. We work together, in the fast food industry, Benny’s—”

“Benny’s Burgers?”

“We ken it’s a shite job, that’s why we’ve—”

“Lentement.”

“What?”

“Slow, slow.”

“Sorry. Ken means know.”

“I like your accent.”

“Aye? Barry means good. If you had a friend called Ken you could say ‘D’you ken Ken? He’s barry, eh? Radge means—’”

“You are working at Benny’s Burgers?”

“Aye. We’ve started this group, like a trade union.”

“Ah. This is in Scotland?”

“Aye.’

“Glasgow? Édimbourg?”

“Dundule. It’s kind of between the two.”

“Ah. And Spocky, he is also at the football match?” The way she asked these questions made my story sound like an absurd lie.

“No, he doesn’t like football. He came for this.” We passed a boutique with a jagged hole in its window and “NO WB” and “FUCK IMF” sprayed across its walls in red and black.

“And now he is where?”

“Who?”

“Your fuckeeng friend.”

“Oh, Spocky. I Dinnae ke—I don’t know. I lost him in the tear gas.”

“So maybe he is arrested?”

“I dinnae ken. I was looking for him when I met you.”

“Non—when you met me, you were asleep on the railway.” Then we reached Wenceslas Square and girls cobblestoned Mc-Donald’s and skinheads kicked the glass out of Deutsche Bank and local kids threw furniture out of KFC. It was there that she told me King Wenceslas was never a king, that history won’t leave Wenceslas Square alone; she was shouting above the applause of shattering glass. Then the police formed lines in front of the museum and burst the night with gas canisters and firecrackers. We ran forward throwing bottles and cobblestones, and somewhere in the back and forward, between our nervous advances and panicked retreats, I lost her in the crowd.